The Champs of the Beauchamp

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

Prolific architect John G. Prague most often designed buildings for which was also the owner and developer. But in 1894, he was hired by another real estate operator, Adam E. Fischer, to design a group of five buildings at Columbus Avenue and 85th Street.

The corner building would be a five-story “flat and store” structure called The Beauchamp. Its residential entrance was placed on the side street, at 78 West 85th Street. Prague faced the upper stories in beige brick trimmed in limestone. His romantic take on the Romanesque Revival style included grouped, engaged columns and medieval-style carvings on the Columbus Avenue façade, and an arched entrance on 85th Street supported by squat columns with intricately carved capitals.

The apartments, two per floor, ranged from seven to eight rooms with a bath. An advertisement in 1897 boasted “hardwood, elevator, hall boys.” Both the elevator and the presence of hall boys were upscale amenities in the 1890’s—the uniformed hall boys on hand to deliver mail and packages, run errands, and do other tasks as needed.

Among the tenants in 1897 was famed violinist Edouard Remenyi. Born in Hungary, he became a friend of Johannes Brahms while living in Germany. It was Remenyi who introduced the composer to Hungarian music.

The residents of The Beauchamp had one or two servants. In July 1897 Remenyi and his wife hired Pieras Englander, described by The Morning Times as “a handsome young Hungarian maid.” While she lived in the apartment, the young woman’s husband (who was a waiter) was permitted to visit her regularly.

On September 1, 1897 Pieras suddenly disappeared and upon investigation it was discovered she had run away with jewelry and other items worth nearly $320,000 in today’s money.

She did not get far. The following day The Morning Times reported, “The pretty thief was captured late last night and nearly all of the stolen property was recovered.” It turned out that each time her husband visited, Pieras would slip him something of value. Trunks found in the couple’s apartment on Avenue C held the stolen property. The Morning Times said, “When it was displayed in the West Sixty-eighth street station this morning the room looked like a lavishly furnished booth in a fashionable bazaar. The finest of silk and satin dresses, gems and silverware were scattered in profusion around the station.”

At the time, the office of architect Austin Hays was in the storefront at 517 Columbus Avenue and the cigar store of Cuban immigrant Alphonso Cardrera was in 509 Columbus Avenue.

In February 1897, 19-year-old Acasto Granleo escaped from a Spanish prison in Cuba and made his way to New York City. Cardrera gave him a job in the cigar store and allowed him to sleep in the back room. Something, however, still weighed heavily on the youth’s mind.

The Morning Times said, “When it was displayed in the West Sixty-eighth street station this morning the room looked like a lavishly furnished booth in a fashionable bazaar. The finest of silk and satin dresses, gems and silverware were scattered in profusion around the station.”

John Snoot ran a tailor shop next door and eight months later, early on the morning of October 14, he detected the strong odor of gas. He found Police Officer Schomberg who broke into the store. There he found Granleo unconscious on his bed. He had opened all the gas jets in an attempt to commit suicide. The New York Herald reported, “He did not succeed in killing himself, and is in Roosevelt Hospital, much disappointed. He refuses to say why he made the attempt.” Doctors said that “the great height of the ceiling of the room in which he slept,” had prevented his death.

Mary P. Watrous was more successful two years later. The 25-year-old had arrived in New York in December 1898 with a “friend,” Oliver H. P. Noyes. Noyes boarded with a family on West 10th Street and Mary subleased the Beauchamp apartment of Mrs. Evangelides, who was on an extended stay in Bermuda. Mary retained the services of Mrs. Evangelides’s servants, as well (who oddly enough, referred to her as “Mrs. Allen”).

The relationship between Mary and Noyes appears to have been more than platonic. He told officials later that she lived “on his income.” He was visiting on the night of February 3 when at around 10:30 Mary asked him to go to the icebox and get her a glass of water. When he returned she said, “I’ve taken it.” What she had taken was oxalic acid, a compound intended for cleaning purposes, like rust removal.

The maid rushed to the office of Dr. S. H. Dillingham, next door at 76 West 85th Street, telling him that her mistress “had taken something which made her very ill.” Dillingham went to the Watrous apartment with a portable stomach pump. He called in a second doctor to help. The New York Times said, “they worked over the then insensible woman until 8 o’clock in the morning, when she died.”

No one could come up with a reason that the young woman had taken her life. The mystery was neatly wrapped up when her doctors declared simply that Mary “was insane when she killed herself.”

Like Edouard Remenyi, Franz P. Kaltenborn was a well-known violinist. Born in Homburg, Germany in 1865, he came to New York at the age of 6. In 1896, he formed the Kaltenborn-Beyer-Hane String Quartet, which The New York Times said, “was so well received by some of the most critical audiences here.”

In 1892, while he was still comparatively unknown, he and Lulu Borman fell in love. Lulu was the daughter of stockbroker Adolph H. Borman and the young couple married “against her parents’ wishes,” according to The New York Times. Lulu took the position of her husband’s manager and then of the quartet. As their fame and financial prosperity grew, the Kaltenborns took an apartment in The Beauchamp.

But by the summer of 1900 storm clouds were forming over the Kaltenborn household. And when Kaltenborn announced a series of Sunday concerts at the Herald Square Theatre for that fall, it was noted they would be “under entirely different management.” Things worsened to the point that on January 13, 1901 while Lulu was out of the apartment, Keltenborn packed his things and moved into his father’s house on East 19th Street.

The domestic troubles lapsed into the professional. On January 15, The New York Times reported “Lovers of good music will find much cause for regret in the following letter:

To the Editor of The New York Times:

Will you kindly insert in your columns at the earliest date the following:

Owing to Mr. Kaltenborn’s desertion of his wife, we, the undersigned, have decided to discontinue our work with him, and to reorganize our quartet.

The couple’s dirty laundry was aired again a month later. A suspicious Kaltenborn followed his wife to Philadelphia where he surprised her and Carl Hugo Engel, a former member of his quartet, in a room at the Bingham House. Lulu insisted that the two were conducting a “business meeting.” Kaltenborn’s sister told a reporter “Of course it is only natural to suppose that, after what has occurred, he would appear to the courts to be freed from his wife. Any man would do likewise.”

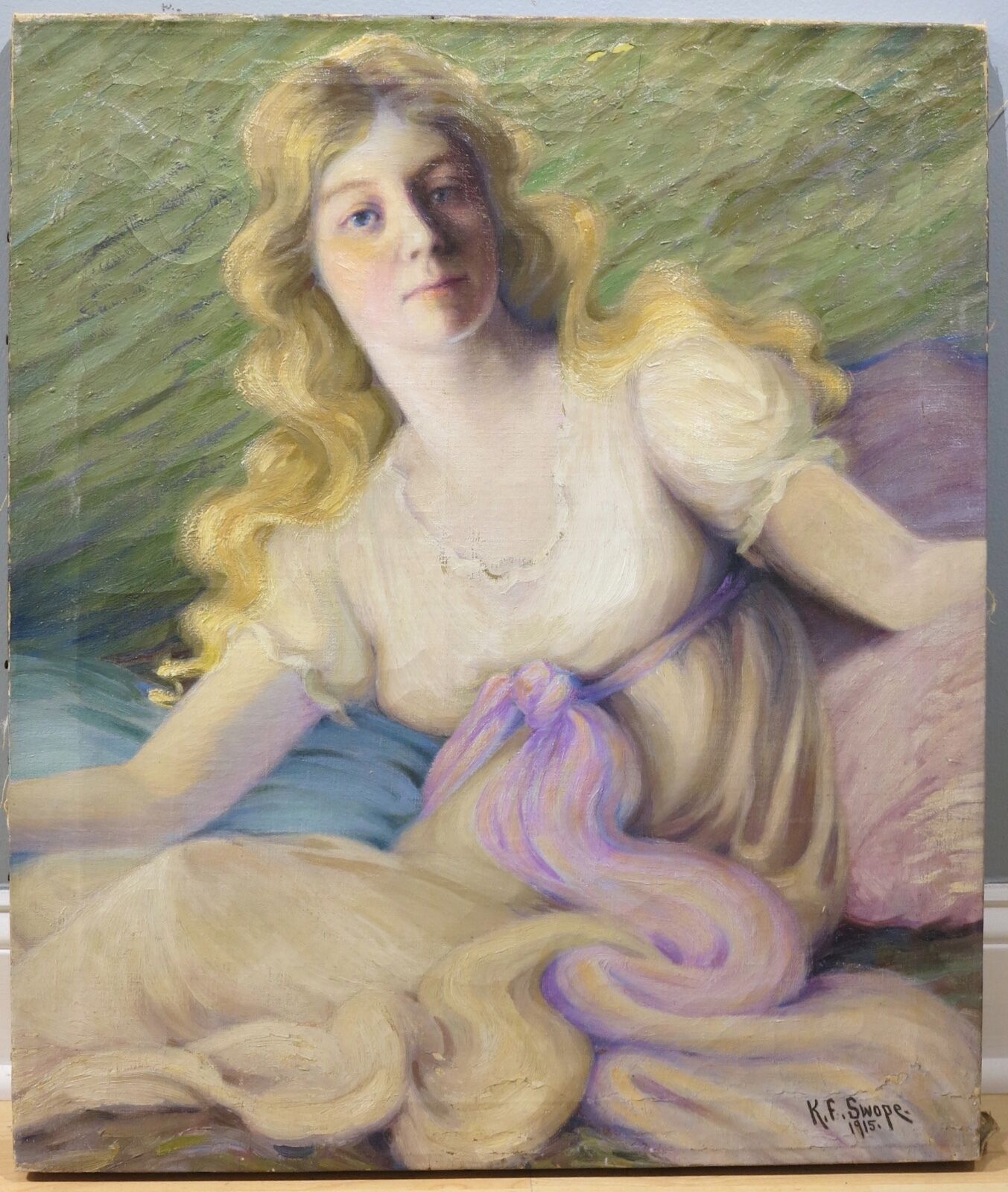

At the time of the Kaltenborns’ messy affair, Herr Glasenapp was living in the building, as were Charlton Armstrong Swope and his wife, Kate.

Glasenapp’s title in 1900 was “Royal Prussian Machine Expert” and he was working in New York as an inspector of railway construction. By 1903 he held the position of Technical Attaché with the German Consulate.

Charlton Swope was a travel-freight agent for the Louisville & Nashville Railroad. Both his brother, H. Vance Swope and his wife were artists. Kate Swope, who was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1868, had received many awards for her works, including the Gold Medal in 1895 from the Southern States Art League.

On the evening of November 9, 1902 two residents, Mrs. Winsom Waring and Walter M. Smith, went to dinner at the Claremont Inn overlooking the Hudson River. For some reason, possibly for the sake of propriety, they drove separately–each taking a one-horse runabout. After dinner they headed home down Riverside Drive, neither of them thinking to light their carriage lamps.

At around 8:30 Policeman McLaughlin noticed them and called out for them to light their lamps. Describing Mrs. Waring as “a fashionably attired woman,” the New York Herald reported that she “replied to his demand that she light the lamp of her runabout by slashing him over the head with a whip.” Both Mrs. Waring and Smith were arrested. The New York Herald said, “Mrs. Waring denounced the arrest as an outrage.”

After sitting in the station house for an hour and a half, awaiting someone to bring bail, they climbed back in their respective carriages and headed home. “This time with their lamps lighted,” said the newspaper.

By now the store at 515 Columbus Avenue was home to the H. B. DeVoe plumbing business, owned by Harkness B. DeVoe. His was a substantial contracting firm, responsible, for instance, for plumbing the magnificent Morton Plant mansion at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street (home to Cartier jewelers, today). Store windows of a plumbing business customarily would garner little attention from passersby, but that was not the case with H. B. DeVoe.

A branch of the Gallagher Stores was in 511 Columbus by 1902. The chain operated 18 wine stores throughout Manhattan. An advertisement that year announced a sale of “High-Grade Wines” including a Claret at 23 cents per bottle and a Riesling of “excellent quality, fully matured,” at 33 cents.

In 1904 The Plumbers’ Trade Journal noted:

B. Devoe, of 515 Columbus avenue, Manhattan, has one of the finest shops along the line. One of his windows contains a line of enamel ware; the other has a display somewhat out of the ordinary. It consists of a large zinc pan the size of the window in which he places all crawling and creeping things which he may take out of supply pipes. Up to the present time he has a couple of eels, a small tortoise, a number of wriggly things which he doesn’t name, and last, but not least, a small alligator. These animals all live quietly and amicably together under the shade of a number of tropical plants, which grow in imitation of a miniature tropical scene around the edge of the pond in the sand and gravel.

A branch of the Gallagher Stores was in 511 Columbus by 1902. The chain operated 18 wine stores throughout Manhattan. An advertisement that year announced a sale of “High-Grade Wines” including a Claret at 23 cents per bottle and a Riesling of “excellent quality, fully matured,” at 33 cents.

Loren Murchison brought press attention to The Beauchamp in 1920 when he earned a place on the U. S. Olympic Track and Field team. Born in 1898 in Farmersville, Texas, he would become known as one of the finest Olympic sprinters of his time. He won a gold medal in the 100-Metre Relay that year and would win a second gold medal in the same category in the 1924 Olympics. Tragically, in 1925 he developed spinal meningitis and was paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of his life.

In the 1920’s a restaurant occupied 511 Columbus Avenue and the Zieger Pharmacy was in 517. On April 28, 1928, the counterman at the restaurant, John Montakas, faced the barrels of guns held by two robbers. They made off with $50 from the cash register and escaped in a taxi. The same thing happened the following year, on January 22, 1929, at the Zieger Pharmacy. Two men walked in that night and asked Morris Mendelsohn for a porous plaster, according to The New York Sun. “when he turned his back the pair produced revolvers and forced him into the back room. Then they rifled the cash register, taking $150.”

The tradition of artists living in the apartments continued in the early 1930’s when Minna R. Harkavy’s doubled as her studio. Born in Estonia in 1887, she had come to the United States around 1900. She was a founding member of the Sculptors Guild and of the New York Society of Women Artists. While living here she exhibited a bust of Hall Johnson in the Museum of Western Art in Moscow and the piece was purchased by the Pushkin Museum.

The Beauchamp was renovated in 1975, resulting in five apartments per floor. Around 1980, Panarella’s Tuscan restaurant opened in 513, its dining room described by New York magazine in 1992 as “a charming, romantic setting.” In December 1990, Panarella’s opened a store next door at 515 Columbus Avenue, Cucina Rustica. It was described by The New York Times food critic Florence Fabricant as “a charmingly cluttered food shop”

Jackson Hole opened in 517 Columbus Avenue around the same time. Specializing in burgers, despite a less than enthusiastic review from food critic Eric Asimon in March 1994, it remained in the space until at least 2002.

The row of stores was condensed to just two in the first decade of the 21st century. The wine bar Osteria Cotta opened in the southern space in 2011 and remains there today. In 2014 Machiavelli Italian restaurant opened in 519, replaced by Viand Café in 2017.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

509-517 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 509-517 Columbus Avenue: