The West End Protective League Rides Again

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

When Eli Martin filed plans in October 1884 for a group of buildings at the southwest corner of Ninth Avenue (later renamed Columbus Avenue) and 81st Street, his was a one-man show. He was not only the architect, but the owner, developer, and builder. His four sets of plans called for two apartment and store buildings on Columbus Avenue, a four-story house-and-store on West 81st Street, and an abutting pair of houses on West 81st Street.

The two Columbus Avenue buildings were architecturally different from the neo-Grec style 81st Street structures. Designed in the Italianate style, they appeared to be a single structure above the storefronts. In fact, the corner building, 434-436 Columbus Avenue, was twice the size of 432 (or two-thirds of the total plot).

The large corner space at 434-436 was the perfect size for the saloon of a German-born proprietor named Gerling. But trouble came in 1891 when the West End Protective League was formed “for the purpose of restricting, as much as possible, the liquor traffic” on the Upper West Side. The group dispatched spies to watch for violations—like serving beer on Sundays—and then appealed to the Excise Board to prevent the renewal of the liquor licenses. The Evening Post noted, “All this is very harassing to the saloon-keeper,” adding, “the League prevented a saloon-keeper named Gerling from getting a license for No. 436 Columbus Avenue by making public protests.”

He continued to run the saloon at 436 Columbus Avenue and the West End Protective League continued to send in spies. Finally, late in 1892, the League had its evidence.

That did not stop Irishman John McCormack, described by The Evening Post as “the east-side saloon-keeper and ex-convict” to get a new license for the spot. The newspaper, no happier about the situation than was league, called him “a saloon-invader” into the neighborhood. The two forces were certain they had defeated McCormack and his saloon. On January 9, 1892, The Evening Post wrote, “McCormack afterwards got a license for the place, but the granting of the license was reconsidered on account of the printing of McCormack’s biography in the Evening Post and the renewed efforts of the League.”

McCormack, is seems, was more powerful than his enemies thought. He continued to run the saloon at 436 Columbus Avenue and the West End Protective League continued to send in spies. Finally, late in 1892, the League had its evidence.

On December 17, The New York Times reported it had asked the Board of Excise to revoke McCormack’s license “for breaking the law in keeping open on Sunday.” But McCormack’s attorney insisted that a license could be revoked only after the second offense. Frustrated, the League’s attorney asked for a 10-day delay to produce more evidence. “They say they have had a detective watching the saloon for over a month and have secured a large amount of testimony,” said the article. Before too long the indefatigable West End Protective League triumphed and McCormack’s saloon was gone.

In the meantime, the smaller commercial space was the real estate office of E. U. Edel. He came to New York in the 1860’s and, according Building and Architecture in New York in 1898, “was in the dry-goods business, but recognizing that his knowledge of the city and its realty values would be of great benefit to him as a broker, he decided to enter the realty market.” He focused on the Upper West Side until 1897 when he moved out of 432 Columbus Avenue “to a more central location.” The corner store then became the shop of C. J. Ulrich, “glass and china decorator.” Ulrich also did “repairing of bric-a-brac.”

Life in the apartments above the storefronts was not without drama. At 2:00 in the morning on New Year’s Day 1897 Detective Bernard F. Hughes was walking down Columbus Avenue when he heard the cry of “Murder!” coming from a third-floor window. The New York Herald reported, “The detective broke the glass in the front door and hurried upstairs.” There he found 28-year-old George F. Sternceckert and 20-year-old Sadie Bennett in the apartment of Sadie’s sister.

Sadie was crying and accused Sterncreckert of smacking her face and pointing a revolver at her. He explained to Hughes that she had taken a dollar belonging to him. Detective Hughes found a loaded revolver under a wash basin. Sterncreckert admitted it was his. “He said he and Sadie were ‘keeping company’ and that it was only a little spat,” said the article. Sadie, however, had taken enough abuse. “The young woman declared that he had struck her before, and that she intended making an example of him this time.” Sterncreckert spent New Year’s Day in jail.

“The young woman declared that he had struck her before, and that she intended making an example of him this time.” Sterncreckert spent New Year’s Day in jail.

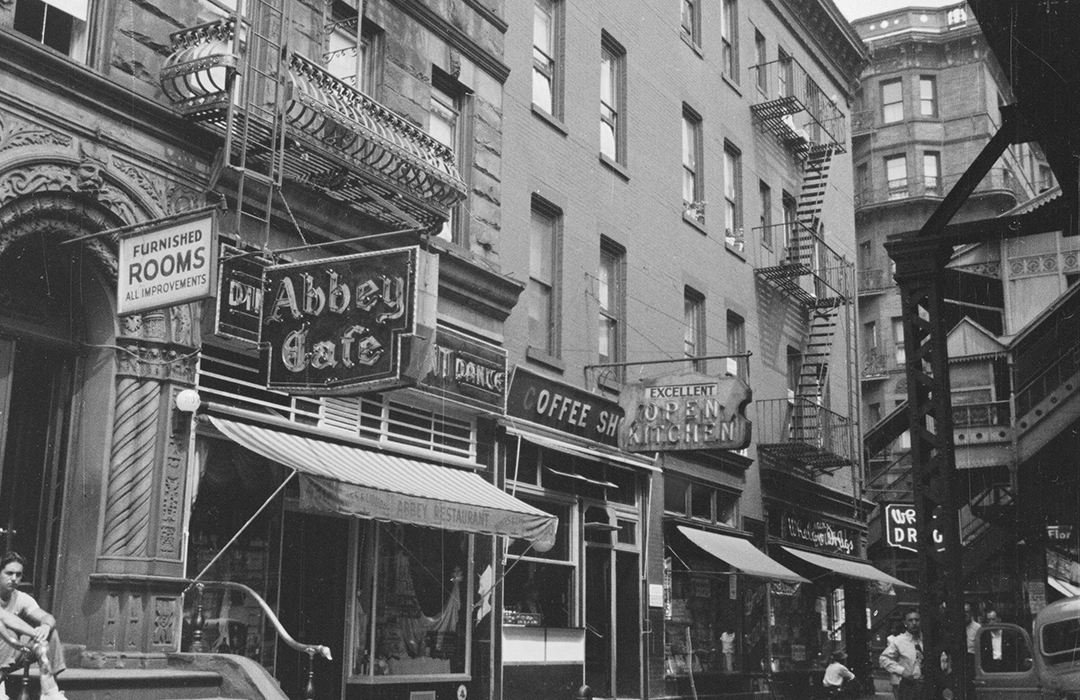

For a few years around the turn of the century, the former McCormack saloon space was an American District Telegraph Company (ADT) branch office. It then was reconverted to a saloon. It changed hands in 1913 and in its May 12 issue the New York Hotel Record reported “This place has recently been taken over by Mr. John Bittner, president of the famous Eastern Hotel.” Bittner’s brother, Andrew, was made its manager. The journal noted, “under the closer personal supervision of Mr. A. Bittner this café will become very popular, as he is thoroughly qualified and a man of pleasing and affable manners, patrons of this café can expect to get just what they call for. Mr. A. Bittner will permit of nothing but the highest class goods.”

The New York Hotel Record preferred the term “café” in describing the business, but when Bittner sold the former proprietor’s furnishings, the notice in the New York Press on April 19 announced the “auction sale of the saloon at 436 Columbus Avenue and the fixtures, etc.” In 1931 the Whelan Drug Company signed a 21-year lease on the corner space for one of its pharmacies.

Major change came to the buildings in 1978 when architects Fred C. Lary and Marvin H. Meltzer were hired to combine all five of Eli Martin’s original structures into a single apartment building. A virtual reconstruction, it was completed in 1982. The architects’ modern design incorporated a gray concrete facing, its otherwise featureless composition relieved by undulating balconies.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

432 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 432-436 Columbus Avenue: