Barnett Bros.’ Burglaring Brothers

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

Around 1894 the Barnett Brothers Department Store erected a commercial structure on the southeast corner of Ninth (later Columbus) Avenue and 74th Street on property leased from Frederick Ambrose Clark, who was 12-years old at the time. The teen had inherited a large amount of undeveloped Upper West Side property from his millionaire grandfather Edward Clark.

Formed by brothers E. G. Barnett, I. L. Barnett and I. H. Barnett, the store rapidly grew and on October 26, 1895 the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that architect George H. Griebel had been hired to enlarge the building.

On November 23, 1898 Printers’ Ink wrote, “There is a store in New York, at the corner of Seventy-Fourth street and Columbus avenue. It is getting to be quite a store. Only a few years ago it was an unimportant concern in a single store-room. Now it occupies a building two stories high, half a block long, and fifty or sixty feet deep.”

Barnett Brothers’ rapid success was due mostly to its Upper West Side location where few such stores were yet operating. “It is a better store and a bigger store each year,” said Printers’ Ink. “The trade comes to it because it is convenient. It is a good deal easier for people in the neighborhood to go to Barnett’s than it is to get on a car and go three miles to Wanamaker’s.”

Barnett Brothers was a true department store, offering not only dry goods and apparel, but housewares, china and glass, and other items. As the neighborhood developed and the population increased, so did the store’s business. On February 15, 1902 the Record & Guide reported that the Clark Estate (Frederick, known as “Brose”, was still a minor at 19 years old) had again hired George H. Griebel–this time to replace the two-story building with a “six story brick and stone dry-goods store.” Griebel estimated the construction costs at $350,000–a significant $10.5 million today.

The result was a handsome blend of commercial neo-Renaissance and Beaux Arts styles. Griebel’s proposed six-story structure was, however, just four at completion.

At a meeting of the New York Wholesale Grocers’ Association Herman Rohrs growled, “Pretty soon these dry goods stores will be advertising coffins free in order to induce people to buy flour. They’ll be offering inducements to people to die.”

Now in its impressive new building, Barnett Brothers continued to expand its offerings. In its March 1906 edition The Millinery Trade Review noted, “Barnett Bros…have opened on the third floor of their well-appointed establishment a millinery department…The department presents a particularly handsome appearance, occupying about one-third of the floor, the remainder of which is devoted to the garment stocks.” Saying that there would most likely soon be a workroom for custom trimming hats, the article noted, “The fittings are in mission oak and the soft green rugs make an effective setting for the many-hued millinery display.”

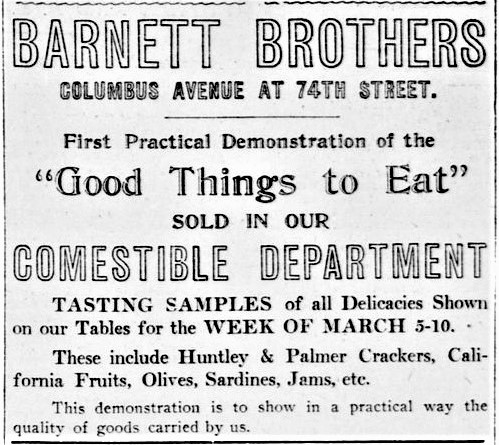

That same month the store opened its Comestible Department, a sort of precursor of the gourmet shops in today’s department stores. The selling of food in department stores was a trend that greatly upset the city’s grocers. At a meeting of the New York Wholesale Grocers’ Association Herman Rohrs growled, “Pretty soon these dry goods stores will be advertising coffins free in order to induce people to buy flour. They’ll be offering inducements to people to die.”

Just before Christmas in 1907 burglars broke into the building through an alleyway window and eluded the night watchman by hiding behind counters. They made off with a tray of gold rings. It was one of a string of similar burglaries in the neighborhood–a grocery store’s cash register was stolen, and seven revolvers taken from an automobile supply store, for instance. And then the crooks revisited Barnett Brothers. On January 3, 1908 The New York Times reported, “This time they got a trayful of watches, but the theft proved their undoing, for the detectives traced it to them.”

The arrested thieves, John Townsend, a.k.a Red; his brother, George; and William McGlynn, alias Fatty, gave full confessions (although “Red” Townsend was intoxicated at the time). It was not the brazen deeds of the trio that amazed detectives and the public, but their ages. “Red” was 10-years old, his brother was 8, and “Fatty” McGlynn was 9.

On February 26, 1921 The New York Herald reported “Barnett Bros., who have occupied the building at the southeast corner of Columbus avenue and Seventy-fourth street since its erection thirty-five years ago, have purchased the property.” Calling the building “a landmark in this section,” the article placed the selling price at $350,000, or just under $5 million today.

Surprisingly, the department store survived only a few more years. On January 27, 1925 The New York Times reported that the building “formerly occupied by Barnett Brothers Department Store…has been leased to the Flohar Realty Corporation.” The operators signed a 42-year lease and announced that the architectural firm of Sugarman & Berger to make significant changes. “The building is to be completely altered with the addition of two stories,” said The Times.

Above the street level shops was a floor of offices and showrooms on the second floor, and “studios and non-housekeeping apartments” on the upper floors. Three of the studio apartments on the fifth floor were leased by the Federation for Child Study and converted to schoolrooms. The organization was the outgrowth of the Society for the Study of Child Nature, formed in 1888 by five women with the goal of studying children from “the mental, moral and physical view points.” A pioneer organization in the research of child development, it was by now supported by grants from the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Memorial Fund.

In the meantime, the ground floor shops were leased to small businesses like “Mickey” Connor’s barbershop in No. 293. The Irish immigrant held his opening night party on November 8, 1925. The Irish-American newspaper The Advocate reported “There were song and dance in plenty and other things.”

Another renovation, completed in 1943, resulted in apartments on the upper floors, along with a dental lab on the third and a gymnasium on the fourth. The corner shop continued to house a restaurant and in the spring of 1950 it was leased to Irish immigrant Patrick Jordan and his wife, who ran the Paddy Jordan Restaurant.

The corner shop was leased to the Seventy-fourth Street Restaurant, Inc. The firm sold its lease in October 1930 to the Lincoln Cafeteria, Inc. The space would see a succession of restaurants during the Depression years. Bill’s Chop house opened in 1932, and Andrew Jainke’s restaurant was here in 1935 when the owner was held up at gunpoint at 2:00 on the morning on January 20.

The gunman, 22-year-old James Toomey, made off with $14 from the cash register, but not without a fight. As Toomey rifled through the register, Jainke started to lower his raised arms. The crook fired a single shot and Jainke pounced. Hearing the gunshot, three policemen rushed into the restaurant. The New York Post reported “Toomey fought desperately when the three patrolmen arrested him for violating the Sullivan law by possessing a .32-caliber revolver and for robbery.” Toomey never made it to jail. He was taken to Flower Hospital with broken ribs and scalp lacerations. His admittance card listed the place and circumstances of his injuries as “unknown.” He died on the operating table there.

Another renovation, completed in 1943, resulted in apartments on the upper floors, along with a dental lab on the third and a gymnasium on the fourth. The corner shop continued to house a restaurant and in the spring of 1950 it was leased to Irish immigrant Patrick Jordan and his wife, who ran the Paddy Jordan Restaurant.

Nine years later the shops were consolidated into a single store, taken by Pioneer Supermarket. What remained of Barnett Brothers’ limestone storefronts were covered over by an unflattering facade. The upper floors, however, still hint at the department store and a time when Upper West Side ladies shopped for the latest in hats and fancy “comestibles.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

289-295 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 289-295 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Lenny Franzblau!