Stolen Cars, Arts and Hearts

by Tom Miller, for They Were Here, Landmark West’s Cultural Immigrant Initiative

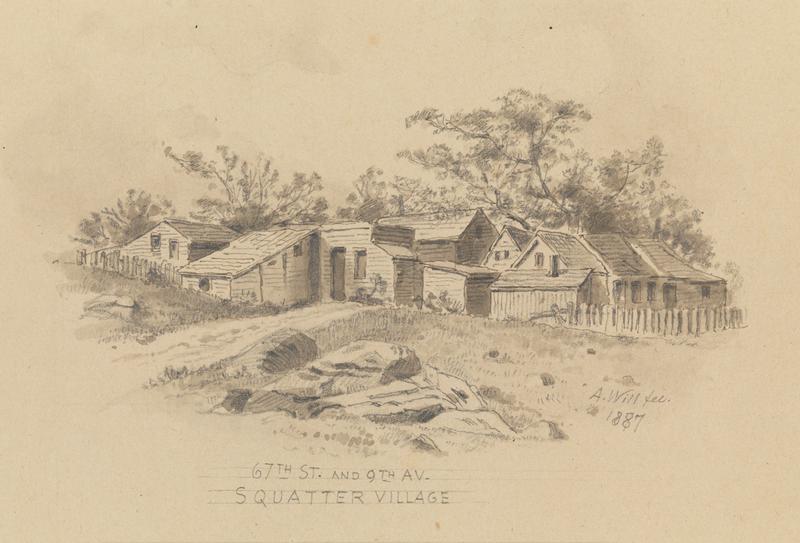

Developer and builder M. Giblin kept architect Max Hensel busy in 1887. In the eight month period between March and October alone that year Hensel filed plans for at least 11 structures for Giblin, mostly tenement buildings with stores. Among them was a structure at the southwest corner of Ninth (later Columbus) Avenue and 67th Street. Hensel’s plans, filed on September 16, called for a five-story tenement building with stores to cost $25,000 (in the neighborhood of $712,000 today).

Essentially forgotten today, the German-born architect was prolific at the time, specializing in tenement buildings. That would come to an end in 1892 when he was appointed a foreman in the Government’s Office of the Supervising Architect, overseeing Federal projects in New York.

No. 100 West 67th Street was completed in 1890. Hensel had saved his employer money on the crisp-lined building by executing most of the ornamentation in brick. Robust Greek key bands ran between the second and third floors, recessed panels were adorned with simple cross-hatches, complex geometrical designs, and other decorations. Chimney backs, which began at the third floor, were cunningly designed to match the fluted brick pilasters between the openings along the fourth floor. Above these, tympana were filled with honeycomb pattern brick. The pressed metal cornice repeated the Greek key pattern of the lower section.

Giblin sold the building to Louis Bauer, who leased the corner store to William A. Markgraf beginning January 1, 1900. Markgraf’s five-and-a-half-year lease began with a $1,800 per year rent, rising to $2,000. (He would be paying the equivalent of $5,000 per month today by the end of his lease.)

The apartments, all six-rooms each, were accessed by an impressive limestone entrance above a four-step stoop on 67th Street. The proportions of its arch mimicked those of the shop windows alongside, and it was embraced by fluted columns which morphed into overblown brackets. These, in turn, upheld an ambitious cornice. Pretty carved flowers filled the small spandrels of the arch.

Bauer’s advertisement in The Evening Post on April 16, 1892 offered:

HANDSOME CORNER FLATS,

One Block from L Station,

100 West 67th st.,

Six light rooms and bath-room, steam heat, in perfect order.

Rents $37.50, $42.50

The announced rents were annual; and so tenants in the most expensive apartments were paying just over $100 per month in today’s money.

Bauer held onto the property only until July 1895 when he sold it for $72,000.

Among the tenants in 1896 was Mamie Jane Atwood, also known as May. The New York Herald sarcastically described her on September 17 as being “known to herself as ‘Miss’ and to her friends as ‘Mrs.'” The article went on to say “Miss Atwood is a handsome, lavishly dressed woman. She is about thirty years old. She lives alone on the 5th floor of the house.”

Essentially forgotten today, the German-born architect was prolific at the time, specializing in tenement buildings. That would come to an end in 1892 when he was appointed a foreman in the Government’s Office of the Supervising Architect, overseeing Federal projects in New York.

She had been May Carmen, the widow of a dental surgeon, before her marriage to Frank J. Atwood. They had known each other only three months before the wedding and the groom soon regretted it. Three months into the marriage, Atwood was convinced his wife was unfaithful. He left her and went to Norfolk, Virginia. Mamie had him arrested there “for the theft of $1,600 in promissory notes.”

Later, when he found incriminating letters to her from a man who signed them only “H,” the pair had a “fierce quarrel,” according to The New York Times. Atwood “threw her out” and initiated divorce proceedings.

But The New York Herald‘s interest in Mamie had nothing to do with her messy domestic past; but with the fact that a wealthy, married man had been just been found dead in her apartment. Herman Feilman was “a fire adjuster and a man of wealth,” according to The New York Herald. He lived with his wife and daughter at 26 West 86th Street. The newspaper described him as being 50-years old and “a handsome man in the prime of life. He was well and tastefully dressed. He was one of those men who sought to keep young.”

Feilman shot himself in the head on the evening of September 16 in the Atwood apartment. Mamie’s version of things placed her away from the scene. She told authorities that she had just returned home from a walk with a Mrs. Lewis and the two were talking on the low stoop of 100 west 67th Street. Feilman came along and, although she “knew him only slightly,” he asked “permission to go up to her apartments last evening to rest, for he complained of being very ill and weary.”

Mamie said she gave him the key and remained on the stoop talking with Mrs. Lewis. Suddenly they heard the report of a gunshot and ran upstairs. Feilman’s coat and waistcoat were lying on a chair in the parlor and his body was on the bathroom floor. They immediately summoned police.

The Evening World found her story suspicious. “Feilman and the Atwood woman had known each other for a year or more,” said the article. (Frank J. Atwood agreed, telling authorities he was positive the love letters signed “H” were from Herman Feilman.) Moreover, it noted “There were many physicians’ offices in the neighborhood where he might have gone. And his own home was not far away.”

The Evening Telegram did not have to surmise. On the same day as the Herald‘s article, it ran a headline “Why Feilman Died.” The article said that two letters had been left by Feilman; one addressed to his wife and the other his employer, Leo Frank. Reporters who filed into Frank’s office were told that he would make the contents known after reading the letter, “but on reading it his face assumed a very serious look,” said The Evening Telegram. He now said “that out of consideration for Feilman’s family he could not tell the full contents of the letter.” The coroner was more forthcoming, saying that the letter indicated “that he killed himself on account of financial difficulties and his love for Mrs. Atwood…and was unable to support Mrs. Atwood any longer.”

Both Mamie and Mrs. Lewis were forced to change their stories when police informed them they had also found two photographs in his pocket–one of Mamie and the other of Mrs. Lewis (who had previously insisted she had never seen the man before). Mamie now admitted that she had known him “a year” (The World preferred to say she knew him “very well”) and that “he called on her occasionally.”

The World did some investigating and threw more light on Mamie Atwood. “The majority of her visitors were men. They were very quiet. There was never any disturbance.” Mamie took the first opportunity to bolt. “Police looked for her yesterday,” said The World, “but failed to find her. She left the flat without telling anyone she would be gone. Her only desire was to get away.”

James Ford, who lived here in 1898, was friends with Frank A. Keller. Keller worked for the Paris-based art dealers Goupil & Cie at 170 Fifth Avenue. Early that year it was noticed that paintings and etchings were disappearing and in March the police were called in. The New York Times reported “Their suspicion was directed to Keller, who for the past eight years has been the stenographer for the firm.”

Detectives got a break in the case when Keller and James Ford passed several worthless check on saloon keepers. When the proprietors confronted them, Ford and Keller offered valuable paintings to make good on the checks. At 1:30 in the morning on April 15, detectives broke into Ford’s apartment and arrested him.

Police said that Keller would use his key to get into the gallery at night. He and Ford would select artworks that they believed they could sell. The thieves had little-by-little spirited away $15,000 worth of paintings and etchings–nearly half a million in today’s dollars. Investigators found several of the paintings in Ford’s apartment. Other works were found in saloons, Keller’s apartment, and pawnshops.

Also living in the building that year was 18-year old Louise Betzer, who shared an apartment with Mrs. Charles Banks. The teen began visiting fortunetellers who told her the same story: that she would meet a handsome young man. Louise became preoccupied with the promise, repeatedly visiting the clairvoyants and astrologists. Later, according to The Newtown Register on September 29, Mrs. Banks said, “This seemed to occupy her mind more than anything else” and she frequently talked about her unknown lover. The Long Island City newspaper, The Eagle, on September 26 noted “The fortune tellers kept assuring her that she was to meet the young man soon, but finally she lost hope and talked of ending her life.”

On Saturday morning, September 17 Louise left No. 100. Later that afternoon, gravediggers in the Lutheran Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens, “came across the prostrate form of a pretty young women, lying on the grass in [the] rear of Lutheran Church, which is in the cemetery, with an empty bottle that had contained carbolic acid by her side.”

The Newtown Register reported “The girl was still alive when found, and the grave-diggers picked her up carefully and took her to the cemetery office.” Doctors felt she would recover “notwithstanding the fact that she swallowed three ounces of carbolic acid.” Louise regained consciousness the following day and confessed to police “that the reason she attempted her life, was that she was despondent.” The Eagle commented “Why she selected the entrance to Lutheran Cemetery as a place to end her life is not known.”

By 1908, the Reilly Restaurant was in the corner store. The proprietor seems to have struck a deal with the owner and doubled as a sort of in-house rental agent. An advertisement in The Evening Telegram on December 19, 1908 read, “Fine corner apartments, six rooms and bath, all improvements, to let…rent reasonable. Inquire in Reilly Restaurant, 100 West 67th, corner Columbus av.”

By now, Parkway Police, provided with a description of the Andrews vehicle, had joined the chase. It was spotted by Patrolman Van Cura who “brought McKeever’s short crime fling to an abrupt end.” The teen had managed to elevate his status from one of a non-punishable missing person to being held on grand larceny charges.

In the first years following World War I Wilma Gilmore ran her dance studio in the building. Her ads noted “Modern Dances, Stage and Society Jazz, specialized.”

The former Reilly Restaurant space had become the Buckingham restaurant by 1932. Problems came for the owner that year when U.S. Marshall Raymond J. Mulligan ordered a raid. An official announcement to the public in the New York Evening Post on March 29 read:

I have seized and hold One Cash Register, a quantity of Intoxicating liquor and a quantity of furniture and equipment found in premises known as Buckingham, designated as 100 West 67th Street, in the Borough of Manhattan…Notice is hereby given that the case is appointed for trial at the U.S. Court and Post Office Building, Manhattan, New York on April 12, 1932…All persons are notified then and there to appear and defense their interest…All not appearing will be defaulted.

We can most likely assume that no one came forward to claim the liquor.

The parents of teen-age John McKeever became concerned when he didn’t come home in October 1940. After receiving missing persons, a Mount Pleasant, New York police officer spotted McKeever and picked him up. The boy was being held at the police station awaiting the arrival of his parents. But he had other ideas.

The Yonkers newspaper The Herald Statesmen reported on October 22 that the teen “casually wandered away, stole Chief Joseph Klaus’ car and then led police on a chase.” With police vehicles not far behind, McKeever sped down the parkway before losing control and running the Chief’s car into the Woodlands’ viaduct in White Plains. “Leaving the car slightly the worse for wear, McKeever proceeded on foot into Scarsdale, where he stole an automobile owned by Joseph Lyon Andrews parked in front of his house.”

By now, Parkway Police, provided with a description of the Andrews vehicle, had joined the chase. It was spotted by Patrolman Van Cura who “brought McKeever’s short crime fling to an abrupt end.” The teen had managed to elevate his status from one of a non-punishable missing person to being held on grand larceny charges.

In 1983 the new Applause Cinema Books, a bookstore devoted to the theater opened here. That year journalist Lisa Faye Kaplan wrote, “The script for just about every play ever produced in modern times is for sale at Applause…The store, on Manhattan’s West Side, has a complete selection of Samuel French scripts, and one of the largest stocks of English plays in the country.”

But it was more than that. Writing in New York Magazine on October 19, 1987 Joanna Molloy called it “the city’s largest film bookstore” and added, “If this were just a bookstore, it would be interesting. Because it is also a scriptstore it is positively fascinating.”

For years, beginning around 1997, Nick & Toni’s Cafe was a familiar eating spot for Upper West Siders. While the Columbus Avenue store level has been totally modernized into a Starbucks, and later Sage Natural Wellness, the upper floors are intact; Max Hensel’s complex, eye-catching elements giving no hint of the colorful history that played out inside.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

LEARN MORE ABOUT

100 West 67th Street

Keep

Exploring

Be a part of history!

Shop local to support the business currently at 156-158 Columbus Avenue/100 West 67th Street:

Meet Alizee Wyckmans!