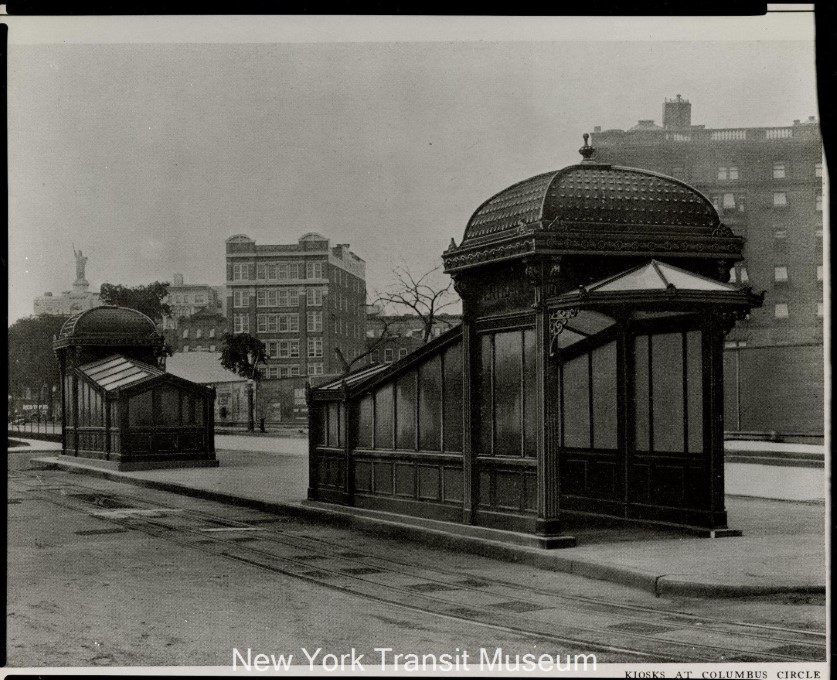

View of 59th Street and Columbus Circle station. Image Courtesy of New York Transit Musuem Subway Construction Photograph Collection.

The Interborough Rapid Transit Subway System Interiors

by Megan Fitzpatrick

Traffic congestion in the mid-nineteenth century caused by the rapidly developing city prompted discussions of an underground rapid transit system. The Rapid Transit Commission was formed in 1891 to explore the possibility and a contract was signed eight years later for the creation of the first subway line in the city that would be known as the Interborough Rapid Transit system (IRT). The Rapid Transit Subway Construction Company was formed and charged with its development and received the backing of wealthy financier August Belmont Jr. The first line under this contract began with a loop under City Hall Park, then went north towards Times Square (then, still-called Longacre Square) and turned along Broadway northward to 96th Street. It then branched into two lines leading into the Bronx.

During this time, the Upper West Side was undeveloped compared to the density that exists today. Huge swaths of farmland remained, but speculative developers would capitalize on the Upper West Side’s new connection with the rest of the city. The new underground system was also a welcome addition to the neighborhood as the existing mode of public transportation, the Ninth Avenue El, or elevated train line, created a shadowy corridor along Columbus Avenue that had already begun to get a bad reputation among residents.

Construction began on the new line in March 1900. The route named the “West Side Line,” also known as the IRT Seventh Avenue Line, was devised by Chief Engineer William Barclay Parsons. Parsons studied European transit systems and tried to apply what he learned to the New York City subway system, including the importance of aesthetics and wall treatments. Parsons’ system consisted of local and express tracks, distinct in terms of platform layout, but ultimately unified by their construction, including station walls that are four-inch thick and made of brick and cast-iron columns placed at 15-foot intervals that carry the station roofs.

…the 1899 IRT contract specified the use of white or light-colored tiles to brighten the subterranean stations.

While Parsons was in charge of the route and construction, the architects oversaw the “artistic treatment and decoration of the stations,” subject to Parsons’ final approval. Many top firms of the period were considered, including Carrère & Hastings, but in 1901, Heins & LaFarge were selected. George L. Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge studied together at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology under the supervision of French-born Eugene Letang and established their firm in New York in 1886. Not long after that, they rose to prominence by winning the design competition for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and served as architects for the first phase of construction. They were then chosen to take on other large projects of the late nineteenth-century, including Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church and the New York Zoological Gardens in the Bronx.

It’s no surprise they were entrusted to design the interiors of the new subway system and their related control houses and kiosks. Once again, they were faced with a challenge, the same one they faced with the Cathedral and Zoological Gardens commissions–devising an architecture for which there was no obvious prototype in the city. However, they had a guideline. The 1891 Report of the Rapid Transit Commission outlined that every effort should be made “in the way of painting and decoration to give brightness and cheerfulness to the general effect” of each of the stations. Additionally, the 1899 IRT contract specified the use of white or light-colored tiles to brighten the subterranean stations. The glossy ceramic three-by-six-inch “subway tile” that we know today was originally designed by Heins & LaFarge and placed in the city’s first subway stations. This clean and bright wall treatment then met two-and-a-half-foot wainscoting of buff Roman brick or rose-colored marble and a myriad of motifs framed in plaques or swag surrounds.

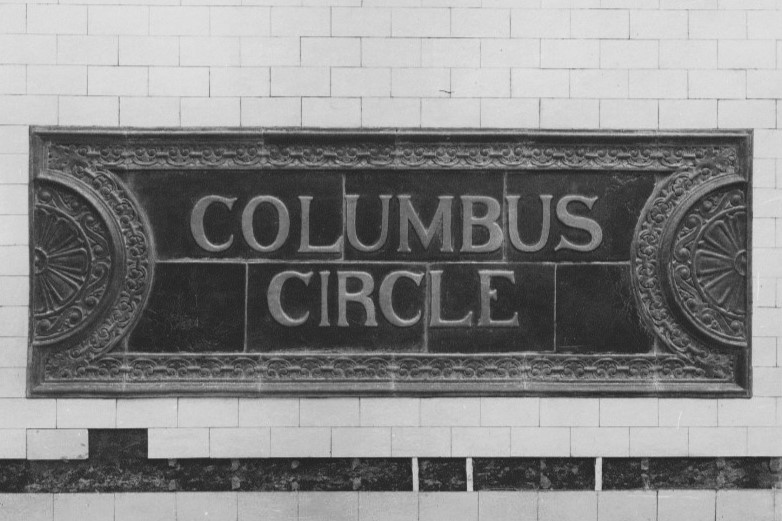

The architects composed a decorative plan that connected the new station interiors yet gave each a distinctive identity through color and ornamental detail. Heins & LaFarge often incorporated symbols or motifs that have some local association with the station, for example, the “Santa Maria” depictions at 59th Street and Columbus Circle Station. Christopher Columbus’ sailing ship, the Santa Maria, symbolically ties the station to its namesake, is displayed within blue, green, and cream faience plaques elegantly crafted and set above a green faience swag and enframed by a rope motif and flowers.

The 72nd Street Station has a distinctive identity, not only for its iconic control house or kiosk, designed by Heins & LaFarge, but also for its island platform layout and wall treatment. Parsons, Heins, and LaFarge intended to differentiate the express stations from the local stations, and they achieved this through design. 72nd Street, an express station, was designed without name tablets on the walls of the station, and instead, signs on the island platform were intended to state the location. The walls, however, were not bare and designed with panels of florals, rope, and fretwork motifs in shades of blue, buff, and cream.

The 79th Street and 110th Street stations are both local tracks and share striking and colorful wall treatments in buff and green mosaic tile. At 79th Street, buff and green mosaic tile pilasters pierce the wall at intervals with the “79” displayed near the center. At the 110th Street Station, the most striking aspects are the large name tablets with the inscription “Cathedral Parkway.” White letters are set in a green mosaic tile enframed by floral, foliate, and geometric motifs in shades of buff, pink, and red.

Heins & LaFarge often incorporated symbols or motifs that have some local association with the stations

The West Side Line opened in 1904 to rave reviews. The stations, particularly their interior, were described as a “delight to the eye,” succeeding in brightening these below-ground train stations. The preserved portions of these four Upper West Side stations from 1904 highlight the elegant mastery of Heins & LaFarge and gained them the distinct honor of being among the few interior landmarks recognized by the City.

When they were first unveiled to the public, the City was congratulated for its commendable contribution to civic art. This can also be said of today as public art continues to be commissioned within Upper West Side stations. At 59th Street, a display of a variety of subway tiles hangs prominently on the station walls. These were installed as prototypical samples in the early days of construction when Heins & LaFarge experimented with different materials. They were then covered up, only to be revealed in 2007 during renovations. At 72nd Street, above the station house, is Laced Canopy made up of over a million hand-cut pieces of glass laminated to the inside of the skylight. This work was commissioned by the MTA and designed by Robert Hickman.

Megan Fitzpatrick is the Director of Research and Preservation at LANDMARK WEST!