The Ice Cream Depot

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

In 1884 New York’s Great Industries boasted “the J. M. Horton Ice Cream Company to-day stands unrivaled in its line, head and shoulders above all competitors, and with an international reputation for supplying the purest and most palatable ice cream ever manufactured.” At the time of the article, the wholesale and retail manufacturers operated four outlets in Manhattan and one in Brooklyn.

James Madison Horton was born near Middleton, New York in 1835 to a well-to-do farmer. While still a teen, Horton came to New York with $100 and went into the milk business. Just four years later, while not yet 20 years old, he was made president of the Orange County Milk Association. Horton’s ill health forced him to turn his company over to other management, which ran it into the ground. With his firm on the brink of collapse, Horton returned to the helm. “His health being restored by this time, he threw all his energy into the work,” said the New-York Tribune decades later.

Not only did Horton revive his dairy firm; in 1870 he recognized a new opportunity: ice cream. He incorporated the J. M. Horton Ice Cream Company in 1872 with three partners. Within the decade his was the most recognized name in ice cream in the country.

So great was the success of the company that in March 1889 it hired the architectural firm of Cleverdon & Putzel to design a large office and factory on 125th Street. Almost simultaneously the architects were given the commission to design a five-story store and tenement at 302 Columbus Avenue.

Completed in 1890, the Columbus Avenue structure was five stories tall. A blend of Renaissance Revival and Romanesque Revival styles, it was faced in red brick above a cast iron storefront. Highly unusual decorative bands of terra cotta tiles above the third and fourth floors depicted swirling palm fronds. Above it all, an ambitious cornice with a triangular pediment announced the J. M. Horton name.

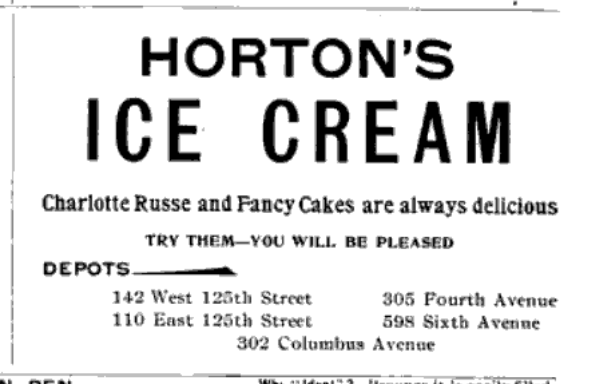

Customers to the store could choose from a variety of frozen treats: “ice cream, water ice, charlotte russe, and jelly.” While we tend to imagine such Victorian shops as “ice cream parlors” with picturesque wire furniture and mustachioed servers with arm garters, J. M. Horton Ice Cream Company had a more industrial-sounding term for its stores: ice cream depots.

Customers to the store could choose from a variety of frozen treats: “ice cream, water ice, charlotte russe, and jelly.” While we tend to imagine such Victorian shops as “ice cream parlors” with picturesque wire furniture and mustachioed servers with arm garters, J. M. Horton Ice Cream Company had a more industrial-sounding term for its stores: ice cream depots. (The term “depot” derived from the fact that, while individual customers could stop in for a treat, the main purpose for each branch was to supply orders to nearby “hotels, restaurants, steamboats, steamships, church fairs, Sunday school festivals, weddings, balls, excursions, families, etc.”)

The Columbus Avenue store received deliveries from the main plant, in Brooklyn, which cranked out 40 quarts of ice cream every 20 minutes. There, 150 employees created and packed the product, which was delivered by 60 wagons and 75 horses. New York’s Great Industries added, “The company owns two ice houses of twenty-two thousand tons capacity, at New Baltimore, N.Y., where each winter they store the pure crystal from the Hudson, at a point where the ice is acknowledged always to be of superior quality and purity.”

The firm that had offered four items in 1884 had greatly expanded its product line at the turn of the century. In 1904 the list of flavors rivaled those in any franchise store today: “Biscuit glace, tortoni, praline, tutti frutti, pudding nesselrode glace, stanley glace, diplomate plombiere and mousse cafe, marrons, mill frutti, cardinal, roman and lalia rookh punch and many other flavors are prepared for summer resorts, weddings, restaurants and hotels,” read an advertisement.

The ice cream depot was still in the Columbus Avenue building in 1904; but, while J. M. Horton Ice Cream Company retained ownership of the property, it had closed the store by 1908. Henry A. Flagg ran his grocery store there and that year he was the chief among several complainants against 28-year old Lester Hoffstadt.

Hoffstadt had presented Flagg a check for $25–a significant $665 today. It was a forgery. When Flagg had him arrested and Hoffstadt appeared before the judge, two other merchants showed up. The New-York Tribune reported, “The other complainants averred that he passed the worthless instruments upon them.”

In 1912 James Horton, now 77 years old, transferred most of his real estate to his two children. Although he had no intentions of retiring, he told reporters “I am getting to be an old man and am not in the best of health, and I wanted my property in shape.” Among the properties received by Chauncey E. Horton, a director in the firm, was No. 302 Columbus Avenue.

Two years later, in February 1914, Horton hired architect Edwin Krows to “reset store fronts” on the building. The renovations cost $200 (about $5,280 today).

When the building was sold in 1921 for $65,000 (about $860,000 today), Smultan’s Auction Rooms operated from the store space. In the meantime, blue collar families, many of them newly-arrived from Ireland, came and went in the tenement apartments upstairs.

One resident, Michael Torman, went to the bachelor apartment of a friend, Roy Huston, at No. 313 West 25th Street, to play cards on the night of October 18, 1924. Like Torman, the six other men were iron workers. Sometime past midnight three masked men barged into the apartment, all armed.

The players were lined up with their backs to one gunman while the others took the money from the card table, then emptied the men’s pockets one by one. When the robbery was nearly completed, Torman shifted his weight from one foot to the other. The seemingly innocent movement was too much for the jittery gunman.

One resident here during the Great Depression narrowly escaped being robbed. On March 3, 1936 policemen John J. Broderick and Frederick Stepat noticed a suspicious man in the ground floor hallway. They were later awarded for their keen vigilance after arresting the man “while he was in the act of stealing an envelope containing a check from the mail box.”

“As he did so the thief covering the seven men fire two shots point blank at him,” reported The New York Times. “The first bullet missed him, embedding itself in the wall, but the second struck him in the left side of the abdomen.”

As Torman fell to the floor the thugs backed out, slamming the door. The wounded man was taken to Bellevue Hospital in serious condition.

One resident here during the Great Depression narrowly escaped being robbed. On March 3, 1936 policemen John J. Broderick and Frederick Stepat noticed a suspicious man in the ground floor hallway. They were later awarded for their keen vigilance after arresting the man “while he was in the act of stealing an envelope containing a check from the mail box.”

The old tenement building received a make-over in 1978. The renovations resulted in a remodeled restaurant space at street level and three apartments on each of the upper floors. The renaissance of Columbus Avenue continued and in 1993 the Red River Grill opened.

Today a 20th century fire escape zig-zags down the facade and the much altered store–where Victorians stopped for ice cream and charlotte russe–is a sandwich shop. But high above Columbus Avenue, the cornice still loudly announces the name of James M. Horton Ice Cream.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

302 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 302 Columbus Avenue: