Fire! Twice!

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

Architect Henry Andersen was born in Flensborg, Denmark in 1852. He graduated from a private college in Copenhagen at the age of 16, then attended the Technical and Polytechnical Institute in that city. He completed his studies in architecture at the Royal Academy of Art before emigrating to New York City.

After working as chief assistant in the architectural firm of Thom & Wilson, he struck out on his own in 1892. Among his first commissions was the design for an apartment and store building, to be called The Aylsmere, for developer Leopold Kahn. Construction was not completed until 1894 but the results were worth the wait. Andersen had produced a seven-story Renaissance Revival structure faced in yellow Roman brick and lavishly trimmed in ruddy terra cotta and brownstone.

The entrance was placed on West 76th Street, away from the Columbus Avenue shopfronts. Here, banded columns uphold an entablature that announces the building’s name in bronze letters. Directly above it, Henderson placed a regal faux balcony with free-standing Ionic columns. On the fourth floor, Juliette-ready terra cotta balconettes wear Renaissance-inspired arched pediments.

The Aylsmere’s twenty-four apartments, which had either seven or eight rooms, filled with professional tenants. Among the earliest was Colonel J. Kemp Miner who arrived in January 1894. A member of the 10th Cavalry, he was Superintendent of Recruiting Services.

Dr. John Van Doren Young was another early resident. He came from a long line of physicians, being the fourth generation from William Young, a prominent doctor in Ireland. By the time he moved into The Aylsmere, Dr. Young had earned a solid reputation as a gynecological specialist.

“They rushed out in alarm, and for a time great confusion prevailed, the smoke-filled hallways being filled with frightened persons. The policeman carried one feeble woman down.”

On the ground level, The Aylsmere’s Columbus Avenue stores held a variety of businesses. Hayward & Reynolds, a newly formed plumbing firm, opened its offices early in 1894. Shortly thereafter Kruse & Hodes, “hair-dressing and manicure parlors,” took space. The salon offered “hair-dressing, shampooing, cutting, coloring, bleaching, and scalp treatment.”

The corner store was occupied by Charles Otten’s grocery store. Early in the morning of April 30, 1897 fire broke out in the rear of the store. Smoke poured out the rear windows into the air shaft and then into the hallway and open apartment windows. The night watchman was asleep on the job, but luckily an alert patrolman smelled the smoke and rushed into the building. After triggering several alarm boxes, the officer ran from apartment to apartment to rouse the sleeping tenants. The Evening Post reported, “They rushed out in alarm, and for a time great confusion prevailed, the smoke-filled hallways being filled with frightened persons. The policeman carried one feeble woman down.” The fire was extinguished with no one being harmed; although the building suffered about $220,000 in damages in today’s dollars.

Residents who could afford apartments in The Aylsmere expected high-end amenities. Following the fire damage repairs, an advertisement listed some of them: “Electric light, steam heat, elevators running day and night; bicycle room, trunk rooms; uniformed boys in constant attendance.”

The southernmost store, next to Kruse & Hodes hair salon, held Charles Havnor’s men’s barbershop. At 1:50 on the afternoon of Sunday July 31, 1898 Roger Donohue walked in and asked for a shave. Unfortunately for the barber, his customer was an undercover cop. The New York Herald reported, “Havnor shaved the policeman himself and was immediately arrested.” It was illegal for a barbershop to remain open on Sundays after 1:00 p.m.

Although Kruse & Hodes relocated in 1900, the shop continued as a hair salon, now run by Madame Steichern. In 1907 Charles Otten’s grocery store became the Catering Shop.

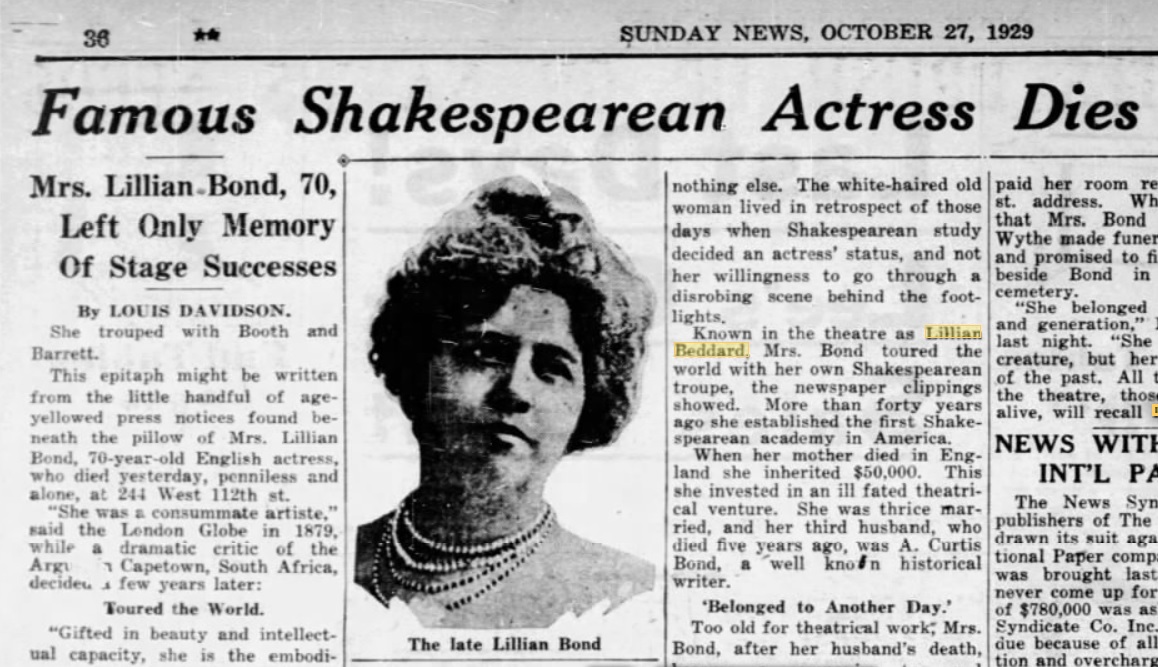

Actress Lillian Beddard was a building resident by 1910, where the Englishwoman ran a “Shakespearian Academy” from her apartment. Her ad in the New-York Tribune in March that year read “English actress will coach pupils for professional stage.”

On the afternoon of Saturday April 1, 1916 fire again struck The Aylsmere. It started in the millinery shop of Selma Waraw, quickly spread to Madame Steichern’s hairdressing salon, and then to the other store, S. Robinson’s tailor shop. As in 1897, the building’s many families crowded onto West 76th Street. Once again no one was injured, but the three stores were heavily damaged.

At 1:50 on the afternoon of Sunday July 31, 1898 Roger Donohue walked in and asked for a shave. Unfortunately for the barber, his customer was an undercover cop. The New York Herald reported, “Havnor shaved the policeman himself and was immediately arrested.” It was illegal for a barbershop to remain open on Sundays after 1:00 pm.

Post-renovations, the storefront at 333 Columbus Avenue became home to Mr. Dooley’s Bird Shop. Despite the name, it was an all-around pet shop. An advertisement on April 7, 1917 offered “German and English guaranteed singing canaries, fish, rare birds, finger-tame talking parrots, birds, cats, dogs.” A talking parrot cost $15 (about $275 in today’s money), and “skillful lady bird doctors” were on hand for ailing pets. The pet shop would remain in the space into the 1920’s.

The corner store became Irish-born George H. Kelly’s undertaking establishment after the fire. The shop suffered unwanted publicity when two of Kelly’s assistants, Frank Connell and John Kearney, tried to protect another Irishman, Bartholomew Sullivan. In December 1919 Sullivan, a cab driver, hit and killed Anna Calliess. Kearney forged the name of her daughter, opera singer Charlotte Calliess, on a document permitting burial. The dead woman was buried without her daughter’s knowledge. Both men were arrested and charged; however, the full circumstances surrounding the mysterious subterfuge were never uncovered.

That incident was followed by another messy happening in April 1921. Two women, including 22-year old Mrs. William Baker, the wife of a naval petty officer, and two men were “guests of the undertaker’s assistant,” according to The New York Herald. Despite Prohibition, the article added, “it is stated, a plentiful supply of liquor was provided.” The drinking led to “a carousal in the anteroom of the shop” during which Mrs. Baker fell down the steps and broke her spine.

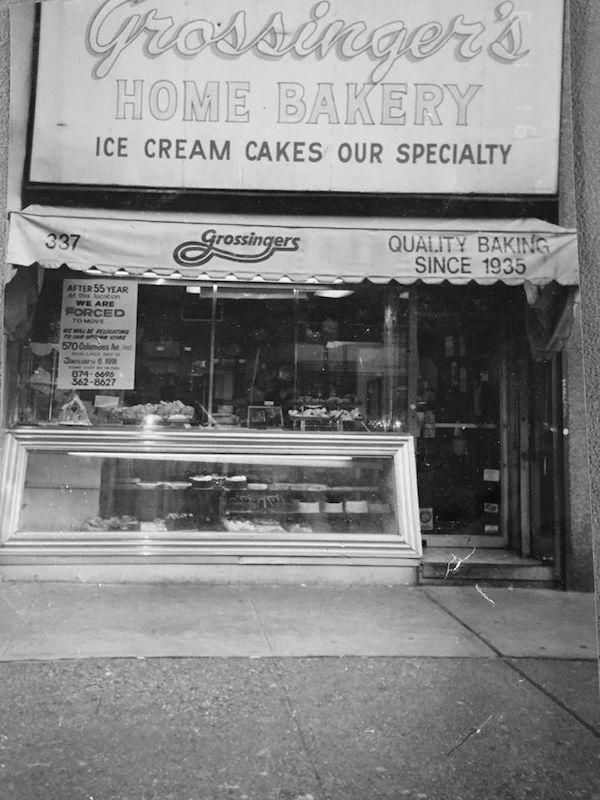

After two decades in business, Madame Steichern put her beauty parlor on the market in 1924; a hairdressing establishment would continue to do business there for years. In 1935 Hungarian baker Ernst Grossinger opened Grossinger’s Home Bakery in the corner store; he and his wife Isabella and their children lived upstairs. The shop and its personalized cakes, later run by Ernst’s son Herb, remained a part of the community for 56 years.

In the mid-1950’s Roberta “Bobbie” Eis came to live in The Aylsmere. Her sometimes roommate (he had his own apartment on Bleecker Street) was budding actor Warren Oates, whom she met in a bar. It was not the building’s only brush with entertainment. In the 1990 movie Green Card Andie MacDowell’s character, Bronte, lived in here; and a scene in the television drama “Law & Order” was filmed in the store at 339 Columbus Avenue in 2001.

Local favorite Cherry Restaurant (“The Cherry”) was opened in 1938 at 335 Columbus by a Japanese restaurateur. It remained there (under a different owner after 1960) until 1991 when it and the women’s apparel store Putumayo were forced out by The Gap. Today all of the storefronts have been combined for a bank.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

331-339 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 331-339 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Huntley Gill!