The Sherman Square Station

by Tom Miller

When the idea of a subway line in New York City was first bandied about in 1864, the Upper West Side was mostly undeveloped, rocky terrain. It was not until February 1900 that the Rapid Transit Construction Company signed a contract with the Rapid Transit Commission that would result in construction of the subway that would stretch into the Upper West Side.

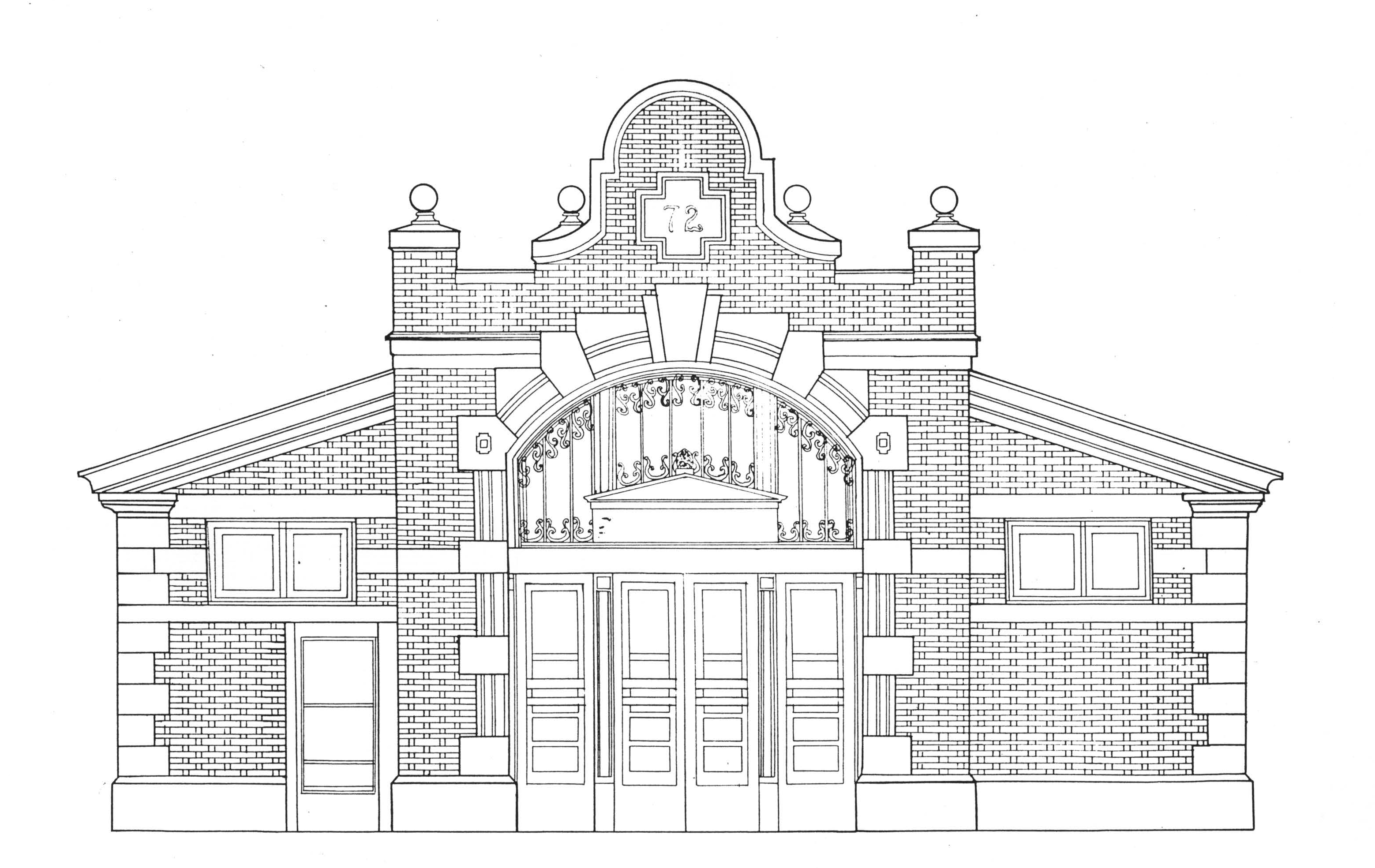

The West Side Line, from 60th to 82nd Street, was begun on August 22, 1900. A year later, the Rapid Transit Construction Company hired the architectural firm of Heins & LaFarge to design the underground stations as well as the control houses—or kiosks–at street level. (They were called control houses because they were meant to control the flow of passengers to the underground platforms.) George Lewis Heins (the son-in-law of eminent artist John LaFarge) and Christopher Grant LaFarge (the son John LaFarge) had worked under Henry Hobson Richardson and opened their own office in 1886.

For the 72nd Street control house, the firm nearly copied the one at the Bowling Green station—a Flemish Renaissance style structure faced in beige brick, trimmed in stone, and accented with colorful terra cotta. Below ground—again in both stations—they designed intricate Pompeian style mosaic wall panels above the tracks. The ceramic tiles were manufactured by Grueby Faience Company of Boston.

Sitting within a triangular traffic island and originally called the Sherman Square Station, it opened on October 27, 1904. The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide praised the stations in general, saying “New York can congratulate itself on one specimen of ‘Civic Art,’ in which a very useful structure has been decorated with the utmost propriety.” The residents of the Upper West Side, on the other hand, were less appreciative.

On September 11, 1904, The New York Times called the kiosk “a barnlike structure,” and said, “Ornamenting the centre [sic] of beautiful Sherman Square with such an architectural freak has not brought down the blessings of the neighborhood upon the Rapid Transit Commission, the engineers, the designers, and the contractors.” A member of the exclusive Colonial Club told the reporter it “looks like a mud fence.”

“A foreigner who was being taken to the Colonial Club a few days ago by a member, it is related, stopped still at the sight of the obstruction, carefully fixed his monocle and remarked, ‘Public comfort station, I presume?’”

“There are doorways in the front and rear walls which…are topped by what might be termed ornamental curves by anyone with too little taste to appreciate the hideousness of the deformity as a whole,” said the journalist. He seemed to have gotten glee in repeating a comment heard earlier in the week. “A foreigner who was being taken to the Colonial Club a few days ago by a member, it is related, stopped still at the sight of the obstruction, carefully fixed his monocle and remarked, ‘Public comfort station, I presume?’”

The article noted, “The residents have made no formal complaints to the city authorities, so far as anyone in the neighborhood could say yesterday.” But that would soon change. The West Side Association, a powerful lobbying group for the Upper West Side, soon demanded that the kiosk be demolished and replaced by a “more sightly” one. That would not happen.

West Siders seemed to grow accustomed to their station and so, on the morning of June 9, 1914, it was not aesthetics that occupied the minds of passengers, but the fear-inducing behavior of James Munroe. A plasterer, he rushed into the crowded station shouting that “enemies” were trying to kill him. He pulled a saw from his bag of tools and shouted that he “would defend himself while life lasted.”

The Evening World recounted, “Men and women in the station fled past the ticket choppers to the platforms below.” When Policeman Ludenmann drew his nightstick, the man rushed forward and pleaded for protection. “They’ll kill me!” he shouted. Lundenmann channeled his inner psychologist and promised to protect Munroe. He then called Dr. Boyd at the Polyclinic Hospital who arrived with an ambulance to take him away. The diagnosis was swift. “The surgeon said Munroe was crazy and took him to Bellevue Hospital.”

The firm of Ward & Gow had the contract for the subway advertising, and its management was firmly against the Suffragist Movement. The subways were plastered with political notices explaining the negatives of giving women the right to vote. The firm flatly refused to allow the Suffragists equal space.

Unable to get their own posters exhibited on subway cars, the stalwart ladies took matters into their own hands. Calling them “lapboard ladies,” The Sun reported, “They gathered, a score of them, at the Seventy-second street station at 2 o’clock in the afternoon, each carrying a neat little card with printed arguments answering the statements with which Ward & Gow, advertisers, have allowed the anti-suffragists to adorn every subway car.”

Led by Mrs. Norman de R. Whitehouse, the “brigade of living advertisements” dropped their tickets into the box. Half took the express train, and the others took the local. They women then took seats as near the anti-Suffragist propaganda as possible, holding their placards in their laps for everyone to see. The cards had been carefully designed to counter each of the claims of the anti-Suffragist posters. A point, for instance, read, “Don’t be fooled. We have the word of the Secretary of State in each of the twelve States where women vote that taxation has not increased.”

The campaign seems to have worked, at least for some. When one woman was asked by two workmen why they were doing this, she explained that they had been unable “to buy the right to place their advertisements in the subway.” One of the men answered, “It’s a shame, and I want to tell you, miss, that we’re going to vote for woman suffrage.”

In 1916 the 72nd Street and Broadway neighborhood was, for the most part, still affluent. That prompted an over-zealous policeman, Albert Buchanan, to arrest two newsboys from in front of the kiosk on February 27. He charged them with “selling newspapers in a loud tone of voice” that disturbed the peace. But when Buchanan brought the boys before Magistrate Murphy, it was the policeman who received the heat.

Asked why he had brought them to court, Buchanan said, “Why, they were selling papers, in a loud tone of voice.”

“What do you want them to do, go up to their customers and whisper in their ear?”

“No,” replied Buchanan, “but your Honor, there have been complaints about the noise up there.” Before he could finish, Murphy interrupted.

“By whom? By a lot of old cranks, I suppose. Why do they not go up to Riverside Drive and complain about the noise up there? The idea of stopping a boy selling newspapers! There is enough competition without making it harder for a newsboy. It is a shame to bring them here. Discharged!”

One of the men answered, “It’s a shame, and I want to tell you, miss, that we’re going to vote for woman suffrage.”

While it seemed that most Upper West Siders had gotten used to the station, there was one who decidedly had not. On May 31, 1919, Owen Jones wrote a short letter to the editor of The Sun that read:

Sir: Give a though to Broadway? Yes, when the worst eyesore is removed that is a menace to life and limb as well. I refer to the Seventy-second street subway station in the middle of the street. Ugly, dangerous, inconvenient.”

As had been the case with James Munroe years earlier, Jimmy Ryan caused women to faint in fear in the station on November 9, 1921. It seems that the results of the election released a day earlier had upset him greatly and he sought solace in a bottle. But Depression era bootleg liquor could have devastating effects.

The New-York Tribune reported that Ryan “came down the subway stairs with his hands clenched.” On the platform he began shadow boxing, at one point smashing his fist into an iron pillar. The article said, “a moment later he had reeled about and was looking into a mirror of a chewing gum automatic vendor. The next minute, without a moment’s hesitation, Ryan’s left flew out and struck the reflected face squarely on the nose.”

But none of his bizarre actions compared to what happened next. An incoming express train caught his attention. “Watch me stop the red-eyed monster!” he shouted and jumped down onto the tracks. The article said, “a number of women shrieked, several fainted, and others began a rush for the stairs.” As Ryan bounded along the tracks toward the train, the motorman was able to stop it within a few feet of where Ryan finally stopped, taking “a fighting pose.”

He was taken to the West Side Court. Magistrate Corrigan commented, “Terrible liquor,” to which Ryan replied, “Terrible election.” The New-York Tribune reported, “Ryan offered to pay any fine from a large roll of bills which he drew from his pocket, but the court decided that his condition did not warrant his release. He was sent to the workhouse for two days.”

As the decades passed, Upper West Siders and New Yorkers in general grew to cherish the little Flemish structure. After years of having been denigrated, Heins & LaFarge’s picturesque subway kiosk was designated an individual New York City landmark in 1979, and the following year the interiors were placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Landmarks Timeline

Keep Exploring

Designation Report

Dig deeper into history!

Read the LPC Designation Report of this Interior Landmark:

IRT Subway Interiors