St. Andrew’s Methodist Church (West Side Institutional Synagogue)

120 West 76th Street

by Tom Miller

With the Upper West Side’s population exploding in 1879 and without a Methodist church to serve it, the Rev. W. S. Blake told a meeting of the New-York City Church Extension and Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church that “his people relied upon two things–Providence and the elevated railroads.” Providence came in the form of the stone St. Andrew’s Chapel at Nos. 123 and 125 West 71st Street in 1882. Within three years the congregation gained independence as St. Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church.

In the winter of 1888-89, a committee was formed to purchase real estate for a new, more substantial church. On March 2, 1889 the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that St. Andrew’s had purchased “a plot 130 x 102.2, on the south side of 76th street, between 9th and 10th avenues, for about $15,000 per lot.” The total cost for the seven 18.5-foot plots would equal $2.96 million today.

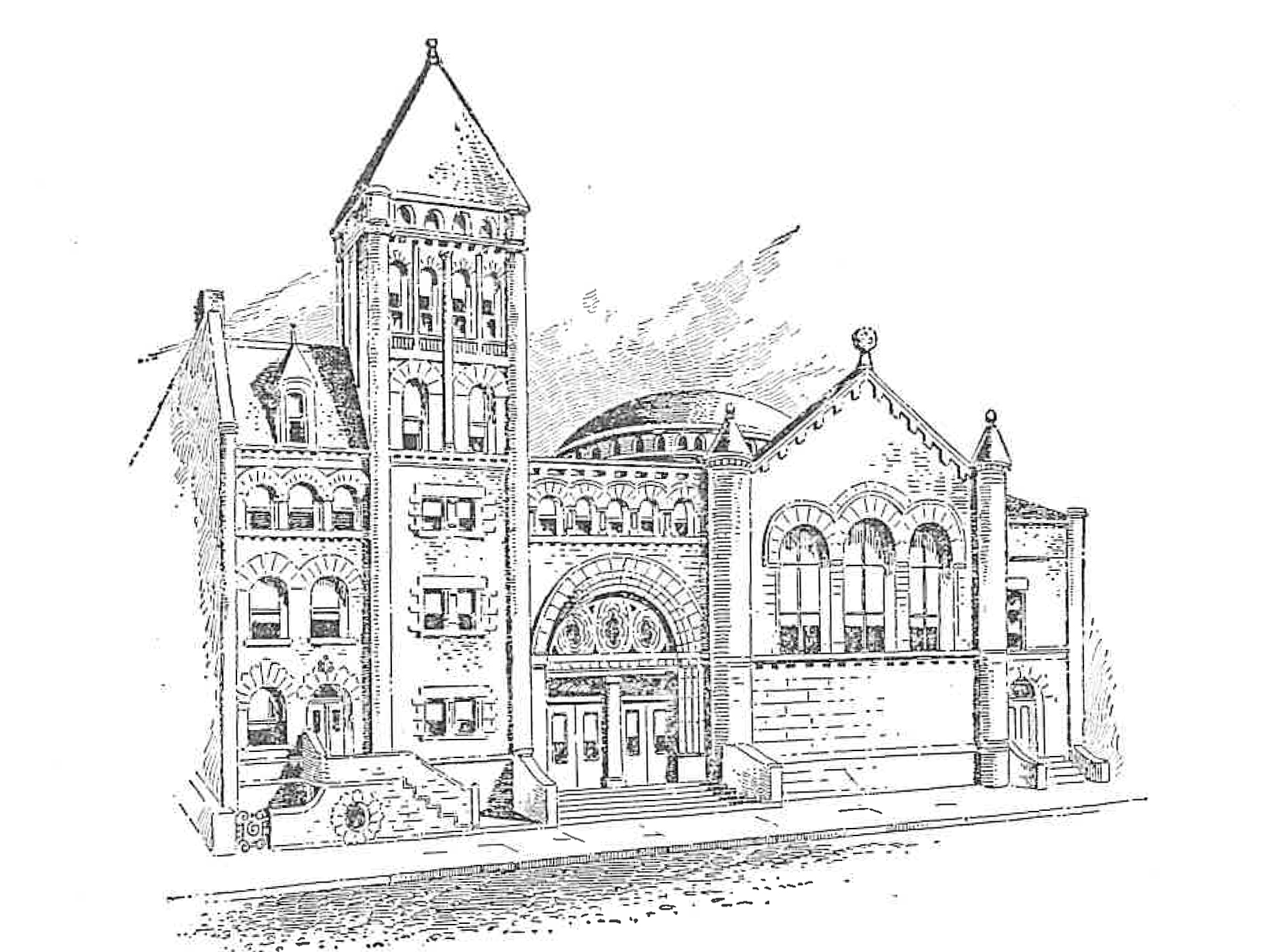

On May 27, 1890, the New-York Tribune reported that the pastor had commissioned J. C. Cady & Co., “the well-known architects of No. 111 Broadway,” to design a new church on the south side of West 76th Street. The newspaper promised “The church architecture of this city will be enriched in the course of the present year by an example of great beauty.” In fact, the firm had been at work on the designs for a full year, and offered water color renderings to the press in late 1889.

J. C. Cady & Co. worked in the Romanesque Revival style, making full use of contrasting materials, colors and textures. Rather than the visually-ponderous granite or brownstone expected in Romanesque Revival churches, the architects used limestone. The darker stone was used only for the trim, creating a much lighter appearance.

On April 20, 1889, the Record & Guide described the complex, saying the church proper would seat “about 800 people, exclusive of the galleries, which will not be built until they are required, probably a few years hence.” Congregants in the main auditorium sat below a 50-foot-wide dome perforated by stained glass windows.

The entrance doors sat within a large, medieval-style arch and stained glass transom. They opened into a 20-foot-wide vestibule “fitted up in oak, with a handsome ceiling and fire-place.” It separated the church from the 33-by-99 foot chapel, which would accommodate another 450 worshipers. Above the chapel, within the imposing bell tower, were the Sunday school rooms.

Dr. J. M. King, the pastor, would live in a handsome 18-foot-wide rectory, four stories tall, which carried on the Romanesque motif. The Record & Guide noted “All the buildings will be finished in massive oak and have steam heat and other improvements.”

The complex was completed in 1890 and fund raising to pay off the debt became a major focus. Nearly a decade later it was still going on. On December 6, 1899 the New-York Tribune reported “Edgar W. Williams will deliver a lecture on ‘My Experiences in Porto Rico,’ illustrated with stereopticon views, in St. Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church on Friday evening. The proceeds will be applied toward liquidating the church debt. Eighteen months ago $105,000 was raised for this purpose.”

In November 1901 the convention of the Woman’s Home Missionary Society was held here. Women came from around the country to discuss the conditions and progress of missions, schools and orphans’ homes. On November 9, for example, the New-York Tribune reported that “Four little girls from the De Peyster Home, at Tivoli, sang a hymn. The home is maintained by the society for orphan girls, and now has sixty-nine in its family.” That morning “There were several appeals for money for schools and homes for negroes, and these seemed to meet with peculiarly hearty and generous response.”

Rather than the visually-ponderous granite or brownstone expected in Romanesque Revival churches, the architects used limestone.

But the women who had no agenda more controversial than feeding and housing orphans got a surprise guest. Four days later the New-York Tribune reported that the Rev. Dr. James M. Buckley, editor of The Christian Advocate, “called during the morning session.” He challenged the group to consider two “crying evils”–“the growing disregard of the Sabbath and the enormous increase in the liquor traffic.” Buckley was on his way to Pittsburgh to meet with the missionary committee of the Methodist Episcopal Church. His arm-twisting was not subtle. “I feel that I shall be able to present these subjects more forcibly to my audience on Thursday evening if I am armed with a set of resolutions embodying the sentiments of this organization.”

The women complied, skillfully wording a resolution on liquor to fit with their own program. It said in part “that because the society has for its object the amelioration of the condition of destitute women and children…and because it believes that the liquor traffic is the greatest enemy to the home and to the upbuilding of Christ’s kingdom, the society pledged itself to advance in every way in its power the cause of temperance.”

Dr. James Oliver Wilson had joined the staff of St. Andrew’s in 1895. A firebrand of sorts, his sermons sometimes raised eyebrows. Such was the case on September 15, 1901 when, following the assassination of President William McKinley by Leon Czolgosz, his sermon dealt with the problem of American anarchists in general. And his solution was straight-forward–kill them.

He said in part “If we have not a law that will hang the anarchist who attempts to kill his victim–and that without any lengthy formality–we ought to have such a law, and will.” He deemed Czolgosz worse than either John Wilkes Booth or Judas Iscariot. “They were both hypocrites, but McKinley’s murderer was the worse…Judas was sorry his treachery was responsible for Christ’s crucifixion. Czolgosz is glad his bullet proved fatal. The Master once called Judas a devil. What would he call this monster in human form? May the law speedily put an end to him and all of his kind.”

It may have been his politically- and socially-charged sermons, or simply his own ambition that prompted the board to “take steps to dissolve the pastoral relations with the Rev. Dr. Wilson,” as worded by the New-York Tribune, the following June. A “leading New-York Methodist,” felt it was purely a personal choice by Wilson. “He would like to be a great popular preacher. That he could never become in St. Andrew’s, which is distinctly a family church.”

Whatever the cause, the split was not acrimonious. On March 26, 1903 the members of the church presented Wilson with a good-bye purse of $2,600; a helpful $76,500 in today’s dollars considering he had no job.

Wilson’s replacement, the Rev. Andrew Gillies was chosen for his progressive ideas. The committee had informed him what they were looking for. “We want a family church, as broad a Christianity in its spirit, as aggressive as a modern business house in its methods, and as far reaching as human society in its ministry.”

By the time he was hired the Upper West Side had noticeably changed from one almost exclusively of private homes to scores of apartment houses. He told the New-York Tribune in November 1904 “It can honestly be said that the location of St. Andrew’s is one of the very hardest for aggressive and progressive church work. The middle West Side is filled with apartment houses. In these are hundreds of families who seldom, if ever, attend church services.” He said that an “aggressive church worker” who tried to reach out to them would find “the apartment house rigidly closed against his unwelcome intrusion.”

Nevertheless, the congregation was active in the community. A group of 30 women did house visits, a deaconess and a “student deaconess” looked after the “the poor, the sick and the indifferent,” according to the Tribune article.

Some of the progressive policies of St. Andrew’s were already in place when Gillies took the pulpit. Each summer middle and upper class residents abandoned the stifling city head for fashionable resorts or country estates. And the businessmen who stayed behind joined their families on the weekends. Therefore New York City churches routinely closed for at least three months during the summer. But not St. Andrew’s.

On June 5, 1904, The New York Press reported “St. Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church…this year will again follow its established custom of keeping open throughout the summer. The Rev. Andrew Gillies, pastor, will fill the pulpit until the first Sunday in August In his vacation it will be occupied by well known preachers of established reputation.”

Gillies’s popularity led to an increased membership and by 1906, the gallery that had been included in the 1889 but never constructed was necessary. The architects, now named Cady & See, filed plans on April 20, with an projected cost that would equal $42,500 today. The renovations included Formosa marble pilasters by P. M. & W. Schlichter. On September 29, the Record & Guide pointed out that the pilasters “highly pleased the pastor and board of trustees of that church, as well as meeting with the approval of the architects, Messrs. Cady & See.”

Gillies’s progressive ideas were carried on when the Rev. Fred Winslow Adams took over the pastorate in 1915.

He sent his thoughts on women’s rights to vote in a letter to the Empire State Campaign Committee that May. It said in part:

I am most heartily in sympathy with the movement for equal suffrage in this State and in the nation. Equal suffrage means not merely the right of women to vote, but the larger freedom of the State…Count upon me as ready at all times to do what I can to promote this agency.

Winslow came up with an clever means of finding fodder for a sermon in November 1916. He asked some of Manhattan’s leading citizens what they deemed “the most dangerous temptations that beset young men and young women in New York.” The results were, in some cases, surprising.

President Butler of Columbia University felt it was “the impulse to spend in excess of income.” (He felt this impulse applied only to men.) Reformer and criminologist Katharine B. Davis said the danger to young women was “The desire for pleasure of the kind that is typified in the glamour and glare of Broadway, of the theatres and cabarets.” And Mabel Cratty” of the Young Women’s Christian Association “boils her knowledge down to one word: ‘Clothes,'” said The Sun on November 21.

Interestingly, not one of those polled pointed to drugs, gambling or liquor as a dangerous temptation. Millionaire banker Jacob H. Schiff also had a one-word answer: women. The Sun commented on that, saying, “Mr. Schiff has stirred up a hornet’s nest for himself. Woman never tempts. She is invariably tempted.”

Nearly half a century after its construction the congregation sold its building. On June 29, 1937, the New York Evening Post reported: “Led by Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein, several upper West Side residents have purchased St. Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church at 120 West Seventy-sixth Street for $200,000 and will convert it into a synagogue in September.”

Rabbi Goldstein had organized the Institutional Synagogue in 1917. By now, it was known as the West Side Institutional Synagogue. Like the pastors of St. Andrew’s, he was a progressive, and his goal was to cater to young American Jews who could not connect with the old European-style synagogues.

His innovations–which later became commonplace in Modern Orthodox synagogues–included English language sermons and cultural programs, some of which might shock traditional congregants, like dances.

In 1958, architect David Moed was commissioned to renovate and remodel the former rectory building.

The dedication took place on April 30, 1938. The New York Post reported “West End Institutional Synagogue today takes over [the] building at 120 West Seventy-sixth Street, which has been called ‘the handsomest and most imposing church structure erected by Methodists in New York.'” Along with Rabbi Goldstein, the speakers included lawyer and politician Charles H. Tuttle, Congressman Bruce Fairchild Barton, and entertainer Eddie Cantor. A dinner-dance followed at the Waldorf-Astoria.

The congregation took over the building at a time of international upheaval and danger. Rabbi Goldstein’s first Rosh Hashanah sermon here addressed the imminent threat of war. “We are facing war because we have warred against God’s law,” he declared.

The coming war had, of course, much to do with the rise of Adolph Hitler, whose racist agenda struck terror in the hearts of Jews world-wide. On March 26, 1938, The New York Sun reported “At the West Side Institutional Synagogue, 120 West Seventy-sixth street, Rabbi Herbert S. Goldstein likened the leaders of Germany to ‘some maddened beast which seeks to plunge the world again into the hell from which it has so recently and so tortuously emerged.’ He declared that the United States, in inviting persecuted peoples to come to this country, has assumed the moral leadership of all nations.”

The synagogue was on the front lines of relief as war raged throughout Europe. On December 19, 1944, The New York Sun reported, “Congratulatory messages were read last night from Gov. Thomas E. Dewey and Mayor F. H. LaGuardia at a meeting in the West Side Institutional Synagogue…at which the first unit of a national plan to aid war veterans through synagogues was launched.” The plan, outlined at that meeting, offered veterans “membership in the synagogue club rooms, economic aid through placement and employment assistance panels, assistance to their wives and children and vocational and family aid in neighborhoods on a non-sectarian basis.” The Governor praised the plan as being “devoid of any humiliating suggestion of charity to our demobilized fighting men.”

Following the war young dances were a popular activity in the 76th Street space. They were most often coupled with a more edifying component. In November 1948, for instance, a newspaper announcement was entitled “FREE–DANCE–FORUM.” Young people coming to dance that night would also hear author and Zionist Beinush Epstein speak on the “Fiasco of Partition.”

An exception was the Leap Year Dance on January 17, 1948. But although the event was purely for dancing (with Sandy Block and his orchestra providing the music), the trade-off was a $1.25 admission.

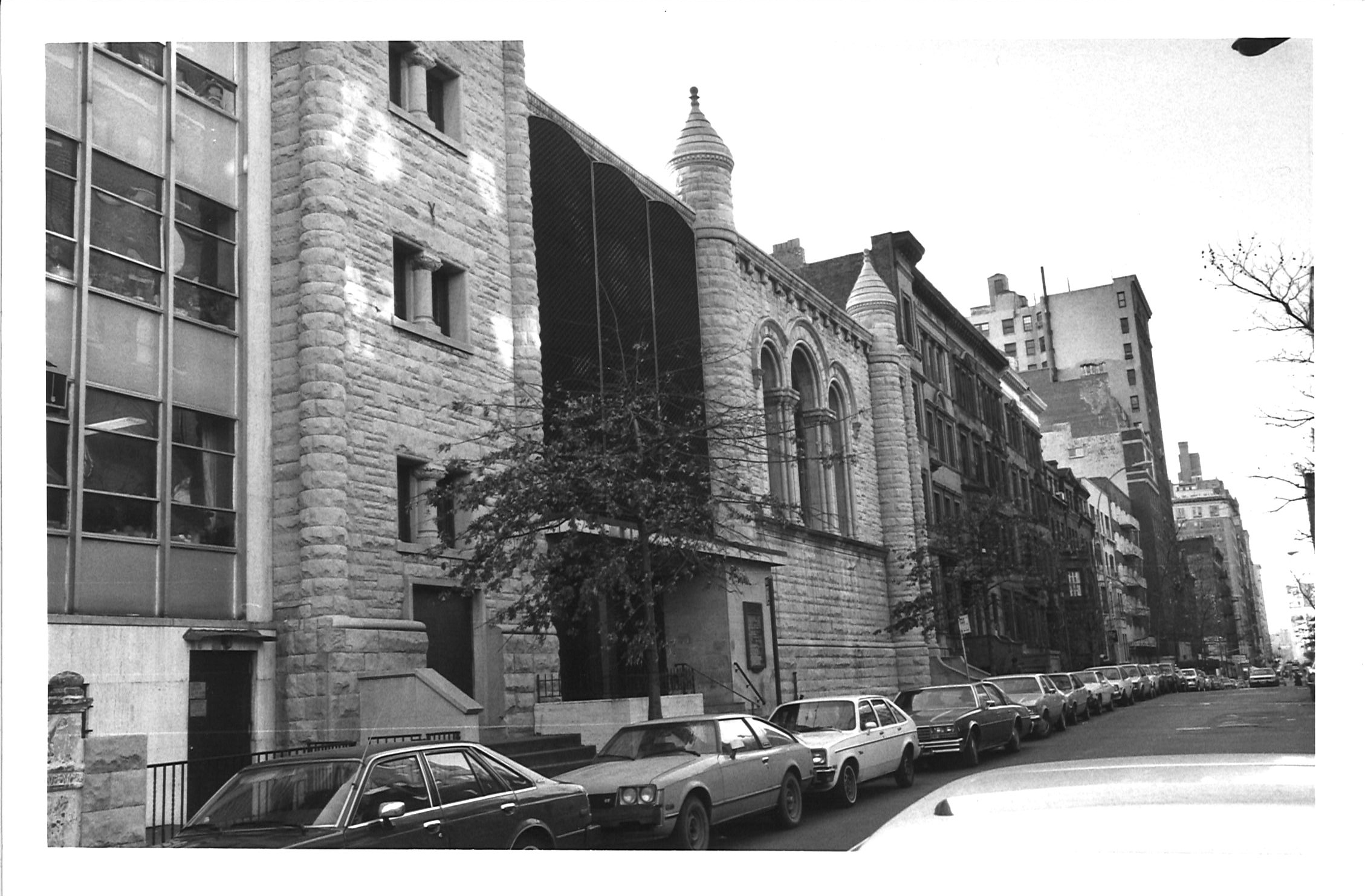

In 1958, architect David Moed was commissioned to renovate and remodel the former rectory building. The plans, which called for removing the stoop, included an apartment on the first floor, classrooms on the second, a social hall, banquet hall, “bazaar” and kitchen on the third and classrooms and a “clubroom” on the upper floors. With a late 1950’s disregard for historic consideration or architectural conformity, he replaced Cady & Co.’s Romanesque Revival facade with institutional metal panels.

Seven years later a devastating fire tore through the main church. Architect Emory S. Tabor restored and preserved what he could; but the roof and dome had collapsed and the tall gable was now gone. Tabor’s renovations included a modern, rather severe, entrance which, like Moed’s changes, were more in keeping with current architecture than an attempt to echo the overall design.

After more than eight decades in the former Methodist church, the West Side Institutional Synagogue continues to be a vibrant force in the Upper West Side’s Jewish community.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Explore Houses of Worship

Be a part of history!

Stay local to support the nonprofit currently at 120 West 76th Street: