The Van Koven Apartments

by Tom Miller

By the 1890’s, architect Clarence F. True was well-known, especially on the Upper West Side, for his creative adaptation of historic styles. His scores of private homes, many of them opulent, drew from the Elizabethan, Tudor, Gothic, and other periods. At the turn of the century, he applied his art to an apartment and store building on the east side of Broadway, between 107th and 108th Street. Completed in 1901, the seven-story Van Koven was faced in brick above the stone-clad ground floor. True echoed Georgian architecture with the broken pediment above the paired, second-floor openings, and in the Gibbs surrounds of the central windows of the third through sixth floors. The projecting, five-story bays that flanked the mid-section caught breezes during warm months.

There were two stores at street level, and two apartments each on the upper floors—one of seven rooms and the other of eight, each with one bath. An advertisement noted they were “equipped with every modern improvement, including all-night elevator and hall service; parquet floors, &c.” “Hall service” meant that uniformed “hallboys” were on duty to run errands, deliver packages, mail letters, and do other miscellaneous errands. Annual rents in 1903 ranged from $780 to $900 (about $2,400 per month on the higher end in 2022).

In 1904 brothers Gustave and Henry Stillgebauer purchased the building, renaming it Sherwood House.

In 1904 brothers Gustave and Henry Stillgebauer purchased the building, renaming it Sherwood House. It was most likely a nod to the upscale residential hotel that had stood on Fifth Avenue at 44th Street until 1896, where the elegant society restaurant Delmonico’s had been. At the time, one of the stores was occupied by the William H. Van Last & Co. real estate office, which would remain until 1907.

The residents of Sherwood House were all well-do-to. In fact, the 1911 Dau’s New York Blue Book, which listed members of society, included all twelve of the families living here. Typical of the residents was Mary D. Burchenal, her daughter Elizabeth, and her two sons, Seldan Day and Charles. Born Mary E. Day, she was the widow of influential attorney Charles Henry Burchenal, who had died in 1896.

Unlike so many young women of affluent families, Elizabeth Burchenal embarked on a career. She was appointed the inspector of the Public Schools Athletic League for Girls. When America entered World War I, her brother Selden joined the 51st Aero Squadron of the United States Army and was deployed to Europe. The New York Times reported on May 22, 1919 that Captain Burchenal “returned in January and received his honorable discharge from the service.” He immediately proposed to the sweetheart he had left at home. On March 19 The Sun reported on his engagement to Amy Clare Hutton, who “was introduced to society several years ago, and is actively interested in war relief work.” The wedding took plate on May 21 and society pages reported extensively on the ceremony in St. James Episcopal Church on 71st Street and Madison Avenue. The New York Times noted, “A breakfast for the families and bridal party followed at the home of the bride’s mother, Mrs. Burchenal.”

In September 1920 the architectural firm of Gronenberg & Leuchtag was hired to make interior alterations to the building. Each of the sprawling apartments was cut in half, creating four apartments per floor. An advertisement listed a four-room apartment at $100 per month, or about $1,350 in today’s money. Nevertheless, the tenants were still affluent enough to afford domestic help. A help-wanted advertisement appeared on April 11, 1921 seeking, “Houseworker, experienced white girl, private family apartment.”

That would all change in 1941 when the Sherwood House was converted to a single-room-occupancy building, with 15 rooms per floor. It now went simply by its address, 2790 Broadway. The building that had once appeared in newspapers because of coming-out parties and society engagements, was now connected with disreputable incidents.

He told the court there was no register at the desk and “it wasn’t customary for us to ask names on transients.”

Such was the case on March 23, 1942, when the building was part of the testimony in the murder case against John Cullen, alias B. Adams, and Eli Shonbrum alias Ted Leopold. The indictment against them said the men “wilfully [sic], feloniously and of malice aforethought struck and killed Susie F. Reich by beating, binding, choking and suffocating her.” Wilkie Davidson, the elevator operator at 2790 Broadway, told of the defendants’ bringing a woman to the building on March 4 at 2:00 in the morning and renting a room. He told the court there was no register at the desk and “it wasn’t customary for us to ask names on transients.”

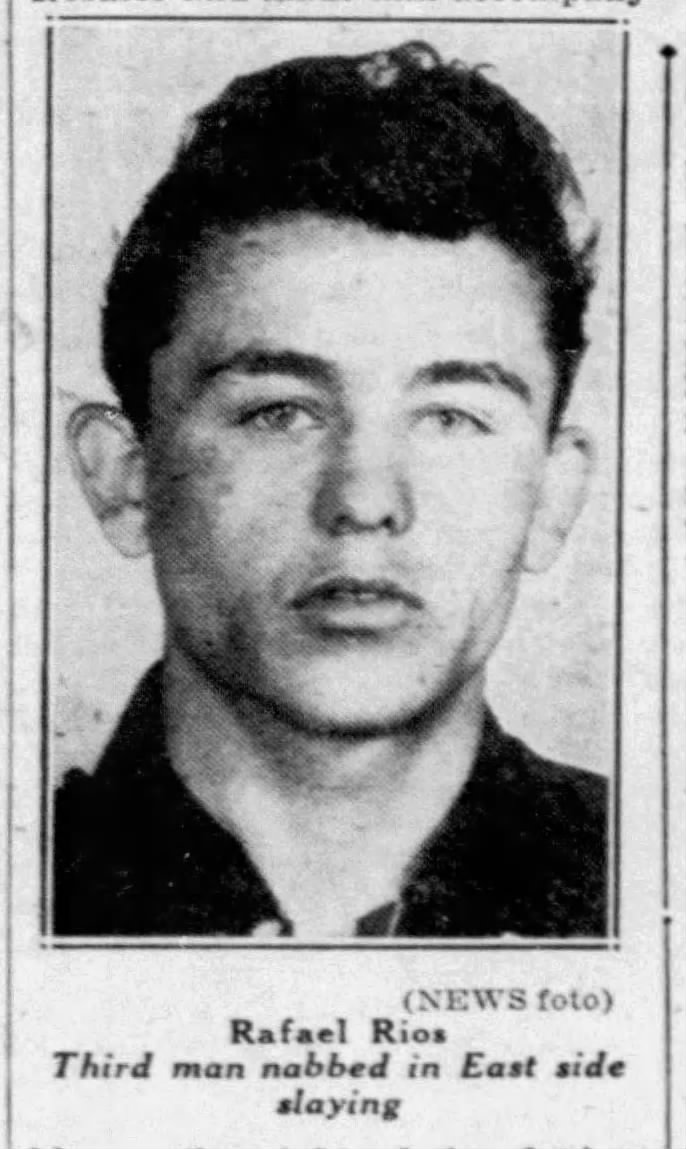

The address came up again in an armed robbery case in 1959. Detective Joseph Robinson testified to going to 2790 Broadway on September 2 in his search for Rafael Rios, alias “Blue Eyes,” who had been renting a room here.

Change came after the building was sold in the spring of 1961. A renovation was begun that would result in ten apartments each on the upper floors. Completed in 1968, the modernization stripped away Clarence True’s charismatic façade and replaced it with a lifeless grey-brick veneer typical of the period. The apartments are cooperative, today.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Meet Mark Linde!