Tough Customers at The Westport

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

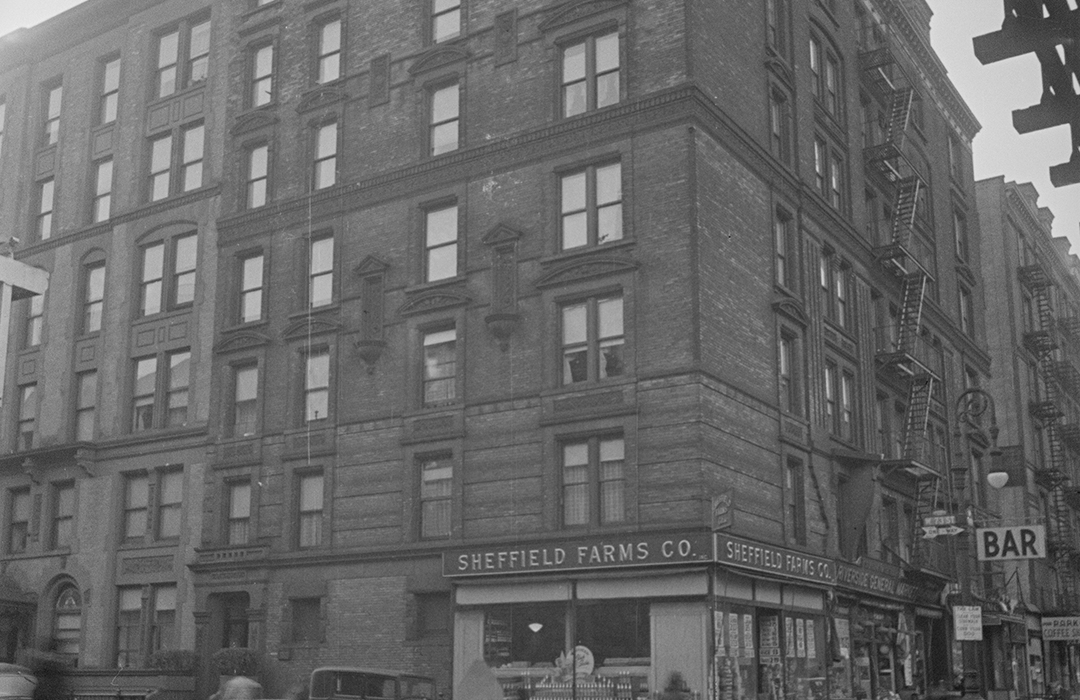

Charles Buek most often acted as the architect for the houses and apartment buildings designed for his development firm, Charles Buek & Co. that was the case in 1888 when he started work on The Westport at the southeast corner of Ninth (soon to become Columbus) Avenue and 73rd Street.

Completed the following year, the seven-story structure was a medley of architectural styles—Renaissance Revival, neo-Grec, and Queen Anne. Chunky, undressed brownstone blocks created the piers between the shops along the avenue, above which the six stories of yellow brick were trimmed in ruddy colored terra cotta.

The stores catered to the needs of the quickly expanding neighborhood. The T. W. Deck & Sons Morrisania Milk Dairy was in 269 Columbus Avenue, touting itself as “producers and dealers in Pure Milk and Cream.” Next door was John Hiscox’s fish market, and the Otten & Flagge grocery store was in 273 Columbus Avenue.

The apartments each contained eight rooms and a bath. Residents entered around the corner at 48 West 73rd Street. They were professional and respected, like the Rev. Henry Evertson Cobb, among the initial tenants, who was minister of the West End Collegiate Church.

Although newspapers generally reported on the residents’ dinner parties and marriages, it was a more shocking set of incidents that landed Bessie Thompson’s name in the news. She was friends with Barbara Clarrage whose husband, Frederick, had walked out on her, leaving her with no means of support. A warrant for his arrest was filed, but the 38-year-old Frederick “was wily and kept out of the way,” according to The Philadelphia Inquirer on February 14, 1894. But his 30-year-old wife was wily, herself, and came up with a scheme.

Barbara Clarrage visited Bessie in her Westport apartment and unveiled her plan. Bessie placed an advertisement in the personal column of a newspaper, which said “that the advertiser had been smitten with Clarrage’s attractions and would like to get acquainted with him,” as reported by The Philadelphia Inquirer. Frederick took the bait and made an appointment for 8:00 on the evening of February 13. Lurking in the shadows was Policeman Billan. When Bessie recognized her friend’s husband, she walked up and took his arm. It was the signal for Billan to pounce. Clarrage was arrested and ordered to pay his wife $4 per week.

All well-to-do, the residents of The Westport had domestic staffs. In the spring of 1898 one of Evelyn Murray’s servants placed an order at the fruit store of John S. Gandlfo (described by The New York Times as “a young Italian”) at 352 Columbus Avenue. But the order was never delivered. And so, on the morning of April 2, 1898, “she drove up to the fruit store in a hansom and indignantly demanded of Mrs. Gandalfo, who was in charge, why an order for 58 cents’ worth of mushrooms and a pear had not been sent to her apartment.” Mrs. Gandolfo could find no order but said she would send the order at once. The New York Times said, “This so mollified Mrs. Murray’s wrath that she ordered 50 cents’ worth of oranges, saying she would pay when the goods were delivered.”

The Irish delivery boy, John McCaffrey, took the basket of fruit. When he got to the top of the stairs, Evelyn Murray was impatiently waiting. She “took the goods, criticized the mushrooms and the pear, declared there was nothing like 58 cents’ worth, and proceeded to take as many of the oranges as she thought would make the difference,” said the article. Although McCaffrey protested, he was kept at arms’ length by the Murray’s butler, “the latter being armed with a formidable club.”

Picking up a stiletto and taking the Irish boy with him for support, he ran to The Westport. He bounded up the stairs and when no one would respond to his banging on the door, he broke it open with his shoulder.

McCaffrey returned to the store and told his employer how “he had been despoiled.” John Gandalfo vowed vengeance. Picking up a stiletto and taking the Irish boy with him for support, he ran to The Westport. He bounded up the stairs and when no one would respond to his banging on the door, he broke it open with his shoulder. “The butler was back of the door with a club, and young McCaffrey got the full force of it on the head,” said The New York Times, “and he was out of the play.” Gandalfo demanded full payment or the oranges and the butler “made argument with the club.” Evelyn Murray’s screams drew Policeman Dolan. The evidence of the broken door forced him to arrest Gandalfo for breaking and entering. “The Italian says there is no justice in the land,” reported the newspaper, “and declares he would have either his money or his oranges had the incident happened at his home in Sicily.”

John Hiscox was still operating his fish market downstairs. In October 1899, he, too, was forced to deal with a temperamental and disgruntled customer–the musical actress Sadie Martinot. She was well-known among New York audiences, having begun her career at the age of 15 and was the first to play the role of Herbe in an American production of H. M. S. Pinafore. According to The Morning Telegraph on October 12, “Miss Martinot has in her employ an elderly butler who is not too active either mentally or physically.” The article explained, “One morning not long ago Miss Martinot awoke to the realization, as actresses sometimes do, that she had no small change in the house with which to pay for messenger boys, automobiles and the other small necessaries of an actress’ life.”

She handed her butler, Charles, a $50 bill and instructed to have it exchanged for smaller denominations. Just as he left, he encountered James H. McAleese, John Hiscox’s delivery boy. Charles asked if he had change and the transfer was made. “At least,” reported The Morning Telegraph, that is what Charles says.” He went back into the house and handed his mistress two five-dollar bills. “Miss Martinot was naturally somewhat astonished, not to say perturbed, and she told the butler some plain truths concerning himself that may do him good hereafter.” She said she would hold him accountable for the loss, taking it from his wages.

She then headed to John Hiscox’s fish market with Charles in tow. There the teen insisted Charles had given him a $10 bill, for which he exchanged the two fives. “As a result of this conference,” said The Morning Telegraph, “Miss Martinot told Mr. Hiscox what she thought of fish dealers generally and of him in particular, and Charles, who made complain to the police, had McAleese arrested.”

Hiscox defended the boy, and the actress took the side of her butler. It ended up in court the following day where the judge dismissed the case for lack of evidence. “With much indignation Miss Martinot returned home and proceeded to strike fish from her daily menu, declaring at the same time a perpetual boycott against all fish dealers.” Sadie Martinot’s ire was no doubt heightened the following day when she was informed that a lawsuit for damages was being filed by the boy’s father “for causing the improper arrest of the fish dealer’s boy.”

At the turn of the century tenants in the eight-room apartments paid the equivalent of $3,000 per month rent in today’s money. They were affluent to afford not only the rent, but luxuries like automobiles, at least in the case of cotton broker James Reardon. It landed him in jail on a charge of reckless driving on August 17, 1905. The Evening Post explained, “Reardon’s car ran away from him on the [Williamsburg] bridge.” It crashed into a truck being driven by James Connelly. Happily for Reardon, in court the trucker said he decided the accident was unavoidable and he withdrew his complaint.

By now, 275 Columbus Avenue was a New York Central Railroad ticket office, and E. Carmin’s retail florist shop was in 269 Columbus Avenue. Among the tenants living upstairs were William Day Leonard and his wife, the former Florence Gibbons Kendall. Born in New Jersey, Leonard was a corporate lawyer and a director in several firms. The couple lived in The Westport apartment until his death here in 1916.

Another well-heeled resident at the time was the widowed Emma Ingraham, who shared an apartment with her daughter. Her income was increased in 1914 upon the death of her millionaire brother-in-law, Arthur Ingraham, a former banker. He left her a trust from which she received an annual income of $900—just under $25,000 today.

The family of Paul E. Lamarche lived in The Westport at the time. The wedding of their daughter, Ethel, in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in January 1917, was of note to society. The groom was John Eyre, son of the late John Eyre “of Lima, Peru, and Valparaiso, Chile,” as reported by Brooklyn Life. In the large bridal party were seven ushers and two flower girls. A reception in the Lamarches’ apartment followed.

Emma Ingraham and her daughter were still here in 1921 when they placed an advertisement to rent two rooms. On April 12, a man knocked on the door asking to see them. Emma let him in, showed him the rooms, and he told her “I’ll take one and I have a friend who will take the other.”

They discussed the rent, and as he prepared to leave, he paused and asked for a glass of water. Emma started down the hallway and just as she entered the kitchen, he struck her over the head with a blackjack. She fell to the floor where he hit her a second time, knocking her unconscious. The man took a $500 ring off her finger and left the apartment. When she awoke about 15 minutes later, she screamed for help. The superintendent and his wife rushed up the stairs and found her on the kitchen floor. A physician later called her injuries “serious.”

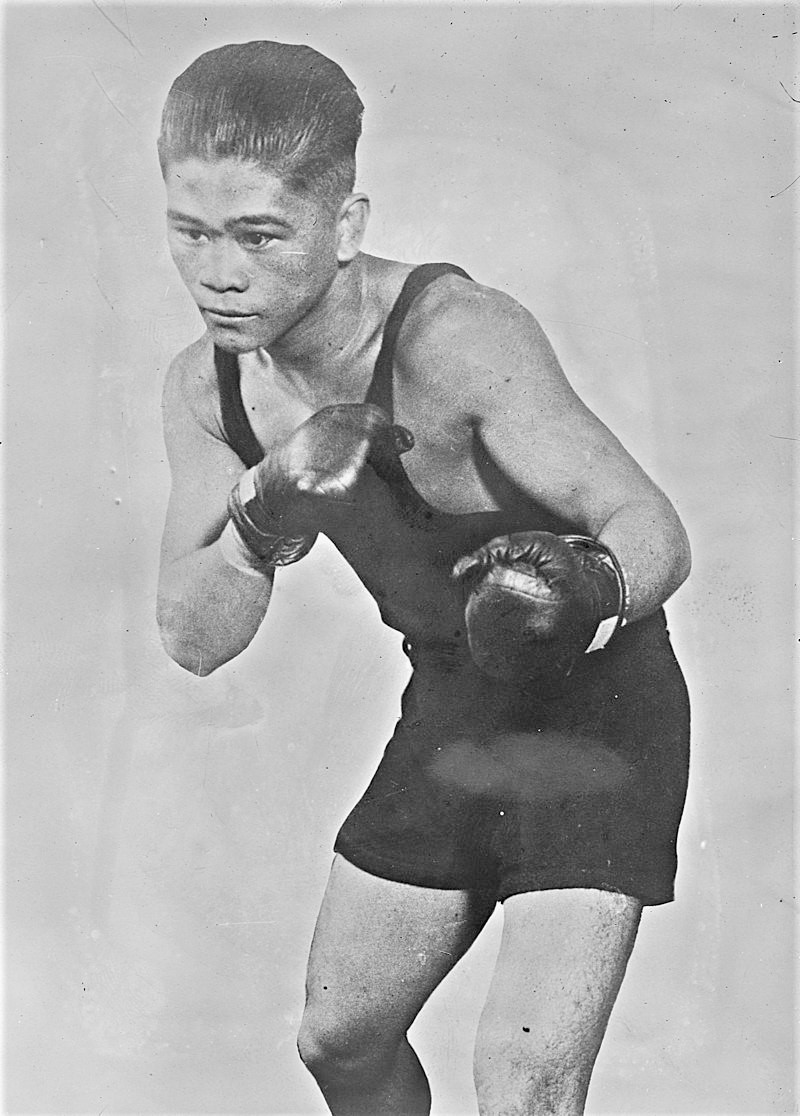

A perhaps unexpected resident was Pancho Villa, the Filipino professional boxer. He was arrested on November 5, 1922 for driving without a license. At the stationhouse the policemen doubted his story that he was the flyweight champion of the United States and suspected that he had stolen the automobile, which was registered to Frank Churchill.

The sergeant challenged him to a boxing match in the police station to prove his story. “After three rounds the sergeant took off the gloves and declared that his diminutive opponent must be a champion,” reported the New-York Tribune. Frank Churchill, as it turned out, was Pancho Villa’s trainer and all suspicion of auto theft was dropped. “The charge of driving without a license remained, however,” said the article.

The sergeant challenged him to a boxing match in the police station to prove his story. “After three rounds the sergeant took off the gloves and declared that his diminutive opponent must be a champion,” reported the New-York Tribune.

Fred Moriarity shared an apartment with George Duffy in 1930. The two were both “soda dispensers” and both 24-years-old. Late on the night of May 19 Moriarity brought home a girl, 20-year-old Helen Wainer, whom he had known for about two weeks. According to Duffy later, they came in around 1:15 in the morning, “quarreling bitterly.” He left the room and when he returned a few minutes later they were gone and a window was open. “Looking out, he saw them on the roof, twenty feet below,” reported The New York Sun. According to Moriarity, Helen had tried to “hurl herself” from the fourth-floor window. In trying to stop her, he lost his balance and they both plunged to the roof of the adjoining building. Both survived although Helen suffered a possible fractured skull.

Two decades later another bizarre fall occurred. This time Martin Conway was arrested for felonious assault for tossing his eight-year-old son, Donald, out of their third-floor apartment window. Conway, who was 39 years old and struggling to find work, denied the charges. His terrified son, his left foot and leg encased in a plaster cast, appeared in court on July 19, 1950. Although he had initially said his father had hurled him from the window, he now changed his story.

“I fell out the window. My daddy was asleep,” he told the Assistant District Attorney. He said that “no one had told him to say he fell out the window.” The case had to be dismissed, much to the disgruntlement of Magistrate Strong. He told Martin Conway, “There were only two humans in that room. On the evidence this case cannot be prosecuted in court, but God also was there. If you did throw your son from that window you will pay for it in the end.”

Two other Irish immigrants, Maurice Keane, who came from County Carey, and his wife, the former Nan O’Donnell, lived in the building in the early 1960’s. Maurice died in the apartment on August 11, 1964.

In 1967 a renovation resulted in six apartments per floor. Three years later Irish-born Mike and Patrick O’Neal opened O’Neal Brothers restaurant in 269 Columbus Avenue. According to New York Magazine on May 25, 1970, “O’Neal Brothers still belongs to the [neighborhood] old-timers by day, but at night it gets the nouveau West Siders, the literati and those who expect Dijon mustard, skinny, truly French french fries and fresh flowers.”

On September 17 the following year, fire broke out in the kitchen of O’Neal Brothers at lunch time. The blaze traveled upward, gutting two apartments. Others were extensively damaged by water and smoke. Two dozen fire fighters were treated at hospitals, mostly for smoke inhalation. O’Neal Brothers rebuilt and remained in the space at least through 1976.

O’Neal Brothers gave way to Ruppert’s Restaurant. In 1985 Ruppert’s closed, and Forza restaurant moved in. The tradition of eateries in the space continued with The City Grill in 1997, the Columbus Tavern, and most recently a Starbucks. Zucker’s bagel shop occupies 271 today; and the stores at 273 and 275 have been combined for The Flying Fisherman restaurant, which has become Harvest Kitchen.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

269-275 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 269-275 Columbus Avenue: