211-217 Columbus Avenue

by Tom Miller

Sarah J. Doying was among a handful of female real estate developers in the 19th century who thrived within the male-dominated industry. In 1886 she purchased the eastern blockfront of Ninth Avenue (later Columbus Avenue) between 69th and 70th Streets. She commissioned the architectural firm of Hubert & Pirsson to design six five-story flat-and-store buildings on the site, the corner buildings being half the width of the “inside” structures.

Completed the following year, they were clad in red brick and trimmed in limestone. The architects gave the overall neo-Grec design scattered elements of the popular Queen Anne style. The two northern “double flats” at 211-213 and 215-217 Columbus Avenue cost $14,000 each to construct, or about $468,000 in 2024 terms. Each had two stores at ground level, one on either side of the entrance.

The two apartments per floor in each building were marketed to middle-class families. An advertisement described, “Seven rooms; private hall and bath; steam heat; decorated; rents from $27; inducements.” The lowest rent would translate to about $935 per month today.

Living in the southern building in 1896 were Henry F. Luhrs, his wife Laura, and their two children: three-year-old Trixy and her three-month-old brother, Henry Jr. Henry was the superintendent of the Sloan’s stationery store on Columbus Avenue at 75th Street, and his wife had been a professional nurse before their marriage.

The Luhrs family were the victims of daring robbers on March 3 that year. Because Trixy had measles, Laura, who was described by the New York World as normally being a light sleeper, was up repeatedly during the night of March 2. However, the following night, at around 2 a.m., Henry groggily awoke to Trixy’s crying. Laura remained sound asleep. He got out of bed but “seemed to be unable to pull himself together,” as reported by the New York World. Uncharacteristically, it took him several minutes to arouse his wife. The article said, “She, too, complained of a dizziness in the head, and was unable to rise.” Laura turned on the light and exclaimed, “We’ve been robbed, Henry. See, the bureau drawers have been taken out and everything in the room is topsy-turvy.”

It soon became obvious that the criminals had sneaked into the bedroom and chloroformed the sleeping couple…

Indeed, not only was the bedroom ransacked, but so was the dining room. The burglars had taken the time to acid test the silverware, leaving the plated ware and making off with the sterling silver pieces. It soon became obvious that the criminals had sneaked into the bedroom and chloroformed the sleeping couple, allowing them to go through the valuables at their leisure.

In the meantime, the retail space at 211 Columbus Avenue was a dressmaker’s shop, while a “dairy store” occupied 213 Columbus Avenue. On September 30, 1898, an advertisement in the New York Journal and Advertiser read, “Saleslady wanted in dairy; arrangements with right party. 213 Columbus ave.”

The owner of the dairy store was in financial difficulties at the time. Later that year, Winfield H. Mapes, a dairy farmer from Orange County, New York, traveled to Manhattan “to collect a bill for a few cases of eggs shipped to a retail dealer at 213 Columbus Avenue,” as recalled by The American Produce Review years later. Instead of collecting the outstanding invoice, he ended up the owner of a store. The article said, “The dealer having no ready money, adjusted the account by turning the store over to Mapes.”

Unfortunately for Mapes, who took over the business on January 1, 1899, “there were eight inches of snow on the ground and one of the first duties was to deliver one hundred quarts of bottled milk to families in the immediate neighborhood. A pushcart made from a soap box mounted on baby-carriage wheels was the conveyor, with Mapes as the motive power. You cannot imagine a more homesick boy than he was that first week in New York.” (It all turned out just fine for Winfield H. Mapes. By 1922, he was head of the Winfield H. Maples Co., a major distributor of butter, eggs, and cheese.)

The northern stores were home to James Wilson’s pharmacy, at 215 Columbus Avenue, and the Tuxedo Market, a grocery store, in 217. In 1896 the Tuxedo Market (named for the fashionable resort, not the article of clothing) declared bankruptcy. Its new owners named it the Superba Market.

On Christmas night 1903, a huge fire broke out in the West Side Lyceum. The store at 213 Columbus Avenue was home to George I. White’s tailor shop, and he and his family lived in the apartment behind it. Just after 1:00 a.m., his daughter Jennie discovered that a fire had broken out in the cellar. The New York Times reported that White “ran to the fire engine house, in West Sixty-eighth Street, passing three fire boxes on the way.” Because of the West Side Lyceum blaze, there was only one firefighter at the station. A frantic series of alarms was initiated.

In the meantime, a messenger boy, J. Henry Weygandt employed by the American District Telegraphy Company’s office in 211 Columbus, jumped into action. He ran through the halls of both buildings, waking the tenants. The New-York Tribune wrote, “Eight families lived in each house, and there was great excitement, at one time almost a panic, among the tenants, who rushed forth, leaving goods and chattels behind.”

While fire equipment struggled along the icy, snowy roads to the scene (The Sun reported “it was twenty minutes before any engine arrived), heroic rescues were made. A plain-clothes detective named Isbell rushed to the top floor of 211-213 where he was told an invalid lived. “The detective carried her downstairs through the smoke,” reported the New-York Tribune, first warning her neighbor, Mrs. Gardner, who was in bed, ill, and her two children, that he would return for them.”

His actions were heroic. The article recounted,

“Save the children first!” pleaded the mother when he returned. One under each arm, Isbell took them and staggered down the stairs. Then groping his way back for the third time, he helped the mother down to the first floor, there, overcome by smoke and exhaustion, he collapsed.

The fire was eventually extinguished, but not before major damage was done to 211-213 and the stores were gutted. They were replaced by Wallach’s Laundry in 211 and K. Kuwayama’s Japanese Employment Bureau at 213 Columbus Avenue.

“You must be cold-blooded, Ma’am, if you’ll pardon my saying so…”

Charlotte Loder lived in 215-217 Columbus Avenue in the spring of 1905 when, while coming home from a shopping trip on May 13, she noticed what The New York Times described as “an old gray horse, weather-beaten, harness-worn, with three hoofs in the grave” hitched to a moving wagon in front of 169 Amsterdam Avenue.” The feisty Charlotte, who was described by the article as a “young woman, pretty and petite,” stopped and addressed the driver.

“Mister, I don’t know your name, you’re going to shoot that poor old horse.”

“Oh, sure,” he answered.

“Well, do it,” demanded Charlotte Loder.

“Oh, run along!” she was told.

And so, she did–right to the West 68th Street police station. She returned with Policeman Leggett and said, “Look at that poor old horse. Officer, I want to see it shot.”

“You must be cold-blooded, Ma’am, if you’ll pardon my saying so,” he said.

Charlotte, however, was on a mission. “I’ll see the captain. Officer, I charge that man with cruelty to a poor old horse. Bring him to the station.”

The entire party, Charlotte; the driver whose name was James Linden, with his cart and horse; and the policeman went to the station house. There Charlotte told the desk sergeant, “that man is driving a poor old horse that ought to be in a home for the blind, or whatever they call the horse home. It limps, and it breathes hard, and it groans. I want to see it put out of its pain.”

With tears streaming down her cheeks, she threatened, “He’s got to shoot it, or I’ll lodge a complaint. If he shoots it now, I’ll forgive him.” The New York Times concluded its article saying, “An hour later the horse was dead.”

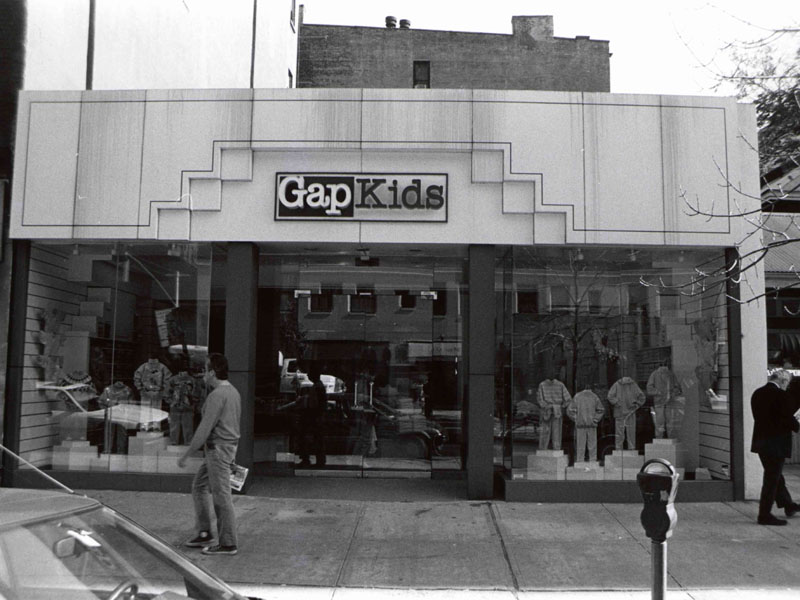

In 1940 the first floor of both buildings was gutted for a single occupant, a food market, which remained at least into the 1960s. Two later structures split the site, a Gap Kids to the north and a Banana Republic to the south. Somewhat surprisingly, the two buildings were demolished in 1987—leaving the rest of the 1886 row intact. In their place a one-story commercial building was erected, designed by Levikow Associates.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

211-217 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 211-217 Columbus Avenue: