Immigration: To and Fro…

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

On September 12, 1885, the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that Borkel & McKean were “about to erect five tenements on the northwest corner of Sixty-eighth street and Ninth avenue.” The wordage apparently offended the developers and two weeks later, on September 26, the journal apologetically announced, “We have since been informed that the houses on the avenue are to be first-class flats, with all the latest improvements, four stories, with stores underneath.”

The architectural team of Babcock & McAvoy designed the neo-Grec style apartment buildings to appear almost as a single structure. Each was five stories tall and three bays wide and held a store at sidewalk level. There were two apartments per floor in each building. The residential entrance to the corner building, 180 Columbus Avenue, was located around the corner at 101 East 68th Street.

Living in the corner building in 1893 was the family of Ernest Korn, a bookkeeper with the tea and coffee firm Benedict & Gaffney. His first wife had died and in February 1892 he married Fannie Waring, whose husband William Waring, had also recently died. She had two children, Edwin, and Florence. The New York Times described their second-floor apartment as “spacious” and “well-furnished,” saying they had “wealthy and well-known people for [their] immediate neighbors.” The family ate at restaurants, so Fannie did not have to cook.

According to The New York Times, “neighbors say that [Ernest’s] conduct was irreproachable. Whenever he came home late in the evening, he brought some dainty for the wife and children. He also frequently prepared the breakfast, the only meal that was cooked at home except on Sundays. They seemed to have an abundance of money and lived very comfortably.”

But Fannie began suffering debilitating migraine headaches in the fall of 1892. By the following spring neighbors noticed they were seriously affecting her. The New York Times reported, “One gossip said that Mrs. Korn’s faculties had been warped by her illness, and that she became jealous of her husband to such an extent that she would not tolerate the present of a domestic in the house.” It all came to a horrific end on the afternoon of May 5, 1893.

Fannie spent most of that morning sitting by the window writing letters. She then sealed them and called the children into the kitchen. According to 11-year-old Edwin later, “Mamma made up some medicine to give to us. She said it would be good for worms. We had been kind of sick. She made up two glasses of it. It was dark brown and burnt my mouth.”

The “medicine” was a home-made poison–a mixture of sulfur and phosphorous scraped from match heads, combined with water and flour. Edwin was old enough to have grown suspicious of the foul-tasking concoction and after his mother rushed from the room he hid under the table. When the poison did not seem to take effect, Fannie grabbed a pistol from the mantlepiece. When Edwin refused to come out, she shot blindly under the tablecloth. The boy screamed and ran out of the apartment. The Evening World reported, “Next she seized little Florence, and, after hugging the child in a paroxysm of love, shot the little one in the breast.” The six-year-old died almost immediately.

When the poison did not seem to take effect, Fannie grabbed a pistol from the mantlepiece. When Edwin refused to come out, she shot blindly under the tablecloth.

Hearing Edwin’s cries, the janitor rushed upstairs to find that Fannie had attempted suicide by shooting herself in the breast. She and Edwin were taken to Roosevelt Hospital where both recovered. Among the rambling letters she had written was one that said in part:

Oh! God, I hope, will forgive me for this, but I fear I can’t last much longer. It is a pity, as I have everything [my] heart wishes for, only not health or happiness, and I love my children so dearly I cannot leave them after me.

Fannie faced a judge and jury on July 28, 1893. The Evening World said, “She was clad in deepest black, but it could not add to the gloomy appearance of the haggard-eyed little creature.” She listened to her son testify to the events of that afternoon. The Evening World noted, “Mr. Korn was in court a most dejected man, watching with anxious, tearful eyes his unfortunate wife.” It did not take the jury long to come to a verdict—Fannie Waring Korn was insane at the time of the murder and not responsible for her acts. She was sent to the State Asylum for Insane Criminals at Matteawan.

In an interesting side note, on May 18, 1895 Fannie escaped from the asylum. She could not be located for two years, until on the morning of July 14, 1897 Policeman James McGrath—the same officer who had arrested her three years earlier—walked past her on West 47th Street. He turned around and caught up with her. He placed his hand on her arm and said, “Don’t you remember me, Mrs. Korn?”

She turned pale and said, “That is not my name.”

“Oh, yes, it is,” he answered. “You may as well admit your identity and come with me.”

Fannie, who had been making a living as a dressmaker, was returned to the asylum.

In the meantime, the store at 184 Columbus Avenue was originally leased to Goetz & Winter, “fine furniture and upholster.” Their advertisements promised, “draperies, lambrequins and curtains in latest designs a specialty.” Charles D. Goetz lived in one of the apartments above the shop and would remain at least through 1917. The same was not true of his store, however. By 1897 it was the grocery store of George Findlers.

Findlers kept a large cat named Tip in the store, most likely as a mouser. Early in the morning of April 17, 1897 Tip began nibbling on matches and set a stack of brooms on fire. A watchman saw the flames and called the fire department. “They broke a big plate glass window and Tip jumped into the street,” reported the New York Press. The fire was quickly extinguished. “The eight families in the house were awakened. There was no great excitement,” said the newspaper flatly.

By the turn of the century Findler had vacated 182 Columbus Avenue and the space became the Oak Farm Dairy, run by brothers George and John Fender. They advertised, “Best Butter, Pure Milk, Fresh Eggs, &c.” Their venture, too, would be short lived. In 1905 the store was purchased by Arthur Murture.

Murture was a Cuban immigrant who until recently had been in the cigar business. He had married his first wife in 1902 and they had two children, both of whom died. In September 1905 he walked out on his wife, sold his cigar business, and opened his Columbus Avenue grocery store. He later explained to a judge, “I lived with her until she began to nag. I believe God intended everyone to be happy, so I left her and married Miss [Bessie] Finn.” The problem was, of course, that Murture had not bothered to divorce his first wife.

He and both wives appeared in court on September 21, 1905. The told Magistrate Wahle, “I am willing to live with my wife if she will stop nagging.” The judge asked, “What about your other wife?”

“Oh, I do not know her very well and she will get along all right,” he answered.

Murture was ordered to pay his first wife $5 a week and was arrested on a charge of bigamy.

The store at 186 Columbus Avenue was originally a pharmacy, run by George E. Tappenden. It was purchased by druggist Arthur Fabisch in 1905. Next door at 188 Columbus was H. Tychsen’s candy and ice cream shop.

Above were respectable, middle-class working people like Edward H. Mullins, who was listed in 1894 as a journalist and in 1897 as an author. (He apparently lost his job at the newspaper.) Other tenants in the 1890’s included John Rohl, a piano maker; Henry A. Berthaume, a waiter, and his wife, Bertha, who was a dressmaker, and Augusta and Susan Windecker. Augusta ran a millinery shop nearby at 192 Columbus Avenue and Susan was a partner in Theiss & Windecker, the dressmaking shop on the street level. Other tenants were Edward H. Mullin, a clerk; plumber Thomas F. Burke; and John J. McKenna who ran a storage facility.

It appears that the Windecker women—or at least Susan—left New York for good in 1897. An advertisement appeared in the New York Herald on May 30 that year offering the shop for sale. She was looking for “a competent dressmaker to take charge of an established dressmaking parlor, with large trade; very small capital required; owner leaves for Europe, not returning.”

Rent was apparently quite affordable. Annie A. Smith lived here for several years in the beginning of the 20th century, living off the pension of her deceased police officer husband. She annually received the equivalent of $8,000 today.

Years later, German immigrants Adolph Wollschlager and his wife encountered severe domestic problems in 1909. Wollschlager had served in the German army and was a member of the Kriegerbund, a veterans’ association. The Syracuse Journal explained, “It was while he was serving as a bulwark to the Kaiser, he said, that he met his wife. The red and gold uniform and the clanking saber won her heart and when he said, ‘Will you wed?’ she replied, ‘I will.”

But in America her ardor cooled. Despite the fact that, according to The Syracuse Journal, he served his wife breakfast in bed, bathed her feet, and pared her corns and toenails, and even warmed her underwear at the stove before she got out of bed in the winter, it was not enough. She told him she was moving to Boston to open a boarding house and walked out. Instead, however, she took an apartment at 101 West 68th Street.

When his letters came back unanswered, Adolph “went a-sleuthing and found her finally at 101 West Sixty-eighth street,” according to the newspaper. He put on his regimental uniform, hailed a hansom cab and knocked at her door. When he heard his wife’s voice ask, “Who is it?” he replied, “It is I, your Adolph, he is here.”

A few days after the incident detectives arrested four men and recovered a platinum and diamond ring stolen from the fiancée of “Dapper Dan” Collins, described by the New York Evening Post as a “notorious international thief and confidence man.”

His announcement was met with silence. And so, he drew his sabre and “with a few well-chosen slashes cut the panel from the door.” The article went on, “Mrs. Wollschlager fled to the fire escape, and her screams attracted a crowd, and as Adolph dashed out of the house he was captured by a policeman.”

Wollschlager appeared in court dressed “in the gorgeous trappings of a member of the Kriegerbund,” said The Syracuse Journal. He pleaded with his wife to return to him. “It is enough what I say,” she retorted, “You no longer do I love.” Rather astonishingly, the judge dismissed her complaint against Wollschlager for breaking into her apartment. She then “flouted out of the court.”

Wollschlager’s store had become a delicatessen by the early 1920’s. It was the target of armed robbers in October 1924. But in the Roaring ‘20’s, when organized gangs ruled New York and Chicago, the deli’s owner was not especially eager to finger the perpetrators. A few days after the incident detectives arrested four men and recovered a platinum and diamond ring stolen from the fiancée of “Dapper Dan” Collins, described by the New York Evening Post as a “notorious international thief and confidence man.” The Evening Post reported, “A delicatessen dealer at 188 Columbus avenue failed to identify them in West Side Court today, however.”

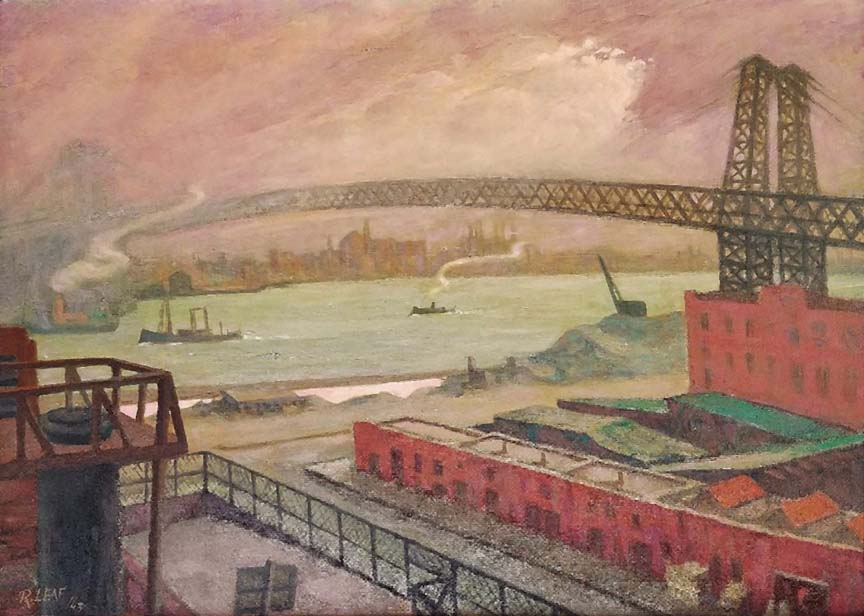

By 1929 artist Ruben Leaf (whose birth name was Lipschitz) had an apartment. He produced Jewish artwork for residences and synagogues and worked in several media including bronze from which he formed ceremonial and decorative items like menorahs.

In 1932, with Prohibition ended, as hotels scrambled to obtain their liquor licenses, new taverns opened around the city. Irish immigrants Tony Brown and Joe White opened the Brown and White Chop House in the corner space. Joe White was “one of Meath’s great football players,” according to the Irish American newspaper The Advocate. On January 6, 1934, the newspaper said White “is contemplating bringing out the Meath team from Ireland in May.”

Two other Irishmen, Patrick J. Cooney and John J. Healy, opened The Shamrock Bar & Grill in 188 Columbus Avenue in 1933. Both men were natives of Dunmore, Ireland, in County Galway. For some reason, three years later they moved it two doors down, to 184 Columbus Avenue. They held their grand opening party in January 1936. The Irish community newspaper The Advocate said the men were “delighted with its great success” and added that the Shamrock was “a splendid place to enjoy a nice evening.”

In the second half of the 20th century an additional store was added at 101 West 68th Street. It was home to the Pierette Dog Grooming Salon in the 1970’s before becoming a series of pizza shops—Freddy & Pepe’s Gourmet Pizzeria by 1985, Fellini’s pizza shop in 1989, and La Traviata Pizza, which survives, by the mid-1990’s. To the northern extremity on the avenue, Seattle Coffee Rosters filled 188 by 1995, followed by Gourmet Market and then Details, a stylish housewares boutique. The aughts saw Wink, a women’s fashion and accessories boutique in the space until 2015, followed by T2, an Australian tea shop featuring over 200 varieties of teas. 188 had a competing Tea Too.

Today the string of Columbus Avenue stores represents a variety of businesses—Moscot Eyeware in 188, two Italian eateries, Francesco Pizzeria and Il Violino in 186 and 180 respectively, and two clothing stores, Rag & Bone in 182 and Bluemercury in 184. The upper portion of the buildings are little changed since they were completed in 1886.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

180-188 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 180-188 Columbus Avenue:

Meet Daniel Vlasceanu!