One Fiery Bachelor Hotel at the Planetarium Arms

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

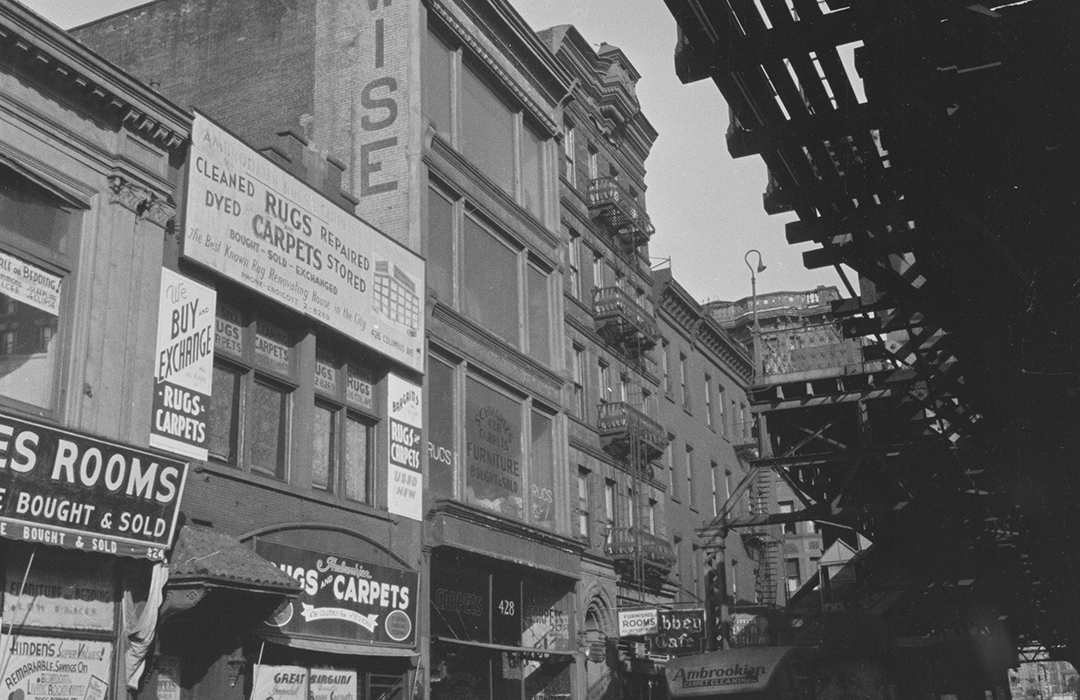

In 1890 real estate developer William Eisenberg, of Eisenberg & Wolfe, hired architect John C. Rume to design a “flat and store” building at 430 Columbus Avenue, between 80th and 81st Streets. Completed the following year, the 25-foot-wide structure rose five stories to an ambitious pressed metal cornice. Four floors of rough-cut brownstone sat upon a stone and cast-iron base. Rume drew from a medley of historic styles in designing the building. The residential entrance sat within a Gothic arch of clustered columns, keystones were carved with Viking-like portraits, and iron fire escapes were disguised as lacy basket-like balconies.

An advertisement in The Sun on November 5, 1891 touted the apartments as “6 and 7 rooms, decorated, carpeted, mirrored, and steamheated.” Rent was affordable, at least by today’s standards. The $25 per month rate in 1891 would equal about $725 today.

The commercial space became home to Joseph Lindheim’s saloon, much to the disapproval of the notoriously temperance-leaning newspaper The Evening World. It reported on November 27, “Every effort on the part of the wealthy residents of that locality was put forth to defeat this [liquor] license, but it was granted in spite of all the objections which were urged against it.”

The property was lost in foreclosure in 1895 and was purchased not long afterward by Marie S. True, the wife of prominent Upper West Side architect Clarence Fagan True. Several of the families living in the building at the time were from Ireland and the teenaged daughter of one of them prevented a disaster in 1899.

On December 1, The World reported, “Only fourteen years old, the daughter of Mrs. Agnes Sherrick, Nellie, proved herself a brave, quick-witted little woman.” Just after 6 a.m., Nellie realized the building was on fire. “Barefooted, in her night-dress, she ran from floor to floor through the fast-gathering smoke, beating on the panels with her fists, shrilly shouting the alarm.” The newspaper said she screamed, “Wake up! Wake up! Fire! Run! The house is on fire!” as she sped from apartment to apartment and floor to floor.

Nellie was amply rewarded for her heroism—more or less. “When it was all over the firemen patted Nellie’s head and told her what a fine girl she was, and the women kissed her, saying any mother should be proud of her.”

Some of the tenants were still in bed but were roused by the commotion. “Thanks to Nellie’s timely warning, all escaped unharmed,” said the article. “James McCabe and his family, who live on the top floor, ran to the roof and descended the fire-escape.” Nellie was amply rewarded for her heroism—more or less. “When it was all over the firemen patted Nellie’s head and told her what a fine girl she was, and the women kissed her, saying any mother should be proud of her.”

In June 1902 Marie True sold the property to John B. Thorpe who announced plans to alter it “into a hotel, with a restaurant on the ground floor,” as reported by the Record & Guide. Thorpe moved his own upscale restaurant into the former saloon space. The upper floors were now described as a “bachelor hotel,” although technically the 12 suites were leased to both men and women. A residential hotel, it differed from the previous flat building in that amenities like maid service were provided to the tenants. The residents were upper middle class, and no transient guests were accepted.

The building caught fire again sometime after midnight on May 24, 1903. The Sun reported, “About twenty persons were in Thorpe’s restaurant, at 430 Columbus avenue…when smoke began to pour out behind the mirrors on the side walls. The place was soon in flames, and the eaters lost no time in scurrying to the street.” A policeman tried to get up the stairs to alert the residents, “but the smoke was so thick in the hallway that he had to give up the attempt.”

Officer Cahill then rang all the doorbells at street level, eventually waking everyone. “The occupants of the apartments escaped in their night clothes by way of the rear fire-escapes and life-lines,” said The Sun. “All got out safely except George W. Armstrong, an art dealer, living on the third floor. He fell through an opening of the fire-escape and landed in the courtyard.” Armstrong suffered a broken leg and several scalp wounds. The fire, which did the equivalent of $90,000 in damages today, was quickly extinguished.

On May 25, 1904, a French manicurist, Estelle Mesguiche, took an apartment here. She had been boarding on West End Avenue, but her landlady had closed the house and gone to the country for the summer. The Sun remarked that Estelle’s “customers were wealthy women and her income was good.”

Just two days later, on the morning of May 27, Estelle “was taken suddenly ill,” as reported by The Sun. She had a maid telephone Dr. H. A. Laurent. “Before he arrived she died,” said the article.

The abrupt death of the young woman sparked rumors and mystery. The Evening World wrote, “it was reported that groans had been heard from the bathroom when Miss Mestguishe [sic] was stricken, and that shortly thereafter a mysterious man left the apartment.” After a week’s investigation, the police squelched the rumors, announcing that Dr. Laurent said she died of a heart attack and “that the ‘mysterious man’ was a life-long friend of the dead woman.”

John Thorpe sold the building in 1910. The new owner, Courtland H. Young, remodeled the storefront three years later. Architect Joseph P. Whiskeman gave it a new doorway “and grating.” He advertised the remodeled space as “excellent for lunch room.” It continued to house a restaurant for years.

Young signed a 21-year lease with the Wilder Development Company, Inc. in May 1922. The firm announced it “will make extensive alterations to the property.” The changes did not affect use of the commercial space, which continued to house a restaurant—one whose owner sought to sidestep Prohibition restrictions.

The following month, on June 11, The New York Times reported, “An automobile carrying two gallons of gin was seized yesterday by Agents Owens, Voss and Healy. The car was standing in front of the premises at 430 Columbus Avenue.” Both the gin and the automobile were seized. “Democrat Bulgerogion, 430 Columbus Avenue, said to be the owner of the car, was served with a summons.”

Furnished with “red velvet chairs, marble tables, crystal chandelier and bars on each floor,” it sold champagne for $6 per glass. “Cocaine and other drugs were also available, as well as what were described as ‘some pretty heavy gambling games,” said the article.

At least two residents in the coming decades focused on political and social issues. From 1936 through 1940, Leslie Johnson appeared on the Government’s list of Communist Party voters. And, on June 12, 1970 26-year-old William J. Dorfer, Jr. stormed into the draft board office on Varick Street with two cohorts. They began “reading the names of the war dead from a list they had carried with them,” said The New York Times. The three were arrested “as demonstrators protesting the war in Vietnam.”

A renovation completed the following year resulted in three apartments per floor, plus a duplex in the back of the store part of the second floor. The New York Times said it was now called “the Planetarium Arms, because it is across from the Hayden Planetarium, begun two months ago.” It was most likely at this time that the storefront was given a featureless, flat facing, and the exuberant cornice was removed.

The duplex apartment doubled as a business by 1973. That year, on May 24, The New York Times reported, “The police arrested 42 men and 20 women yesterday morning in a lushly appointed duplex allegedly used as an after-hours club by imps and their prostitutes.” The article said 24 policemen from the 20th Precinct and the Public Morals Division broke into the apartment “and found it packed with expensively dressed people, drinking and listening to soul music.”

Furnished with “red velvet chairs, marble tables, crystal chandelier and bars on each floor,” it sold champagne for $6 per glass. “Cocaine and other drugs were also available, as well as what were described as ‘some pretty heavy gambling games,” said the article.

After two earlier UWS homes, in 1988 Bicycle Renaissance opened in the ground floor space. Closed due to pandemic shortages, The New York Times described it in 2003 as “selling everything from the newest mountain and racing models to custom bikes built by in-house professionals.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

430 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 430 Columbus Avenue: