The Columbia Storage Warehouse

by Katherine Taylor-Hasty, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

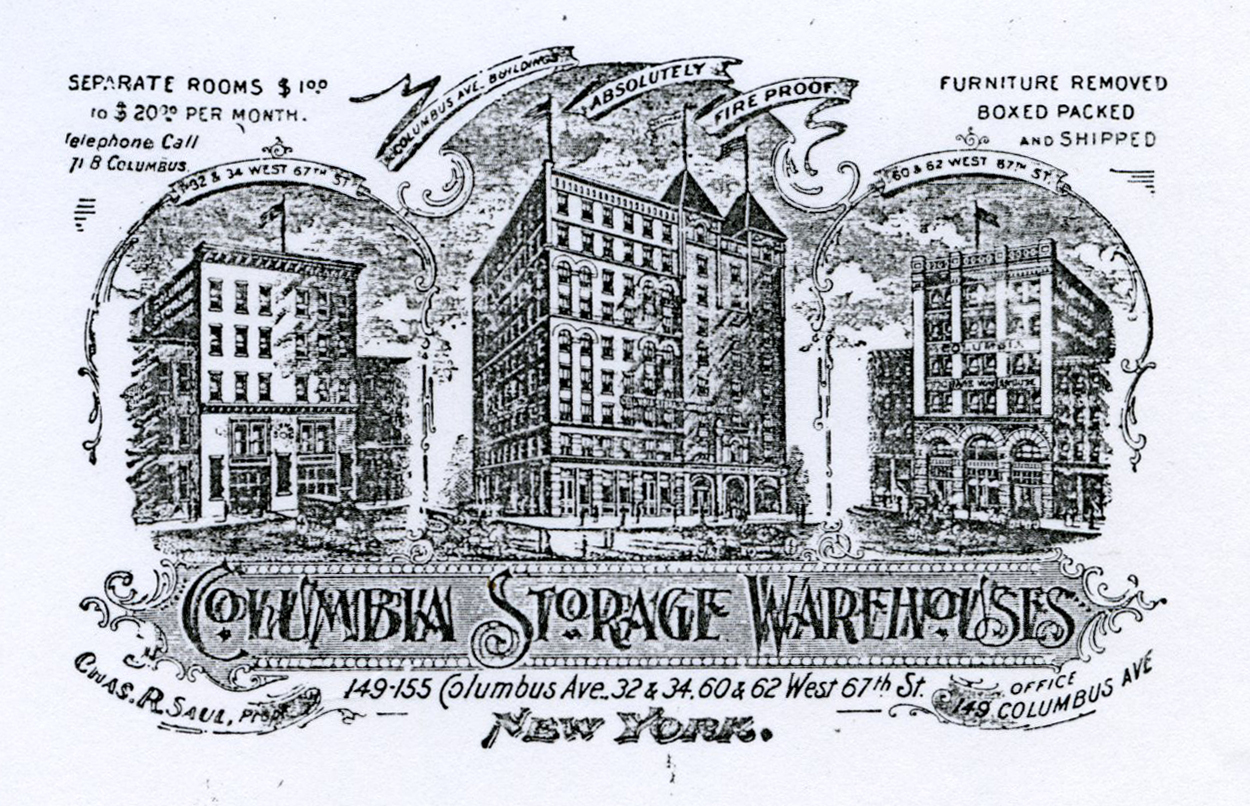

The Columbia Storage Warehouse buildings at 140-155 Columbus Avenue, 32 & 34 and 60 & 62 West 67th Street, once comprised one of the largest storage warehouses in New York City.[1] Their warehouses stored the furniture, clothes, toys, books, household items, and bric-a-brac of the rich and famous for decades. In their heyday in the 1900s and 1910s, the company and its leaders were in and out of the newspapers, for both good and bad reasons, but today, most would not recognize the name. No trace of this extended basement/attic for the rich and powerful remains today.

Columbia Storage Warehouses was founded by Charles Reuben Saul. Charles was born on August 18, 1855 to Jacob Saul and Mary Catherine (Barlet) Saul in Leesport, Pennsylvania. He received a public-school education and then attended a business college in Reading (PA). Upon graduation he immediately entered the business world, taking a job as a bookkeeper for J. L. Stichter & Son in Reading. Charles worked there for about eight years and then relocated to New York City, where he joined the produce commission business.[2]

Saul established himself in New York and then promptly started the Columbia Storage Warehouse in 1891.[3] In November of 1899 Saul purchased buildings at 149-151 Columbus Avenue, and 32-34 and 60-62 West 67th St. from Frederick de P. Foster for $430,000. According to the conveyance, at the time of purchase there was an 8-story brick building at 149-151 Columbus Avenue, a 5-story brick stable at 32-34 West 67th, and a 6-story brick building at 60-62 West 67th[4]. Saul also purchased the corner building at 153-155 Columbus Avenue sometime between 1892 and 1894. The structure was built in 1892 for Conrad Michaels, but Saul appears on the lease listing for this building in 1894 and 1898; no conveyance listing was found.[5]

The warehouses’ vice-president was David Edmund Dealy…he served in 1916 as part of the Mexican Expedition (or Pancho Villa Expedition) during the Mexican Revolution.

By 1895 Charles had established another business, the Clinton Storage Warehouses at 243 and 245 East 35th St[6] (incorporated on July 14, 1894[7]). In 1900 Charles had the business incorporated as the Columbia Storage Warehouses, with himself as president. By that point the company owned five storage warehouses, and had become one of the largest storage companies in New York City.[8]

Charles Saul passed away on January 28, 1948, at the age of 92. His wife, Alice Saul (nee Stroud), who he had married in 1878, had predeceased him in December 1933. They were both survived by their daughter, Lulu Mabel Saul, and her two daughters.[9]

The warehouses’ vice-president was David Edmund Dealy. Dealy was born July 8, 1864, in New Rochelle, New York. He enlisted in the Troop A Cavalry in April 1889. It is unclear when he began working for Columbia Storage Warehouses, but his New York Times obituary states that he served in 1916 as part of the Mexican Expedition (or Pancho Villa Expedition) during the Mexican Revolution.[10] Dealy married the daughter of European immigrants, Aimee Dealy, and had five children with her. The 1910 census reveals that the couple lived with their five children, aged 13-21, and a “mulatto” servant, Belle McCoy.[11]

Tragically, Aimee took her own life the following year. On June 5, 1911, the New York Tribune claimed that Aimee (or Anna, as they named her in the article) had “carefully planned her death” by closing all the windows and stuffing up all the cracks before seating herself “in a chair in the center of the room and directly beneath the chandelier, from every jet of which gas was pouring.”[12] David Edmund only survived his wife by about six years. He died of heart disease on April 18, 1917, at the age of 53.

Saul and Dealy led the Columbia Storage Warehouse company through many calamities during their tenures. Once one of the storage companies of choice for the rich and famous of New York City, the Columbia Storage Warehouse company earned further fame and infamy for at least two major (and expensive) fires and for its involvement in a particularly acrimonious high society divorce.

“BIG WAREHOUSE ABLAZE ” announced page 7 of the New York Times on July 10, 1900. Despite the many advertisements claiming that their buildings’ were fireproof, the three upper stories of the six-story annex building had burned, supposedly taking with it about “1,000 vanloads of furniture” and causing the injury of four firemen. The building had to be flooded to put out the blaze, and it was reportedly the water that had caused most of the damage to the furniture.[13] In January 1923 another fire, this time in an “airtight room,” caused about $10,000 worth of damage to the building, and destroyed about $100,000 worth of inventory.[14]

Fires were by no means uncommon, but the value of the goods stored in Columbia Storage’s warehouses made their potential destruction newsworthy. The company hosted several auctions on their property, all selling a large range of items, from china and crystal to furs and bric-a-brac. One auction advertised in the January 6, 1912 edition of the New York Herald, announced the sale of “handsome mahogany, oak and mission Dining Room Sets; Crystal Closets and China Closets; Parlor Suits, brass beds, bureaus, chiffoniers, hall seats, pier and mantel mirrors, portieres, books, silverware, brick-a-brack, etchings, mason Hamlin upright piano, oriental rugs, carpets & C.”[15]

Despite the many advertisements claiming that their buildings’ were fireproof, the three upper stories of the six-story annex building had burned, supposedly taking with it about “1,000 vanloads of furniture” and causing the injury of four firemen.

The warehouse company also earned its place in the New York City newspapers through its involvement in the rancorous divorce settlement of William C. Lesster, a wealthy old man with membership to the important Consolidated Exchange (the Consolidated Stock Exchange of New York, a direct competitor of the New York Stock Exchange from 1885 to 1926; located at the corner of Broadway and Exchange Place[16]), and Josephine E. Lesster. Josephine allegedly stored some goods at the Columbia Storage Warehouse which her ex-husband believed were his.[17] As the New York Times helpfully summarized “the storage company had refused to deliver the furniture to Mr. Lesster on the ground that his divorced wife…claimed all of it. While the defendant named in the suit is the storage company, Mrs. Lesster is the real defendant…Mr. Lesster wants the use of the furniture in dispute, and in reality is suing his first wife, a woman of middle age, on behalf of his second wife, who is 24 years old.”[18] The case was ultimately appealed up to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York, where a re-trial was ordered. It is unclear what ultimate ruling prevailed.[19]

Presumably the company was sold after Saul’s death, or, perhaps, run by his son-in-law. However, by 1944 Columbia Storage Warehouses was owned by James O’Neill, owner of Byrnes Brothers Warehouses, and the Lincoln Safe Deposit Company. According to an article in the July 16, 1944 edition of the New York Herald Tribune, O’Neill intended to merge the three companies.[20]

Today, the property once occupied by the Columbia Storage Warehouse company’s offices and warehouses has been broken up, with several different tenants across the former single property. For example, 149-155 Columbus Avenue had been occupied by a the American Broadcasting Company’s (ABC) television studio since 1978, until its sale on July 9, 2018 to Developer Silverstein Properties. You can read more about the effects of this sale, and the new structures being erected there here.

[1] “Classified Ad 4 — no Title.” New – York Tribune (1866-1899), Jan 30, 1897. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/classified-ad-4-no-title/docview/574250621/se-2?accountid=14512.

[2] Jordan, John Woolf. “SAUL, Charles R.” In Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania Biography Volume III. Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 2009. https://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/john-w-john-woolf-jordan/encyclopedia-of-pennsylvania-biography–illustrated-volume-3-dro/page-21-encyclopedia-of-pennsylvania-biography–illustrated-volume-3-dro.shtml.

[3] Jordan, John Woolf. “SAUL, Charles R.” In Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania Biography Volume III. Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 2009.

[4] Real Estate Record and Guide, November 4, 1899, pgs. 690 and 696;

[5] Real Estate Record and Guide, June 16, 1894, p.979; Real Estate Record and Guide, February 19, 1898, p.336

[6] “Classified Ad 4 — no Title.” New – York Tribune (1900-1910), Feb 24, 1906. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/classified-ad-4-no-title/docview/571797641/se-2?accountid=14512.

[7] “Lane’s Legal Tender Bill.” New York Times (1857-1922), Jul 14, 1894. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/lanes-legal-tender-bill/docview/95180277/se-2?accountid=14512.

[8] Jordan, John Woolf. “SAUL, Charles R.” In Encyclopedia of Pennsylvania Biography Volume III. Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 2009.

[9] “Charles R. Saul.” New York Times (1923-), Jan 29, 1948. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/charles-r-saul/docview/108123836/se-2?accountid=14512.

[10] “Obituary D. Edmund Dealy.” New York Tribune, April 21, 1917.

[11] Ancestry.com. 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Census Place: New Rochelle Ward 3, Westchester, New York; Roll: T624_1091; Page: 9A; Enumeration District: 0088; FHL microfilm: 1375104

[12] “Turns on Gas and Sits Down to Die: Mrs. D. Edmund Dealy, of New Rochelle, Had Carefully Planned Suicide Little Son Finds Body Woman Locks Windows, Stuffs Cracks, Turns On Jets and Calmly Awaits Unconsciousness.” New – York Tribune (1911-1922), Jun 05, 1911. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/turns-on-gas-sits-down-die/docview/574781061/se-2?accountid=14512.

[13] “Big Warehouse Ablaze: Fire Damages Seriously The Columbia Storage Building. A Thousand Van Loads of Furniture In The Burned Annex — Tottering Wall a Menace.” New York Times (1857-1922), Jul 10, 1900. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/big-warehouse-ablaze/docview/95998924/se-2?accountid=14512.

[14] “Gas Overcomes 14 Firemen in Airtight Room: 2 Giptains and 12 of their Men Caught in Trap Fighting Stubborn Fire in West Side Warehouse Revived with Pulmotors Blaze does $10,000 Damage to Building, $100,000 to Contents of Second Floor.” New – York Tribune (1923-1924), Jan 09, 1923. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/gas-overcomes-14-firemen-airtight-room/docview/1221608090/se-2?accountid=14512.

[15] The New York Herald. (New York, NY), Jan. 6 1912. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn83030313/1912-01-06/ed-1/.

[16] William O. Brown, Jr., J. Harold Mulherin, Marc D. Weidenmier, Competing with the New York Stock Exchange, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 123, Issue 4, November 2008, Pages 1679–1719

[17] Lesster vs Columbia Storage Warehouses , Casemine.com (Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York 1909).

[18] “Broker Sues For Furniture.: But Divorced Wife of W.C. Lesster Says It’s Hers, Telling Odd Story.” New York Times (1857-1922), Jun 20, 1907. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/broker-sues-furniture/docview/96771257/se-2?accountid=14512.

[19] Lesster vs Columbia Storage Warehouses , Casemine.com (Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of New York 1909).

[20] “Simons Resell Big Warehouse on 3d Avenue.” New York Herald Tribune (1926-1962), Jul 16, 1944. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/simons-resell-big-warehouse-on-3d-avenue/docview/1264402893/se-2?accountid=14512.

Katherine Taylor-Hasty is a PhD candidate at UCLA Berkeley

LEARN MORE ABOUT

149 Columbus Avenue

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 149 Columbus Avenue: