The Self-Congratulatory Prague

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

John G. Prague was among the most prolific real estate developers of the Upper West Side in the 1880’s and ’90’s, most often acting as his own architect. In 1888, he started construction on two mirror image apartment buildings that would engulf the eastern blockfront of Columbus Avenue between 86th and 87th Street.

The twin buildings were completed in 1889. Prague gave the northernmost structure the self-congratulatory name The Prague. Faced in variegated ironspot brick, the five-story structure was a toned-down take on the Romanesque Revival style. While the residential entrance at 72 West 87th Street reflected the expected, heavy medieval influence of the style, the upper floors were devoid of its often-ponderous elements. Prague further softened the design by rounding the corners. Instead of a cornice, the building was crowned by a brick parapet.

There were two apartments of seven rooms on each floor. The stores that lined Columbus Avenue filled with a variety of tenants. The southern store held a Post Office branch, Charles W. Bernson & Co’s bicycle shop was in 553 Columbus Avenue, and E. L. Foghill opened his real estate office in 555 Columbus. The 1891 History and Commerce of New York called Foghill, “a real estate broker in deservedly high repute, whose eligible office is at the Prague Building.”

High repute or not, Foghill was gone within the year when his space became home to Fuchs & Wilkinson, purveyors of “interior decorations and fine furniture.” An article in The Jewish Messenger on April 24, 1891 said that the “lately established” store offered, “a complete and choice stock of all kinds of furniture and paper hangings, and are prepared to fill all orders from a single article to the furnishing and decorating of an entire house.”

The apartments filled with well-to-do professionals. Among them were Dr. Edwin F. Hitchcock and his wife, Sarah; banker Charles G. Wolff and his wife; and the family of economist William Belden Scott.

Scott and his wife had married in 1890. He was close friends with Henry George, who originated the concept of the single-tax movement, and was the former editor of George’s Standard. The Journal said that Scott “had an ample fortune” and “devoted his life to the single tax movement.”

Although Scott was enjoying professional success and, according to The Journal, his “domestic relations were most pleasant and happy,” the 32-year-old was suffering severe depression early in 1896. He agreed to being placed in the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum for treatment. Before those steps were taken, he had a lecture on the single tax scheduled for the evening of February 25. That morning, “shortly before the breakfast hour he eluded his family and his attendant and wandered away,” reported The Journal.

Mrs. Catherine J. Adams had been poisoned when she took a medicinal seltzer powder that had been laced with cyanide or mercury. The intended victim was her cousin, Harry Seymour Cornish, who had been targeted by the wealthy Roland Molineux.

Later that morning Willian Norton, the watchman of a wagon and truck yard, and a truckman, Thomas Burns, heard a shot. They ran to the yard where they found Scott. The Journal graphically reported that he “had fired a bullet through his head, and the ground and fence was spattered with his blood.”

Charles G. Wolff was a native of Laguaya, Venezuela. He had been educated in New York and Brussels and by the time he and his family moved into The Prague he was the senior member of the banking firm Charles G. Wolff & Co.

Dr. Edwin F. Hitchcock had graduated from the Long Island College Hospital of Brooklyn in March 1894. He had been clinical assistant in gynecology at the Columbus Hospital on East 20th Street, but now had a private practice in his apartment. At 9:35 on the morning of December 28, 1898, the hall boy from 61 West 86th Street banged on his door with an urgent call that would make Hitchcock’s name a household name across the country.

Mrs. Catherine J. Adams had been poisoned when she took a medicinal seltzer powder that had been laced with cyanide or mercury. The intended victim was her cousin, Harry Seymour Cornish, who had been targeted by the wealthy Roland Molineux. Cornish was the athletic director of the Knickerbocker Athletic Club where Molineux was a member. After the two became embroiled in a feud, Molineux mailed a bottle of the poison-laced seltzer to Cornish’s attention. But on December 28 when his 62-year-old cousin had a bad headache, Cornish mixed the bromo-seltzer with water and gave it to her. She died shortly after Dr. Hitchcock arrived to her door at 243 West 72nd Street. Every word of his testimony at the sensational murder trial appeared in newspapers for months.

Living in The Prague at the turn of the century was the family of Police Lieutenant Colonel Nathaniel B. Thurston. At least one journalist knocked on his door on the morning of December 17, 1901 hoping to get inside information on Thurston’s rumored promotion. He “was just donning a big befrogged military coat preparatory to going downtown when he was seen in his apartments, at No. 72 West eighty-seventh street, to-day,” said the article in The Evening Telegram. Thurston told him “Officially I know nothing about the appointment as yet.” In fact, everyone knew that his promotion to Deputy Commissioner was all but a done deal.

The policemen grumbled at their bad luck, “but they did not consider the incident at all important until two days later,” said The Sun, “when the news of Col. Thurston’s appointment reached them. Since then, they have not known what peace or happiness means.” The article concluded, “The problem that disturbs them is: Did Col. Thurston see them well enough to recognize them after Jan 1?” (New Year’s Day is when Thurston’s promotion to Deputy Commissioner took effect.)

At the time, the rent for a seven-room apartment with bath was $45 (about $1,400 today). It came with “hall service,” meaning that uniformed hall boys were available to run errands, bring up mail and packages and other tasks.

Following Dr. William Hitchcock’s death, Sarah remained in their apartment until her death on January 30, 1905. Her funeral was held in the apartment two days later.

By that time another well-respected doctor, Thomas Wood Hastings, had lived in The Prague for at least three years. His apparently busy schedule included being assistant instructor in clinical pathology at Cornell University Medical College, first assistant in the Medical clinic of the Cooper Medical Dispensary and Visiting Physician for the Pacific Hebrew Orphan Asylum.

When Middletown, New Jersey resident A. Leonard Seaman went on the lam in 1910, his wife and two small children fled to New York and took an apartment in The Prague. Seaman was a member of a fraternal lodge with, by today’s viewpoint, the unthinkable name of the Improved Order of Red Men. He served as the treasurer of his branch, Umpqua Tribe No. 331. But in January 1910 the lodge discovered that he had embezzled $2,500 (closer to $70,000 today) and filed a warrant for his arrest.

At the time, the rent for a seven-room apartment with bath was $45 (about $1,400 today). It came with “hall service,” meaning that uniformed hall boys were available to run errands, bring up mail and packages and other tasks.

Police were able to track down his wife because “with remarkable pluck” she had started a subscription paper—the equivalent of a go-fund-me page today—to raise funds to repay the money. A detective was assigned to trail her and on March 25 the Tri-States Union reported “Seaman was arrested in New York at a flat occupied by his wife and two small children at 72 West 87th street. The detectives have been watching that place for a week.”

In 1913 the stores at 551 and 553 Columbus Avenue were combined to accommodate the Nauheim Pharmacy. Hoffman & Elias, electrical contractors, were now in the former Post Office space at 549. They would remain well into the 1920’s.

French-born Emile George Michel Sigrist and his family lived in the building at the time. He had come to the United States from Les Vosges, France, around 1867 with his father, Michel Sigrist, and four sisters. When Michel Sigrist went back to France, he left a large amount of real estate, mostly in Harlen, to his children. Emile died at the age of 63 in his apartment on November 30, 1914. The family continued to reside there, and in 1917, son Emil and his wife, Josephine occupied the flat.

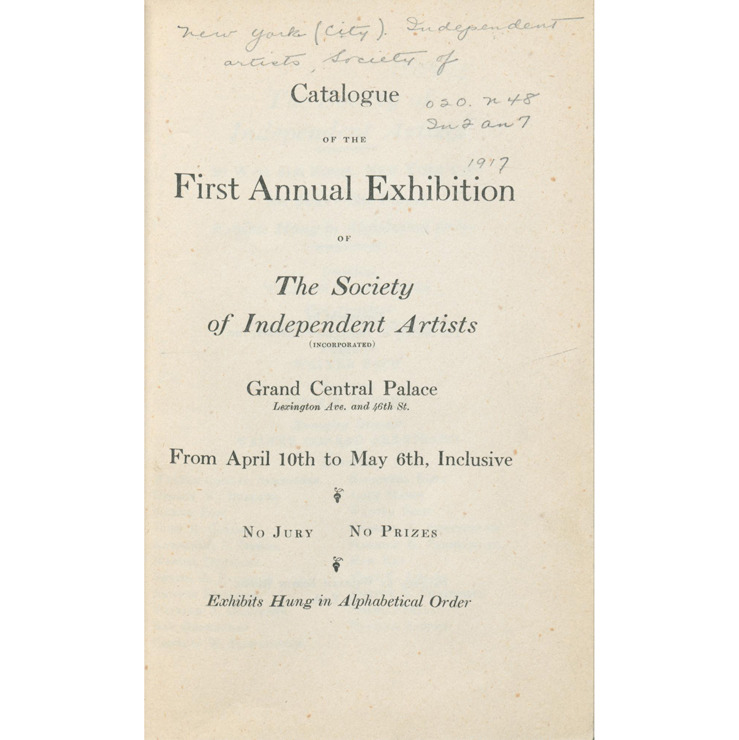

George Pearse Ennis and his wife, Georgia Leaycraft Ennis lived in the building by 1917. Both were artists and George’s works were shown at the Society of Independent Artists Exhibition in the Grand Central Palace at Lexington and 46th Street that year. The pair would remain at The Prague for several years.

In 1946 the G & L Antiques Shop opened in 549. It advertised “Beautiful antiques and old silks.” As the Columbus Avenue neighborhood changed, so did the commercial tenants. That space was home to the Strycker’s Bay Neighborhood Council office by 1963, and to the Nipa Candy & Grocery store in 2002.

In the 1970’s the Parkview market operated from 555 Columbus Avenue. New York magazine described it on February 10, 1975 “a battered fortress tattooed with graffiti and papered with demands for a free Puerto Rico.”

That dismal condition along the avenue changed with the dawn of the 21st century. The combined stores at 553 and 555 are home today to the PlantShed Café, where coffee can be had with a side of potted fern; the massage and acupuncture clinic Akai Wellness Center occupies 549 Columbus Avenue.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

549-555 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 549-555 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Jennifer Simoni!

Meet Ilya Suylov!