Sing Sing, City Prison, or Direct Release

by Tom Miller, for The Cultural Immigrant Initiative

John F. Dunker was furiously erecting flat (or apartment) houses in the developing Upper West Side during the last quarter of the 19th century. In May 1884 he purchased “for improvement” the three vacant lots at the southwest corner of Ninth Avenue (later Columbus Avenue) and 83rd Street, paying the equivalent of just over half a million in today’s dollars. He hired architect Jacob H. Valentine to design three apartment buildings with stores on the site.

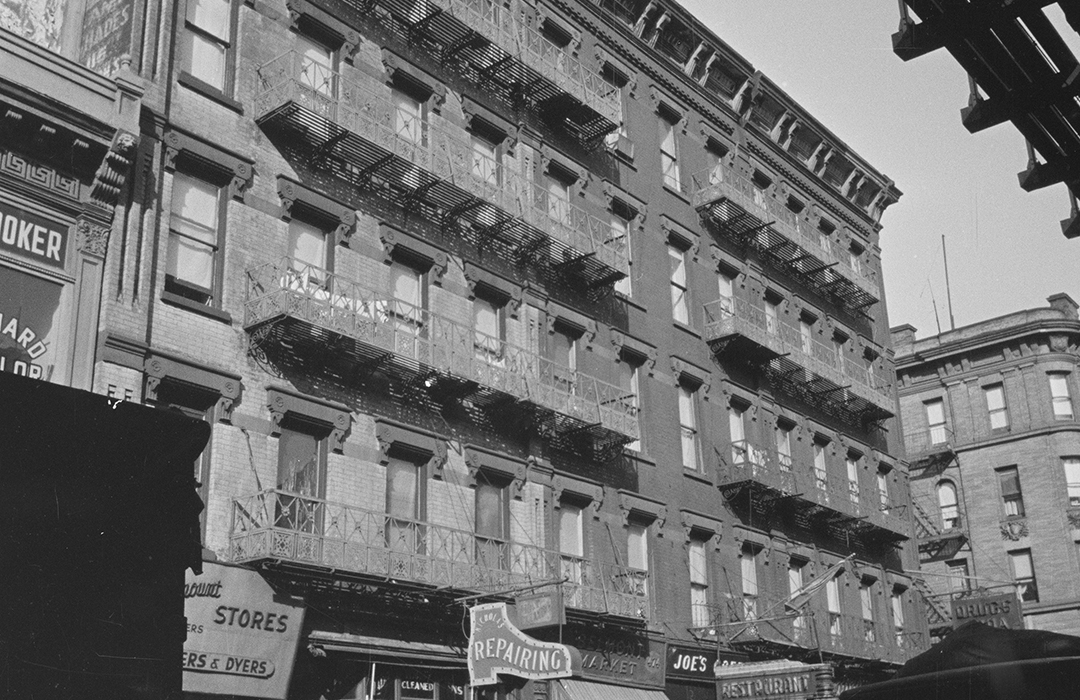

Completed the following year, each building cost the equivalent of $500,000 today to construct. Faced in red brick and trimmed in brownstone, their neo-Grec design featured geometric lintels with incised flowers. Rows of recessed brick created the suggestion of fluting to the brownstone-capped piers at each floor that separated the buildings. The residential entrance of the southernmost building was around the corner at 101 West 83rd Street.

Among the early residents of that building were James Burgess (described by The Evening World as “a burly West Indian) and his wife. A clerk with the Lehigh and Wyoming Coal Company, his heinous actions brought unwanted publicity to the address. In December 1888 the 47-year-old was charmed by a 13-year-old schoolgirl, Gracie Irwin, who was selling tickets to a church fair. He began what today would be recognized as the actions of a predator.

Gracie later explained, “He never said anything very naughty. He used to say it was a shame that I had not more enjoyment in my life, and frequently assured me that some day he would take me away forever and get me a nice little flat.”

Police across the city searched for what was believed to be the kidnapped girl. Then, two days later, Gracie sent a telegram to her aunt and guardian, Caroline Smith at 312 West 84th Street that read simply, “Am at the St. Omer Hotel. Grace.”

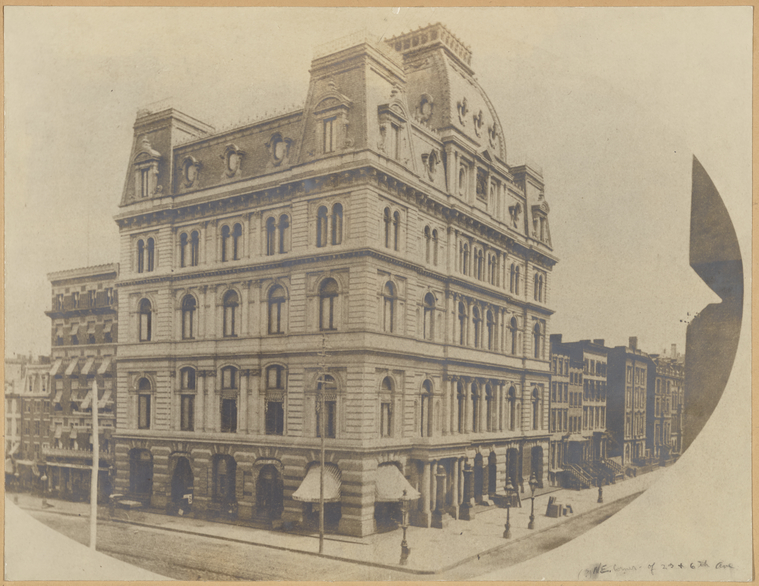

And he did. Lured by the promise of an apartment, “and nice furniture, and nice clothes,” Gracie walked out of her boarding school on West 84th Street February 27, 1889 “to keep an appointment” with Burgess. He took her to the St. Omer Hotel on Sixth Avenue and sent her in. She registered as Grace Irwin, and a few minutes later he followed, registering as E. D. Brown. “The hotel people say that they had no idea that he was in company with the girl,” reported The Evening World.

Police across the city searched for what was believed to be the kidnapped girl. Then, two days later, Gracie sent a telegram to her aunt and guardian, Caroline Smith at 312 West 84th Street that read simply, “Am at the St. Omer Hotel. Grace.”

Grace told all. The court allowed Burgess to plead guilty to assault in the second degree to avoid having the minor testify in “a crowded court-room and tell the story of her shame,” as worded by the judge. Because he was a married man, Burgess was given “such clemency as the law seems to warrant.” That translated to five years of hard labor in the State prison.

The store at 472 Columbus Avenue was home to Ambrose Schiller’s Empire Café at the time. It was a polite title for his beer saloon. He was the target of the well-known West Side Protective League in the winter of 1893. The self-righteous group sent spies into poolrooms and saloons on Sundays. On December 13, The World reported that it “had a dozen saloon-keepers on the west side indicted” for serving alcohol on the sabbath. Among them was Ambrose Schiller.

At the turn of the century, the corner store held a restaurant operated by Joseph P. Kennelly. It was a favorite haunt of Police Commissioner Sexton, a fact that seems to have buttressed Kennelly’s feelings of immunity against arrest. And so, on the night of February 1, 1901, when he saw Police Officer Hubbard ordering “a well-appointed turnout” (a type of carriage) in front of his restaurant to move along, the Irishman was infuriated.

Calling the officer foul names, he created a disturbance that attracted a crowd. He agreed to go to the station house where the sergeant charged him with disorderly conduct. As it turned out, his friendship with the commissioner paid off. Hubbard was pressured into withdrawing his charges and Kennelly was released.

Interestingly, two of the ground floor businesses changed hands in 1902. The Empire Café was taken over by George Schmitt. Unfortunately for him, he filed for bankruptcy within the year. Harschanun & Bleier next rented the space, ironically selling milk.

The store at 474 Columbus Avenue had been home to the J. G. Scharf stationery and bookstore. Scharf sold the business to Charles G. Durfee in 1902, who added cigars to the inventory. But like George Schmitt, he was unlucky in business. On April 16, 1903, The New York Press reported he had “transferred his business on March 23 to defraud his creditors.” Interestingly, he transferred it back to J. G. Scharf.

Living in the corner building at the time was the widowed Juliet P. Mara and her 14-year-old daughter, Florence. On September 7, 1904, Juliet allowed Florence to go to Coney Island with a boy who lived in the building, 16-year-old Alfred Gerard, and another teenaged girl, Florence Gerard. The two Florences went on the Loop-the-Loop roller coaster (so-called because it made a 360-degree vertical loop) while Alfred watched. Their fun ended abruptly.

The New York Herald reported that Florence Mara was “jolted from her seat and fell upon the edge of the car. Her screams created excitement, and an ambulance took her to the Emergency Hospital.” She had a compound fracture of the kneecap. Doctors performed two operations but declared “that the child will be lamed permanently.” The article added, “Mrs. Mara is angered that the management of the ‘loop the loop’ permitted her daughter, who was unaccompanied by any adult, to enter the car.”

Gordon Hendra’s family lived in 474 Columbus Avenue in 1908. That year the 15-year-old was arrested “for playing baseball in the street at Eighty-fourth street and Columbus avenue,” according to The Sun. W. E. Church appeared in court to “put in a good word” for the boy, and explained to the judge that John D. Rockefeller, Jr.’s Bible class had a department “to look after boys who are caught in minor offences.” The article said, “In spite of Mr. Church’s intercession Magistrate Barlow found the young prisoner guilty.”

The New York Herald reported that Florence Mara was “jolted from her seat and fell upon the edge of the car. Her screams created excitement, and an ambulance took her to the Emergency Hospital.”

The store in 474 Columbus Avenue was home to the Madison Laundry at the time. In 1912 it was replaced by the Economy Electrical Contractor’s Company. A clerk, Alice Brynes, went to a shoe store during her lunch hour that year and was waited on by 19-year-old Victor Klein. She chose a pair of shoes, gave Klein a $20 bill, and he promptly “went to the rear of the store and disappeared with the money and the shoes,” according to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Klein was soon caught. In court, Justice Steinert called him “the meanest kind of thief,” and sentenced him to 60 days in the City Prison.

By 1923, the store at 474 Columbus Avenue was a luncheonette. Early on the morning of March 31, three armed men walked in. The proprietor, Joseph Nod, was knocked down by the blow of a blackjack. Then he, his partner Joseph Pecortino, and their three employees were bound and gagged. The robbers took $300 in jewelry and cash from them and fled.

The corner store was Shafton’s Drug Store at the time. On March 4, 1924, fire broke out during the early morning hours. It was noticed by a passerby, Joseph Gross, who ran into the building to wake the residents. The fire spread rapidly. When firefighters arrived, they found Gross overcome by smoke and unconscious inside the building. Residents trapped on the fire escapes were rescued by fire fighters. The New York Evening Post reported that two fire fighters “were slightly injured when thrown to the curb by a powerful back-draft which caught them as they attempted to enter the building.” Twelve families were driven out.

The third quarter of the 20th century saw a marked change along Columbus Avenue. In 1973 Joe’s Sea Food Restaurant was in 474, and by 1986 Stella Flame, a men’s accessory store was in 476 Columbus. The corner store was Screaming Mimi’s by 1981. Writing in The New York Times on May 6 that year, Angela Taylor said, “Anything between the 1940’s and 60’s is camp to today’s generation and a lot of young West Siders check out Screaming Mimi’s regularly.”

Although their storefronts have been brutalized and the brick façades along Columbus Avenue are painted, the venerable buildings retain much of their handsome 1885 appearance.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

472-476 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 472-476 Columbus Avenue: