The Split-Personality Greystone

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

Among the few professions in which women could prevail in 19th century New York was real estate. One of those was Margaret Brennan who bought and sold properties throughout the city for decades beginning in the early 1870’s. In 1886 she hired the well-known architectural firm of Thom & Wilson to design a five-story flat building with stores at the southwest corner of Ninth Avenue (later Columbus Avenue) and West 74th Street.

Construction was completed the following year. The architects have given the building an architectural split personality. The Columbus Avenue side, lined with stores at ground level, was faced in red brick and trimmed in stone. Its neo-Grec design included recessed panels in the chimney backs and a prominent parapet above the cornice. The residential side was Renaissance Revival in style, faced in rough-cut stone and touting carved lintels and decorative panels, and an impressive entrance above a short stoop with beveled glass double-doors beneath an arched overlight with the building’s name painted in gold lettering: The Graystone.

The stores filled with a variety of tenants. One was another female professional, M. M. Gill who opened a second office of her New York branch of the London and Lancashire Fire Insurance Co. here. On May 20, 1898, The Record & Guide wrote “From time to time we have noted the successes scored by women who have become workers in the real estate world, and now we take pleasure in calling attention to the successful work done by a woman who makes a special of fire insurance. Eight years ago Miss M. M. Gill established the business…A year ago Miss Gill opened a second office at No. 294 Columbus avenue, corner of 74th street, which owing to its central location and business-like management, promises to be as successful as the 3d avenue office.”

Another commercial tenant was Carter & Robertson, a pharmacy in 288. It had apparent good success with a particular patent medicine. One of the proprietors said in a testimonial in The Evening World in 1894, “The sale of Paine’s celery compound is improving wonderfully. I have heard customers say that they found it an excellent remedy, women particularly, who are sufferers from nervous difficulties.”

Philip Schwartz operated his shoe store in another space at the time. He personally made the shoes that were sold in his shop.

The residents of The Graystone were financially comfortable. Among the first to move in were the widowed Mrs. MacArthur, her four-year-old son, and her mother, Olive M. Winston. The women had one servant. Rent on their apartment of six rooms and a bath in 1897 was $40–or about $1,270 per month today.

On January 29, 1902 he sent Dolly a bill on his office stationery which bore the heading “Zane Grey, D.D.S. 100 West Seventy-Fourth Street, New York City,” he charged her $86 million dollars…

The population of the MacArthur apartment was increased by one in January 1898. Olive Winston’s son, Walter, was required to be away from his wife for months at a time. She found a “paramour,” as described by the courts, and bore him a child. (A physician determined paternity based on the time of conception, when Walter was absent.) During the divorce proceedings, Olive came forward and petitioned for custody of the little girl, despite the fact that she was almost assuredly not related to her. That a respectable Victorian grandmother would seek to care for a bastard child was startling. The judge ruled in her favor.

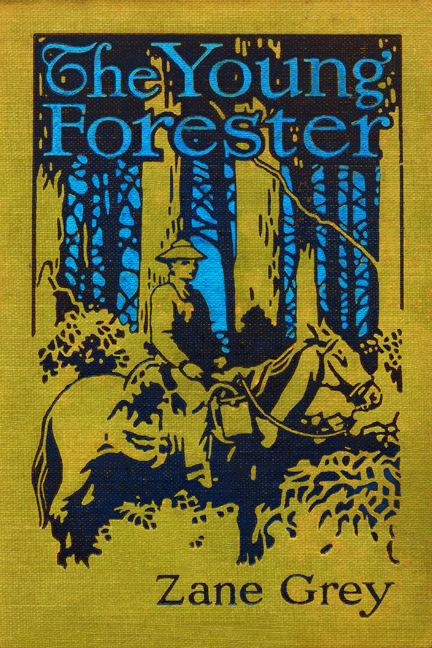

In 1899, a 27-year-old dentist from Ohio moved in and established his office here. A bachelor, Zane Grey had graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Dentistry in 1896 and filled his spare time in the summer months playing semi-professional baseball for the Orange Athletic Club. At the kitchen table in his apartment in The Graystone he tested his skills at his true passion–writing.

Zane Grey slipped easily into New York and Brooklyn social circles. When Jane Kenyon Salisbury and Harold Winchester Chapman were married on December 18, 1900 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called it “among the weddings of the year” and “most notable.” The eight ushers came from as far away as Boston and Chicago and included “Dr. Zane Grey of the borough of Manhattan.”

Earlier that year Grey had been canoeing on the Delaware River where he often fished with his brother, R. C. During that trip, he met 17-year-old Lina Roth, known to her friends as Dolly. The dentist-writer fell head over heels.

On January 29, 1902 he sent Dolly a bill on his office stationery which bore the heading “Zane Grey, D.D.S. 100 West Seventy-Fourth Street, New York City.” He charged her $86 million dollars for:

18 months torture, unrest, dissatisfaction, trouble, hard work

for loss of many nights sleep

for loss of peace of mind

for loss of heart

for loss of ability to admire any other girl

for inclination to depreciate myself

for a constancy I never dreamed I possessed

for the sweet, blind, tumultuous feeling that allows no rest

He ended his invoice saying, “In consideration of the fact that I must be paid at once, if you have not the money I will accept your soul–no less.”

A few months later, in May, Grey was interviewed by a reporter from The New York Times regarding the proposal to raise the speed limit on motorcars from 8 to 10 miles per hour. He was adamant in his opposition. “I was nearly killed by an auto yesterday, and hereafter I shall carry a gun. Nothing but a bullet could have caught this one.”

That month was an important one for the young dentist. Grey’s writing had been routinely rejected by New York publishers. Finally, his first article “A Day on the Delaware” appeared in the May issue of Recreation Magazine. The following year he finished his first novel, Betty Zane. He would go on to become one of America’s most popular novelists for his stories of the Far West. In 1904, Grey left his apartment where his literary career began and the following year he and Dolly were married.

Other tenants in The Graystone included policeman John G. Hayes and his wife, Caroline. He retired in 1898 and began collecting his pension of $480–about $15,300 per year in today’s money. Following his death in 1901, the city cut the pension by more than half, giving Caroline an annual income of $143.22. She remained in the apartment at least through 1905.

At the time Solomon Weisbaden (who went by Sally) ran his business from the store at 294 Columbus Avenue. It was a bizarre combination of jewelry store and optometry office. On June 1, 1905, Dr. William F. Arnold brought in a pair of gold-rimmed bifocals to be repaired. Arnold was a retired naval surgeon and he had lost the sight in one eye in the Philippine-American War. The New York Times explained “To preserve the sight of his remaining eye, Dr. Arnold declares, he was compelled to wear spectacles with lenses ground according to a complicated formula.”

Sally Weisbaden found himself in court just two weeks later. Arnold sued him for the equivalent of $90,000 today, charging that he “ignored the instructions and prescription and improperly adjusted the lenses, so that the sight of Dr. Arnold’s remaining eye was impaired, making it impossible for him to attend to his ordinary occupations.”

In 1915, the shop that had been home to Weisbaden’s jewelry and “oculist” business became the embroidery store of Eugene Coussa. Other stores were occupied by Charles Ericson’s plumbing shop, and Naiman & Siegel’s novelty store.

In 1917, Eddie Root, described by The Sun as “a widely known bicycle racer,” was in France serving in the aviation section of the U. S. Army. His wife, Florence, remained in their Graystone apartment. At around 11:00 on the night of September 8 she was at the corner of St. Nicholas Avenue and 125th Street when an automobile occupied by four men pulled over and offered to take her home.

Arnold sued him for the equivalent of $90,000 today, charging that he “ignored the instructions and prescription and improperly adjusted the lenses, so that the sight of Dr. Arnold’s remaining eye was impaired, making it impossible for him to attend to his ordinary occupations.”

Unthinkable today, she accepted. She was driven into Van Cortlandt Park “despite her protests,” according to The Sun. They stopped the car in a dark area where the four men attacked her. The article said, “She fought them off, but they seized a diamond pin valued at $500 and $28 in bills which was in her stocking. The men left her in a dazed condition on the sidewalk in front of Shanley’s restaurant in Yonkers.” Based on Florence’s descriptions, four men were arrested two days later.

In December 1919, resident Mrs. J. Gould found a dog roaming the street and took it in. It turned out to be Lady, the “Belgian police dog valued at $3,500” owned by silent film actress Jeanette Horton. After several days, the actress answered Mrs. Gould’s ad and offered her $5 as a reward. It was not enough, according to Mrs. Gould, who took her to court. She complained that “during the several days she had it, it destroyed $200 worth of property.”

Charles Ericson’s plumbing shop remained in the Columbus Avenue space into the 1920’s. Other commercial tenants included Kelly Brothers Moving company, here in the 1940’s. During the last quarter of the 20th century trendier shops appeared, including the antiques store Coccabahi at 292 in the 1970’s. New York Magazine described owner Jeffrey Weiss’s offerings as his “motley, mostly turn-of-the-century stock.”

The Great American Cone Works sold ice cream served in hand-rolled cones from 286 Columbus Avenue in the early 1980’s. It was replaced by Big Steve’s Ice Cream by 1985. Disaster struck on the night of October 24 that year. The New York Times reported on “a woman” who joined the “long line of ice cream addicts” that night. She had her heart set on a scoop of cookeo flavor. The article said “her hopes were cruelly dashed by the harassed young man behind the counter. ‘Hey, I hope everyone here knows that we only have peppermint! And I can’t even guarantee you’ll get that!'”

“The cookeo woman went ice cream-less into the night,” said the article. Manager Robert Terhune explained that the shortage happened because the store stopped making its own ice cream on site and was getting it from other Steve’s stores. “He promised it wouldn’t happen again.” Apparently, the store fulfilled the promise and it remained in the space at least through 1991.

Other stores in the late 20th century included The Last Wound-Up, a toy store featuring reproduction wind-up toys; Il Cantone Restaurant and Wine Bar in No. 294, and Forza clothing store in 288.

Actress and model Cindy Guyer opened the “elegant” restaurant, as described by The New York Times food critic Florence Fabricant, Guyer’s in No. 286 in 2016. In 2020 the sushi restaurant Kissaki partner with Guyer’s to share the space.

In the meantime, a renovation completed in 2007 enable a duplex apartment to be created on the fifth floor and the new penthouse level, unseen from the street.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

286 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 286 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Arthur Rubinoff!

Meet Garry Kanfer!