Breaking the Mortgage Broker

by Tom Miller, for The Cultural Immigrant Initiative

Among the real estate developers active in the Upper West Side in the late 19th century was Sarah J. Doying. Real estate was one of the few male-dominated industries in which women could hold their own—assuming they had the money and acumen to do so. In 1886, Doying purchased the northern half of the Ninth Avenue (later Columbus Avenue) block between 69th and 70th Streets, and hired the architectural firm of Hubert & Pirsson to design three flat (or apartment) buildings.

Completed the following year, the five-story structure on the southeast corner of 70th Street was nearly identical to its neighbors. Clad in red brick and trimmed in limestone, its overall neo-Grec design was peppered with elements of the popular Queen Anne style. Two stores, one facing the avenue and the other on 70th Street (next to the residential entrance), provided the owner extra income.

The middle- to upper-middle-class tenants lived comfortably; many with a live-in servant. They occasionally appeared in the society columns. Such was the case on April 13, 1890, when The Press announced, “Mrs. Pupin of 68 West Seventieth Street gave a dinner party April 90. There were twenty persons at table.”

Typical of the residents at the time was the well-to-do Irish immigrant, Michael Sherry. His was an American success story. Born in Monaghan County, Ireland on February 14, 1837, he was three years old when his parents moved to Prince Edward’s Island. Shortly afterward, his father died. Sherry’s widowed mother brought her children to New York City in 1843. Michael Sherry became an office boy, and then in 1857 he and his brother Daniel opened a real estate office. By the time the life-long bachelor moved into his apartment here, he owned around 100 Upper West Side buildings and was, according to The New York Times, “one of the oldest real estate dealers in this city.”

By the time the life-long bachelor moved into his apartment here, he owned around 100 Upper West Side buildings and was, according to The New York Times, “one of the oldest real estate dealers in this city.”

Edward Hogan, described by The World as “tall, well-appearing” young man, moved in around 1893. He was a clerk—a catch-all term that ranged from a lower-paid office worker to a highly-responsible banking official. Without a doubt the other residents were shocked when, at 4:00 on the morning of New Year’s Day, police stormed into his apartment. The World reported, “Hogan was arrested in bed.” When they searched the apartment, “They found there a large quantity of stolen property.” Earlier, George Ellis, “the elegantly attired and polished young burglar,” had been arrested for the $5,000 burglary of August V. Lambert’s jewelry store on December 4.

At the station house, Hogan confessed with having received some of the jewelry, but “declared that he was innocent of any conspiracy with the burglars, according to the New York Herald. “He said he had never seen Ellis before, and that when the jewelry was brought to him to dispose of, he did not suspect that it had been stolen.” Police found his excuse hard to believe and The New York Times reported, “Hogan was arrested as a fence.”

Like Sarah J. Doying, Mrs. E. S. Conkling, who lived here by 1895, dealt in real estate. The Real Estate Record & Guide described her as “an extensive real estate owner and successful operator.” That success had come, in part, through heartless business practices. The Sun reported on December 31, 1895, “On one occasion… Mrs. Conkling, a wealthy woman up town, wanted some one to foreclose a mortgage for her on some property in Brooklyn. It was a particularly unpleasant bit of business, as the house in question was occupied by a poor family who had struggled hard to pay off the mortgage.”

After questioning acquaintances, Mrs. Conkling found a man, Albert A. Nellis, who was willing to do the untidy job. Afterwards, he became Mrs. Conkling’s regular collector. He and his wife purchased a house from her, and she provided the $20,000 mortgage.

The formidable Mrs. Conkling and Nellis had a particularly unpleasant parting of the ways. At one point Mrs. Conkling’s son, who lived in the Hotel Marborough, became ill and she went there to nurse him. Nellis made frequent visits there to see her on business. One night she was seen by the hotel detective in the corridor talking with him. He took her aside and asked if she knew Nellis was an ex-convict. The Sun reported, “She said she couldn’t believe it, and the hotel detective called a Police Headquarters detective, who corroborated his statement.”

Mrs. Conklin fired Nellis on the spot and as he turned to walk away, she asked if his wife was aware of his past. “When Nellis said that he had not, Mrs. Conkling told him to go and get his wife and have her back to the hotel within thirty minutes, or she would publish him all over New York as a thief and ex-convict.” Half an hour later Nellis was back with his wife. Mrs. Conkling said to her:

Has your husband told you his record; has he told you that he was a second-story thief; that not so many years ago he was caught walking out of a house with a bag containing $62,000 worth of bonds that he had stolen; that he pleaded guilty in court and was sent to State prison for five years?

The Sun reported, “Mrs. Nellis said that she didn’t believe it, and then fainted. Nellis revived her and took her away, and Mrs. Conkling has not seen either of them since.”

Mrs. Conklin fired Nellis on the spot and as he turned to walk away, she asked if his wife was aware of his past.

James S. Leibing came home to his apartment on March 3, 1922 to find it ransacked. The Evening World reported that “about $1,000 worth of jewelry [was] stolen.” Within hours the four youthful burglars were captured, the oldest of them being 20 years old.

Professional featherweight boxer, George Sanchez, lived here at mid-century. The promising fighter was 23 years old when he was in an automobile accident while living here in 1950. Although others in the car were injured, Sanchez emerged unhurt.

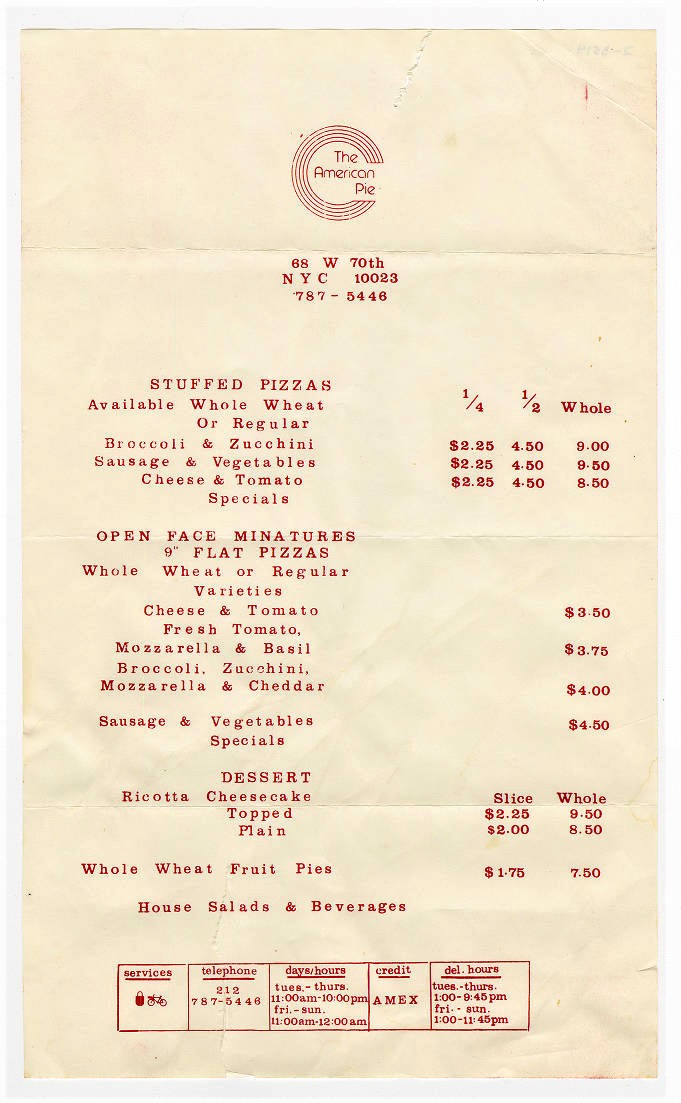

By 1983, the American Pie opened in the store on the side street. An off shoot of Aiello’s Pizza Emporium on Second Avenue, it caught the attention of The New York Times food critic Florence Fabricant. On February 16, 1983, she wrote, “White or red clam sauce pizzas are made here on thin, crispy crusts and sell for $1.30 a slice, $10 for a whole pie.”

Around the corner on Columbus Avenue was Anel French Dry Cleaners, owned by Leo Saltzman (who also owned the building). On September 13, 1986 The New York Times reported on artist Biaggio Gabriel DiGiovanni’s latest project—two 6 by 7 foot landscape murals on the side of the building. DiGiovanni, who lived in the building next door, explained it was “a birthday present to myself as an artist and to my friend Leo, who owns the building.” Saltzman chimed in, saying “Customers are crazy about it.”

DiGiovanni’s colorful murals have long since been painted over. And while the vintage signage for Anel French Dry Cleaners survives, inside is Aesop, a sleek Australian skincare boutique. The former pizza shop around the corner now houses a coffee shop, The Sensuous Bean.

The only surviving building of the 1887 row, 219 Columbus Avenue is a bit careworn and showing its age, but still features original wood windows.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

219 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 219 Columbus Avenue: