Keeping the Past for the Future

Urban ArchaeologistsExplore the layers of history on the Upper West Side through the field of archaeology! As our neighborhood has grown and changed throughout time, traces of past people, roads, buildings, and lives are left underground. Let’s peel back those layers under our feet to learn more about what came before us.

In this program, we will examine maps and photographs to watch change appear. Then, we will explore Seneca Village and other famous archaeological sites to learn what excavation has uncovered about our neighborhood’s past.

The Build-Up of History

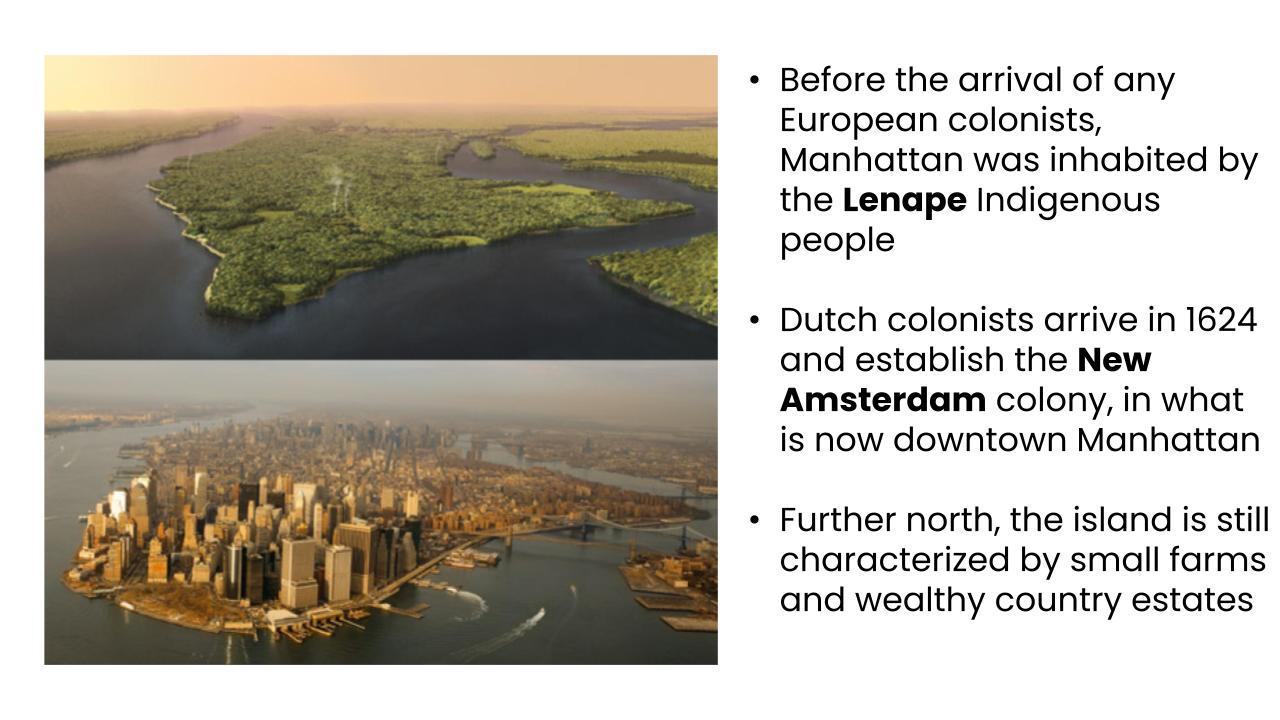

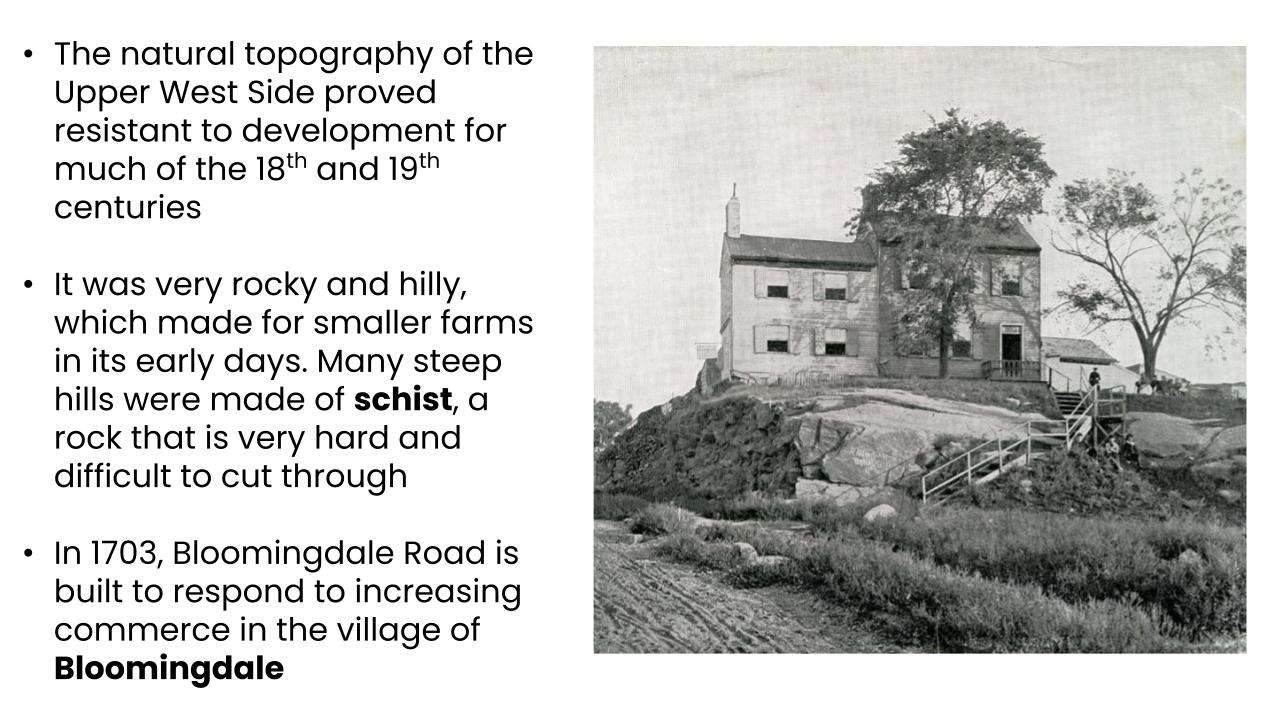

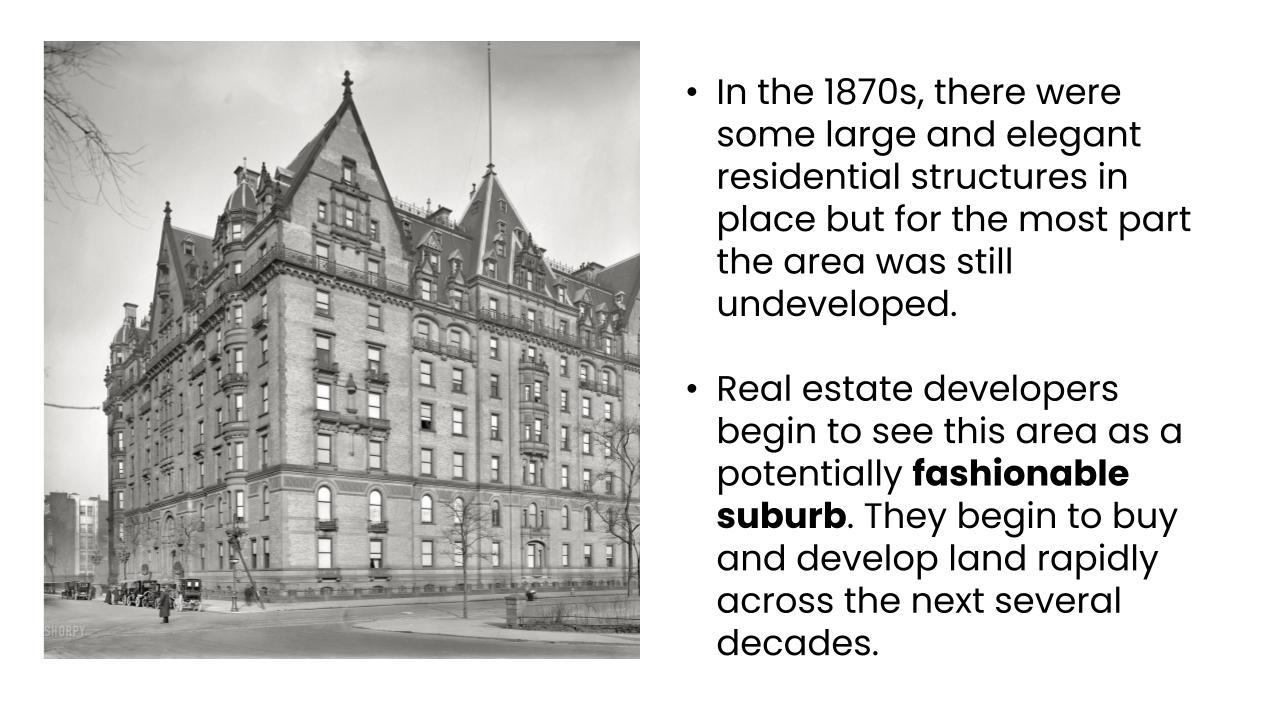

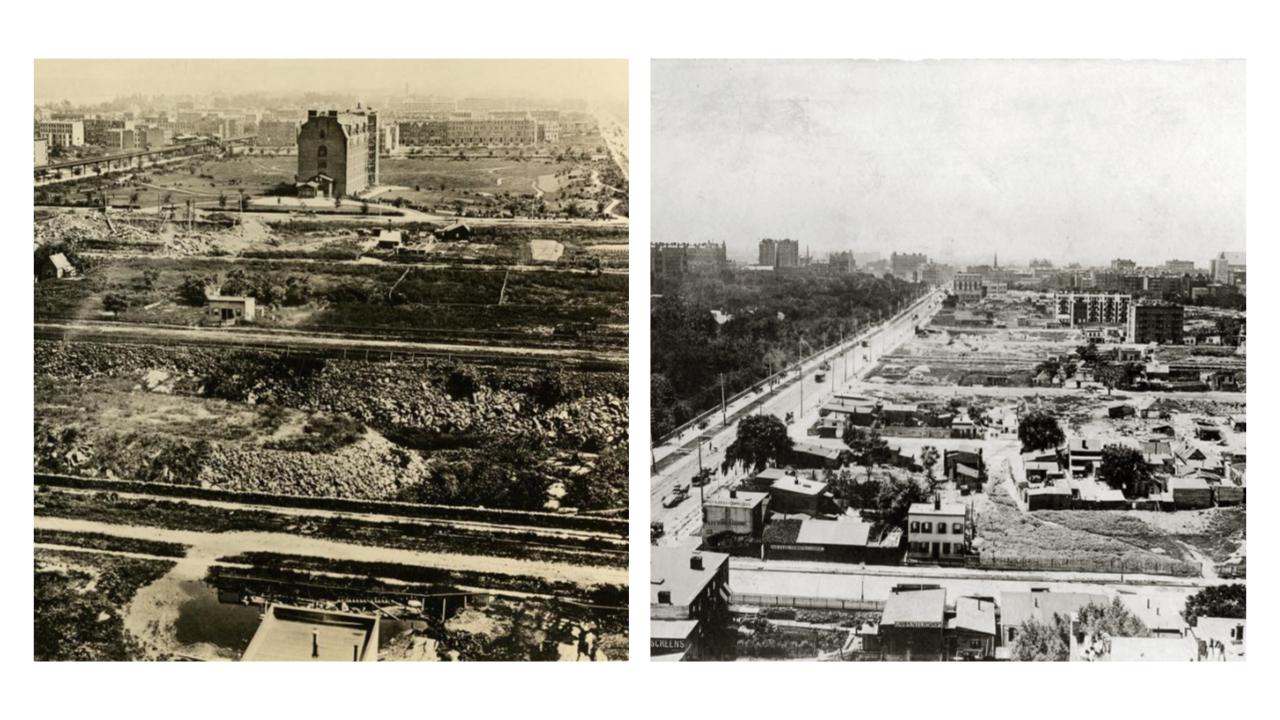

The Upper West Side has drastically changed over the years, from the pre-colonial period through to the present day. Even after New York City’s founding, this neighborhood remained very rural for many years, characterized by farms, small villages, and country estates rather than the crowded gridded streets and urban development more common downtown.

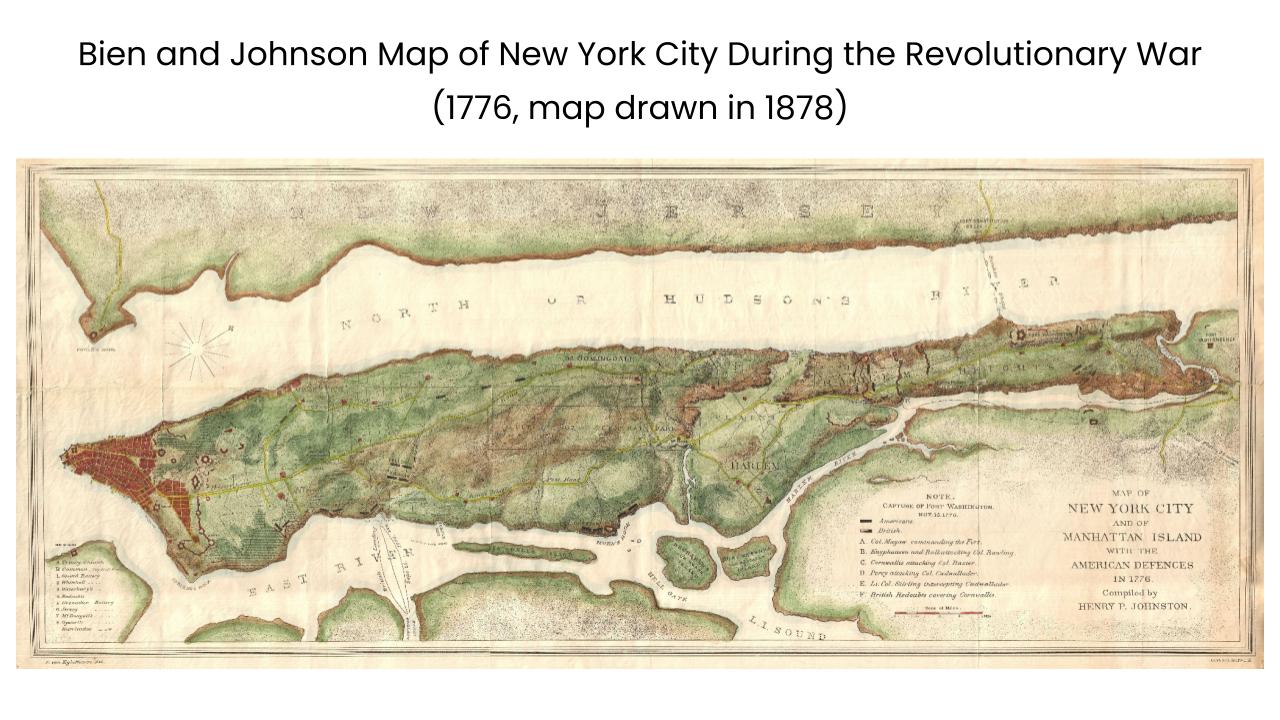

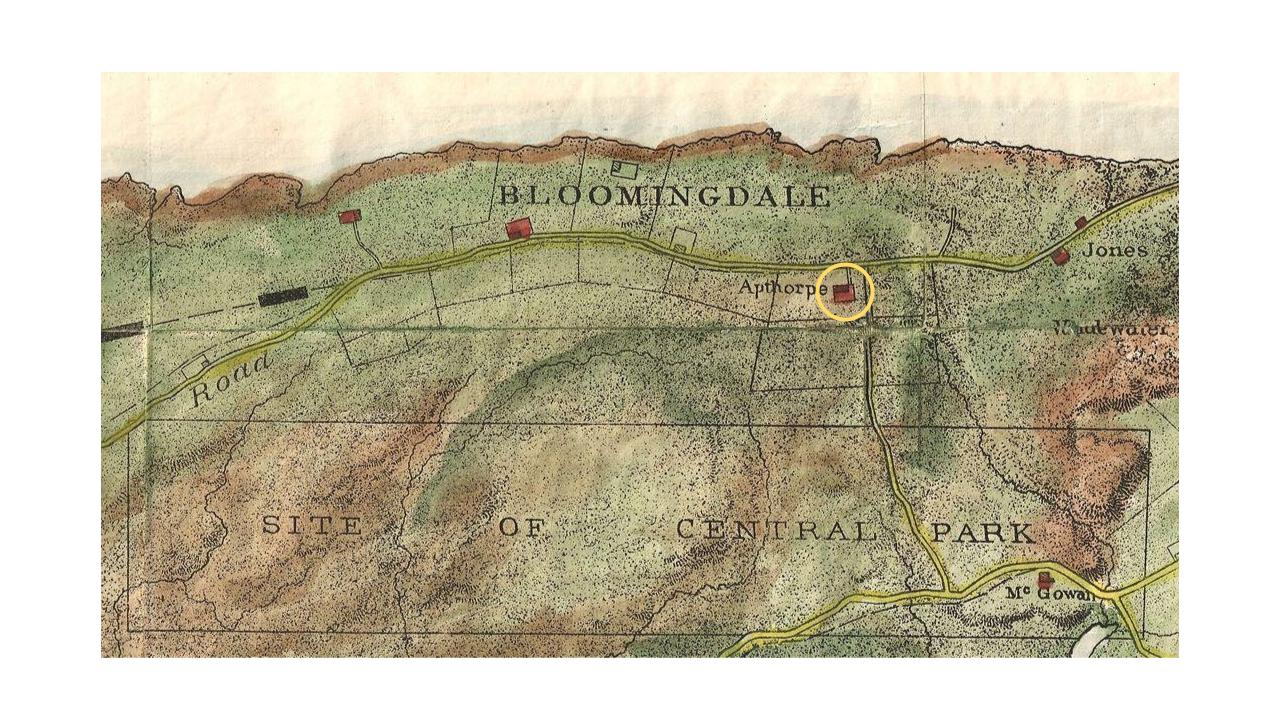

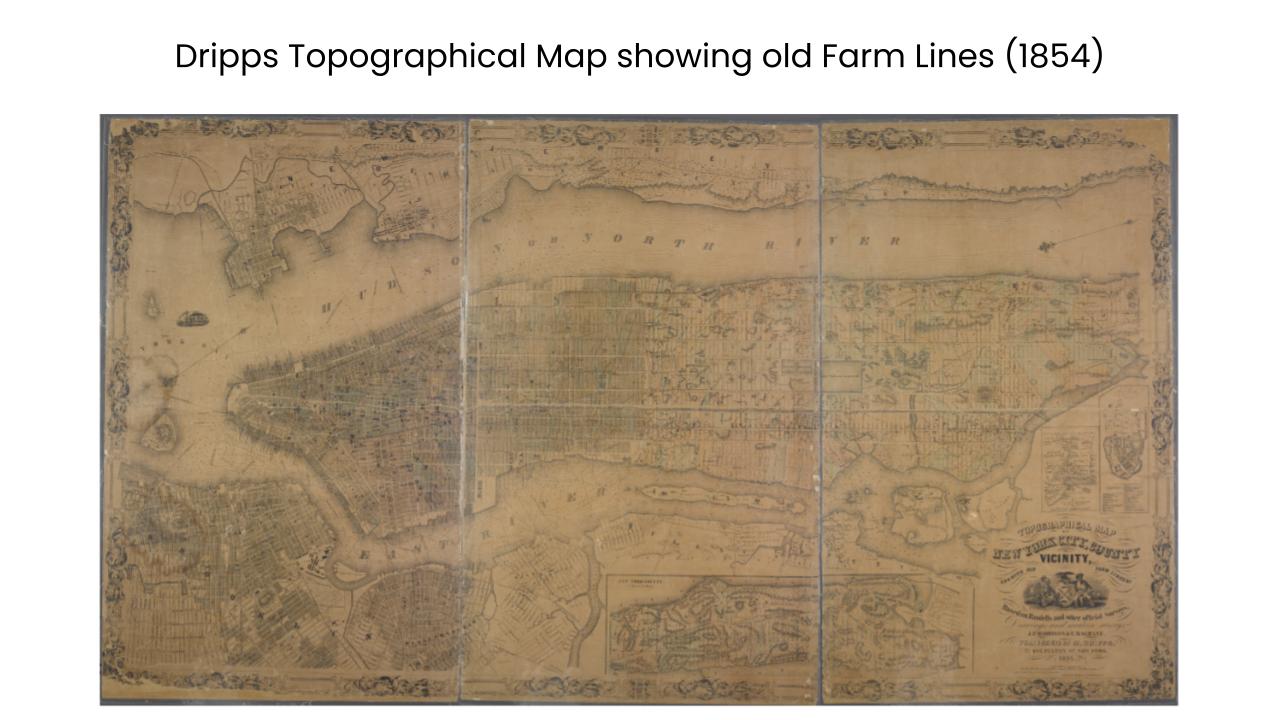

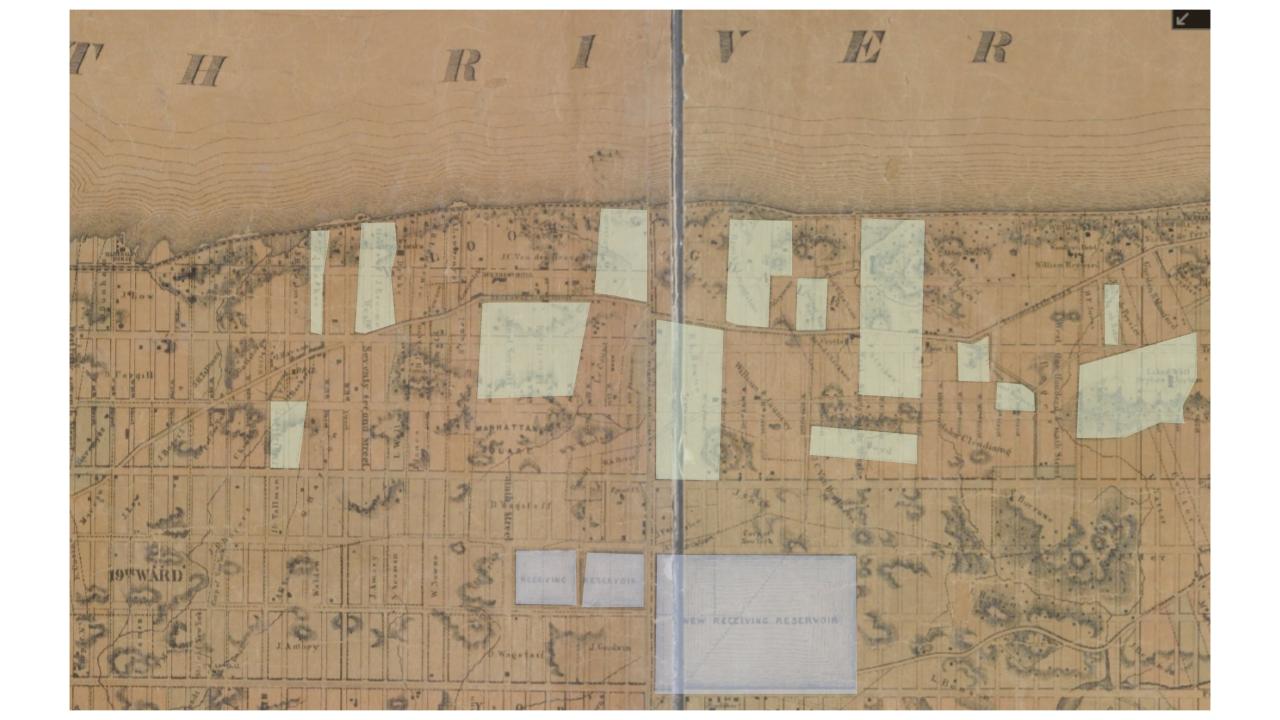

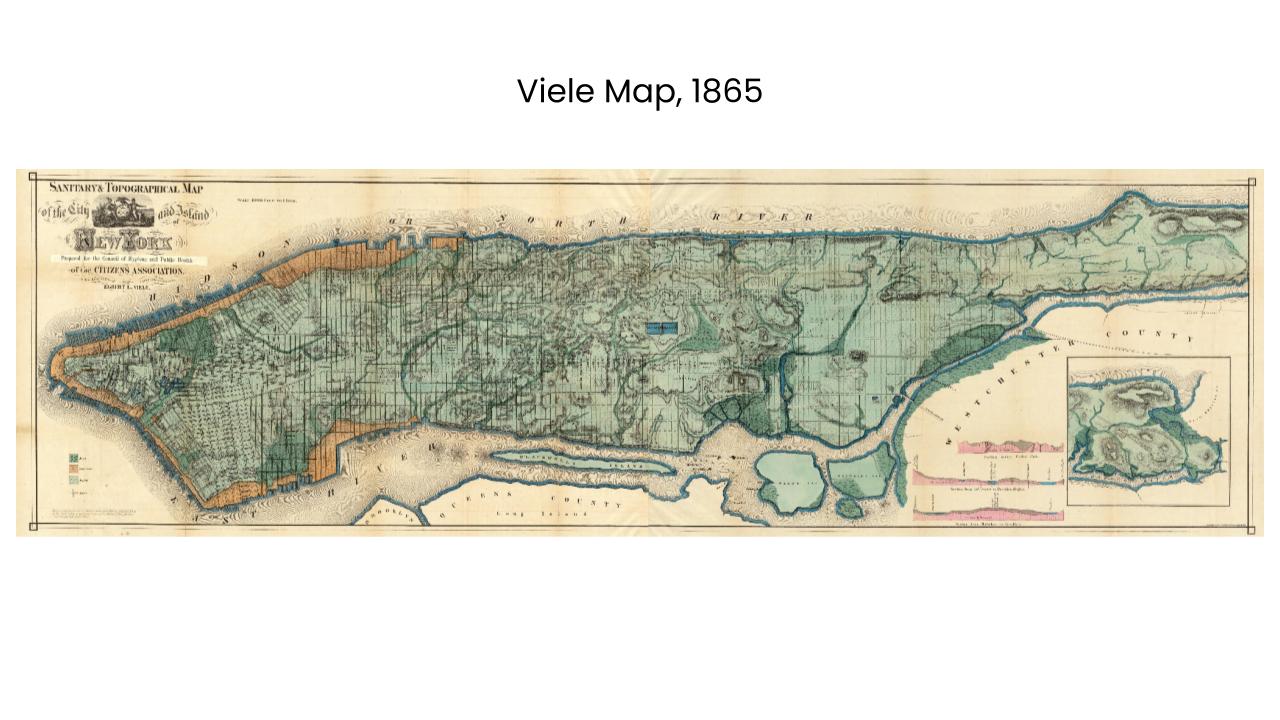

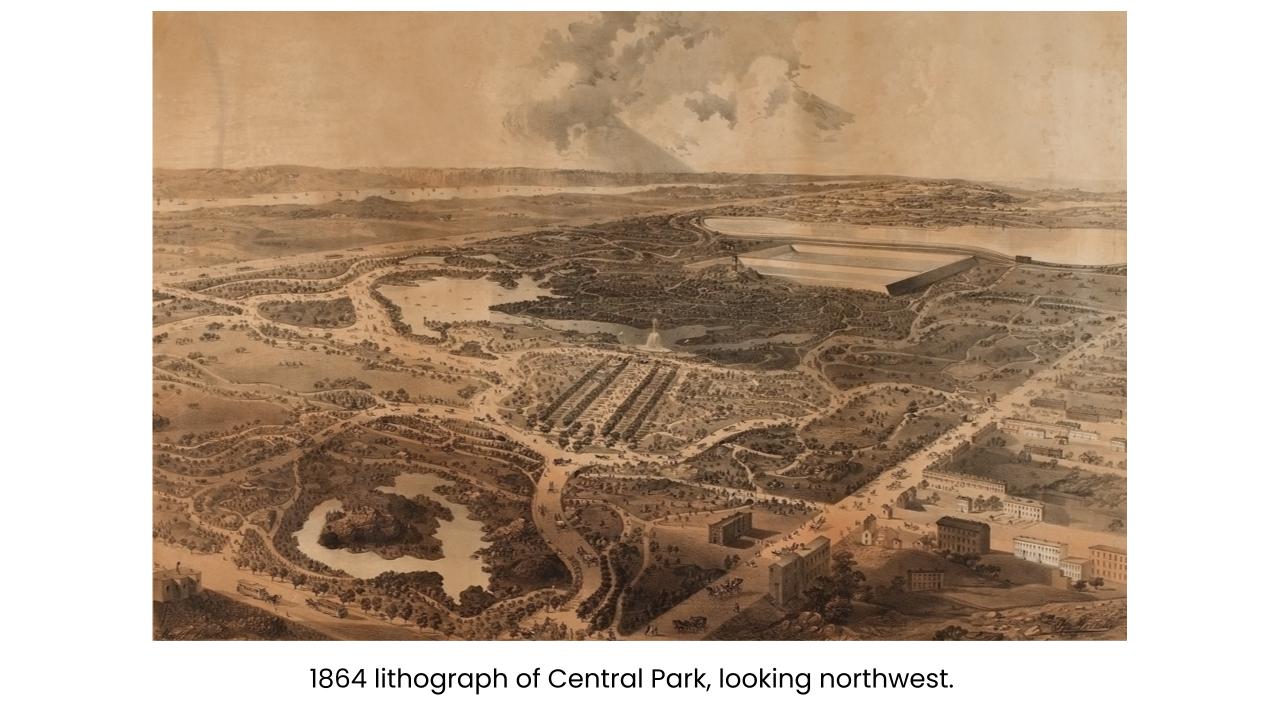

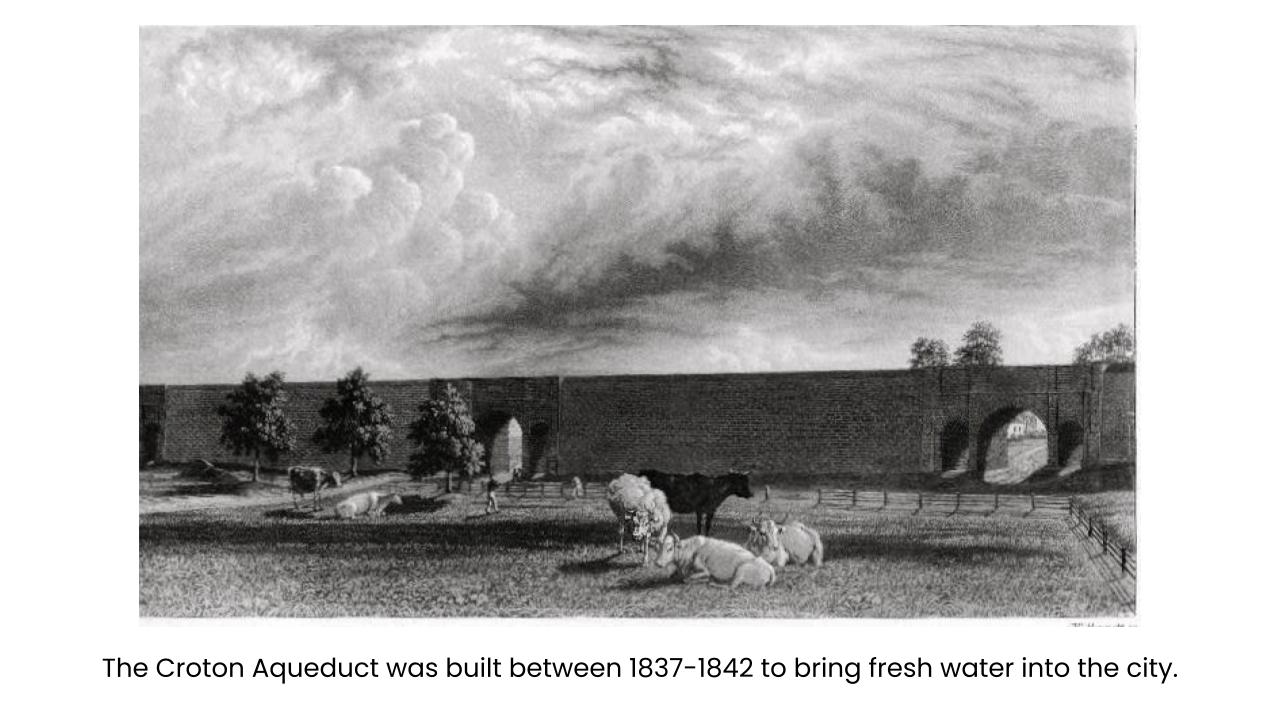

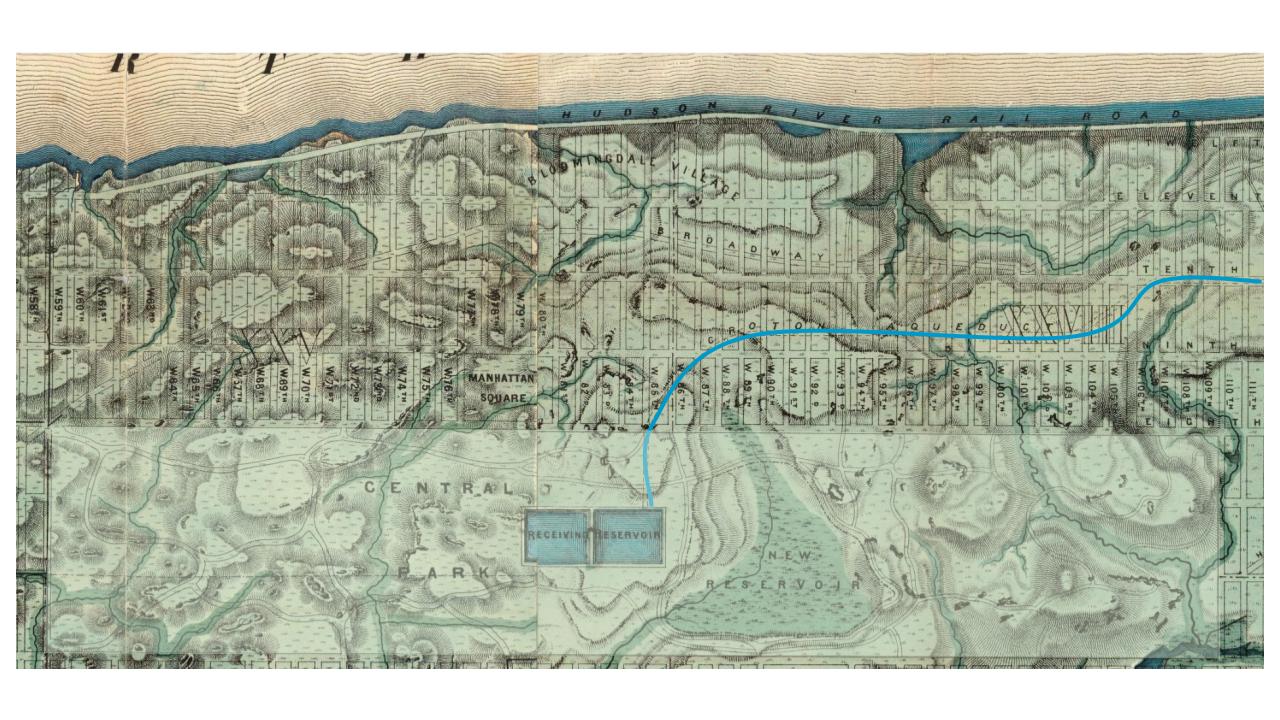

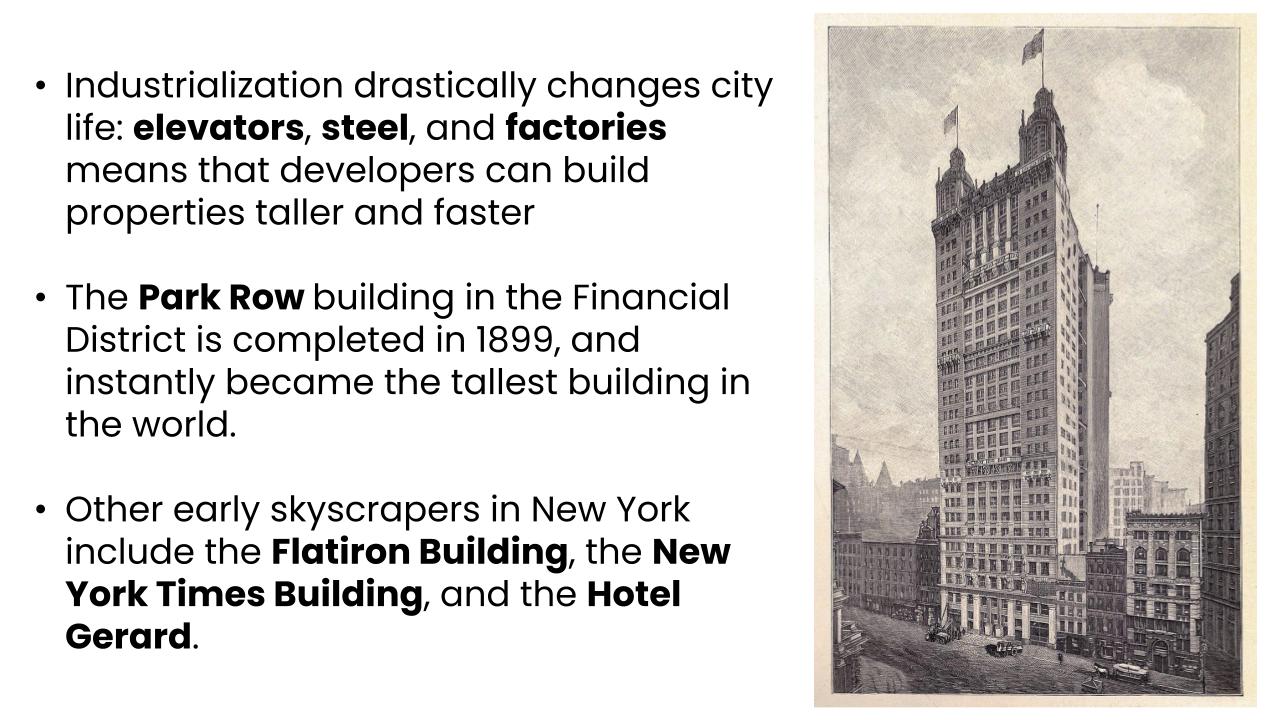

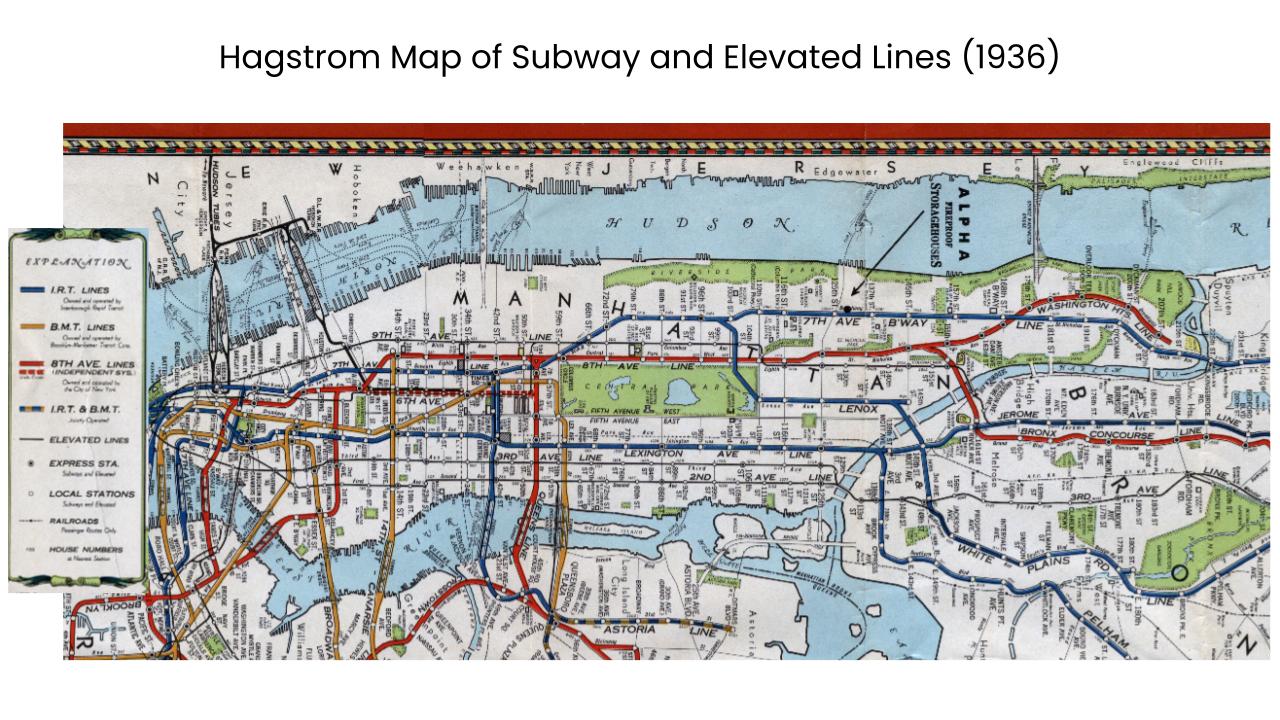

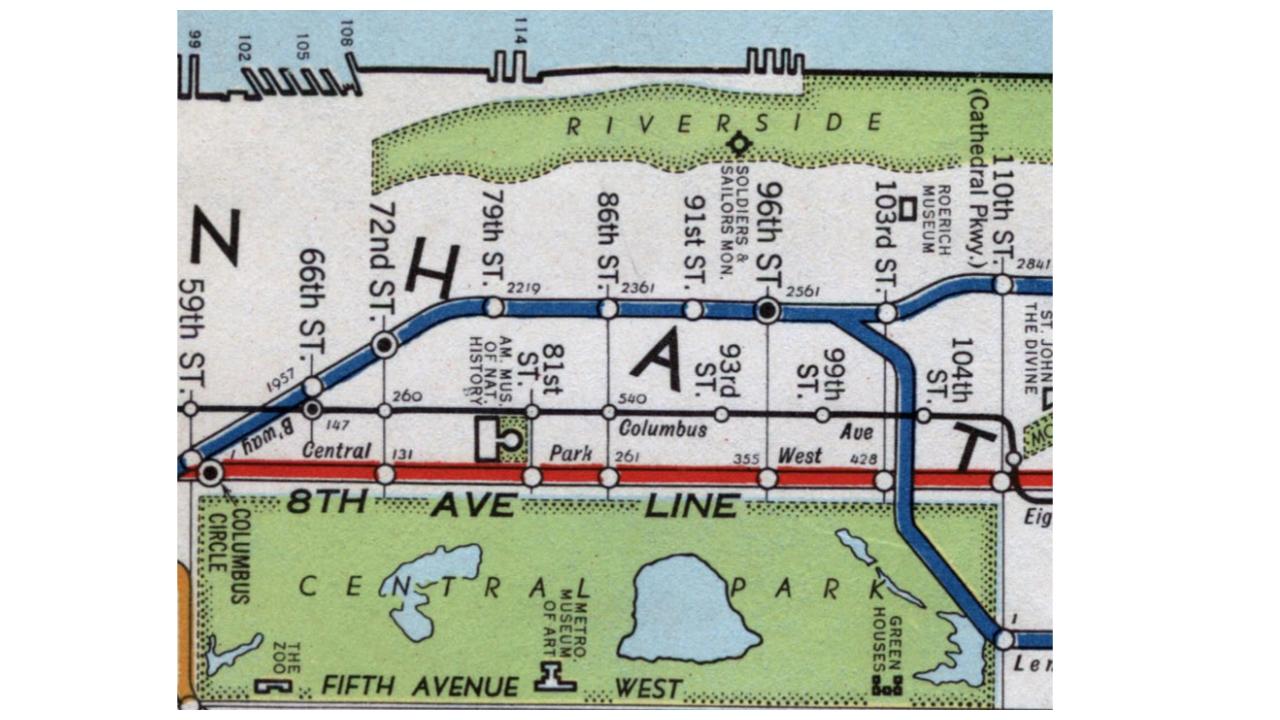

Watch these maps from 1776, 1854, 1865, and 1936 layer on top of each other. They each represent different eras of change; we can see roads, farmlands, buildings, and features like the Croton Aqueduct, Central Park, and subways arrive over the years. Check out the slides below for more details about this changing history!

Session One Slides

How has the Upper West Side changed throughout history? Beginning just before European colonization, these slides take us through the neighborhood’s development.

They use maps and other primary and secondary sources to trace those changes, allowing us to see how waves of change arrived one after the other.

What traces of those periods could still exist beneath our feet?

Make Your Own Map

Using the blank neighborhood outline on the right, you can use the maps featured in the slideshow and gif above to make your own layered map of the Upper West Side. Note that they dark black outlines represent features of our neighborhood today, including the current coastline and the location of Central Park. The light gray shape at the top is the original coastline of the island, and Broadway’s modern course is represented by the dotted line.

Choose a different color for each time period, and use it to sketchout that map’s prominent features: roads, buildings, farms, parks, train lines, and more.

Session Two Slides

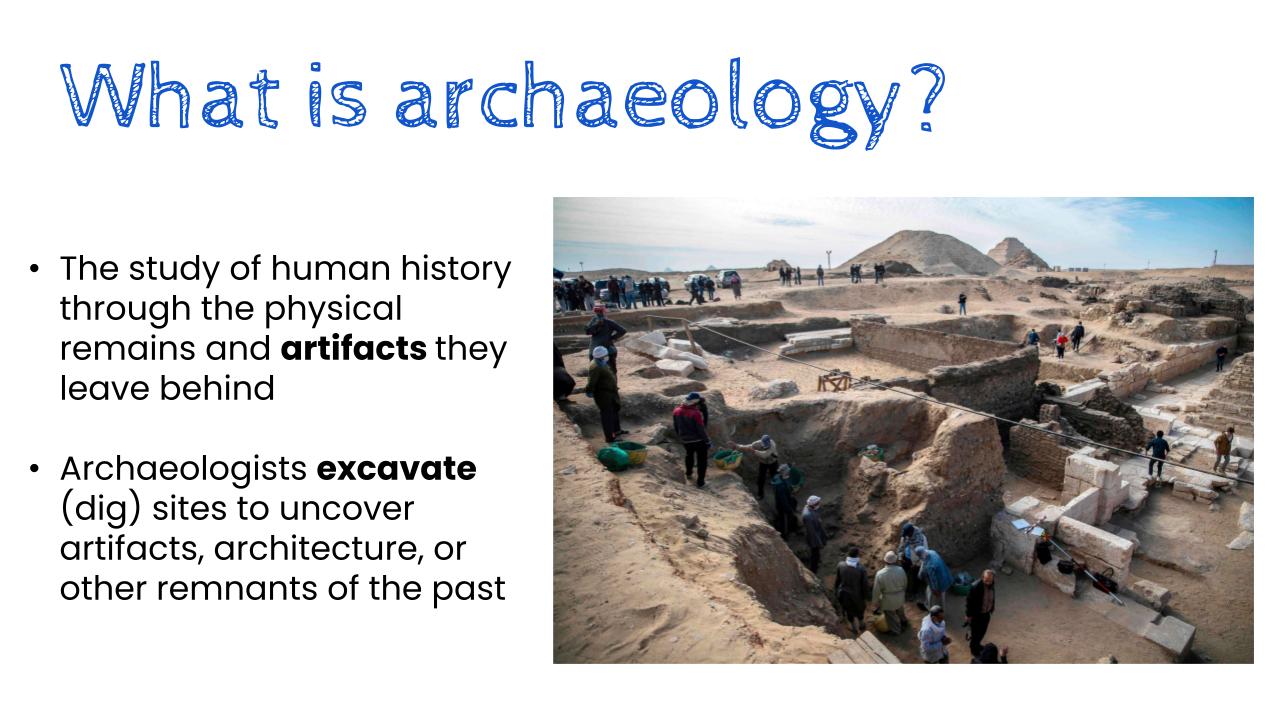

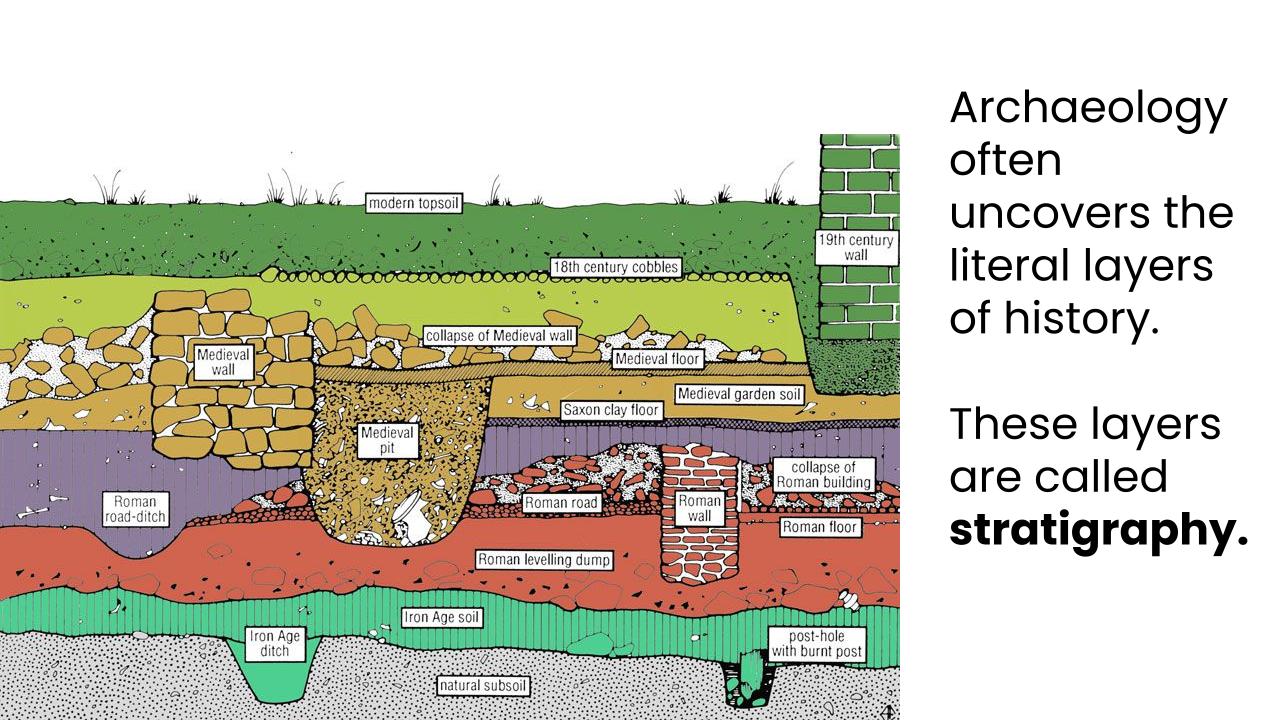

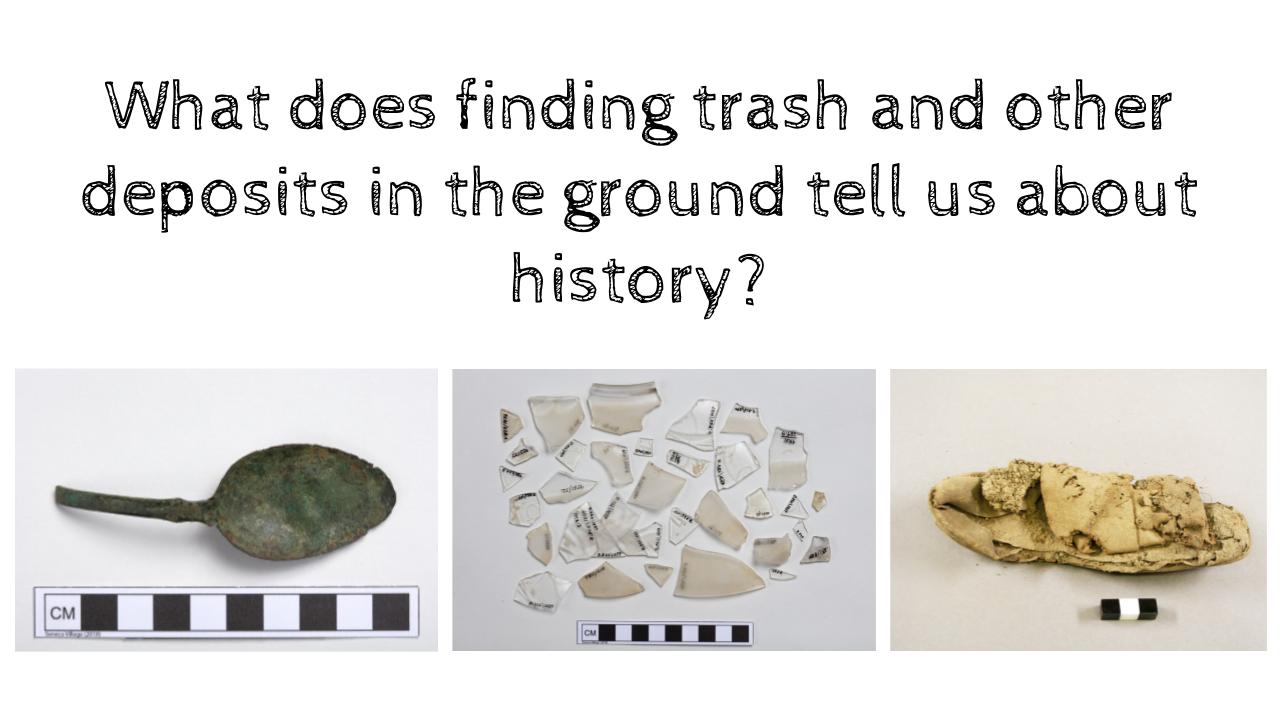

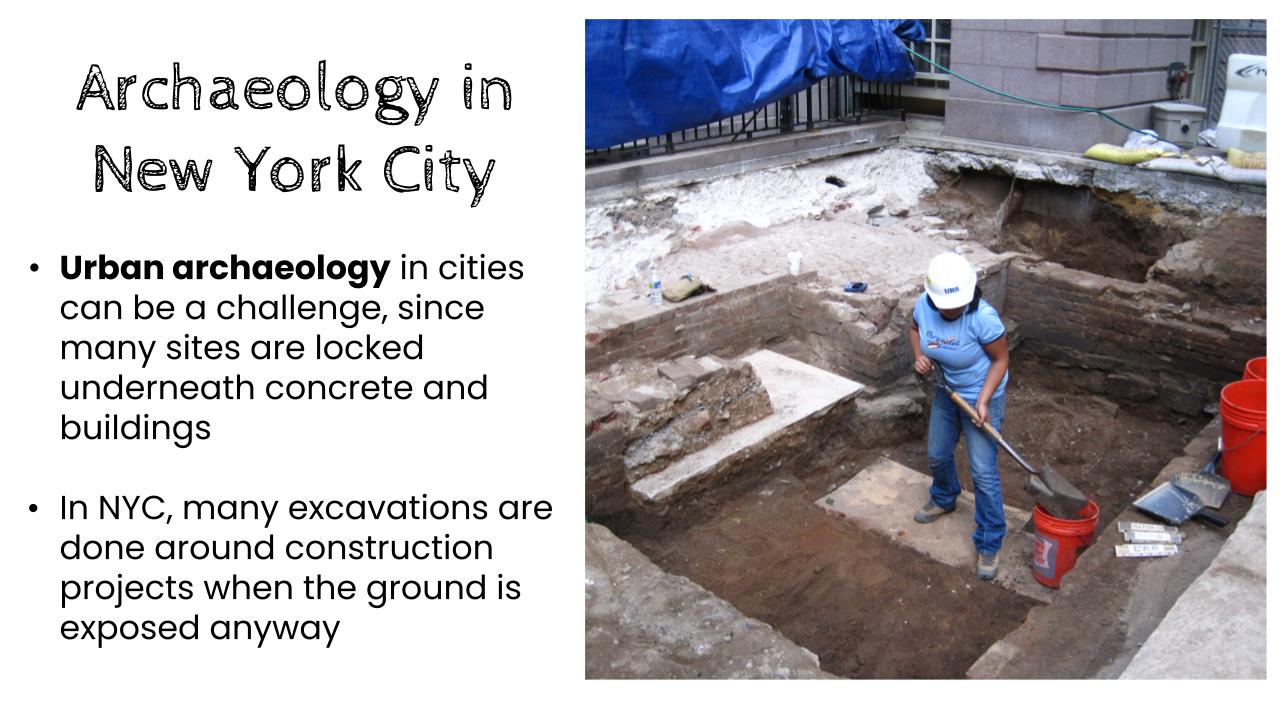

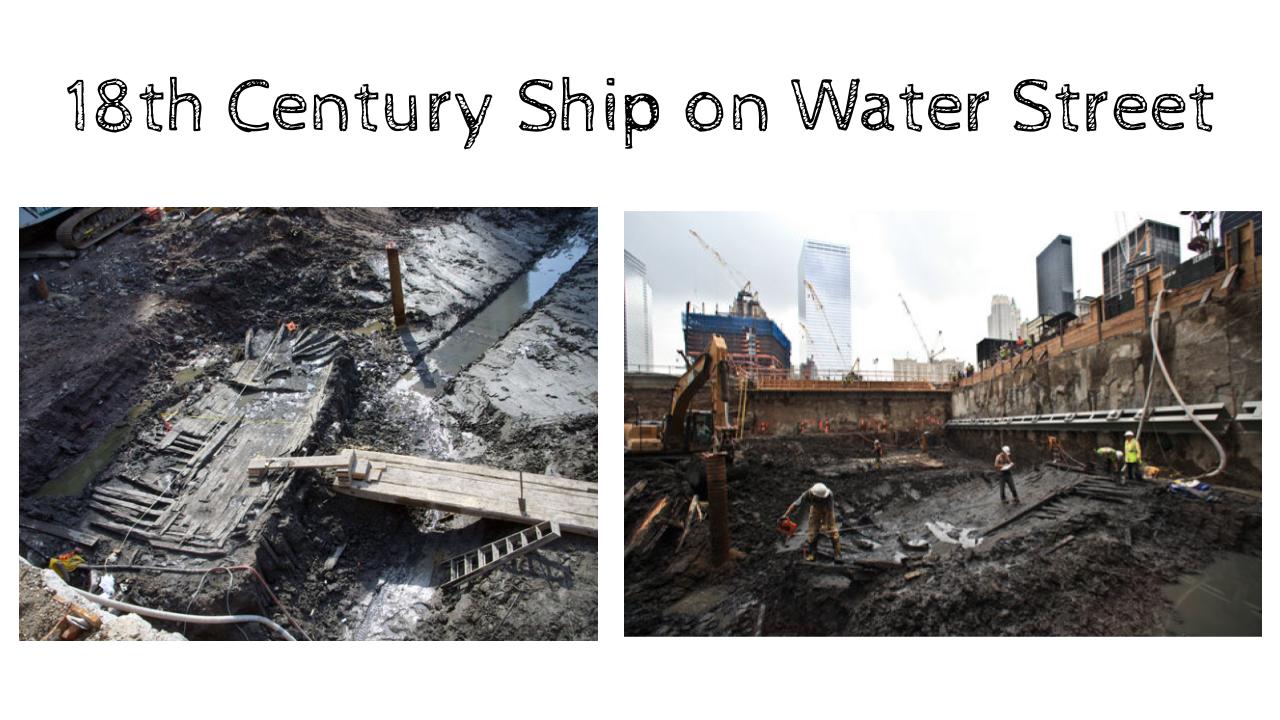

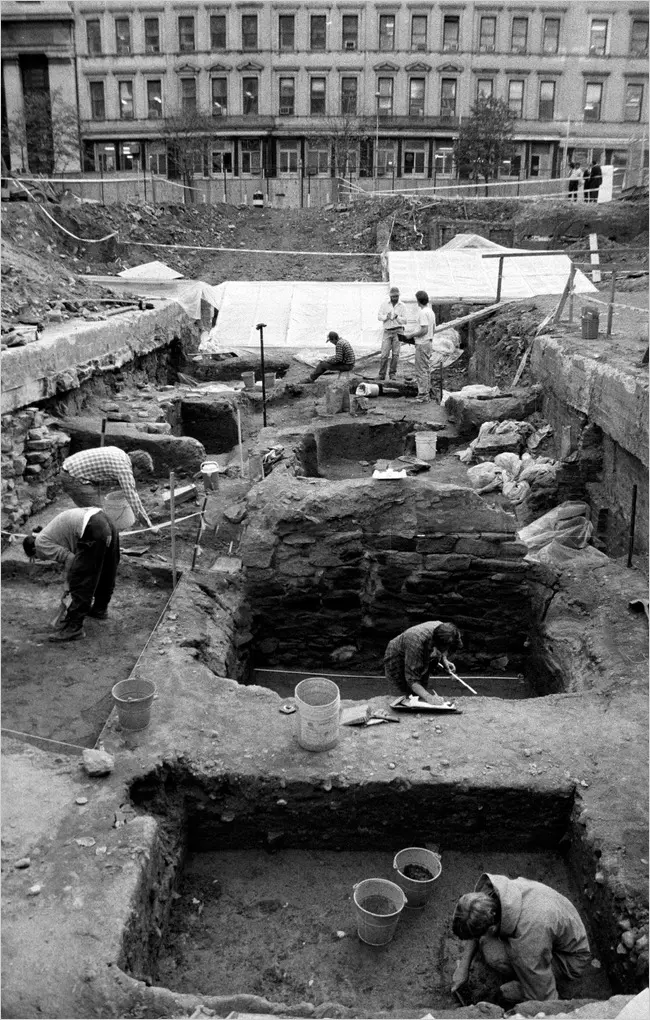

What exactly is archaeology? We can study human history by literally unearthing the remains, artifacts, and architecture that groups have left behind. Follow along with these slides to learn more about the field.

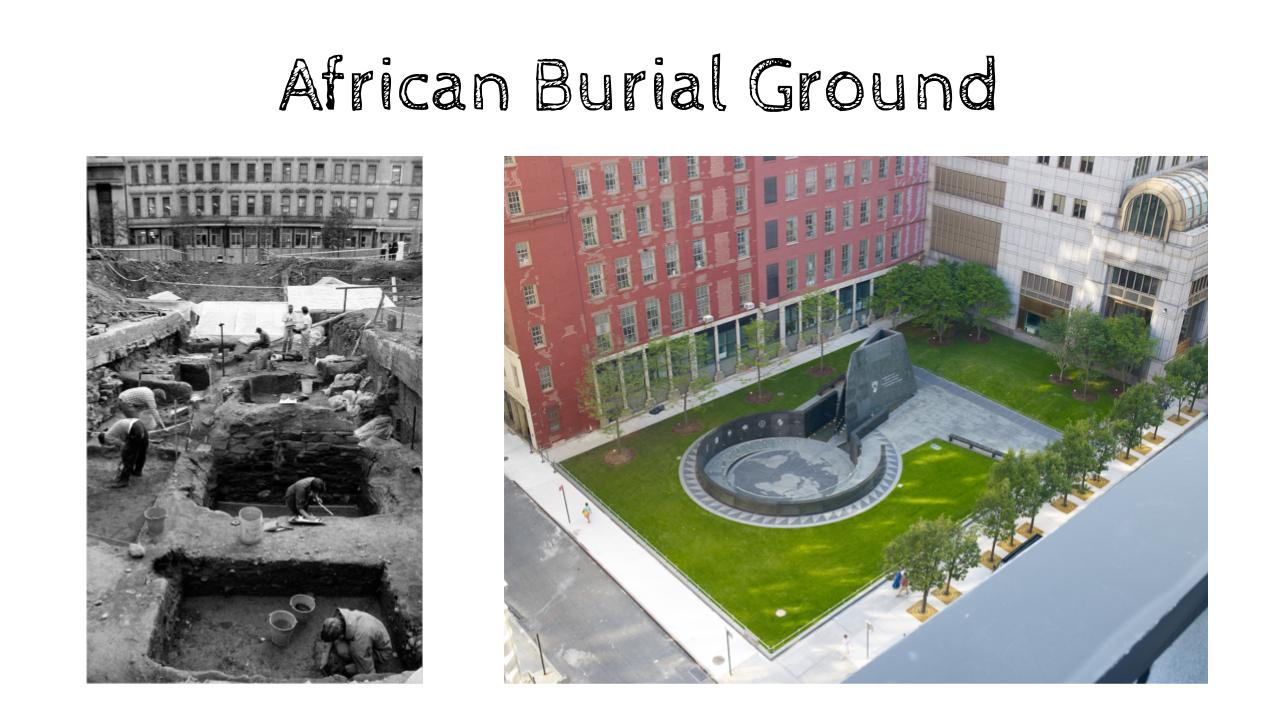

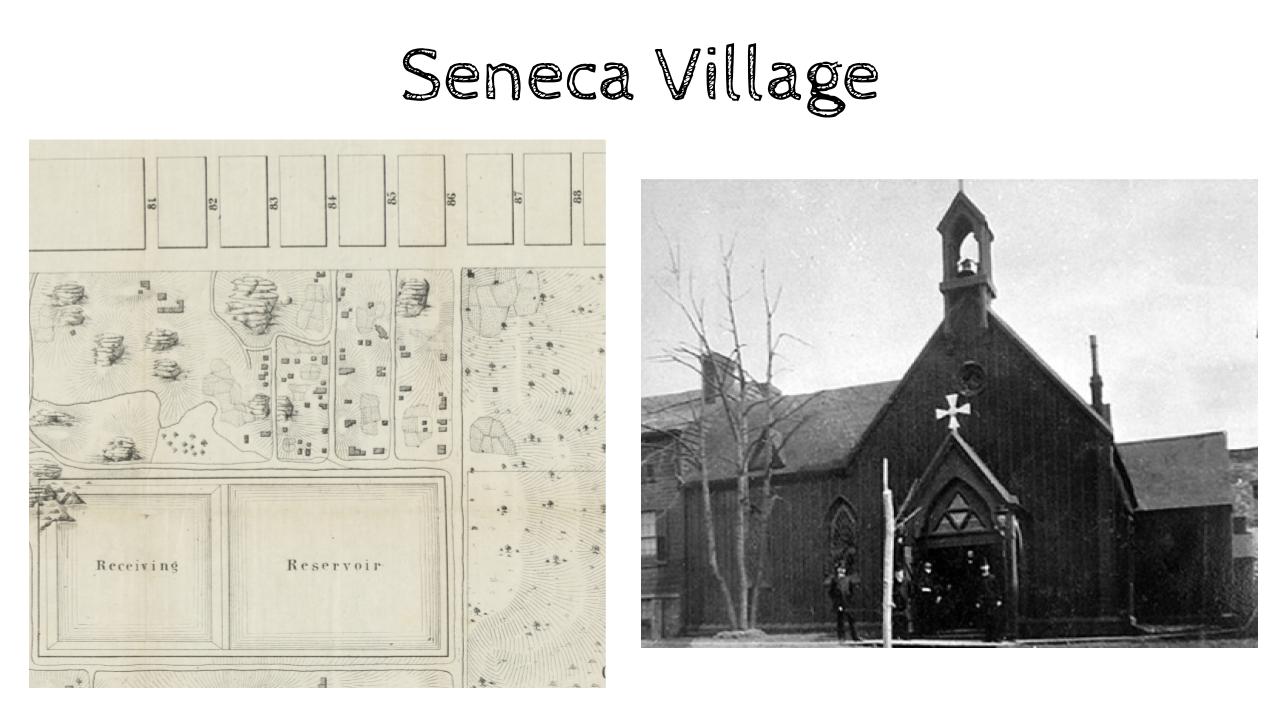

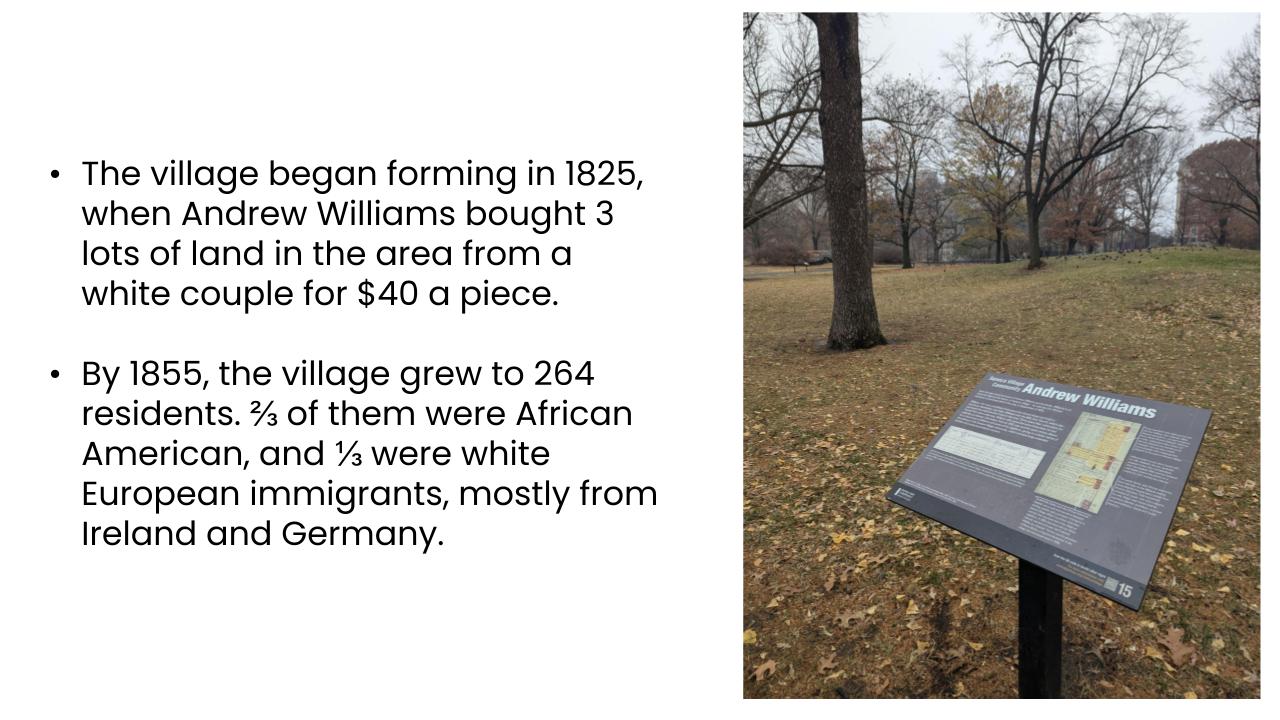

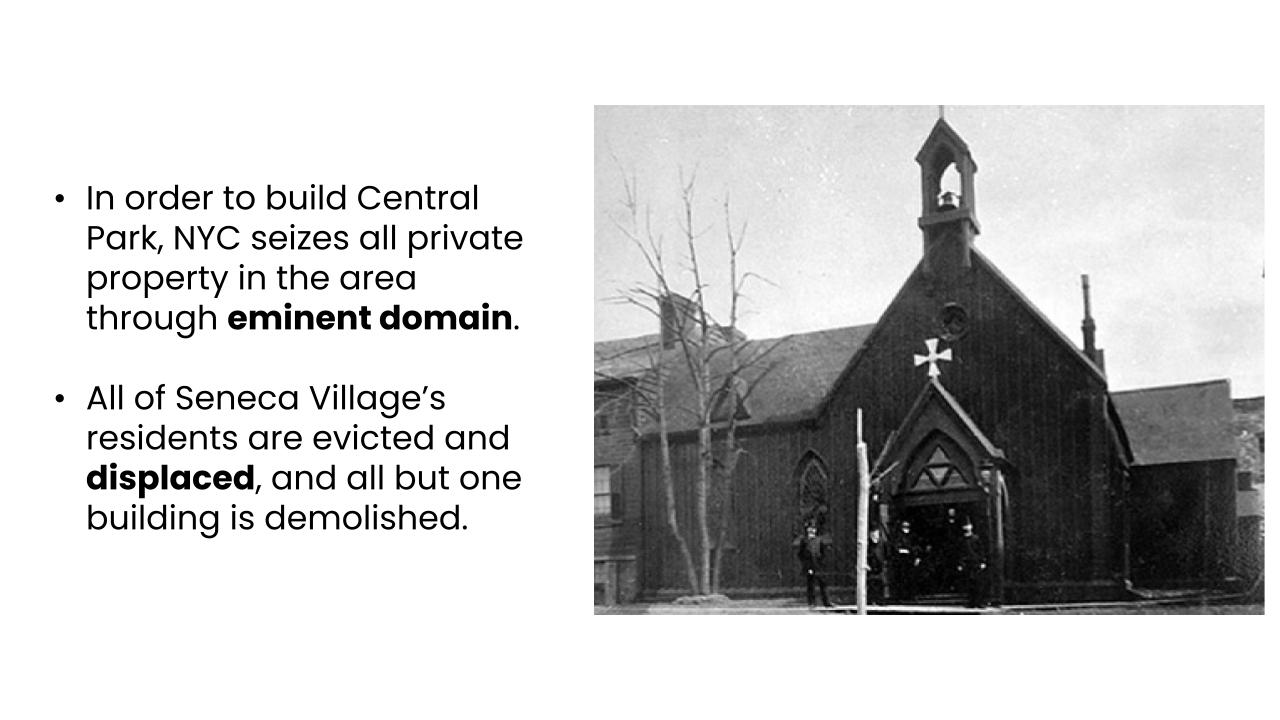

Let’s also dig into some of NYC’s most famous archaeological sites, including Seneca Village. This predominantly Black village was destroyed so that Central Park could be built. Archaeology can help us understand more about that dark legacy, as well as the lives of the residents to built and lost that community.

TAKE A WALK THROUGH SENECA VILLAGE

Today, you can find traces of Seneca Village inside Central Park, roughly between West 82nd and West 89th Streets. Thanks to the Central Park Conservancy, the park now features an open air exhibit tracing prominent landmarks of the historic village. In this video, we take you along a peaceful walk through Seneca Village’s main stretch.

Where should we dig next?

West 84th and Broadway - Edgar Allan Poe's UWS Home

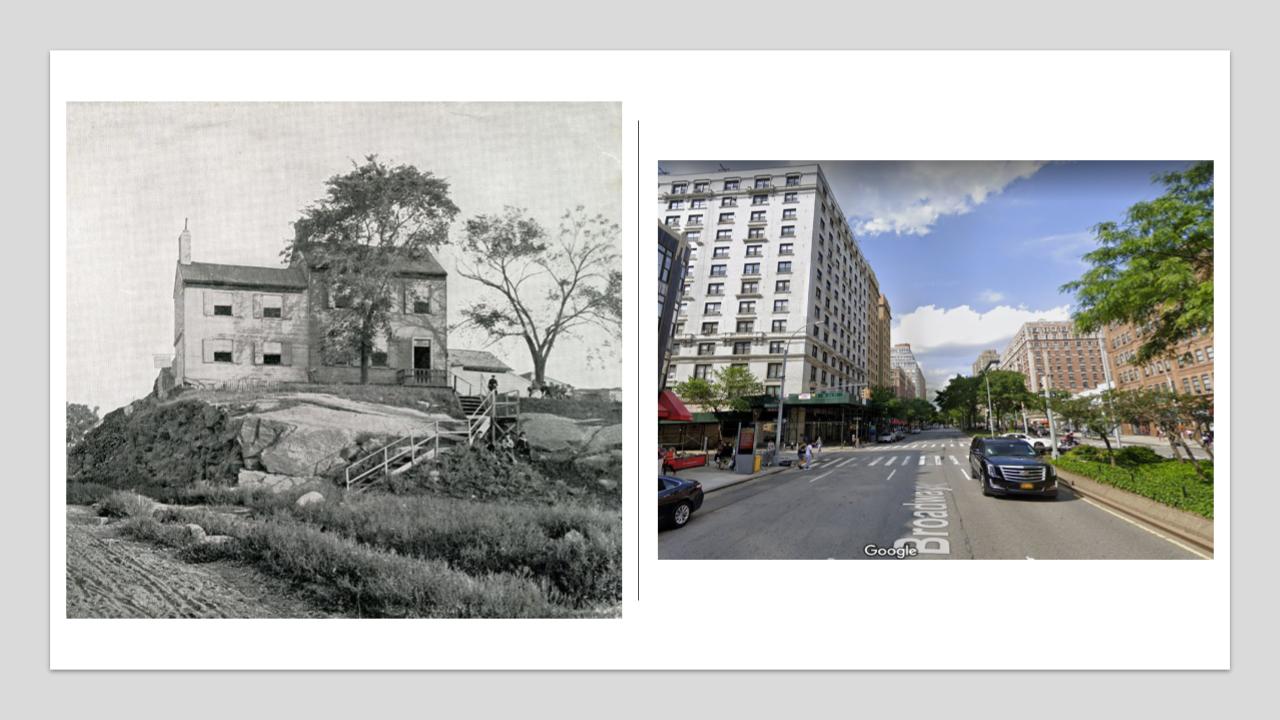

A farmhouse once stood near the present day intersection of West 84th Street and Broadway; in 1830, the 213 acre property was purchased by Patrick and Mary Brennan, who occasionally rented rooms to boarders. In 1844, their new tenants were none other than horror writer Edgar Allan Poe and his family. He proportedly wrote “The Raven” during his time on the Upper West Side, perhaps his most famous eerie work. But where exactly did the farmhouse stand?

Conflicting accounts place the farmhouse both east and west of Broadway. There are even two plaques celebrating those two locations, one to the west on The Alameda at 255 West 84th Street, and one to the east formerly located on Eagle Court, a building now being demolished, previously of 215 West 84th Street. Could archaeological excavation shed some light on the exact location of this spooky farmhouse?

Great Hill - A Revolutionary Army Encampment

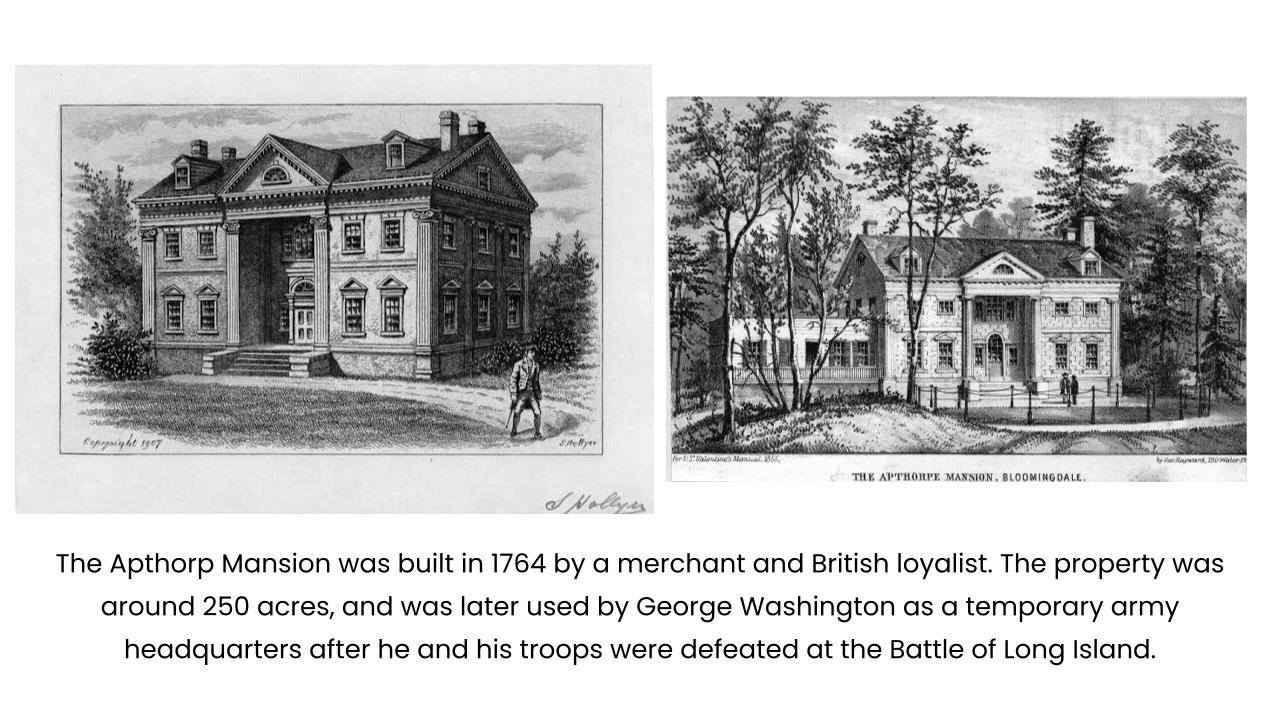

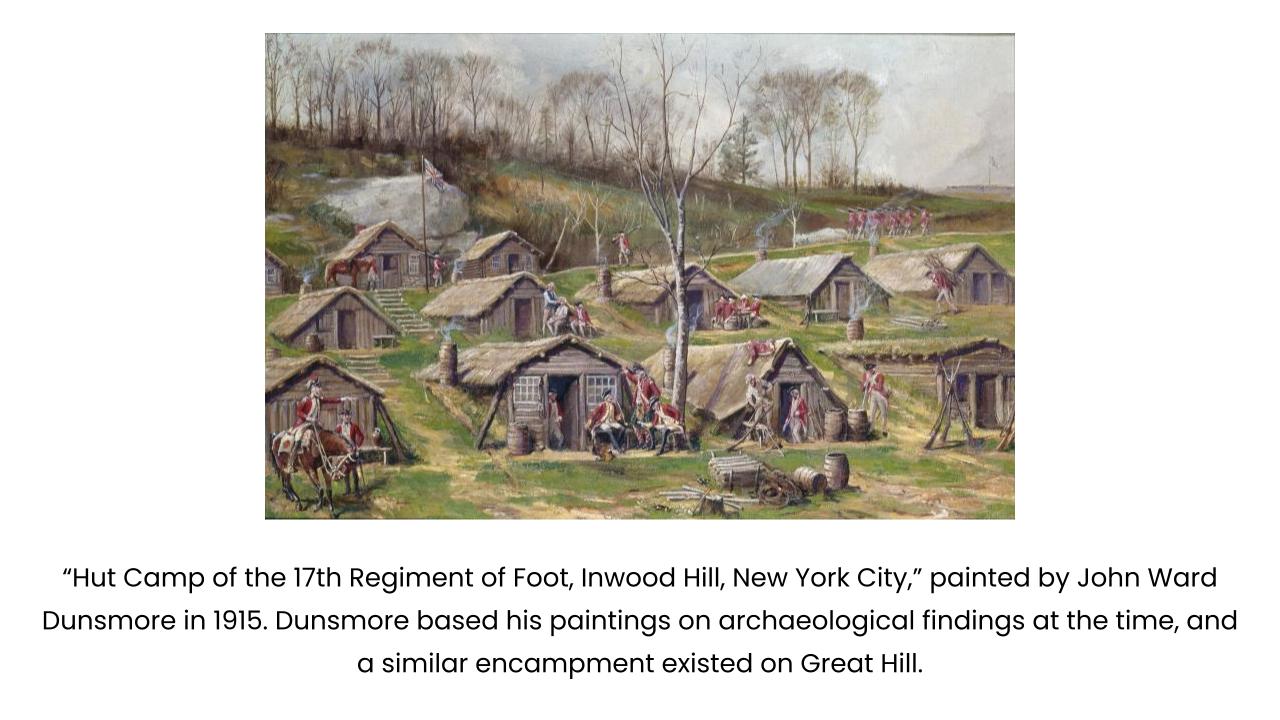

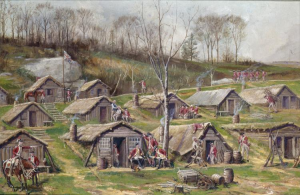

The Upper West Side was alive with activity during the Revolutionary War. New York City remained primarily under British control during the war, particularly after George Washington’s defeat at the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776. There were several British army barracks throughout the city, including in Inwood Hill Park (see John Ward Dunsmore’s 1915 painting below, on the right) and another in the Great Hill section of Central Park today. Great Hill’s high vantage point would have afforded troops strategic views of the surrounding areas.

While constructing this area of Central Park nearly a century later, Frederick Law Olmstead discovered evidence of those barracks underground. We are left wondering what modern archaeological excavations could uncover today…

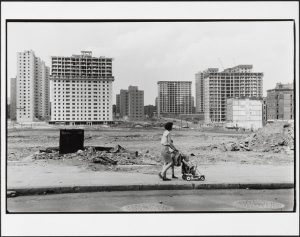

Lincoln Center - San Juan Hill

San Juan Hill was a predominantly Black and Puerto Rican neighborhood that existed near the present day Lincoln Square neighborhood; you might have seen LW!’s own research series all about it. Originally developed as a form of Hell’s Kitchen north, it saw many waves of immigration and community building throughout the decades. African American families leaving downtown neighborhoods like Greenwich Village settled here in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, joining existing communities of Irish immigrants. Later waves of settlement brought a rich community of Puerto Rican immigrants. During the 1940s and 50s, it was demolished in an urban renewal initiative that created campuses like Lincoln Center, Fordham University, and the Amsterdam Houses. Over 7,000 families and 800 businesses were displaced, dispersing what was at the time the country’s densest African American community before Harlem.

What stories are still lost to time, locked underneath these modern buildings? Perhaps excavation could unearth information about the lives and homes of this lost community.

Columbus Avenue - 9th Avenue Elevated Train

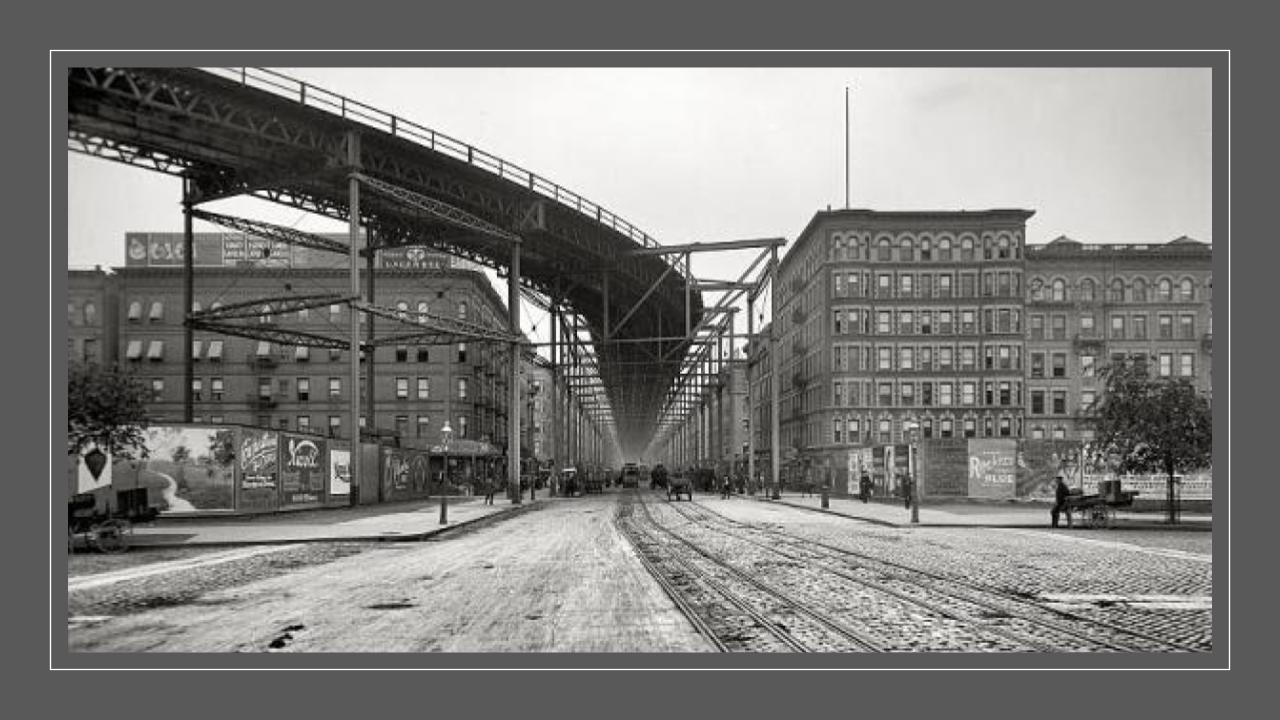

Before the MTA consolidated New York City transit, there was the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. The first public transportation line to reach the Upper West Side was the 9th Avenue Elevated, an above ground train that ran parallel to the storefronts and rooftops of Columbus Avenue. Its ghostly footprints can be seen in vintage photos from a bygone era. Most of the stations in our neighborhood opened in 1879, and development along Columbus was spurred on by its convenient presence.

As both the city’s transit and the city’s urban development expanded uptown through the turn of the century, this pioneering line began to fall out of favor. All of the stations on the UWS were eventually closed for good on June 11, 1940. But what traces do they leave behind? Perhaps we need to go underground to find out…

Park West Village - The Old Community

Today, the area between West 97th and 100th Streets near Central Park West is home to the Park West Apartments. But underneath, odds are traces still exist of the Old Community, a tight-knit Bloack community wiped out as part of one of the first urban renewal projects undertaken by Robert Moses. The community began forming in 1905 when major Black realtor Philip Payton Jr. began leasing properties in this mostly wealthy white neighborhood to Black tenants. Prosperous Black residents in the city arranged a meeting to discuss why African Americans should not live in aristocratic sections of the city, if they could afford it, and thus sparked interest in leasing properties in the Upper 90s. Black tenants paid the same rent as white tenants – around $25-40 a month, and there was no shortage of potential renters.

An enclave of pioneering Black artists resided in this mini neighborhood, many of whose careers were only starting in the early 20th century. Billie Holiday lived at 9 West 99th Street; others included actor Robert Earl Jones, artist Charles Alston who made the bust of Dr. Martin Luther King displayed in the White House, and historian and collector Arturo Schomberg. What evidence of their lives could we find buried today?

Acknowledgements

KPF is made possible by the contributions of current and former Council Members and Borough Presidents Gale Brewer and Mark Levine, as well as the Department of Cultural Affairs (DCLA) and the Ove Arup Foundation. KPF is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. With their support, LANDMARK WEST’s KPF program offers a suite of courses aligned with the NYC Core Curriculum.