Verdi Square

by Tom Miller

By the turn of the century, when Charles Barsotti initiated the idea of a monument to Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi, the neighborhood of Broadway and 72nd Street had developed into one of handsome apartment buildings and residences. Barsotti was an aggressive promoter of things Italian. The founder and editor of the Italian language newspaper Il Progresso Italio-Americano, he had already spearheaded the erection of the 1888 statue to Giuseppe Garibaldi in Washington Square and the 1892 Christopher Columbus monument in Columbus Circle.

Now he turned his attention to the composer whose name had become nearly synonymous with Italian opera. As he had before, Barsotti used his newspaper to solicit donations for the project. The New-York Tribune, on March 3, 1901, used decidedly prejudiced rhetoric to express its doubts that the working class Italians would chip in.

“Naturally, there is a distinct line of separation between the opera gallery classes of Italians and those of the race who seldom or never go…It is only the more intelligent workmen—shoemakers, tailors, silversmiths and such—who spend their money for opera; the ‘scafoni’ (bumpkins), who come over to labor with sheer muscle, bring utterly untutored minds in which the Italic racial instinct for song is dormant. Before he left his Calabrian hamlet, the scafone never heard anything more musical than a cheap cowbell…It will be interesting in connection with this view of the Italian New-York proletariat to watch the progress of the movement said to have been started by an Italian journal of this city to erect a monument to Verdi.”

Despite the newspaper’s doubts; the fundraising pushed on. When the new Italian steamship Sicilia berthed at the foot of West 34th Street two years later, wealthy Italian New Yorkers were shown around as part of the effort. The New York Times said the event was “to further the idea of Charles Barsotti, editor of the Italian newspaper Il Progresso, to erect a statue to the composer in this city. A fund of $12,000 is to be raised among the Italians of the city to meet the expense.”

At the time of the on-ship dinner, $4,000 had already been raised and the model of the monument was completed. Artist Pasquale Civiletti of Palermo had been given the commission. Civiletti’s four-foot high model had traveled to New York with the Sicilia and sat at the head of the speakers’ table.

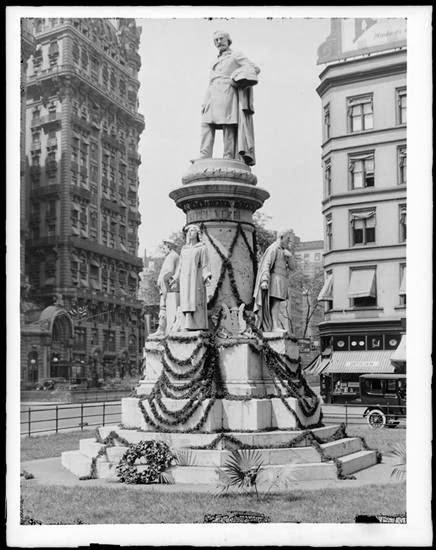

The New York Times said “The model has been highly praised by Italian critics such as Guilio Monteverde and Ernesto Biondi” and briefly described the work-in-progress. “The monument, when finished, will be about the size of that of Christopher Columbus at Fifty-ninth Street and Eighth Avenue. It will be of Carrara marble, on a granite pedestal.” The newspaper said “About the pedestal are four figures representing the leading characters in the operas ‘Aida,’ ‘Falstaff,’ ‘Otello,’ and ‘Fonza del Stino.’”

The New-York Tribune, on March 3, 1901, used decidedly prejudiced rhetoric to express its doubts that the working class Italians would chip in.

Three years later, on August 24, 1906, the steamship Sannio pulled into port with the completed monument on board. “Chevalier P. Civiletti, the sculptor who made the monument, was also on board the vessel,” reported The Evening World. The ship transported the monument free of charge.

The New-York Tribune which had been skeptical in 1901 about the ability of the Italian community to raise $12,000 for the monument, would now have to eat its words. Four days after the Sannio docked the newspaper reported “The sum of $20,000 was raised by the Italian newspaper, ‘Il Progresso Italio-Americano,’ for the monument.”

On September 20 the cornerstone was laid during a rainstorm that did not dampen the elaborate fanfare. Fifty Italian societies from New York and nearby cities formed a parade to Broadway and 73rd Street led by Frank de Caro as marshal. Italian Consul General Count A. Raybaudi Massiglia served as master of ceremonies before a throng of nearly 10,000 men, women and children.

“A pleasant feature at the laying of the cornerstone was the singing of ‘America’ by three hundred school children to a tune composed by Signor Giacomo Quintano, who hopes to have this country adopt it,” reported the New-York Tribune.

The Italian-American community’s enthusiasm and satisfaction was tarnished only by anti-Italian harassment. On August 27, 1906 Barsotti hosted a dinner for the sculptor on the pier of the Italian Line on the Hudson River at 34th Street. Esteemed Italian-Americans spoke. “Remarks were made in praise of the sculptor and the enterprise,” said the Tribune, and “Civiletti expressed his gratitude for the demonstration in his honor.”

Then, “the policemen on the beat dropped in to see what was the trouble.”

The incident was merely an annoyance compared to the benefit production of “Il Travatore” scheduled for September 30. Nearly 15,000 opera-goers bought tickets in support of the monument fund. When they arrived at the Academy of Music, police were there to turn them away.

Notices were posted in Italian explaining that no performances, by law, could be staged on a Sunday. The New-York Tribune noted, however, that “The Dewey, which is a Sullivan theatre, was not interfered with, and other theatres had their usual concerts.” It added “It was hinted that the police, under orders from the Commissioner, might have stopped the benefit for political reasons.”

The performers pointed out that if they went on with the opera without costumes, they could get around the law. The newspaper reported “but the police declared that if they had been allowed to go on without costumes there would have been trouble. They say the Italians would not stand such a performance.”

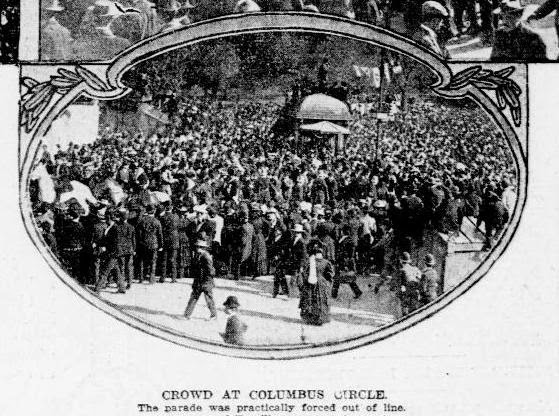

Despite such problems, the unveiling of the Verdi monument took plate on October 12, 1906, the 414th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in America. The spectacular ceremony was worthy of a scene from one of Verdi’s most lavish productions. Five thousand marchers from various Italian societies assembled at the Washington Square arch at 12:30 and processed up Fifth Avenue led by “the Verdi body guard.” The parade stopped at Columbus Circle to lay wreaths at the base of the Columbus statue, then proceeded to 73rd and Broadway.

The New-York Tribune noted “One of the most picturesque bodies in the parade was the Italian Veterans, men who had seen service in the Italian army, many of whom bore scars of wounds caused by Abyssinian spears. These men carried a tattered banner, which evoked cheers from the thousands who gathered at the square.”

Ten thousand people were waiting, along with the Metropolitan Opera House orchestra and a chorus of 150 voices. Following music and speeches, the unveiling was as dramatic and choreographed as ever was seen on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera.

Charles Basotti’s little granddaughter, Gertrude Amelia Garhmann, pulled a string which released a large balloon anchored near the monument. “The balloon shot up into the air and carried with it the veiling of red, white, and green which concealed the statue,” wrote The New York Times the following day. “As the balloon soared upward, twelve doves were released from the folds of the covering and flew high over the heads of the spectators.”

Civiletti’s monument was as impressive as its unveiling.

As if this were not spectacle enough, there was more. “A shower of roses and other flowers representing the Italian colors also fell from within the balloon as it rose in the air.”

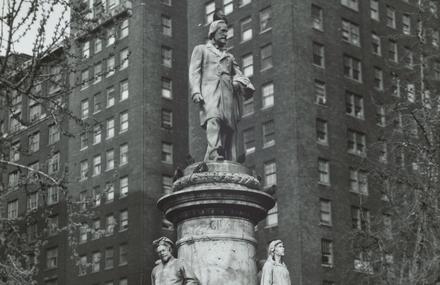

Civiletti’s monument was as impressive as its unveiling. The 15-foot tall Carrara marble statue of the composer stood on a dark granite pedestal, around which were the four life-size marble sculptures of operatic characters. The dramatic figures added to the fitting monument to the composer.

The Sun called the unveiling “a tribute most fitting.” The newspaper concluded “One of the loftiest figures in music, Verdi was also distinguished as a patriot, a philanthropist, and a man of pure and simple life. Americans will be glad that the composer’s countrymen have set up in New York a lasting memorial of this illustrious tone poet.”

The little triangular park was renamed Verdi Square in 1921. Unfortunately, the Verdi monument would suffer neglect before long. On May 13, 1931 syndicated columnist O. O. McIntyre lamented at the condition of New York’s monuments. “Even the Statue of Liberty is in constant need of brightening. It is inspiring only as a symbol. The statue in Greeley Square is square and awkward. Few ever notice it. That is true of Verdi’s statue at Broadway and 72nd st.”

By the 1960s Verdi Square was overgrown and neglected. Residents skirted the adjacent area–littered with drug dealers, addicts and the homeless–that had earned the nickname “Needle Park” and was the setting of the dark 1971 motion picture “The Panic in Needle Park” starring Al Pacino.

Despite its degraded condition, Verdi Square was designed a Scenic Landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1974. In doing so the Commission noted that “Verdi Square is scheduled for renovation in the near future.” The “near future” came in 2004 when the Metropolitan Transit Authority opened a new subway station nearby and the Parks Department reconstructed the Square.

In the meantime, the Verdi monument was restored in 1997 with money provided by the Broadway/72nd Associates. Four years later it was once again grime-covered and frustrated singers from the New York Grand Opera Company took matters in their own hands. Vincent La Selva told New York Post reporter Barbara Hoffman, “It looked terrible. We wheeled a piano out on the sidewalk, sang some arias—then got ladders and buckets and cleaned it off.”

The maintenance of the Verdi statue is now guaranteed by a permanently endowed fund by Bertolli USA, Inc. The landscaping of the square is provided by an endowment by classical music announcer Harry Fleetwood of WBAI radio station in memory of his brother James H. Fleetwood.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business in Verdi Square: