The Hartford’s Stowaways of Bedloe’s Island

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

In November 1889 architect Frederick T. Camp filed plans for a “six-story flat” to be built on the southeast corner of Ninth Avenue (soon to be renamed Columbus Avenue) and West 75th Street. A construction project would cost its developer, John P. Ryan, the equivalent of just under $1.3 million today.

The Hartford was completed the following year. Ryan had created a mélange of currently popular architectural styles—Romanesque Revival, Queen Anne and neo-Grec. The two-story base was clad in rough-cut granite, while the upper four floors were faced in more formal red brick. The architect splashed the façade with two whimsical double-wide brick eyebrows that straddle chimney bays on the Columbus Avenue side, oval hallway openings on the side elevation, and creative brickwork. The double-doored residential entrance on West 75th Street was a Camelot-ready Arthurian fantasy.

There were two storefronts on the avenue side. In the 1890’s the southern store was home to the shop of Andrew Gillies, a furniture designer and marker. Gillies was an all-around decorator and sold upholstery and “decorations” in his shop as well. His advertisements offered “Estimates and Designs furnished for special work.” The northern store was L. Katz’s art gallery. When he opened a new exhibition of paintings in November 1899 The New York Times remarked, “Mr. Katz made an excellent exhibition last year, which was much enjoyed by the art lovers on the west side.”

Apartments ranged from seven to eight rooms with a bath, and the building’s up-to-the-minute amenities included “steam heat and hot water; all-night elevator service; [and] reception room.” The reception room was an especially attractive feature for well-to-do tenants. Their guests could not only wait for them in comfort there, but lady callers intending to visit could remove their coats, hats and muffs and otherwise ready themselves before arrived at the door.

The residents of The Hartford were well-heeled. Among the initial tenants was Dr. Cyrus J. Strong who was secretary of the board of trustees of Bellevue and Allied Hospitals. He would remain in the building at least through 1909.

Catharine Tojetti was the widow of artist Virgilio Tojetti who died on March 26, 1901. Born in Rome in 1851, the son of celebrated artist Chevalier Dominico Tojetti, he had decorated the mansions of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, John D. Rockefeller and Lispenard Stewart. One of his paintings sold by the National Academy in 1883 had brought the highest price ever paid for a picture in the Academy to that date.

Catharine had two daughters, Madeline, who was married, and Zelica Grace, who was 14 at the time of her father’s death. Catherine and Zelica moved into The Hartford soon afterward. Living with them was Zelica’s governess.

Early in 1904 the governess was “dispensed with,” as worded by the New-York Tribune. A few weeks later, on April 4, Zelica (who was now 17) left home, telling her mother “she intended to visit a friend in Seventy-eighth-st.,” as reported by the New-York Tribune. She did not return. When inquiries were made at the friend’s house, it was learned that the girl had never arrived there. The following day the New-York Tribune reported “relatives and friends have been searching the hospitals and police stations. Her mother is prostrated.” The newspaper added, “The girl is declared to be extremely pretty.”

The evening was not being pleasantly passed in Catharine Tojetti’s apartment in The Hartford. The disconsolate widow could only assume her young daughter had been abducted or worse.

As it turned out, Zelica never intended to visit that friend, but a relative, Johanna Luchra who worked on Ellis Island as a stenographer. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle explained, “it was planned Miss Luchra would return to Manhattan with Miss Tojetti and spend the night with her.” They left Ellis Island on the 1:40 boat, but having just sailed past the Statue of Liberty, they decided to visit it before heading to The Hartford.

Their innocent sight-seeing turned to adventure when, after having climbed to the top of the monument, they found the exit doors locked for the night. Hours later, at 7:30, they shouted to a sentry through an open window. He unlocked the door and took them to the quarters of Captain Burnell, the commanding officer of the Island.

Burnell, who was a bachelor, was “considerably concerned” about appearances. The last boat had left Bedloe’s Island hours ago and the girls were marooned there. So, he took them to the quarters of the Port Surgeon, Dr. Newlove, whose wife took them in. “A bounteous dinner was served,” said The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “and afterward the girls were taken to Captain Burnell’s quarters, where they were serenaded by the post band and the evening was pleasantly passed.”

The evening was not being pleasantly passed in Catharine Tojetti’s apartment in The Hartford. The disconsolate widow could only assume her young daughter had been abducted or worse.

Early the next morning a sentry saw “Honest Bill” Quickly tie his rowboat at the Bedloe Island pier. “Quigley was pressed into service and he rowed the girls to Ellis Island.” No doubt anticipating her mother’s reaction, Zelica telephoned her sister and told her she was safe and would arrive home in a few hours. The following day a national wire service report announced “Pretty Miss Zelica Grace Tojetti, the young art student whose disappearance from her home in the Hartford apartments, 60 West Seventy-fifth street, cause a general police alarm to be sent out and created considerable excitement in her family circle, turned up all right after one of the most romantic adventures heard of in this country in years.”

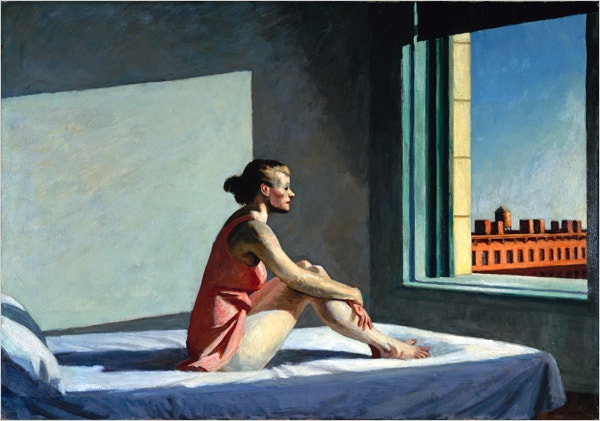

Another female artist moved in in 1909. Following her father’s death, public school teacher Josephine Nivison took an apartment with her mother and her brother. She would become known now only for her own art, but as a frequent model for her renowned artist husband, Edward Hopper, whom she married in 1924.

In 1912 rents in The Hartford ranged from $55 to $75, the equivalent of about $2,000 per month today for an eight-room apartment. At the time the southern commercial space was home to James Van Dyck Card’s real estate office, while a commercial laundry operated in the northern space.

The names of the residents appeared more often in society columns than for any sordid reasons, such as the announcement in the New York Herald on September 18, 1913 that “Mrs. John Haven Pugh…has returned from Europe. Mr. Pugh joined her abroad for part of the summer.” Among the well-respected families in the building was that of Joseph Cudlipp, who families were “old settlers of Bloomingdale, New York city,” according to the New York Herald in 1917. Cudlipp, who served in the Civil War, had grown up in the family homestead at 76th Street and the old Bloomingdale Road, later Broadway. He and his wife, the former Jane Hill, were married in 1864.

Nevertheless, an occasional resident appeared in the press for the wrong reasons. Marian L. La Touche, the widow of Royal La Touche, was 66-years old in 1917. Decades earlier, on December 8, 1887 she had been arrested on a charge of swindling. At the time The Patterson Morning Call said, “A number of ladies visited police headquarters who said they had been swindled by the prisoner of sums ranging from $300 to $1,000.” And, on September 21, 1905 The World ran the headline “Mrs. La Touche Sent To Tombs” and reported she had been arrested for swindling Julia Wetter in a series of phony stock transactions.

Now Marian was living in The Hartford and still practicing her old ways. Police knocked on her apartment door on August 3 and arrested her for grand larceny. Assistant District Attorney Weil called her the “most noted swindler of women ever arraigned in a New York court.” She was arrested on a complaint by Anna M. Fitzgerald, but Weil told reporters that Marian had “procured hundreds of thousands of dollars from other women and that she was one of the most successful ‘get rich quick’ operators Wall Street ever had.”

Although 44-year old jeweler Max Berenstein was a married man, he was infatuated with a young modiste, or dressmaker, Christina Magrauder, who lived in Greenwich Village. The young woman was a con-artist and thief and in October 1922 she stole $7,000 worth of jewelry from Berenstein. When he went to her apartment to confront her, he “found two strong men waiting to receive him,” according to court documents later. They threatened to expose his affair to his wife and ruin him professionally. He was locked in the apartment, presumably to think about what he should do, and after they left, he noticed that the furniture had been damaged and some of Christina’s furs and dresses were on the floor.

In the meantime, Christina went to the police station and complained that Berenstein had argued with her and was rampaging through her apartment. Berenstein was arrested for destroying items worth $4,000. Because he was afraid of being exposed, he paid the $2,500 bail and remained quiet.

Rather unbelievably, he continued his sexual affair with Christina Magrauder. On December 10, 1922 they spent the night together at the Hotel Commodore and, according too his attorney, “while he was asleep she went through his purse and stole a diamond and sapphire brooch and a three-stone diamond ring valued at $3,000.” The total value of the jewelry would be more than $76,000 today.

This time Berenstein wised up. He confessed everything to his wife and then had Christina arrested. Mrs. Berenstein appeared in court with her husband on the day of the trial.

On October 1, 1930 17-year old John Peters was arrested on a Tenth Avenue roof after having robbed an apartment at 307 Columbus Avenue. The Times Union said, “Peters is also alleged to have participated, Sept. 29, in the burglary of the apartment of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Weaver, at 60 West 75th st…in which $50 was taken and jewelry valued at $5,000 overlooked. A watch reported stolen from the Weaver apartments was found in Peters’ possession.”

Living with the Weavers in The Hartford was their daughter, Alice, a showgirl. She had a decided distaste for police after having recently been arrested with other cast members of My Girl “on charges of presenting an immoral show,” according to the Daily News. The arrest of John Peters gave her the opportunity to get even.

Rather unbelievably, he continued his sexual affair with Christina Magrauder. On December 10, 1922 they spent the night together at the Hotel Commodore and, according too his attorney, “while he was asleep she went through his purse and stole a diamond and sapphire brooch and a three-stone diamond ring valued at $3,000.” The total value of the jewelry would be more than $76,000 today.

On October 6, she was called to the police station to sign a complaint. The Daily News said “That grand old maxim, ‘Tit for tat is no robbery,’ was demonstrated yesterday by little Alice Weaver—who figured so noticeably in the disrobing scene of ‘My Girl’—at the expanse of the police department which once closed her show. Of course, Alice couldn’t retaliate by raiding a police station. But she did the next best thing by refusing to help detectives jail a 17-year-old burglary suspect.”

Alice said she could never file a complaint “against a mere boy.” And when detectives said, “But he had your papa’s watch in his pocket,” she repeated, “Never! And I’ll tell my father not to sign any complaint either.” Alice got her revenge and the burglar went free.

Following the end of Prohibition, 315 Columbus Avenue became a tavern, operated by Oscar Cooperman. Beginning in the 1950’s the King Cole Supermarket occupied 313 Columbus Avenue. It would remain for over two decades.

The series of shops in the two locations reflected the changes in the Columbus Avenue neighborhood. In 1979 a Haagen-Dazs store opened in 313, followed by the Green Noodle Restaurant in 1984.

A third commercial space, created on the 75th Street side in 1984, was the housewares store Random Harvest for several years before becoming Feline Salon, a spa that offered treatments like its “herbal mummy wraps” and “cocoon seaweed wraps.”

Gilberto Pinto lived in the building in 1986 when the Colombian national was convicted for having headed a cocaine-smuggling operation for about three years. His ingenious scheme used swimmers who sometimes spent up to nine hours in the waters of the East River to retrieve drugs lowered overboard from Colombian ships.

A horrific tragedy played out in the apartment that 65-year old Christina Payamps shared with her two sisters in 1991. On the evening of December 12 her sisters returned from work to find her dead. Police Sergeant Edward J. Burns said, “The body was in the dining room, with the throat slashed.” There was no sign of forced entry and no apparent motive.

A renovation completed in 1992 resulted in a total of 22 apartments in the building. Today a spa and nail salon operates from the 75th Street store, and a wine shop and window shade shop are in the Columbus Avenue locations.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

313 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 313 Columbus Avenue / 60 West 75th Street:

Meet Jeannie Gesthalter