The Hotel Marseilles

by Tom Miller

In 1899 millionaire William Earl Dodge Stokes had a vision. He foresaw Broadway, at the time called The Boulevard on the Upper West Side, as New York’s answer to the Champs-Elysses. For his part he imported French architect Paul E. M. Duboy to design the massive Ansonia apartment building on Broadway at 73rd Street–a frothy French concoction 17 stories tall.

The Ansonia sparked the rise of similar French-style apartment buildings facing Broadway. As it rose (construction would take five years) the Netherlands Construction Company purchased the large plot of land at the southwest corner of Broadway and 103rd Street and set architect Harry Allan Jones to work designing an upscale “apartment hotel.”

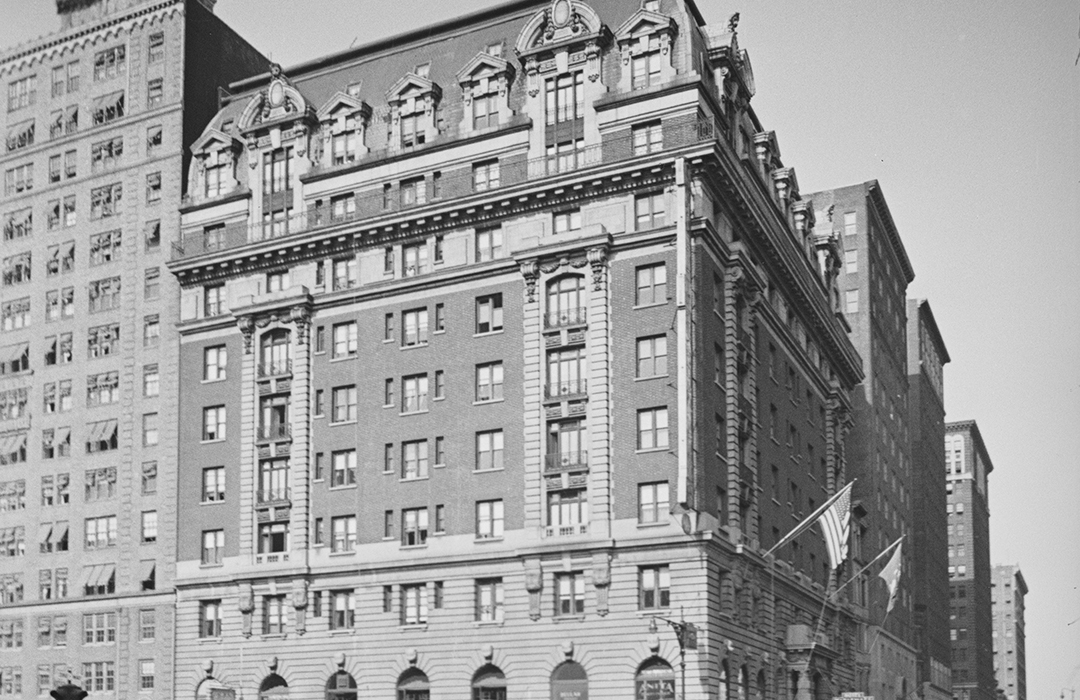

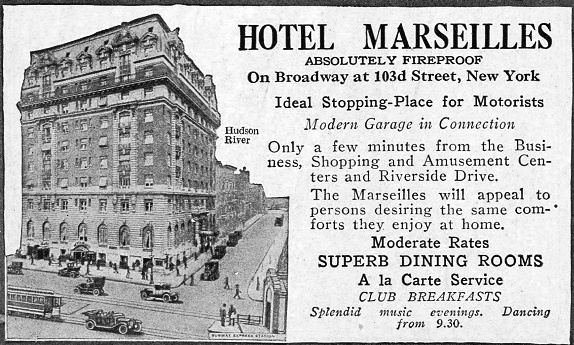

Construction began in 1902 and was completed three years later. While decidedly less exaggerated than the Ansonia; the 11-story structure carried on the French motif right down to its name: The Hotel Marseilles. The three-story base of rusticated limestone included shops along Broadway and an elegant entrance on 103rd Street adorned by a portico of banded columns. (The portico would be nearly duplicated in the strikingly similar apartment Kenilworth Apartments designed by Townsend, Steinel & Haskell, completed in 1908).

The four-story central section was clad in warm red brick that gave way to the contrasting white stone above the seventh-floor cornice. The high, sloping two-story mansard featured dormers, the most dramatic of which broke through the cornice and wore bold, arched pediments.

In October 1905, just as the finishing interior touches were being completed, the Netherlands Construction Company leased the building to hoteliers Louis Lukes, of Milwaukee, and New Yorker H. C. Griswold. The men formed the Marseille Hotel Company (forgetting to use the “s” at the end of Marseilles) for the project.

The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide described a few of hotel’s amenities: “A rathskeller, grill-room, billiard-room, cafe, barber shop and one of the best-equipped kitchens in the city occupy what is called the cafe floor of the Marseilles.” The ceilings of the main floor were 18 feet in height. On this level were “palm and reception-rooms, a spacious lobby, telegraph and telephone rooms.”

Also on the main floor were a public dining room as well as several private dining rooms. More private dining rooms were found on the mezzanine. These were a necessity in residence hotels where few apartments contained kitchens. The allure of upscale apartment living was the relief from maintaining a domestic staff. Residents could forego help like cooks, laundresses, and cleaning maids.

The Hotel Marseilles was intended for upper-middle class residents. While apartment buildings like the Kenilworth had just three house-sized apartments per floor, there were 17 suites to each floor of the Marseilles, ranging from just one to three rooms each.

Perhaps because of those small suites, the hotel seems to have been more popular with transient tenants than full-time residents. One of the early guests would cause months of mystery and speculation in the newspapers. Blanche Turner Dennis was the widow of Major Hugh C. Dennis, at one time one of the highest-salaried life insurance agents in America. His was a peculiar death, The World saying that he “grieved himself to death” after an investment scheme failed.

Blanche, whom The World described as a “young woman of thirty, beautiful of face and figure,” arrived at the Hotel Marseilles on February 17, 1906. The newspaper hinted “she is supposed to have come here to conceal a secret.”

That secret was her pregnancy. Her husband had been dead two years, so there was no explaining away her condition.

Hotel employees remarked that Blanche arrived “gowned in the latest style. She seemed to have an unlimited supply of money, and she looked the woman of refinement.” She was given a room on the seventh floor. Once there, she had no callers and kept to herself.

Four days later a doctor was called to the hotel. Newspapers carefully avoided words like “pregnant” or “abortion;” instead tiptoeing around the situation, while leaving no doubt in their readers’ minds as to what had happened.

The World reported “The physician saw at once that Mrs. Dennis was suffering from drugs and an operation of a criminal nature, and she admitted that she had administered [it] to herself.” Although Dr. Kidder treated her for several days using “heroic methods,” it was clear on March 28 that she was dying.

In the early years of the 20th century, a convenient method of obtaining a relative’s wealth was to have him or her declared insane.

The coroner was called to the Marseilles, not to witness her death, but to get a dying statement. In 1906 the man responsible for her condition would have been a guilty party in the crimes of suicide and abortion. The coroner was, however, frustrated in his cause. The Evening World reported on March 29 “If there had been a time when she could make such a statement she would not talk. She seemed to want to die with her secret.”

Blanche died that evening; but detectives had not given up. A newspaper noted “In her trunks are believed to be letters which will tell of a St. Louis scandal.”

Remarkably, the suicide resulted in a related tragedy and headlines. Another young widow, May Kay was staying in the Hotel Alabama and she was a friend of Blanche Dennis. On the morning following Blanche’s death, a woman called Coroner Shrady and asked if she had suffered great pain. Rather indiscreetly he told her yes, she had. He told police later that the caller then “burst into tears, and was able to give her name with difficulty.” Her name was May Kay.

That night May put a pistol to her head in her room in the Hotel Alabama.

An investigation to find Blanche’s lover rounded up local suspects, even though she was not from New York. The New York Times reported on April 11 that “The Baron de Cartazzi will also appear as a witness this morning before Coroner Shrady in the inquest to be held over the late Mrs. Blanche Turner Dennis, a widow who died suddenly in the Hotel Marseilles last month.” The newspaper later reported that “A number of prominent bankers, insurance men and politicians were examined at the same time.”

Another high-level person questioned was wealthy financier Joseph G. Robin. The Evening World described him as having “no time to marry or to spend in the society of women,” and said he “was very indignant when questioned by Coroner Shrady.”

Later that year, in September, the hotel received more unflattering publicity. In 1879 Grace Sterling Bixby had become one of the first “penny princesses”– the wealthy socialites who married foreign titles–when she was wed to Count Casimir Ignace Mankowski. When Count and Countess Mankowski arrived in New York from England with their youngest son, Robert, they headed to the Hotel Marseilles.

The Countess’s wealth came from the $3 million estate of her father, which gave her an income of $100,000 per year (more than $2.7 million today). John M. Bixby’s estate also bequeathed her valuable Manhattan properties like the Union League Club and the Casino; and extensive Murray Hill real estate.

In the early years of the 20th century, a convenient method of obtaining a relative’s wealth was to have him or her declared insane. Only a week after the family moved into the Hotel Marseilles, the Count petitioned the court to have his wife committed. On September 15 Justice Dowling of the Supreme Court appointed a commission “to inquire into the sanity of the Countess Grace Sterling Mankowski.”

While The New York Times described her as “an exceptionally bright woman;” the count said “She is unable to read or write or maintain a coherent conversation.” A sheriff’s jury ruled her “incompetent.” However instead of turning over the administration of her affairs to her husband, it put her two adult sons in charge.

In 1908 Joseph Hamerschlag foreclosed on the Netherlands Construction Co.’s outstanding $638,716.12 mortgage. He took back the property and briefly renamed the building the Hotel Langham. Within the year he rethought that idea, and returned its name to the Hotel Marseilles.

Among the elegant entertainments held in the Hotel Marseilles, was the “orchid tea” in the Palm Room given by George Levy to celebrate the debut of his only daughter, Rena Geraldine, on February 6, 1909. The Times society column reported “The room, with its cathedral glass dome, was lighted with hundreds of tiny electric bulbs, the wall lights were shaded with orchid-tinted silk shades, and pendent from them were bunches of purple orchids and maidenhair fern. The tea table was banked with masses of the same blossoms.”

But it was repeatedly unwanted publicity that landed the hotel in headlines. In September 1911 a 38-year old Boston woman came to New York with hopes of becoming an actress. She checked into the Hotel Marseilles then headed off to land a place on the vaudeville stage.

The Evening World explained on October 23, “For six weeks she travelled up and down the weary round of offices in the Rialto, a journey unfavorably known to many in the theatrical profession.” Mrs. A. E. Necker had spent $500 on costumes “to dress the act” and pitched her act to managers and booking agents. Each told her that her act was “a novelty” and would probably success. Yet none was willing to back her.

To survive, she sold off her jewelry piece by piece. As her desperate financial circumstances worsened and the dream of success on the stage faded, the pressure became too much. On Saturday morning, October 21, she was found in the third floor waiting room, “laughing hysterically and unable to speak.” A journalist who witnessed her answering every question with “wild laughter” opined “at last the realization of her alarming conditions, inevitable poverty, oncoming age and life spent in failure, became too great for her reason.”

Mrs. Necker was taken away to Bellevue Hospital, well-known for its insanity wards. The Evening World warned would-be actresses, blinded by the limelight. “Beneath this apparently simple announcement lies a tragedy as pitiful as is typical of the quest for fame in New York. It carries the three ever recurring themes–poverty, the lure of the stage and vanished youth.”

The hotel continued as a popular venue for dinners and meetings, like dinner of the Men’s League for Woman’s Suffrage on March 21, 1912. “A feature was the wearing by each of the diners of a yellow paper hat, indicative of the pledge to get the right of suffrage for women,” noted the New-York Tribune.

The following spring Manager Charles A. Weir announced that a roof garden would be installed. The Real Estate Record & Guide reported “The garden will be decorated in the usual manner, with latticework and foliage, but several new ideas will be incorporated in the lighting effects and the service.”

At the time the Hungry Club held its monthly dinner meetings here. The group received permission to hang a large oil portrait of General Robert E. Lee, painted by a member, in the large dining room. It was the focus of an incident in June 1914 that gave The New York Times fodder to lampoon vacuous socialites.

The newspaper said “Recently a lady in the west side gave a bridge party at the hotel in aid of her pet charity.” Among the guests, said the article, was “a typical ‘climber’ with considerably less education than cash. Consequently she was never backward with misinformation on most any subject that came up.”

Between hands one player vocally admired the portrait and wondered aloud who the subject was. The unnamed “climber” was quick to respond. “That, my dear, is General Marseilles, a noted Frenchman, for whom the hotel is named.”

The hotel was the scene of a tragic and avoidable event on October 30, 1917. Berney B. Loveman was 25 years old and a corporal in the United States Army. His father owned Alabama’s largest department store.

When he was furloughed on Sunday October 28 he rushed to New York City and proposed to his sweetheart, Regina Glanckopf, and she happily accepted. Corporal Loveman had been in the military for four years and was about to be deployed to France. The Evening World noted “She and the young soldier were eager to have the ceremony performed.”

They obtained a license and Loveman purchased two wedding rings, engraved “R. G. and B. B. L.” But then her parents, possibly concerned that Loveman would not return from the front, insisted they wait to marry until the war ended. Thinking that his mother’s support might sway the Glanckopfs, he telegraphed her. To his extreme disappointment she wired back saying she also thought it best to wait.

On October 30, with his furlough running out, he telegraphed his mother again. He waited all day for an answer, then had dinner with his future in-laws and fiancé. The telegraph from his mother never came. Eight hours after leaving the Glanckopf house, at around 3:40 in the morning he went to the Hotel Marseilles. Regina was to drive him to Camp Mills on Long Island, later that day.

Instead, Loveman went directly to his eighth floor room and jumped. He was instantly killed when he landed on the 103rd Street sidewalk.

The hotel was the scene of an unusual Christmas party the following year. New Yorkers were accustomed to reading of wealthy women providing parties, dinners and gifts for needy children during the holidays. But Mrs. William Hollis Weeks came up with a different idea that year.

The Sun reported on December 29, 1918 that she “has closed her mansion at Queens and is spending some time in a suite at the Hotel Marseilles, with her family.” While other socialites focused on the poor, the newspaper said “At least one social leader in New York did not forget ‘the poor little rich girl.'”

She decided, according to the article, “to play hostess to the little children who were guests in the hotel.” Management provided a Christmas tree in the Green Room and Mrs. Weeks “twined it with all the glittering ornaments that children love and hung amid its rainbow hued electric lights such beautiful gifts as Santa Clause loves to bestow and children to receive.”

Thanks to Mrs. Weeks the well-off children were “radiantly happy” in the “perfect Christmas fairyland.”

While other socialites focused on the poor, the newspaper said “At least one social leader in New York did not forget ‘the poor little rich girl.'”

In the early years following the end of World War I, the hotel continued to attract the well-do-do. In a somewhat elitist advertisement in 1918, the management stressed “The clientele of the Marseilles is selected with a desire to harmonize personal relationships. Unusual care is taken in accepting those whose presence will be compatible with the highest standards.”

Such careful vetting did not always pan out. Ida Platou was the 21-year old daughter of ship supply dealer Carl Platou when she married Norwegian Fridtjof Bryde, described by The Evening World as a “millionaire ship owner,” on December 27, 1918, just a month after the war ended.

Ida’s two brothers were in the navy and her extended family had worked tirelessly in the war effort. She consented to marry Bryde on the condition that he become an American citizen and that he sail his fleet under the American flag. In the weeks just before the wedding he launched two new ships, one of which was christened by Ida and named in her honor.

Bryde had consented to his bride’s conditions; but then she added more demands during the wedding dinner at the Biltmore Hotel: “that he would live in New York–not Brooklyn or the Bronx, but Manhattan–nine months out of the year. If business compelled it, she was willing he should take a three months’ trip to England or Norway.” He agreed to the new demands as well.

The newlyweds moved into the Hotel Marseilles. But Ida was almost immediately disillusioned. Their unhappy marriage ended when Bryde left home in February and never returned. Ida was in court in May 1919. The Evening World wrote that she alleged that two weeks after moving into the Hotel Marseilles “her husband treated her cruelly because she insisted that he do something to Americanize himself.” She desperately wanted a divorce because “her husband would not keep his promise.”

Ida had a problem, though. Bryde was a citizen of Norway, she was a citizen of the United States. Her separation suit could not be tried in America because, according to Bryde’s attorneys, “the courts of this country cannot separate citizens of a foreign country.”

In 1922 a single room with bath cost $3 and $4 per day. Rooms “with water” (a sink) were an extra $2.50 and $3.00. A double room cost either $5 or $6 a day, “with water $4 & $5.” The $6 double room would be equivalent to $85 a night today.

Not only had the neighborhood around Broadway and 103rd Street changed by the end of World War II, but once-fashionable turn of the century hotels had been surpassed by new structures with modern conveniences. The Hotel Marseilles was taken over by the United Service of New Americans as a refuge for Jewish war survivors.

The stories brought by the hotel’s new residents were often heart-wrenching. An example was that of 24-year old Izak Lanchart and his 22-year old brother Leon. They arrived at Pennsylvania Station on October 2, 1947 and were greeted by United Service representatives and their sister, Celia, and brother Morris. The four had not seen one another in the ten years since they were separated in Germany and Poland.

When they arrived at the Hotel Marseilles and deposited their “hand-stitched suitcases,” The Times said “the brothers first asked haltingly about their parents. Their sister described how their father, Israel David Lanchart, a Hamburg tailor, and his wife were deported to Poland. Then the father died in a hospital. ‘Mother and her three brothers were killed in Auschwitz concentration camp,’ she said.”

In his 1992 book Against All Odds: Holocaust Survivors and the Successful Lives They Made in America William B. Helmreich said of the Hotel Marseilles “Some remembered it as a ‘dilapidated halfway house for war refugees’ where they, nevertheless, felt at ease. Others identified it as the place where they received their first key ever to a private room.”

The facility offered “meeting rooms, recreation halls, medical facilities, offices and a kosher dining hall.” There was also an in-house synagogue. Manufacturers donated new clothing for the new-comers.

Helmreich wrote “Walking around in the lobby and listening to the conversations of immigrants in a dozen tongues gave observers the feeling of being in another world, a world whose inhabitants were unwilling to shed the cultural baggage of the past even as they hesitantly groped their way toward a new life.”

The month following Izak and Leon Lanchart’s arrival many of the refugees in the Hotel Marseilles experienced an American tradition. The Times reported on November 25, 1947 that “Several hundred men, women and children, recent arrivals from displaced persons centers in Europe will observe their first Thanksgiving in the United States.” That afternoon Secretary of Commerce W. Averell Harriman spoke in the dining room.

Of all the Upper West Side’s exuberant turn of the century apartments and hotels along Broadway, perhaps none had a more colorful or often tragic history than the Hotel Marseilles. In 1980 it was converted to apartments for the elderly. Despite some alterations at street level on the Broadway side and a hideous blanket of asphalt shingles on the mansard, the Hotel Marseilles survives as a fine example of the era of William Stokes’s Parisian dream.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Landmarks Timeline

Keep Exploring

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 2689-2693 Broadway:

Meet Cara Brussovansky, LMSW

Meet Elaine Karas!