A “Ship that Never Goes to Sea” on Broadway Helped Build a Hospital in Greece

by Kelly Carroll, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

“The Colonial” building–as its name appears on a 1923 Bromley tax map–was an unusually short two-story building located on 66th Street at the nexus of Broadway and Columbus Avenue. The building was the gatekeeper of Lincoln Square and was steps from both the IRT subway and the El on Columbus Avenue. Perhaps its short stature was intentionally designed for the purpose of advertising at this strategic location on its roof. All historic photographs of the site display the demure building acting as a plinth for billboards as large as their host, of a scale that recalls Times Square.

The Colonial appears in the Real Estate Record and Guide in 1892 and was originally designed as a store and office building: “The first floor will contain 7 stores and the second about 24 offices.” The owner, Francis Crawford, hired architect Henry Andersen to design the 2-story brick and iron front building. Concurrently, Crawford also hired Andersen to develop nine townhouses on West 89th Street near Central Park West.[1]

Andersen, an immigrant from Norway, had just begun his career as a solo practitioner. He left the firm of Thom & Wilson in 1892, the same year he was hired to design The Colonial. No longer extant, The Colonial faced Lincoln Square with storefronts at the ground floor and featured punched openings spanning eight-bays at the second floor. This elevation was symmetrical, despite the building being on an irregularly shaped lot. Classical elements such as a Roman guilloche-studded entablature adorned the building on each side beneath its bracketed cornice. Squashed Corinthian pilasters flanked each of its corners. It appears to have originally been constructed in a buff Roman brick, with a darkly painted sheet metal cornice.

Perhaps its short stature was intentionally designed for the purpose of advertising at this strategic location on its roof. All historic photographs of the site display the demure building acting as a plinth for billboards as large as their host, of a scale that recalls Times Square.

Luckily for Henry Andersen, much of his prolific career is extant and enshrined in several New York City Historic Districts, including (but not limited to) the Upper West Side; the Riverside/West End Historic Districts and Extensions; Sugar Hill, Carnegie Hill, the Central Harlem 130-132nd Street Historic District, and even downtown in the Greenwich Village Historic District. As an independent architect, he did quite well for himself.

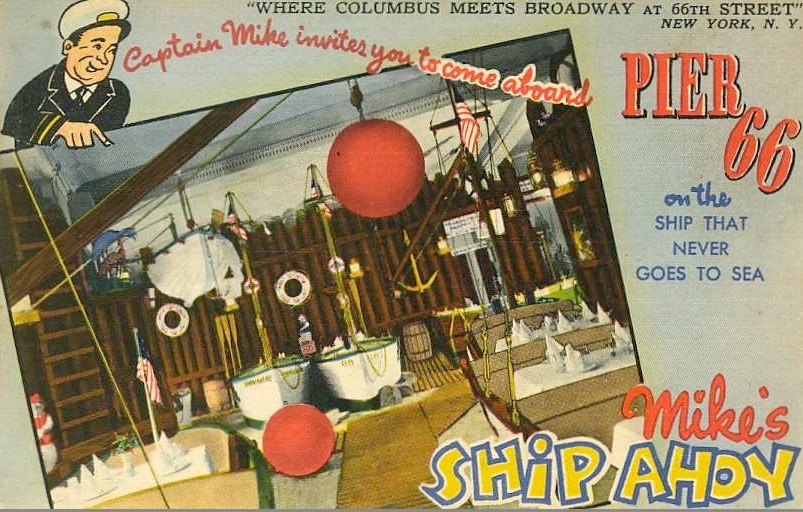

During this building’s lifetime, there is no other lessee that is a greater standout than Mike’s Ship Ahoy seafood restaurant. This restaurant, with its 88 foot long 66th Street frontage had the space to spell out its name in bold neon signage: Mike’s Ship A Hoy Sea Food Grotto. It is no doubt that its illumination at night was a tremendous contribution to The Great White Way’s radiance. “Ships Ahoy,” as it was known, was opened by a Greek immigrant named Mixalis Semitekolos. His name was Anglicized and/or Americanized to Michael Samet, and he was known to his customers as “Captain Mike.”

“Mike” immigrated to New York from the small Greek island of Kythera as a child, and like many Greek immigrants, went into the restaurant industry. Initially, Mike’s Ships Ahoy restaurant leased a portion of The Colonial in the early 1930s and expanded to occupy the entire floor plate of the building by the early 1940s. Business thrived during this time as evidenced by the restaurant’s promotional material, such as over-sized, free post cards paid for by the restaurant (“You address it—we mail it!”); its extensive menu; and its over-the-top interior décor.

The restaurant’s slogan of “Visit the Ship that Never Goes to Sea!” referenced a 104-foot-long yacht inside the eatery which served as the bar. Mike’s Ships Ahoy was more than a restaurant: it was a New York City destination. A promotional postcard from 1945 described the establishment as “An interestingly different nautical atmosphere. The only one of its kind in New York—showplace in the city of places to see! 104 foot yacht bar. 300 seating capacity. Colorful dining room! Upper deck. Promenade deck. Promenade bridge. Gangplank. Pilot room. Cabin nooks. Life boats. Marine effects. Main salon. For almost 12 years we have specialized exclusively in Fish, Lobster, and Plank Steak Dinners with the result that we are known everywhere.” By 1945 the restaurant additionally boasted a torpedo room called The Nautilus and had its own fleet of trucks.

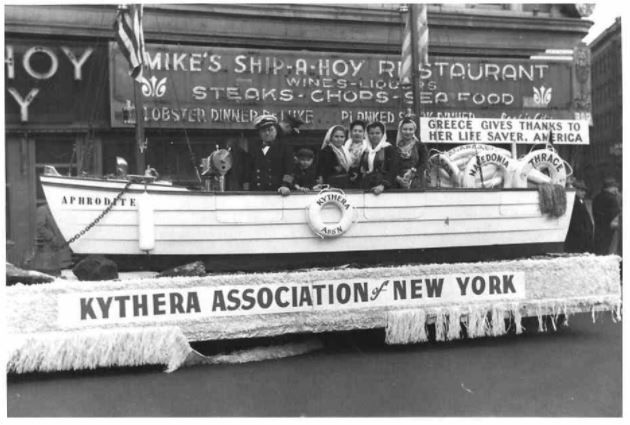

Mike cared deeply for his island home of Kythera, and his restaurant served the greater Kytherian diaspora in New York City. In addition to employing Kytherians as waiters, he was the president of the Kytherian Association of New York and hosted the organization’s meetings and celebrations at Ships Ahoy.[2] A photo from the 1940s shows a Kytherian Association celebratory float in front of the restaurant with a banner that reads: “Greece gives thanks to her life saver, America.”

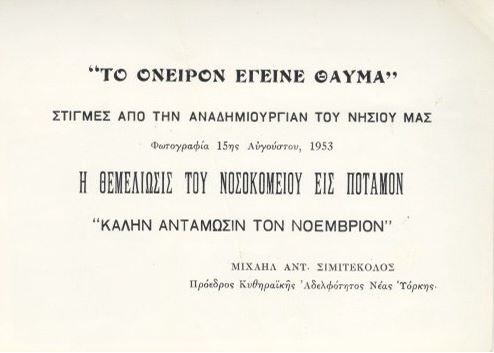

By the early 1950s, Mike was in a sound financial position which allowed him to give back to his modest island roots. He participated in a pan-Kytherian campaign to raise funds to construct the very first hospital on the island of Kythera, driving across the United States to solicit donations from fellow Kytherian-Americans.

For his work in raising money to build the hospital, Mike was recognized by King Paul of Greece with the Order of the Phoenix, an award that recognizes Greeks who have distinguished themselves in the fields of public administration, science, commerce, industry and shipping, and the arts and letters.

The fundraising initiative began in Greece by a man named Nikolaos Trifyllis from the Kytherian village of Trifyllianika. In Nikolaos’ last will and testament, he established a charity foundation entitled “Trifylleion Hospital of Kythera”, with the sole purpose of building and operating the first hospital on the island in Potamos, Kythera.[3] With the significant monetary aid of Mike, the hospital became a reality. The groundbreaking for the hospital was on May 21, 1953, and Mike attended. The charitable organization responsible for the hospital evolved to become the Trifylleion Foundation of Kytherians and is still active today.

For his work in raising money to build the hospital, Mike was recognized by King Paul of Greece with the Order of the Phoenix, an award that recognizes Greeks who have distinguished themselves in the fields of public administration, science, commerce, industry and shipping, and the arts and letters.[4]

While Mike’s Ships Ahoy was only in business for around 30 years in Manhattan, the contributions of Mike and the generosity of Greek-Americans made an indelible mark on the people of little Kythera, who previously never had a hospital. It remains the only hospital on the island to this day.

The 143-apartment, asymmetric 150 Columbus, developed by Millennium and designed by designed by Gary Edward Handel + Associates with Schuman, Lichtenstein, Claman & Efron as architect of record now occupies the block.

[1] “Out Among the Builders.” Real Estate Record and Guide 49 no. 1258 (April 23, 1892): 648-649.

[2] Notable Kytherians: Mixalis Anthony Semitekolos. Kytherian Society of California. Accessed: www.ksoca.com

[3] Trifylleion Foundation of Kytherians: About. Accessed: http://www.trifilio.gr/en/the-foundation

[4] Order of the Phoenix: the third Hellenic Order in the Hierarchy. Accessed: https://www.presidency.gr/en/hellenic-orders-decorations/order-of-the-phoenix/

Kelly Carroll is a historic preservation specialist and adjunct instructor at NYU SPS.

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 150 Columbus Avenue: