2642 Broadway

by Tom Miller

As the turn of the last century approached, the Broadway neighborhood around 100th Street, once part of David S. Jackson’s sprawling country estate, had filled with homes and businesses. In January 1900 Herbert Dongan, principal in the Herbert Dongan Construction Co., purchased the plot at 2642 Broadway from Francis M. Jencks. Eight months later he leased the property to Theodore E. Schutz and Frank Homan as the site of their proposed automobile showroom. Dongan hired architect T. R. Cutler to design the 25-foot-wide “brick storage house” for his tenants. Because he was his own contractor, the structure cost Dongan just $10,000—about $335,000 in 2023.

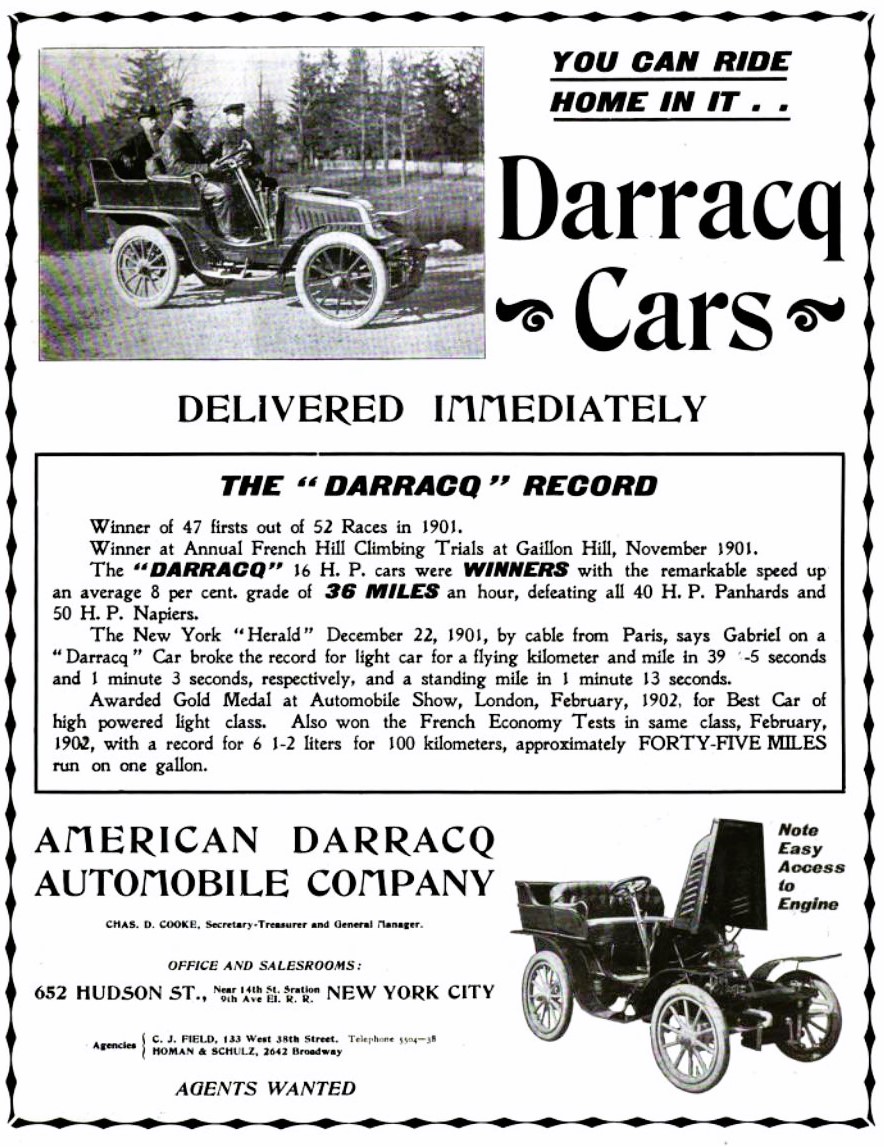

Cutler’s vaguely Arts & Crafts style building featured great expanses of glass at the second and third floors. A garage-type bay shared half of the first floor with a showroom fronted by a large window. Homan & Schutz acted as agents for automobile makers, like the French De Dion-Bouton Motorette Company and the American Darracq Automobile Company. It also provided repair services to vehicle owners.

The building operated as a stable until 1911 when it was purchased by Leopold L. Barzaghi.

The partnership was short-lived. On December 3, 1903, The Automobile reported that Theodore Schutz had bought out Homan. The following year, on October 15, 1904, the Automobile Review announced that Schutz “will open a new garage at Broadway and 110th street,” promising it would be “the most modern place in New York.”

Manhattan still had more horses than motorcars, and the lease on 2642 Broadway was taken by D. & C. H. Fine Co., “horses.” The building operated as a stable until 1911 when it was purchased by Leopold L. Barzaghi. He found a new tenant in Edward Thomas and Thomas R. Wheeler’s New Taxicab & Auto Co. Barzaghi hired architect Harry P. Knowles to convert the building to a garage with factory space on the top floor. New steel girders and floor beams ensured the structure could support the weight of the automobiles. When the modifications were completed, the Superior Underwear Co. moved into the factory space. The firm employed 25 women to manufacture muslin underwear.

The New Taxicab & Auto Co. did not last. In 1913 Barzaghi remodeled the ground floor to commercial space for his new tenant, Rappaoport & Sacks, a stationery and cigar store. The second floor now became home to the Reeves’ Conservatory. An advertisement in 1916 noted, “Dancing taught correctly. Reliable, select, Established.” It added, “New Specialties—Ballroom, Classic, Stage.” The dance school would remain at least through 1920.

In 1928 Barzaghi leased the ground floor to the Bickford Lunch System. Bickford’s Restaurants were a mainstay of early to mid-20th Century New York. It all started in 1902 when Samuel L. Bickford opened his first restaurant. Within two decades he owned a chain offering quick food at affordable prices. In those pre-Depression days, the company described itself saying “The lunchrooms operated are of the self-service type and serve a limited bill of fare, which makes possible the maximum use of equipment and a rapid turnover. Emphasis is placed on serving meals of high quality at moderate cost.” Bickfords installed striking a new storefront completed with a striking row of Art Deco stained glass panels.

In 1928 Barzaghi leased the ground floor to the Bickford Lunch System.

The former dance studio became a meeting hall, home to the West Side Workers’ Club, a Socialist group. On the night of November 9, 1933, it hosted a lecture by Dr. Reuben Levins on “A Doctor’s Observation in the Soviet Union,” and on January 7, 1934, Jack Stachel led a discussion on “The Strike Wave and the N. R. A.” A less controversial group, the Knights of Columbus took over the space in 1935, followed by the Ancient Order of Hibernians in 1937.

In 1953 Bickford’s restaurant made way for the Paradise Food Store. By the early 1970’s the meeting space was home to the Puerto Rican Hispanic Sports Committee, Inc., and the former grocery store was the Nueva Princessa restaurant. One of the upper floors was home to the Carmel Limousine Service offices for more than a decade, starting around 1997. Carmel would be immortalized in their “just call six” commercial jingle.

Despite its many incarnations, the little building where well-to-do Upper West Siders once browsed for automobiles, retains much of its 1901 appearance.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses currently at 2642 Broadway: