A “Taxpayer” Full of Talent

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

The eastern blockfront of Columbus Avenue between 67th and 68th Streets saw initial development in the late 1870’s with small shops and brownstone houses. Lard merchant Anderson Fowler, principal in Fowlers Bros., got in on the act. In 1878 he commissioned Scottish immigrant architect brothers David and James Jardine, of the firm D. & J. Jardine to build five four-story brownstone dwellings on the northwest corner of 67th Street and Ninth (later Columbus) Avenue.

The investment came at a propitious time for Fowler, who would soon have to rely on his real estate holdings for income. Less than two weeks later, on September 6, he got into a noisy disagreement on the floor of the Produce Exchange with another lard dealer, William G. Shaw. When Shaw uttered, “My opinion is, you’re an impertinent cur,” Fowler “promptly knocked Mr. Shaw down,” reported The Sun. Four days later The New York Herald announced that Fowler “was suspended indefinitely.”

On September 6, [Fowler] got into a noisy disagreement on the floor of the Produce Exchange with another lard dealer, William G. Shaw. When Shaw uttered, “My opinion is, you’re an impertinent cur,” Fowler “promptly knocked Mr. Shaw down,” reported The Sun.

The houses were completed in the spring of 1879. On May 31 Fowler sold 45 West 67th Street to Lavinia Lowry for $26,000 (about $687,000 today). The other four became home to well-to-do families, as well, like that of Edwin B. Curtiss in 43 West 67th Street. Curtiss was an attorney and bookseller, as well as a director in his brother’s sporting goods business, A. G. Spalding Bros. He and his wife, Virginia, maintained a country home in Greenwich, Connecticut designed by Carrère & Hastings.

The block’s personality would change following the turn of the century when Mary E. Boyer acquired the property. Perhaps because she lived significantly far away in St. Louis, Boyer seems to have been unsure exactly what to do with the property—or she may have simply recognized that its value was certain to increase. In either case she hired architects Ernest Flagg and Walter B. Chambers to design a “taxpayer” on the property. Their plans, filed on June 19, 1903, called for a two-story brick “store and offices” building to cost just under $750,000 in today’s dollars. “Taxpayers” were most often low, relatively inexpensively built structures which provided enough income to the owners to pay the property taxes. They were frequently seen as relatively temporary as well, paying for themselves while permanent development schemes were finalized.

Flagg & Chambers produced a low red brick building with minimal stone decoration—a significant cost savings. Storefronts sat shoulder-to-shoulder along the avenue, while the oversized arched openings of the office level gave the building a nearly stable or train barn appearance. Above the bracketed cornice, was a handsome waist-high iron railing. The stores filled with a wide variety of businesses. J. T. Finn & Co., a substantial plumbing business operated from the second floor of 161 Columbus for years. Typical of its commissions the “steam and hot water heating system” it installed in Charles M. Schwab’s massive Riverside Drive mansion in 1904. Concerning that job Domestic Engineering commented, “All brass piping is being used.”

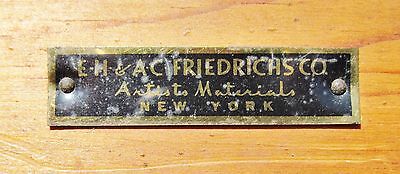

In the storefront directly below J. T. Finn & Co. was a much more glamorous business, Ward & Feld, ladies’ tailoring and furrier shop. Next door at 163 Columbus Avenue was the art store of E. H. & A. C. Friedrichs Co. A go-to store for artists, it supplied canvases, paints, painting knives and other necessities. By 1906 Calama Brothers Restaurant was in the corner location at 157 Columbus. Operated by Italian immigrant brothers Gustatus and Samuel Calama, it was a popular dining destination until about 1917 when it moved down the street to 146 Columbus Avenue.

In May 1904 Ward & Feld hired a “little blonde beauty,” as described by The Evening World, as a messenger. Women shoppers were not expected (nor did they expect) to carry their own packages home and the often-unwieldy gown boxes were therefore delivered. Fifteen-year old Elizabeth Jacobsen with her blue eyes and “flaxen hair” was the daughter of “well-do-to German people.” She presented herself well and seemed the perfect choice. Except she wasn’t.

A few days after Elizabeth started the job, she disappeared. So did a silk dress and cash—a total heist of about $2,370 in today’s money. Over the next few months a girl matching Elizabeth’s description answered ads for servant positions in fine homes. After a day or two working she would vanish with jewelry or fine clothing.

Detectives came up with a plan. May Dickey had been Elizabeth’s supervisor at Ward & Feld. They placed an advertisement for a servant at Dickey’s address, then waited in hiding as about twenty applicants showed up. Sure enough, Elizabeth rang the bell. She was promptly arrested. The shame was almost too much for her parents to bear. According to The Evening World on November 16, her father, who ran an apparel business, “is home in bed and the shock of his daughter’s arrest has completely prostrated him, so much so that his condition has become grave.”

Elizabeth rang the bell. She was promptly arrested. The shame was almost too much for her parents to bear. According to The Evening World on November 16, her father, who ran an apparel business, “is home in bed and the shock of his daughter’s arrest has completely prostrated him, so much so that his condition has become grave.”

In 1910 Henry M. and Mary C. Richardson ran their Costar Mfg. Co. and the Costar Vermin Exterminating Co. above E. H. & A. C. Freidrichs Co.’s art store. James A. Phillips, a contracting plasterer had an office here, as did the Wattson Rubber Co. That company hinted at the growing influence of the automobile industry. It was joined in the building in 1915 by the Pioneer Tire Company, and in 1920 the Manhattan Automobile Exchange had taken over the former Calama’s Restaurant space on the corner.

The Manhattan Automobile Exchange was the equivalent of today’s second-hand car dealerships. It used a clever, if slightly deceitful marketing ploy, the “little old lady” scam which became synonymous with unscrupulous auto dealers later in the century. Pitiful advertisements under the name of “Mrs. Germain” appeared in the automobile sections of newspapers, like the one on March 6, 1921 in the New York Herald offering a Cunningham auto for sale “account [of] financial difficulties, must be disposed of immediately. Mrs. Germain.” But only a month earlier an advertisement offered a “Scripps-Booth light six touring, in A-1 condition; must be disposed of.” Had a keen-eyed buyer looked closely, he would have seen another ad on the same page “Wanted—5 or 7 passenger touring or sedan, 157 Columbus av.”

By 1942 the Manhattan Automobile Exchange had vacated the corner store and it was home to The Thomas Pharmacy, which proudly announced its Luncheonette in advertisements. Freidrich’s art shop, after nearly three decades, was still in the building, now home to other businesses like a hardware and a furniture store. If Mary E. Boyer had intended to develop the site with a more substantial building, it never happened. Her will bequeathed it to St. Louis University. Then, on July 20, 1949 The New York Times reported that the “two-story taxpayer” had been sold to the newly-formed 161 Columbus Avenue Corporation. It appeared that the end of the line for the low building with its jumble of stores was near. But it survived another five years. On January 13, 1954 The Times ran the headline “Taxpayer Bought On The West Side” and noted that “a parking lot adjoining on Sixty-seventh Street was included in the deal.” Technically, that property was not a parking lot, but a lumber yard.

The 1903 Flagg & Chambers building was demolished for an attended parking lot which could accommodate 66 passenger vehicles. The valuable property sat underused as a parking lot until 1983 when father-and-son development team Nathan and Daniel Brodsky announced plans for a 32-story condominium designed by Schuman, Lichtenstein, Claman & Efron with interiors by Robert Cane of Buck/Cane Architects.

2021: Unleashed has become Sweetgreen; GNC will soon become Starbucks; Fresh is for rent.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

157 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the businesses currently at 157 Columbus Avenue:

NOW OPEN!

NOW OPEN!

COMING SOON!