New York, Paris, Mars…

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

In 1887 real estate developers Kennedy & Dunn completed construction on two mirror image flat (or apartment) buildings at the northeast corner of Columbus Avenue and West 84th Street. Designed by the architectural firm of Thom & Wilson in the Renaissance Revival style, they were five stories tall and faced in red brick. Intricate terra cotta panels decorated the façade and limestone pediments crowned several of the windows. The buildings shared a pressed metal cornice.

The residential entrances were at 57 and 59 West 84th Street. On the Columbus Avenue side were two stores. Each of the apartments contained six rooms and a bath. An advertisement touted them as “highly decorated,” referring to details like the tile and woodwork. Residents, who enjoyed amenities like steam heat and hall boy services, paid between $30 and $50 per month rent—equal to about $880 today for the least expensive.

The corner shop became the grocery store of German immigrant Joseph H. Weismir, while the space at 503 Columbus Avenue was leased to C. Jolly & Son, a “scouring and dyeing establishment.” It would be one of four locations of the firm which The Evening World described as “one of the oldest in the dyeing business in this city.” The newspaper also noted “Nearly all the employees [are] French people.”

The residents were professional and financially comfortable. The widow Etta Brewer, whom the New York Herald described as “a stylishly dressed young woman,” moved in during the summer of 1895. Only a few months earlier she had been the victim of a horrifying crime.

That May she had gone to the theater with a man and afterward to dinner. While at the restaurant, she later told police, “he induced her to drink something—what she could not say.” Afterward he took her home. When she woke up the following morning, she had no recollection of anything that had transpired after sitting down to dinner, but quickly realized that her six diamond rings were gone. Her fingers were cut from his prying the rings off. She was also missing her pair of diamond earrings, a gold chain, a diamond pin, and $25 cash—in all about $95,000 in items by today’s valuation.

When she woke up the following morning, she had no recollection of anything that had transpired after sitting down to dinner, but quickly realized that her six diamond rings were gone. Her fingers were cut from his prying the rings off.

Six months later, on the evening of November 3, she was walking along Broadway with two friends when she recognized Thomas O’Connor. Suddenly, according to the New York Herald, she “darted” from them, grabbed the collar of a man, and began shouting “Police! Police! Help!” The refined young widow was not above creating a scene. The newspaper said, “Although the young man struggled to escape from his captor, she clung to him and her cries rang out so that they could have been heard a block away.”

At the station house, O’Connor pleaded his innocence and the New York Herald tended to believe him, it seems. It ended its article saying, “the prisoner has the appearance of a clerk and does not look like a criminal who would drug and rob a woman, and Mrs. Brewer says that is the way he deceived her.”

Living here the time were the adult children of John J. Williams and his wife, both deceased. Williams had worked for Tiffany & Co. for many years. Sharing an apartment were Minetta, Ellen J., and their brother, who went by his initials, O. J.

The first to marry was Minetta. On October 31, 1896, The Evening Telegram reported, “The formal engagement will soon be announced of Miss Minetta, youngest daughter of the late John J. Williams, No. 57 West Eighty-fourth street, to Frank Bishop Appleby.” Two years later plans were being made for O. J.’s wedding to Nellie Pierce when, in January 1898, Ellen fell ill. Her condition worsened to pneumonia and she died on February 12. Her funeral was held in the apartment two days later.

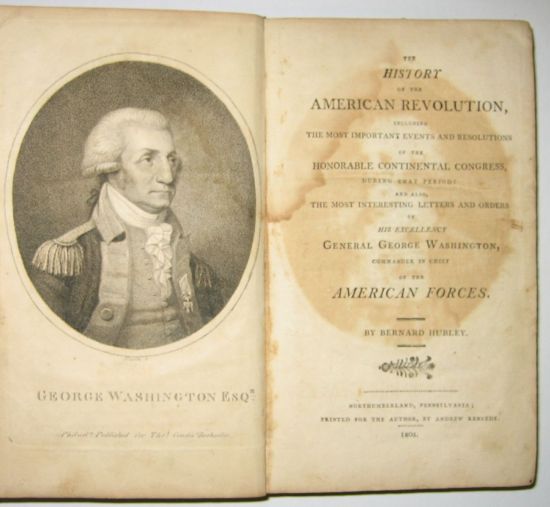

A prominent couple living here at the time were corporate attorney Jesse Larrabee and his wife. Mrs. Larrabee was a member of several women’s clubs, including the Daughters of the American Revolution. A resident with an equally impressive American background was Elizabeth McCalla Stephan, whose grandfather, Captain Bernard Hubley, had written the History of the American Revolution within 25 years of the country’s independence. Among his papers which Elizabeth owned was a letter from George Washington to John Hancock dated July 14, 1775 discussing the Battle of Charlestown.

Harry Wilburn Baldwin and his wife lived in the building by 1897. In 1895, he had been appointed assistant to the Commissioner of Jurors in the Fifth District Municipal Court and in 1908 was promoted to chief clerk. He still held that position when he died in his apartment here in 1921.

In the meantime, at the turn of the century the grocery store was being operated by another German, Charles Krumind. In 1902, he received permission to place a fruit stand on the sidewalk. By then the space next door had been the stationery and news store of David Murdoch for at least four years.

Artistic types began to rent apartments around this time. Among them was pianist Adelaide C. Okell whose apartment doubled as the studio where she taught and where the recitals of her students were held. On January 19, 1902, the New-York Tribune reported, “Miss Adelaide C. Okell will give a musical and reception to her pupils and their friends at her studio, No. 57 West Eighty-fourth-st., on Wednesday at 4 o’clock.”

Another resident involved in the arts was actor Donald Gallaher. On February 26, 1904, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Gallaher was starring in the Little Princess. He was just nine years old and had been acting for three years. The newspaper reported his income at $65 per week (about $23,200 per year today) and that he “attends private school while in New York.” The article added that he “has permission to act under the Gerry law.” (That was an early form of child labor regulations.)

The German grocery and the stationery store would continue in their spaces under changing ownerships. By 1910 Charles Krumwiede ran the grocery and Simon A. Garson operated the stationery and news store.

German changed to Italian when Antonio Aversa took over the grocery, now called the Vermont Market, in the mid-1920’s. He and his family conveniently lived in an apartment upstairs. More than a decade later, on March 14, 1937, The New York Times reported that around 1:00 on the previous afternoon, “Antonio Aversa, selling a bunch of asparagus in a market at the corner of Columbus Avenue, saw smoke and turned in an alarm.” The fire was in his building.

“Mrs. Holm, getting back to lunch, said climbing down the ladder had been ‘fine’ and her husband, snug in a heavy overcoat, conceded that the experience was worthwhile at 82 because ‘you have to try everything.’”

Upstairs the Holm family were just sitting down to lunch. Hans Holm was 82 years old, his wife, Marie was 74, and their son, Edward was 30. Edward later told a reporter, “We were just about to eat, and we heard the fire engines…I ran out in the hall, it was full of smoke, so I put my father in here,” and he pointed to a bedroom. There he dressed his father and headed down the stairs with him. At the second floor the fire fighters took control of him. Edward ran back into the apartment for the family’s pet cat, Minnie. In the meantime, his mother had clambered out the window and down a fire ladder to the street.

In all 16 families—between 40 and 50 residents plus Minnie and a “mongrel dog” named Nellie—were rescued. The New York Times reported, “The rear court was littered with blackened chairs, mattresses and a toy automobile.” But the elderly Holm couple seemed unphased by the excitement. The article said, “Mrs. Holm, getting back to lunch, said climbing down the ladder had been ‘fine’ and her husband, snug in a heavy overcoat, conceded that the experience was worthwhile at 82 because ‘you have to try everything.’”

In 1965, the two buildings were combined and the entrance at 59 West 84th Street was bricked up. Two more commercial spaces were carved into the 84th Street side at the time.

By the early 1980’s Lucy’s Bar was in 503. In its July 1, 1985 issue New York Magazine wrote that although “New York, Paris, Mars” was printed on the awning, “inside it’s Southern California all the way.” And next door, the space continued the century-long tradition of a grocery as the Parisian Deli, operated by Korean immigrants.

The Parisian Deli had granted credit to a local, Constant Casimer, who lived nearby at 66 West 84th Street. But, as the end of 1986 neared, the owner rescinded the privilege. At around 1:00 on the morning of November 30 Casimer walked in and asked for a pack of cigarettes on credit. The clerk, Heung Un Lee, a 38-year-old newly arrived immigrant from Korea, refused. About two hours later Casimer returned with a knife and stabbed Lee to death. Today, it is New Parisian Deli.

In April 1996, the bar-restaurant Prohibition opened in the space formerly home to Lucy’s Bar. On January 9, 2020, the West Side Rag noted, “The bar quickly became a neighborhood fixture known for its live music, warm environment, and good food.”

After more than 130 years, the now-combined buildings have suffered more than their share of abuse. The cornice was removed years ago, and the ground floor has been brutally disfigured. And yet, close inspection reveals Thom & Wilson’s charming details still hiding in plain sight.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

501-503 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 501-503 Columbus Avenue / 57 West 84th Street: