The Beacon Theatre Interior

by Megan Fitzpatrick

The opening of the Paramount Theater in 1926 in Times Square was a significant event that propelled the construction of movie palaces to new heights. The same year, plans got underway to build yet another movie palace, this time on the Upper West Side. The Beacon Theatre at 2124 Broadway was one of the last of the great New York City movie palaces built before the onset of the Great Depression. During the 1920s, movie theaters captivated audiences by integrating vaudeville and live music into their programs to accompany silent films. By the late ’20s, theaters were designed with talking pictures in mind. The Beacon Theatre in New York City was built during this transitional period, and its design is a rare amalgamation of silent and talking picture technology.

The popularity and endurance of movie palaces came down to their accessibility, from the early crude nickelodeons, which the children of the tenements would flock to, to lavish movie theaters that sprung up in Times Square and beyond. As Stern, Gilmartin, and Mellins wrote in New York 1930:

“The movie palace offered far more than celluloid romance to the community it entertains and sometimes educates. Its patrons may absorb their ideas of dress, of deportment and of love-making from the slim-hipped heroines who glide across the screen, but their knowledge of such art as is represented by the symphonic orchestra, by architecture, by sculpture, and by interior decoration is frequently acquired from the theatre itself. A decade ago only the wealthiest and most fortunate could hear such music or move at ease amid such luxurious, and often artistic, surroundings as are offered today along with entertainment to any patron of the newest million-dollar movie palaces, at an average admission charge of fifty cents.”

The grandness and richness of the key interior spaces – the grand foyer, the intimate lobbies and the soaring auditorium – helped reinforce that feeling of being transported to exciting places.

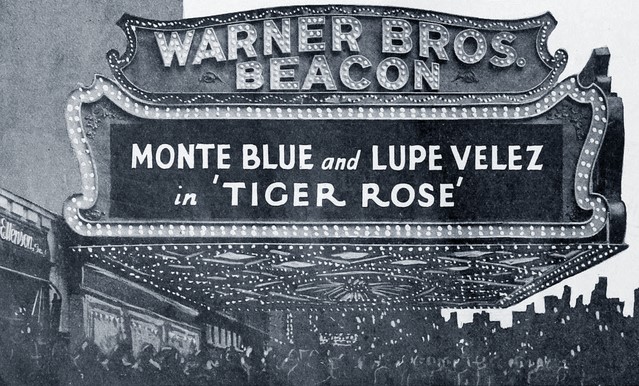

Film producer Herbert Lubin envisioned a chain of sumptuous movie palaces in New York and recruited Samuel L. “Roxy” Rothafel, successful theater promoter, to make his vision a reality. The innovative, and not-so-humble Roxy would build The Roxy, a 6,000-seat flagship theater for his chain known as the Roxy Theater Circuit. Up-and-coming Chicago-based architect Walter W. Ahlschager designed. The two would collaborate again on a smaller sister theater called the Roxy Midway Theatre, which would later be known as The Beacon Theatre. The Beacon was half the size of the Roxy, but its developers had placed all their bets to ensure its success. Unfortunately, after a series of financial setbacks, Lubin and Roxy both pulled out of the project, and construction plans halted in 1928. The following year, the sale of the theater to Warner Brothers, the leading film company in the country paving the way for the advancement of “talkies,” revived development plans. Warner Bros. hired the architecture firm Rapp and Rapp to make final alterations before opening and critical renovations to make it compatible for sound.

…skip the exterior. It’s the opulent interior, second only to that of Radio City Music Hall, that counts.

The interior was designed to delight the audience and create an exciting theatrical experience, even before any performance took place. On opening night, Christmas Eve, 1929, when Harry Warner made a welcome speech, and the feature film was “Tiger Rose,” one attendee observed that the auditorium was “a true bit of Bagdad (sic) on upper Broadway.” Another said it gave “the feeling of being in some impossibly vast tent of some fabulous oriental potentate.” Its designers leaned into a broad Eastern influence to dazzle a Western audience. The ostentatious design was very on-trend for the period and for this building type. It wasn’t everyone’s favorite, of course, there are always critics.

The writer and cultural critic H. L. M. Mencken once commented on the growing popularity of movie theater construction, stating, “I advocate hanging architects whose work is intolerably bad. Most of them specialize in the design of movie and gasoline cathedrals.” The AIA Guide, however, celebrated its lavish interior, writing, “skip the exterior. It’s the opulent interior, second only to that of Radio City Music Hall, that counts.”

The eclectic opulence of the interior was emphasized by its mix of styles, which drew inspiration from Greek, Roman, Renaissance and Rococo architecture. These styles are represented most by the eight-story high auditorium, which included Persian frescoes, Egyptian sphinxes, Roman shields and helmets, gigantic urns, Venetian light fixtures, Byzantine and Aztec flourishes, monumental gilded statues and a chandelier so big that a man can stand upright inside to change a lightbulb.

Many elements of the Beacon’s design are often said to be based on original designs for the now-demolished Roxy Theatre. Although the Beacon is smaller in scale, technical innovations such as a revolving stage and movable orchestra were incorporated, as well as the dramatic space of the rotunda lobby. The entrance to the rotunda is richly decorated, framed by large marble pilasters, a swag-adorned frieze that encircles the rotunda, and an ornate ceiling. Above the entrance doors is a mural painted by Danish artist Valdemar Kjelgaard.

The Beacon remained a movie theater until the mid-1970s, although its splendor faded during the decades following the Depression, a number of renovations aimed to revive it, including when Steven Singer bought the venue in 1974. Stephen Metz was subsequently hired to promote several pop concerts to be held at the theater. Two years later, the theater was purchased by Allen Rossoff and Marvin Getlan. Its primary focus would soon change from movies to live music.

In 1979, the theater interior was designated a landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and in 1982 was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Then, in 1986, new owners announced plans to transform the Beacon into a cavernous disco with a three-tiered restaurant. Despite opposition from the general community and despite the efforts of grassroots organizations such as the Committee to Save the Beacon Theatre, permission was granted by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. The conversion plan would have involved the removal of many of the interior details and the installation of a dance floor in the orchestra seats and a kitchen and restaurant on the balcony.

Plans were halted by a Supreme Court Judge almost a year later who ruled that the project would cause irreparable damage to the protected interior, and the alteration never came to fruition. “Conversion to a discotheque will not safeguard or enhance the city’s historic aesthetic and cultural heritage,” wrote Judge Jacqueline W. Silbermann.

The conversion plan would have involved the removal of many of the interior details

In 2006, Madison Square Garden Entertainment, a division of Cablevision Systems Corporation, entered into a 20-year lease of the theater. Beginning in September 2008, the Beacon underwent a six-month, $16-million restoration of the interior under the direction of Beyer Blinder Belle Architects, which sought to preserve the changes made to the interior over time. “We felt it mandatory to preserve the development and change in use of the theater over time, which essentially began with the first renovation in 1929,” said Christopher Cowan, associate partner at the firm during the renovation.

Time had not been kind to the interior landmark, with almost all the decorative paintings and gilded finishes painted over, including Kjeldgaard’s mural. The auditorium seats had been replaced many times, and damage from water leaks and inadequate maintenance affected the balcony, main theater ceilings, and much of the paint and plasterwork. The architects at Beyer Blinder Belle used drawings and black and white photographs to document and restore the work of Altschlager and Rapp & Rapp, but admit, in many cases, they could not determine for sure whether uncovered layers in the restoration process dated from 1927 or 1929. The firm also worked with EverGreene Architectural Arts to uncover remnants of the original finishes hidden behind up to 10 layers of non-original paint.

The restoration was completed in six months, and the Beacon reopened in February 2009, celebrated with a Paul Simon concert. Bob Dylan, Roger Waters, Tom Petty, and George Carlin are a few of the renowned artists who have performed at the Beacon Theatre over the years. The Allman Brothers played their first of 238 concerts at the venue in 1989. The group played at the theater for three consecutive weeks in 2009 to celebrate their 40th anniversary. Their show at the Beacon Theatre on October 28, 2014, was the Allman Brothers’ final live concert.

Today, the Beacon remains a fixture in the cultural and artistic heritage of the Upper West Side.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Director of Research and Preservation at LANDMARK WEST!