Trinity Lutheran Church of Manhattan

164-168 West 100th Street

by Megan Fitzpatrick

The congregation, also known as the German Evangelical Trinity Congregation, was established by a strong community of German-speaking Lutherans in Manhattan Valley in the late 19th century. They endured the hardship of change over the years and a threat to their place of worship. The history of Trinity Lutheran Church is also a history of urban renewal and a successful campaign to preserve an important landmark in the neighborhood.

German migration to Manhattan is a significant chapter in the city’s rich tapestry of immigrant histories. By the mid-19th century, German immigrants had established a notable presence in Manhattan. They settled in neighborhoods such as the Bowery, which became known for its German-American community. Over time, German immigrants began assimilating into the broader New York City population, and real estate speculators, like an individual known as ‘Mr. Russl’, began to open up neighborhoods in Upper Manhattan for German communities. He looked at the Manhattan Valley/Bloomingdale area to develop housing and community buildings for his prospective tenants and believed that a Lutheran Church was the perfect draw.

First established “The German Independent Lutheran Holy Church of Bloomingdale, NY,” the newly formed community rallied to find a pastor and a location. In 1888, resident Edward Dressler enlisted the out-of-work Lutheran clergyman, Pastor Friederich Heinle, and in May of the same year, the congregation gathered for the first time at a store on the corner of Manhattan Avenue and 106th Street. The reason for Pastor Heinle’s unemployment may have come to light all too soon for the congregation as not long after his appointment, he was forced to leave because it was said he was “filled with the wrong spirits.” Whether this means he was suffering from mental health problems or was intoxicated on the job, we will never know.

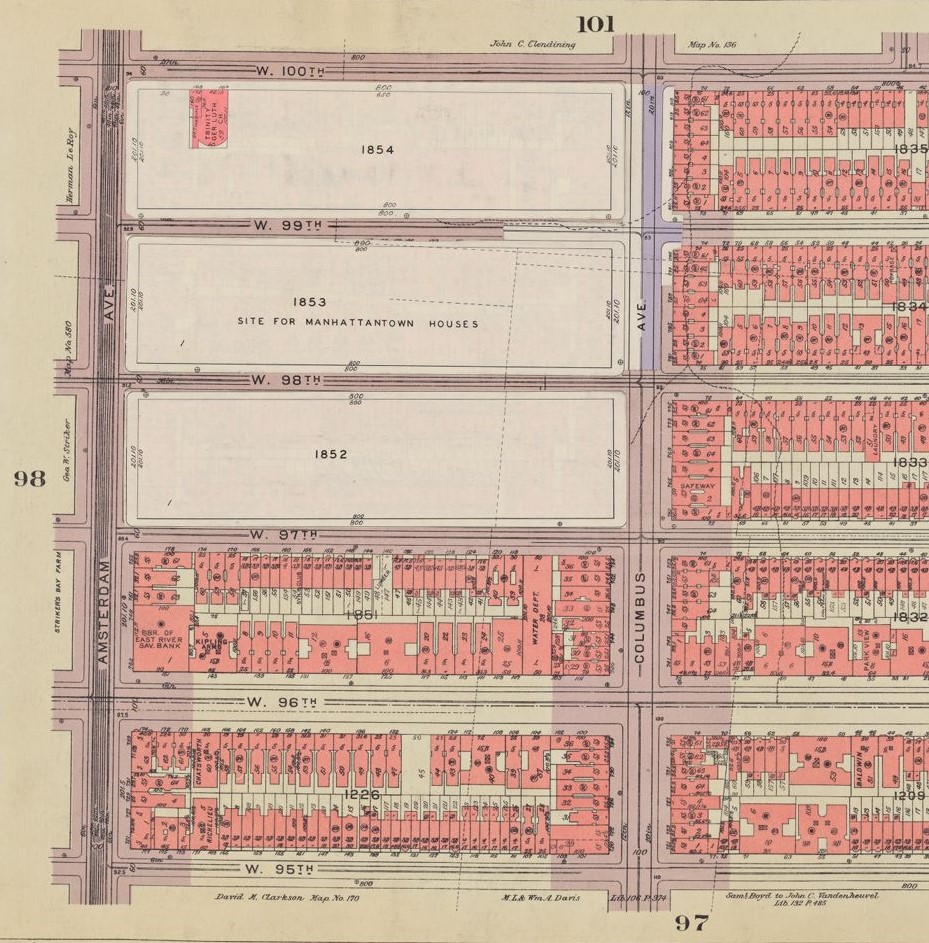

The following year, under new leadership, the congregation was named “The German Evangelical Lutheran Trinity Congregation.” Pastor Carl Reinhold Tappert, father of renowned theologian and professor Theodore Tappert, took the reins. Under Pastor Tappert, the congregation moved once again, a little south to Amsterdam Avenue and 100th and 101st Street. Pastor Tappert wrote about his first impressions of the church when he assumed the leadership role and described it as “discouraging” for several reasons.

My first impressions of my new charge were discouraging, to say the least. For my installation and first church service were conducted in a store. The discharged pastor still lived with his rather large family above the store, and three of his daughters supplied music for the service, one by playing the harmonium and two by standing nearby and singing. Of a congregation, there was little to be seen. The first congregational meeting was a rather stormy affair; it lasted until midnight. Not long afterwards the member of the congregation in whose store the services were held went into bankruptcy and the group had to find a different place for our services. We managed to find a larger store with several rooms (on Amsterdam Ave. between 100th and 101st streets). It was located near a fire-house, and because the horses there attracted flies to the neighborhood, such merchants as butchers, grocers, and bakers would not rent the place. For this reason, we were able to get the store at a small rental—I believe for forty-eight dollars per month.

Prior to building a permanent sanctuary, the congregation still provided for the community and developed a school and a safe space for children in the neighborhood to go. Pastor Tappert described how the neighborhood children would roam “the streets at all hours” because there was no public school in the entire district.

A man, who was our organist, was engaged as a teacher. A woman, trained as a school teacher, and two girls with training in kindergarten instruction were also employed. Soon all the space at our disposal was filled. I myself taught the most advanced class. The instruction in this school was, of course, in English. Oh Saturdays, however, I conducted morning and afternoon sessions of a German School with the help of the organist and one of the teachers. On Sundays, in addition to Sunday School, I held two services, one in the morning and the other in the evening.

Pastor Tappert eventually sought a transfer to another congregation due to the stress. The job, he said, was causing him “excessive exertion.”

His successor, appointed upon Tappert’s recommendation, was Reverend Ernest Brennecke from Brooklyn. After rocky beginnings for the congregation, Brennecke would remain a permanent fixture for sixty years. His first service, on November 10, 1889, was attended by 12 congregants, 5 adults, and 7 children.

It must have taken a lot of grit for those still remaining in the original congregation in 1908 to give their consent to the tearing down of a place of worship so enshrined in their hearts.

Growing with the congregation

The small, yet determined congregation held sermons in German, with one English language sermon a week, to the disbelief and oftentimes ridicule of members of the community and members “of old and rich congregations down-town,” according to Rev. Brennecke, they “spoke quite indignantly about our foolhardiness.” Nevertheless, under Rev. Brennecke, for the first time the congregation secured land to construct a sanctuary. In February 1890, only three months after Brennecke’s installation, the church purchased a plot on the south side of West 100th Street and Amsterdam Avenue for $12,500. At the time, they possessed a total budget of $375 in debts and 27 old hymn books.

The first church was a modest 40-ft wide and made out of brick with a tin roof. Edward Dressler, who was instrumental in establishing the congregation, was named trustee for the building. The architect in charge was Edward L. Angell, who designed many landmarked buildings on the Upper West Side, including the Endicott Hotel. In March 1895, The New York Times remarked that “the simplicity and purity” of the architecture of the church made it “greatly admired.”

After 18 years, the congregation had outgrown its first building, to almost a thousand members and 500 attending Sunday school, according to The New York Times. They agreed to tear down the building and start again. The church archives note that “It must have taken a lot of grit for those still remaining in the original congregation in 1908 to give their consent to the tearing down of a place of worship so enshrined in their hearts.”

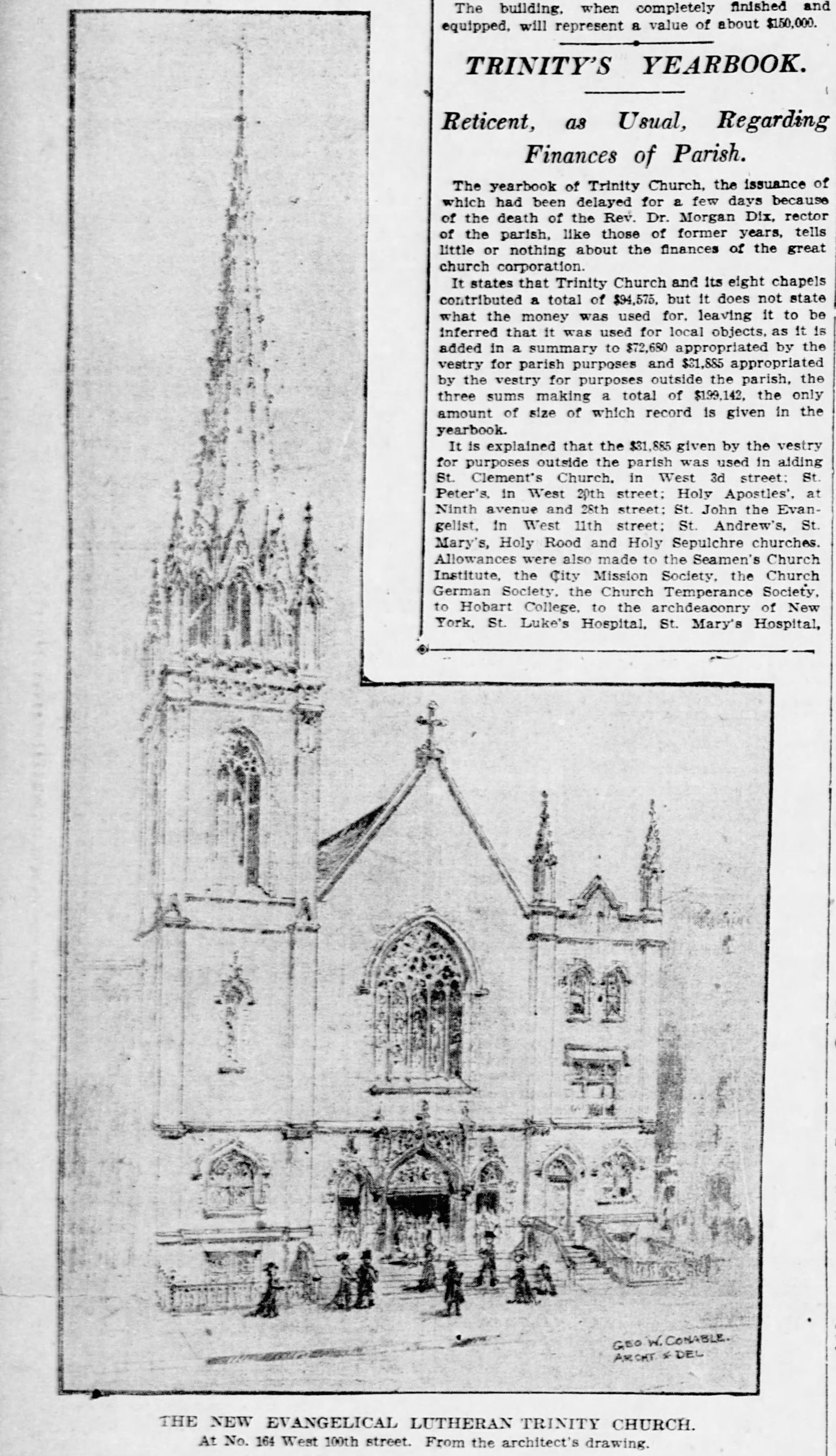

The congregation began to search for a respected and talented architect to design their new and improved edifice. They enlisted American architect George W. Conable. Conable grew up on Conable Avenue, named after his father, in Cortland NY. He studied architecture at Cornell University, graduated in 1890, and moved to Manhattan by 1900. Conable made significant contributions to early 20th-century architecture, including working on the Singer Building with architect Ernest Flagg in 1908, whom he trained under. At the time, it was the tallest building in the world. He also received influential training with C. P. H Gilbert, and the firm of Barney & Chapman.

At the time Trinity was built, Conable was a partner in the architectural firm of Upjohn and Conable, which would last until 1914. Conable designed many Lutheran churches throughout the city. However, George did not forget his roots. He designed the chapel at Cortland Rural Cemetery, the Cortland Democrat Building on Central Avenue, and the Cortland Central School (now the County Office Building).

Conable’s work is characterized by a blend of classical and modernist influences, reflecting the transitional nature of the period. It was no wonder he decided to design the Lutheran Church in the French Transitional Gothic style. The off-centered polygonal steeple and tall crocketed spire, stained glass windows, vertical propositions, and interior adornments are typical of the style. A light brown brick was chosen for the facade, with trimmings of light terra cotta and limestone. A heavily adorned tripartite doorway brings congregants onto broad steps leading up to the main auditorium and down to the Sunday school room.

The interior space of the sanctuary expresses the emphasis on the liturgical requirements of the Lutheran worship service. All of the decorative elements, such as the oak doors, Gothic arcading, the striking ribbed vaulting of the ceiling, and the carved altar are of high-quality design. The larger 60-ft wide church could accommodate 600 congregants and at the time was named “one of the finest of the Lutheran churches” in the city.

The successes of the congregation were expressed through the generous donations of the once small and struggling congregation. Defining features of the newly constructed church were donated by members, including the thirty costly memorial windows. The focal point of the loft, the carved Hutchings-Votey organ, cost $12,000 and was also bought by members.

That success was in large part due to Reverend Brennecke’s work and dedication to the congregation. In just under two decades, the congregation grew enormously, developed two purpose-built churches, and eliminated their debts. Rev. Brennecke declined several tempting calls to large and more established congregations throughout his 60 years of service. He believed “the upbuilding of his congregation” to be his greatest life work.

Urban Renewal

From the 1950s onwards, this area saw a sweep of urban renewal efforts aimed at revitalizing the named Manhattantown region, a 23-acre area of Manhattan running from West 97th Street to West 100th Street. Robert Moses used Title I of the National Housing Act (1949) to replace existing housing and community facilities in Manhattantown that were branded as ‘slum-like’ with the goal of ‘modernizing’ and ‘improving’ living conditions in the neighborhood. The move, like most urban renewal projects in the City, was a controversial one as it meant displacing established communities from their homes and neighborhoods. These communities also challenged the assertion that their neighborhood was “blighted,” particularly when this neighborhood was predominantly Black and Hispanic at the time, according to the 1940 Census.

In 1949, Trinity Lutheran Church received notice that it would be demolished as part of the development plan and replaced with large-scale housing projects, such as the New York Housing Authority’s Frederick Douglass Houses and the mixed income apartment complex, Park West Village. A ten-year campaign ensued to save the church.

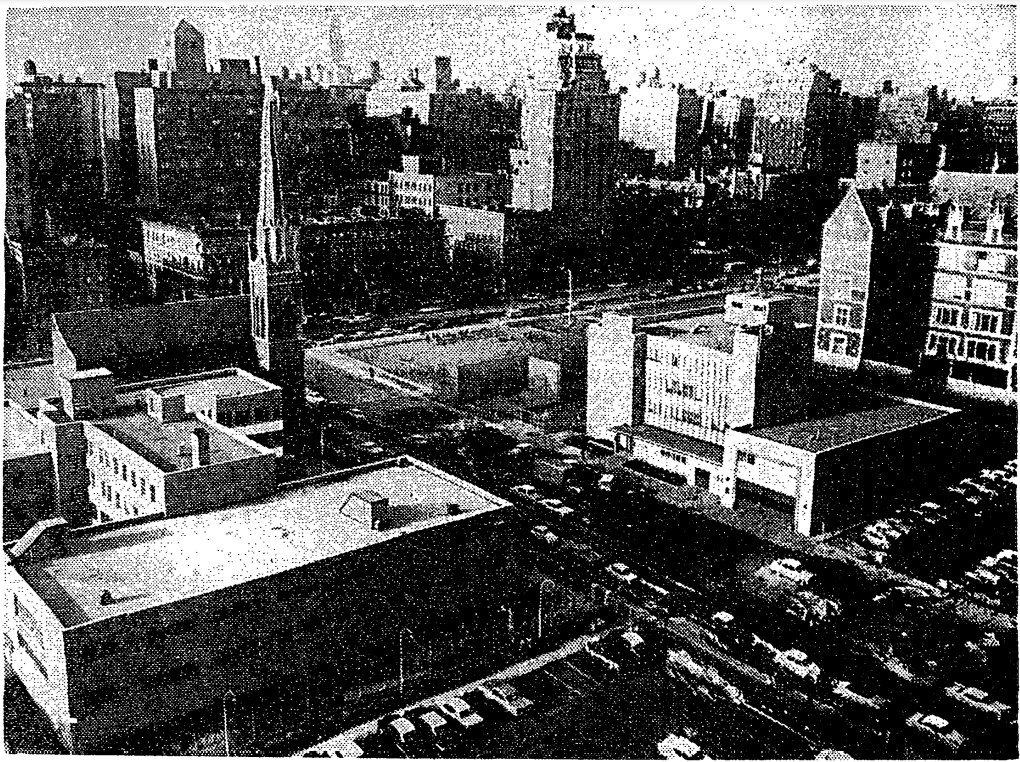

Trinity Lutheran Church survived as the sole building in the area to remain standing after Moses’ development. The survival of the church can be ascribed to the perseverance of the congregation, but also the strong political ties of the Reverend at the time. Rev. Saunders was friends with Henry G. Waltemade, an influential real estate broker on the New York State National Association of Real Estate Boards, and this connection was key in saving the church from the wrecking ball.

In January 1961, after much of the urban renewal development was complete, The New York Times published an article highlighting the new superblocks and their facilities, titled “City Block Given Small Town Air.” It discusses how the decision was made to lump all the community facilities, the library, health center, police station, fire station, and of course the surviving church, together on one block. Although these services had already existed in the area before urban renewal, developers theorized that communities preferred when one could avail of all the services on the same block.

The neighboring library and health facility created a buffer zone between the church and the new shopping center and private parking lot. Its large steeple remained a landmark in the landscape.

A ten-year campaign ensued to save the church

Resilience

The congregation continued to worship in the church during the mass transition and redevelopment going on around them while adapting to the changing neighborhood demographics. From the 1940s onwards, Manhattan Valley saw an increase in migration of Black and Hispanic working-class Americans, many from Puerto Rico. The congregation diversified with the community. German services ceased in the 1930s, due to a greater demand for English, but German still survived in the congregation.

The neighborhood fell on hard times in the 1970s beset by drugs, crime, deterioration, and the abandonment of buildings. However, the neighborhood was also a hotbed for social activism, and Trinity was no exception. Under the leadership of Pastor John Backe, the church utilized its basement as a community space where anti-war and anti-nuclear groups met and planned. Pete Seeger, the American folk singer and activist performed in the church. It held regular meetings of those engaged in the Chilean resistance movement who began calling Trinity, “The Peña Church” (a peña is a community-meeting place, commonly associated with left-wing movements).

In the early 80s, Trinity was one of the first churches in the city to address the AIDS crisis, and through collaborative work, helped develop programs that eventually became a multi-million dollar scatter-site housing system for persons with AIDS in East Harlem. The church currently runs a shelter for LGBTQ youths out of the basement called Trinity Place Shelter.

Construction near the church continued into the 21st-century, and due to the proximity of the construction and because of vibration measurements taken at the church, in 2007; the congregation took the cautionary measure of temporarily removing the original stained glass windows. The recently retired Rev. Heidi Neumark stated, “Although our building was dotted with seismographs, there were many occasions when the vibrations exceeded the legal limits and the construction was temporarily halted as required. We can only assume that some damage has been done. Cracks have sprung up in the parsonage which did not have seismographs.”

Thankfully, in 2023, the scaffolding that surrounded the church for decades was removed and unveiled the return of the original stained glass windows. The facade of this resilient church once again resembles its 1908 appearance.

SOURCES

New York Times, March 10, 1895.

Real Estate Record and Builders’ Guide, July 4, 1908, p. 17.

New York Times, May 16, 1908.

New York Times, January 15, 1961.

National Register of Historic Places, Trinity Lutheran Church of Manhattan, New York County, New York, # 09000722.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Preservation and Research Director at LANDMARK WEST!

Building Database

Be a part of history!

Learn more about Trinity Lutheran Church of Manhattan: