The Edison Theatre Building

by Tom Miller

In May 1911, architect William Gray filed plans for an “open air picture show” on the northeast corner of Broadway and 103rd Street for James Edward Schriwen. The project was estimated to cost Schriwen about $45,000 in 2023. The venture, however, apparently failed, for two years later Henry W. Hodge hired Edward P. Casey to design what his plans called a “two-story brick store and moving pictures” building on the site.

The completed structure was clad in terra cotta, its neo-Classical details including Ionic pilasters between the openings of the second floor that dripped bellflowers. The theater entrance was at the north end of the building, providing ample space for shops along Broadway and on 103rd Street. The upper floor held office and studio spaces.

Briefly called the Riverside Theatre, the name of the 610-seat venue would change repeatedly. By 1916 it was the Broadway Photoplay Theatre, quickly followed by B. K. Bimberg’s Broadway Theatre in the early 1920s. One of a chain of theaters owned by Bernard K. Bimberg, it was familiarly known as Bim’s 103rd.

In the meantime, the stores and offices were leased to a wide variety of tenants. The American Florist moved into 2696 Broadway in 1914. Next door at 2694 was Dietrich Muller’s candy store. The corner space was occupied by the F. K. James Co. drugstore starting in 1915.

On the morning of May 19, 1914, Dietrich Muller stopped by the candy store to visit. Concerned when he found the door locked, he went for help. The Evening World reported, “A locksmith opened the door and found Muller dead behind the counter. He had inhaled gas from a tube connected to a hot water heater.”

On the night of November 12, 1921, a cabbie, Jacob Sagor, took two crooks to the Broadway Restaurant at 32 Cathedral Parkway where they held it up.

Upstairs, the C. & D. Dance Studio occupied space by 1917 and would remain into the mid-1920s. It offered private and class instruction in “social dancing, interpretive dancing, classic technique” and “baby classes.” Run by “Coleman and Danielson,” the studio offered special rates for Columbia students. Also upstairs in the early 1920s was the Clair Marcelle photo studio. It advertised a dozen portrait prints for $20.

At the street level at the time was the Academy Restaurant at 2698 Broadway, a Lerner women’s clothing shop in 2694, and the Donniebrook Men’s Shop next door at 2694.

On the night of November 12, 1921, a cabbie, Jacob Sagor, took two crooks to the Broadway Restaurant at 32 Cathedral Parkway where they held it up. From there, he drove them to the Academy Restaurant. The armed robbers were most likely disappointed—they got $20 from the first cash register and $35 from the Academy. Jacob Sagor was arrested when his license number was traced. Whether his accomplices were found is unclear.

One of the upstairs spaces was Coyne’s Hall, an Irish-American social hall, in the early 1930s. An advertisement in the Irish newspaper The Advocate on November 26, 1932, touted a “West of Ireland Social and Dancing” with Irish music by Tom Harrison and His Orchestra and American music by Edmund Tucker. Admission was 25 cents.

A month later, the hall changed hands and names. On December 31, The Advocate reported, “The Clare Hall, at 2700 Broadway, at 103d street, formerly ‘Coyne’s,’ housed a dandy crowd on Sunday night. Jim Duffy, the well-known G. A. A. [i.e., Gaelic Athletic Association] man, is now general manager.” A separate article noted that Clare Hall “will be open every Thursday, Saturday and Sunday evening for dancing.”

By then, the theater had become the Essex, and by 1941 was the Edison Theatre. Among the tenants in the long row of shops were the Ekim Bar and Restaurant, and the Newport Clothing shop. Michael J. Freeman opened the Ekim Bar and Restaurant in 1934. After operating his business for nearly three decades, he lost his liquor license on February 23, 1962. The State Liquor Authority charged that on September 30, 1961, he had permitted “homosexuals, degenerates and/or undesirables to be and remain on the licensed premises.”

Michael J. Freeman went to court. The undercover vice detectives testified, as did multiple witnesses for the defense, including bartenders and patrons. The detectives’ stories gradually fell apart, and one was forced to concede that, in fact, he had not heard males use female names nor talk in “high pitched voices.” The case was dismissed the Freeman’s liquor license was reinstated.

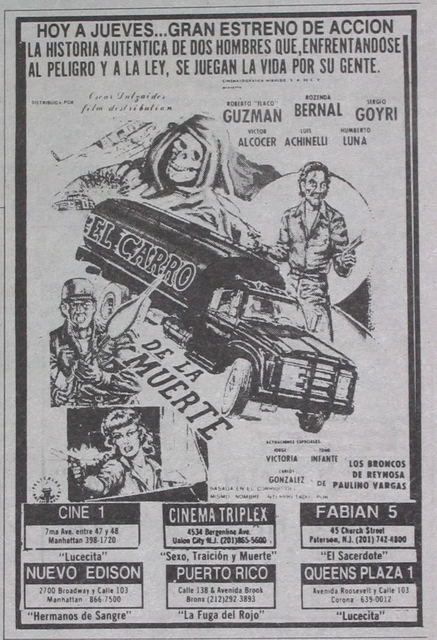

The changing demographics of the neighborhood were reflected in New York Magazine’s saying on February 19, 1979, that the Edison Theater “was known for years as Bimberg’s 103rd Street Theatre. It is now a clean, well-kept house showing Spanish films, and it holds festivals of golden-age Mexican films.” And while the marquee still read Edison Theatre, the venue was widely known as the Nuevo Edison.

The State Liquor Authority charged that on September 30, 1961, he had permitted “homosexuals, degenerates and/or undesirables to be and remian on the licensed premises.”

On August 3, 1987, New York Magazine reported, “Last week, the neighborhood’s transition got another push when the Nuevo Edison, a Spanish-language movie house on Broadway near 103rd Street, reopened as the Columbia Cinema.” The theater had been closed for a year as Nicos Nicolaou and Ralph Donnelly of City Cinemas spent half a million dollars in renovations. The article said, “The Columbia, with Doby sound and reupholstered seats, will feature first-run movies in English (the premiere show is La Bamba).”

The Columbia Cinema did not turn its back on the Latino locals, however. The following year, on November 18, 1988, The New York Times journalist Richard F. Shepard reported that El Museo del Barrio would be hosting the 1988 National Latino Film and Video Festival here.

Despite the makeover, the Columbia Cinema could not compete with the modern multiplex theaters opening around the city. It closed in 1993. A Lucille Roberts gym leased a large amount of space in the building after that, while other businesses along Broadway included a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet and several small “mom and pop” shops.

Then, on December 15, 2002, The New York Times reported that Columbia University, which had already announced plans to build a residence hall for faculty and graduate students, was eyeing “the half-block site, at 2700 Broadway at 103rd Street.” Before long, the two-story building was gone, replaced by a residential structure designed by Costas Kondylis & Partners.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2700 Broadway: