The Ben Hur

by Tom Miller

In 1899 developer George F. Johnson completed construction on a seven-story apartment building at 2643 and 2645 Broadway (an advertisement noted, “formerly Boulevard”). Simultaneously, author Lew Wallace’s novel Ben-Hur was adapted into a stage play. There can be little doubt that the play’s popularity prompted Johnson to christen his new building the Ben-Hur.

The Renaissance Revival style building was seven stories tall, faced in gray brick and trimmed in limestone. An iron-railed balconette at the third floor fronted the hallway windows inside. There were two eight-room apartments per floor—one on either side of that hallway. To the front were the library, parlor and dining room. A long corridor led to the kitchen and servant’s room, and to three bedrooms. The up-to-date amenities included steam heat, an electric elevator, electric lights and telephone service.

The residents of the Ben-Hur were professional, such as John C. Wilson, the senior member of the hat manufacturing firm John C. Wilson & Co. He had come to New York City from Valparaiso, Indiana in 1883 “with little capital,” according to Men’s Wear magazine. By the time he moved into the Ben-Hur he was highly successful and affluent. Never married, he was concerned about the future of his company and on July 21, 1907, made out a carefully conceived will, leaving shares to “all his important men.” It was a prodigious move.

…fearing that Wilson had heard of the murder and was about to call for police, Warner fired three shots into his torso.

The following day Wilson was sitting in his office when an old client, Frank H. Warner walked in. Wilson knew that Warner had a history of drinking and that his hat store had gone into bankruptcy about 18 months earlier. He attributed Warner’s “agitation to the effects of a spree,” according to The Evening World. He had no way of knowing that less than an hour ago Warner had shot Esther Norling dead after she refused to marry him and set him up in business again.

“Mr. Wilson, I have urgent need of $10,” Warner said. “I want you to lend it to me.”

“Have you reached that extremity?” asked Wilson.

“I am absolutely broke. I must have that amount of money.”

Wilson replied, “All right,” stood up, and turned for the safe. Then, fearing that Wilson had heard of the murder and was about to call for police, Warner fired three shots into his torso. The 59-year-old died in the hospital two days later.

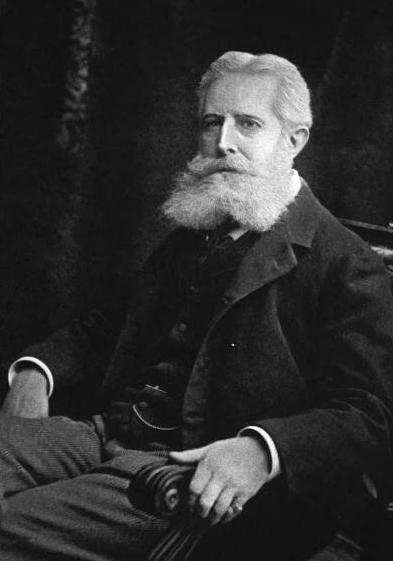

Another resident at the time was poet Edmund Clarence Stedman, whose wife Laura Hyde Woolworth and son Frederick S, had both died in 1905. Friends said he never fully recovered from that shock. Born in 1833, he worked as a journalist and then a stockbroker. But his passion was poetry. His first book, Poems, Lyrical and Idyllic, was published in 1860. In 1904 he was chosen as one of the first seven members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. A Renaissance man of sorts, he also designed a rigid airship in 1879, inspired by the anatomy of a fish. It foreshadowed the later dirigibles of the early 20th century.

He retired from the stock business in 1900, but continued writing, much of it at his country home in Bronxville. He was working on his memoirs in 1908 in his Ben-Hur apartment when, on the afternoon of January 18, “he was stricken suddenly, and died almost instantly, before any aid could be given him,” reported the New-York Tribune.

In 1921 the store at 2643 Broadway was home to Calder & Co.’s “The Shop of Black.” The store sold mourning apparel and accessories. An advertisement in The New York Times remarked, “The well-dressed woman today realizes the exclusiveness of black…Mourning apparel is our specialty, but we also have a full line of Black Hats and Gowns suitable for other occasions.”

In 1921…2643 Broadway was home to Calder & Co.’s “The Shop of Black.”

By 1933 the store was the Fair Dairy, Inc. grocery store. Its proprietor, Max Wilence, repeatedly violated the Office of Price Administration ceiling prices. On September 16, 1946, The New York Sun reported, “He has a record of fourteen previous convictions on price violations, and the concern has paid more than $2,500 in fines.” He was deemed by an OPA enforcement officer as “probably the worst violator of OPA ceiling price regulations in the city.” When he was arrested on his fifteenth charge, the War Emergency Court magistrate had had enough. He sentenced Wilence to ten days in jail and fined him $500 (ten times that much in today’s money). The grocery store would remain in the space into the 1950’s.

By the last decades of the 20th century, the building was showing its age. An inspection of the sheet metal cornice around 1986 demanded its removal. At a time when unsightly scars or patches testified to missing cornices, the building received a glass fiber reinforced concrete replica.

Major change came in 1993 when the building was converted to a 72-bed residential treatment center for mental patients run by the Volunteers of America and the Institute for Community Living. Although the conversion was not initially welcomed by the neighborhood, the facility remains in the building.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2643-2645 Broadway: