The Cleburne

by Tom Miller

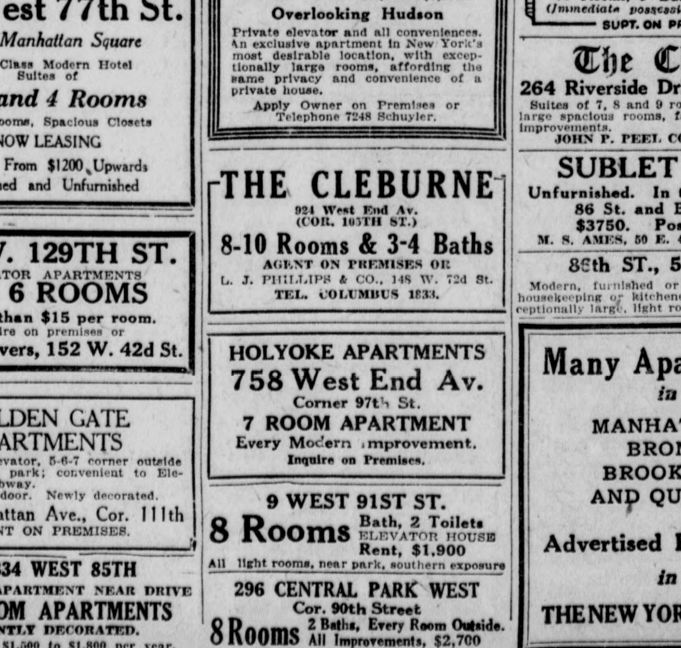

The architectural firm of Schwartz & Gross was exceedingly busy designing apartment houses in the early years of the 20th century. On a single day, November 8, 1912, the partners filed plans for five apartment buildings, all of them on the Upper West Side. Among them was The Cleburne, designed for real estate developer Harry Schiff. The ambitious project would stretch through the block from Broadway at 105th Street to West End Avenue. Twelve stories tall, the architects projected the construction costs at a staggering $750,000. But by May 1913, according to the Real Estate Record & Guide, the figure had risen to $1 million—or about $27.5 million today. The journal anticipated that the structure would be “of a fitting character for so prominent a site.”

The Cleburne was completed in 1913. Schwartz & Gross’s tripartite Italian Renaissance design included a three-story, stone-faced base with stores on the Broadway side (the residential entrance was on the quieter West End Avenue elevation). The eight-story mid-section was clad in brown brick and decorated with occasional stone balconies. The top section, delineated by a balcony that girded the building, was decorated with elaborate carvings. Two deep light courts cut into the building on West 105th Street, giving the initial impression of three separate structures. A deep automobile turn-around—like an immense porte-cochere—on West 105th Street protected residents and their guests from the elements. Apartments in the Cleburne ranged from six to ten rooms, with as many as four baths.

The northern store was leased to Benjamin Ackerman for his delicatessen, while next door was the upscale jewelry shop of David Bumbiner. The apartments filled with a wide variety of tenants.

Among the early residents were George W. Lederer and his wife, whose professional name was Reine Davies. The Cleburne was conveniently close to the motion picture studios in New Jersey, Brooklyn and the West Side of Midtown. On May 21, 1915, Reine received a significant scare while she was filming a Western, Sunday, in Fort Lee, New Jersey. The New York Times reported on May 26 “Miss Davies was riding a bronco and was thrown some distance when the animal bucked too realistically.” The actress suffered two broken ribs and internal injuries, but the article said, “it was thought that she was now out of danger.”

Also living in the Cleburne was Dr. Hubert V. Guile. He was called to the hotel room of a prominent patient in the summer of 1916—former President Theodore Roosevelt. The New York Times, on June 17, reported that Roosevelt’s illness “is by no means a cause for alarm. He is doing very well, according to Dr. Hubert V. Guile of 924 West End Avenue, who is in charge of the case.”

“Miss Davies was riding a bronco and was thrown some distance when the animal bucked too realistically.”

Roosevelt was taciturn on the subject, telling reporters, “I am out of public life, and wish now to be regarded a private citizen. I have nothing to say.” Dr. Guile downplayed the situation as well:

Colonel Roosevelt’s whole condition is irritable, but not serious. A tempest is being made out of a teapot. He has an irritable cough, originating in the region of the larynx. During a violent spell of coughing, he broke one or two strands of a left rib. Naturally when he coughed or moved that rib is painful and distressing. It is purely a local condition and any idea of his going to a hospital is ridiculous.

David Gumbiner’s jewelry store was described by the New-York Tribune as “a place of some consequence, and the luxury of its window displays is a matter of much neighborhood admiration and proper pride.” On May 25, 1920, five gunmen entered David Gumbiner’s jewelry store and made off with $21,000 in jewelry—a quarter of a million-dollar heist in today’s money. The men were apprehended one-by-one, the last managing to escape detection until May 1921.

And then, two days before Christmas 1922, an even more brazen burglary took place. Broadway was packed with pedestrians and David Gumbiner had “a shop full of clerks and Christmas shoppers.” Three men mingled outside among what the New-York Tribune called “the throngs of belated Christmas shoppers and Broadway wayfarers.” They waited until Patrolman Owen Rafferty walked to the northern end of his beat—109th Street—then committed what today would be called a “smash and grab.” The New-York Tribune recounted, “One man threw a brick wrapped in two towels through Gumbiner’s window. Another grabbed two trays loaded with expensive trinkets, while a third watched the doorway of the store, one hand held significantly in his coat pocket. None of the three wore overcoats. They were equipped for rapid movement.”

The crooks had parked their getaway car across Broadway. They piled into the automobile and fled, pursued by one of Gumbiner’s employees, William Aschendorf, on foot. It was, of course, a fruitless attempt. The New-York Tribune reported the theft of “$15,000 worth of diamonds and other precious stones.”

In the meantime, more drama was playing out upstairs. Stockbroker and head of the Mayo Security Ink Company, Roy Alfred Mayo and his wife, Charlotte Catherine, were having domestic problems. The couple had been married on July 11, 1916 when she was 18 and he was 46. The New York Times said that Charlotte was “said to be an heiress in her own right.” The couple maintained “a handsome Summer home at Shippan Point, Stamford, Connecticut.” Charlotte was his second wife, his first having died in 1911. Along with their two-year-old daughter, Charlotte, living with them in their Cleburne apartment were Mayo’s 16-year-old daughter, Mercedes, and 23-year-old son, Rutledge.

The first installment of their soap-opera-worthy difficulties became on July 2, 1921. The New York Times reported that Charlotte “quitted her home in the fashionable Cleburne apartments.” She returned three days later in the company of two private detectives to snatch little Charlotte. “While a limousine waited at the curb, its engine running, she went to the apartment and lifted the child from the bed on which it was taking an afternoon nap.” The article said neither the servants nor Mercedes, who was at home, “offered any resistance.”

While Roy Mayo put private detectives on the case, he filed for divorce. The New-York Tribune reported on July 16, “He alleges indiscretions at various times on the part of the defendant.” Exactly one month later, Mayo’s detectives tracked the toddler to the home of her 90-year-old great-grandmother in Walls, Mississippi. She had been brought there by Charlotte Mayo’s mother, Mrs. E. S. Cheatham. The detectives re-kidnapped the child, taking it by automobile to Memphis, where they boarded a train to New York City.

Charlotte Mayo had moved into her mother’s apartment at 131 Riverside Drive. A week after the little girl had been returned to her father, Mrs. Cheatham (who, parenthetically, was younger than Roy Mayo) went missing. The New York Herald reported on August 22, 1921, “The clothing of a woman believed to be that of Mrs. E. S. Cheatam…maternal grandmother of Charlotte Mayo, the much kidnapped daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Roy A. Mayo, was found late last night in a locker in Richman’s Baths, West Fifth street, Coney Island.” Charlotte Mayo went to Coney Island and identified the clothing as her mother’s. The only explanation she could give was that “she might possibly have committed suicide over the loss of her granddaughter, Charlotte Mayo, 26 months old, who, she charges, was kidnapped by Mr. Mayo recently.” Mayo claimed that it was a hoax to gain sympathy and recounted the time that Mrs. Cheatham had faked a suicide in Chicago after she was convicted of shoplifting.

The family’s name was in the newspapers again the following week. The tumult at home may have proved too much to bear for Rutledge. On August 28, 1921, the New-York Tribune reported that he and Thelma Wysong had eloped. Mercedes was the maid of honor.

The drama only continued. Mrs. Cheatham, presumed drowned, was found (just as Roy Mayo had predicted) hiding in Chicago. In response to the divorce suit, Charlotte requested $20,000 in alimony and $10,000 in counsel fees (the equivalent of $434,000 today). And then, on May 3, 1922, The New York Times reported that Mayo had been arrested in Stamford, Connecticut, “charged with conspiracy and obtaining money under false pretense.” It had to do with a sale of worthless stocks in ink companies.

Mrs. Cheatham, presumed drowned, was found (just as Roy Mayo had predicted) hiding in Chicago.

Much less colorful residents at the time were Edgar H. Cottrell and his wife, the former Leona Balfe. The couple had four children. Cottrell was well known in the printing industry for his several inventions. The New-York Tribune said his “inventions and development of presses revolutionized the printing of national magazines.” He made it possible to print magazines on rotary presses, as was already done with newspapers, and perfected a process for multi-color printing on a rotary press, for instance.

Living with Frank E. Ward and his wife in the early 1940’s was Ward’s mother-in-law, Louisa A. Corby. Born Louisa A. Meinberg in Hanover, Germany, she was brought to America as an infant. When she was 17 years old, she married Israel Corby. Their domestic life was interrupted when Corby joined the 89th New York Regiment to fight in the Civil War.

On September 15, 1946, the Wards hosted Louisa’s 102nd birthday party “with friends and relatives,” said The New York Sun. The newspaper noted that she was “able to read with the aid of glasses and preferred the Bible to all other books.” Louisa died in the Wards’ Cleburne apartment three months later December 9.

Filmmaker Michael Snow and his wife, Joyce, lived in the apartment of Graeme and Betty Ferguson here in the mid-1950’s. Considered by some today as one of history’s most influential experimental filmmakers, Snow was working as a free-lance filmmaker at the time. The Snows remained until around 1963 when they moved to 191 Greenwich Street.

Living in the Cleburne at the same time was composer, pianist, and music instructor Sergius Kagan. He had been on the staff of the Juilliard School of Music since 1940 as a teacher of voice, vocal literature and the literature and materials of music. His first opera, a musical version of Hamlet, was produced in Baltimore in 1962.

On February 1, 1960, author Madeleine L’Engle and her actor husband Hugh Franklin moved into a $128-per-month apartment in the Cleburne. While here she completed her most famous novel, A Wrinkle in Time. In addition to her writing, she taught at St. Hilda’s & St. Hugh’s School. In the meantime, Hugh Franklin worked in television in films, replacing Melvyn Douglas in Gore Vidal’s The Best Man, for instance.

In 1988 Birdland opened at 2745 Broadway. The jazz club became a destination spot, drawing music lovers into the mid-1990’s. On January 6, 1995, Newsday wrote, “One of the more intriguing dates this weekend takes place Uptown at Birdland…tonight and Saturday where pianist Joanne Brackeen fronts a combo consisting of Saxophonist Ravi Coltraine, drummer Tony Reedus and bassist Ira Coleman.”

A celebrated tenant arrived in October 2012 when comedian Andy Borowitz and his wife bought an apartment in the Clebourne (an “o” was added at some point) for $2.6 million. They joined a growing list of celebrities in the building that included actress Estelle Parsons, here at the turn of the 21st century; The Wiz composer Charlie Smalls; and journalist couple Norman Podhoretz and Midge Decter.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 2741-2747 Broadway:

Meet Glenda Sansone!