Uncle John’s Doll Hospital

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

In 1886 the real estate development firm John Farley & Son completed construction on two back-to-back, mirror image apartment buildings that engulfed the western blockfront of Columbus Avenue from 70th to 71st Street. Designed by the architectural firm of Thom & Wilson, the Renaissance Revival style structures were heavily influenced by the currently popular neo-Grec and Queen Anne styles.

The residential entrance to the southern building was located around the corner at 101 West 70th Street atop a three-step stone stoop. The commodious apartments had six rooms and a bath. Stores lined the ground floor along Columbus Avenue.

The residents were financially comfortable professionals, like Dr. Matthias L. Foster. In July 1887, he was among the 50 physicians appointed by the Board of Health to the Tenement House Corps. Each served two months and made visits to the crowded and often unsanitary tenements. The appointment, which was subsidiary to his private practice, came with a salary of $100 per month. Dr. Foster addressed medical audiences, like his June 28, 1888 lecture on Syphilitic Otitis at the New York Polyclinic Hospital.

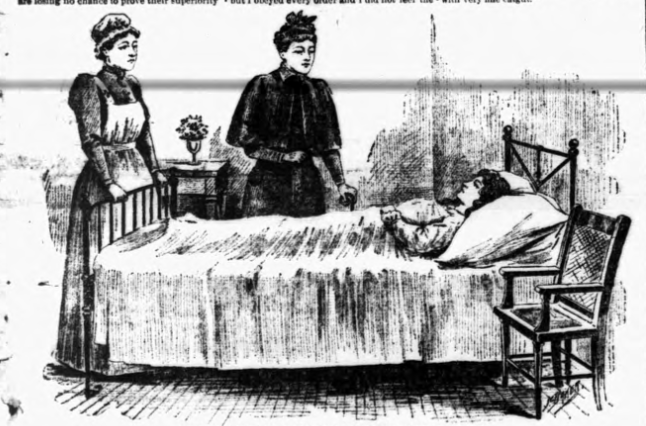

All the tenants had a small domestic staff. Mary Hooker was “a maid of all work” in the apartment of A. L. Doll on the third floor in 1893. She was described by the New York Herald as “a short, plump little body, twenty-three years old.” On the afternoon of November 26, she was having trouble closing the sliding door of the dumbwaiter shaft. The New York Herald reported, “she mounted a chair to pull down the slide. Her hands slipped and she slid feet foremost into and down the shaft.” Mary plunged three floors to the cellar, landing in a sitting position. The force had broken three vertebrae.

Mr. Doll heard the noise and rushed to the cellar to find her. She was taken, still in a sitting position, to the New York Polyclinic Hospital where a delicate operation was performed. Four splinters of bone were removed, one of which nearly touched the spinal cord. Following the operation Mary was put in a full body cast.

The famous female journalist Nellie Bly visited Mary Hooker on December 2. Her feminism showed itself in the opening lines of her article: “When a man loses his backbone he becomes an object of scorn. Of course, it was left to a woman to show the world how to lose a backbone and become famous thereby.”

The original tenant of the corner store Herman L. Behren’s pharmacy. Behren lived nearby at 180 East 70th Street and would operate the drugstore into the 20th century. On the opposite end of the row, at 228 Columbus Avenue, was John Lamb’s doll repair shop.

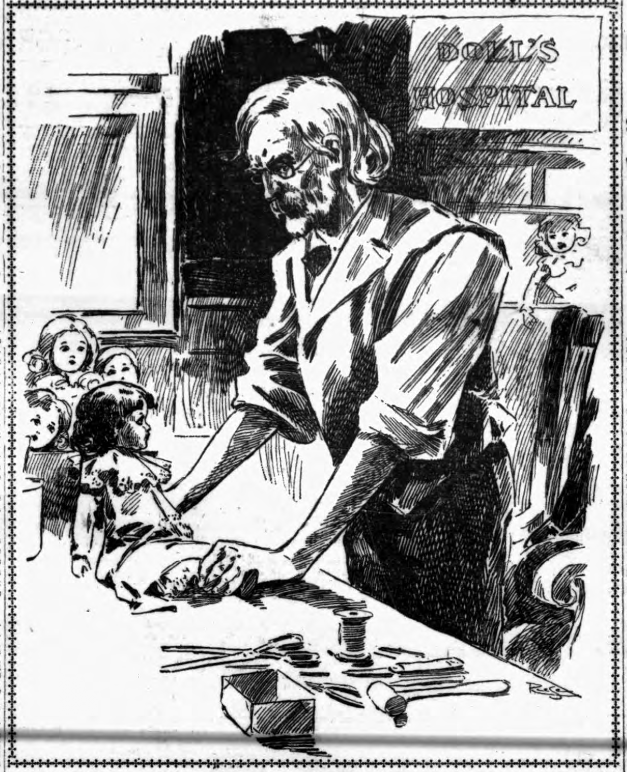

John Lamb had immigrated to the United States from Ireland in 1840 and, according to The Sunday Telegraph in 1900, “since that time has followed the occupation of splicing broken limbs and fractured heads of dolls.” Lamb became known as the “doll doctor of the West Side” to grown-ups and “Uncle John” to the children.

The World described his “doll hospital” as a place where “fractured limbs of dolls were repaired, flaxen hair reglued, broken heads restored and limp bodies refilled with sawdust. A screw here and a patch there, and he dexterously restored a talking doll’s vocal organs to their full power.”

When one of his sons went to open the shop at 9:00 the next morning, he found his father dead at his bench, the broken doll in his hands. The World reported, “The physicians found that the gentle heart had stopped beating.”

His shop was often filled with children, The World saying, “He bore a genuine love for his little patrons and was happiest when surrounded by a group of them, listening patiently to their sorrows, but always sending them away buoyant and laughing.”

On August 17, 1900, a little girl arrived at Lamb’s shop “holding by a limp arm a doll much the worse for a fall from a nursery window on the fourth floor,” as reported by The World. “She feared her dolly would die.” Lamb took her on his knee and promised he could fix the doll by the next morning. To do so meant he would have to remain at work late that night.

Lamb did not return home that night, but neither his wife nor his four grown children who lived with them were concerned. He had told them he would possibly stay overnight in Brooklyn with a friend. When one of his sons went to open the shop at 9:00 the next morning, he found his father dead at his bench, the broken doll in his hands. The World reported, “The physicians found that the gentle heart had stopped beating.”

Bernard A. Fielding, his wife, and son Harold lived on the second floor around the time. Domestic problems developed and the Fieldings separated in 1904. Harold, who was 21 years old, was greatly distressed at his parents’ breakup and, according to the New York Herald, begged his father to reconcile. Harold worked for the United States Casualty Company and was “a prominent member and marksman of the Seventy-first Regiment.” As Christmas approached, Harold was certain the holiday would soften his father’s heart. He wrote him a letter asking him to come home. But he did not.

Mrs. Fielding became concerned over her only son’s despondence and asked him several times to give her his revolver. He promised her he had no intentions of hurting himself. On the night of December 26, she went to bed at around 10:00. The New York Herald reported, “a few minutes later Harold entered the bathroom of the apartment, carrying a revolver, in which there was only one cartridge. Standing in front of a small mirror, he evidently placed the muzzle of the weapon to his right temple and pulled the trigger.”

Mrs. Fielding was still living in her second-floor apartment with a live-in maid, Nellie Edwards, in 1908. Among the top floor tenants were the widowed Jennie Landon, her grown daughters, Margaret, Annie, Jennie and Hannah, and a cousin, Andrew J. Dillon, whose wife had recently died. With him was his three-year-old daughter, Margaret. On the night of February 6, fire broke out in the cellar. By the time it swept through the building and reached the top floor, it was an inferno.

Margaret Landon, who was 22 years old, awoke to find her room on fire. The Evening World reported, “She awakened her mother and sisters, and then Mr. Dillon. She grabbed the Dillon child in her arms and made for the hall door, calling for the others to follow. As she opened the door flames drove her back, and she dashed for the fire escape overlooking Columbus Avenue.”

Margaret’s shouts had awakened other families. Mrs. Fielding and her maid tried to escape through the hallway, accompanied by her neighbors the John Howard family. Driven back by the flames they clambered onto the fire escape. But the lower ladder was raised and “they remained there, blocking the way of those above,” said the article.

Among those trapped was Mrs. William Anderson and her three boarders, including Chuan Lok Wing, the Chinese Vice-Consul and his wife. And the Landons family had no way of escape either. “The fire on the top floor was getting hotter and hotter,” said the New York Herald. Margaret’s desperation worsened. She said, “If the engines don’t come soon, I will jump.” Just as Andrew Dillon took his daughter from her arms, Margaret plunged to the street, dying instantly.

Chuan Lok Wing also jumped, sustaining severe internal injuries. More than two dozen residents were hurt “and there would have been more deaths had not the daredevil firemen come along,” said the New York Herald. “They carried a lot of women and children down their ladders when it looked as though they were running through fire walls.”

Chuan Lok Wing had arrived in New York in 1866, one of 200 young men sent by the Chinese Government to be educated. He was called back to China a year later, but he returned, this time his parents paying his expenses. He never went back and became a U.S. citizen. He graduated from Yale in 1883 and, according to the New York Herald, “was thoroughly Americanized.” In 1893, he married an American girl, something which did not please some traditional Chinese. Too, he made serious enemies among the New York Chinese community for his opposition to “the tong spirit”—or gangs—that terrorized Chinatown. Additionally, said the newspaper, “His advocacy of American methods and customs also made him unpopular with some of his law-abiding countrymen here.”

Wing was still partially recovering from the injuries he suffered in his jump from the fire when on August 1, 1909 a young man named Wong Bow Cheung walked into his office and shot him in the back. He died a few hours later.

After the fire, the corner pharmacy had become Herman Carr’s hardware and electrical fixtures store. For a time on December 5, 1912, it looked as if he, too, might have to relocate. Fire again broke out in the cellar and The Evening World reported “the volume of smoke was so great that all of the tenants of the house had to rush down the fire escapes or take their chances on a long leap from the roof to an adjoining one.”

The smoke had first been noticed by a patrolman who, with four others, rushed through the building banging on the doors with their night sticks to wake the tenants. Joseph Miller, his wife and five children, one an infant, ran to the roof. Police Officers Feeley and Balbert jumped 15 feet down to the roof of the adjoining building on 70th Street where, one-by-one, two other officers lowered the Millers by their hands to them.

In the meantime, publisher Charles A. Condin and his wife started down the fire escape ladder, Condin carrying their bulldog. At the third floor, Mrs. Condin lost her footing and started to fall. Condin had to drop the dog “to put out his arms and stay his wife’s fall,” said The Evening World. “The dog fell forty feet and broke two legs. He had to be shot by one of the policemen.” To make things even worse, when the Condins returned to their apartment, they found that someone had stolen $700 worth of jewelry and clothing.

Happily, unlike the fire four years earlier, this time no one was seriously injured. The Evening World reported that the fire “was quickly put out with a loss of $2,500.” (That would amount to about $68,000 today.)

The newspaper recounted, “The door was opened and the trio burst in.” Later in court McGowan testified, “Mrs. Compris could not restrain her anger upon seeing Miss Scott, who was reclining on a couch in her nightie, with her hair hanging down her back in two thick braids, while Mr. Compris was standing by in pink pajamas.” Not surprisingly, May Compis was granted a divorce on April 13, 1916.

Following the repairs, the six-room apartments rented for between $40 and $45 per month—the higher rate equivalent to about $1,200 today. Among the new tenants was mural artist Maurice Compis and his wife, May E. Compis.

Compis was born in Amsterdam in 1885, eventually immigrating to the New York where he established himself as a muralist and furniture design. He painted portraits and still life subjects on the side. By the time, the couple moved into their apartment here, he was among a well-known muralist, doing work in some of the mansions of Manhattan’s wealthiest citizens.

In 1915 May became suspicious that “Miss Claudia Scott, an actress, was more to Compris than a model for his well known conception of ‘Dawn,’” as reported by The Evening World. She engaged the help of a good friend, architect John C. McGowawn of the firm McKim, Mead & White, to stake out her husband’s studio. The Evening World said he “forsook his architectural duties and kept up a three months’ night and day vigil.”

In September 1915, McGowan saw Compris escort Claudia Scott from the stage door of the theater where she was playing to his studio. He telephoned May who, with a friend Katherine Haines, met McGowan outside the studio.

McGowan knocked on the door yelling, “Telegram for Compris.” The newspaper recounted, “The door was opened and the trio burst in.” Later in court McGowan testified, “Mrs. Compris could not restrain her anger upon seeing Miss Scott, who was reclining on a couch in her nightie, with her hair hanging down her back in two thick braids, while Mr. Compris was standing by in pink pajamas.” Not surprisingly, May Compis was granted a divorce on April 13, 1916.

Following the end of Prohibition, the corner store became the Excelsior Restaurant. It remained at least through 1953. By the early 1970’s M. Pappas restaurant was in the space, replaced in 1977 by Ying, a Chinese restaurant.

Le Yogurt, a restaurant featuring yogurt-based dishes like lemon-cucumber soup, was opened by fashion designer Joyce Moy in 224 Columbus Avenue in 1976. At 228, where John Lamb had once conducted his doll hospital, the coffee store The Sensuous Bean opened in 1979, replaced by the lingerie store Beauty Saloon in 1981.

The 1990’s saw Coco & Z, a “playful kids’ clothing” shop in 222, the Stockholm Restaurant in 224, and another children’s shop, Tvilling, in 228. More recently Salon Gabor operates from 220, The Muffins Café has been in 222 since 1997, Le Petite Kids is in 224 and Trollbeads, which was in 226 until the pandemic closed it in 2020.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

220-228 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 220-228 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Nicole Paynter!

Meet Ruth and Scott Bienstock!

Meet Kee Ling Tong!