The Metro (Midtown) Theatre

by Tom Miller

The seven-story Glenham Apartments opened at No. 2626 Broadway, between 99th and 100th Streets, in 1902. The sprawling apartments–seven and eight rooms each–were by no means inexpensive. They rented for between $800 to $1000 per year, equal to as much as $2,400 per month today.

The Great Depression may have dealt a significant blow to the building’s owners; or it may have simply been the changing neighborhood that brought about the end to the Glenham. It was demolished in November 1931. Brothers Arlington and Harvey Hall, partners in the A. C. & H. M. Realty Co. envisioned a motion picture theater on the site.

Both Russel M. Boak and Hyman F. Paris had worked in the drafting rooms of architect Emery Roth. They struck out as partners in 1927, forming the firm Boak & Paris. By now they were giving their own spin to the Art Deco style, most often in the form of apartment buildings. The firm was awarded the commission to design the theater (with the inexplicably misleading name ‘Midtown’) in 1932 and they filed plans that December.

With the arrival of the Great Depression the lavish motion picture palaces of the 1920s, with their pipe organs and cavernous lobbies, became a thing of the past. Boak & Paris produced a relatively intimate theater. What it lacked in the earlier grandeur it made up for in its sleek, streamlined design.

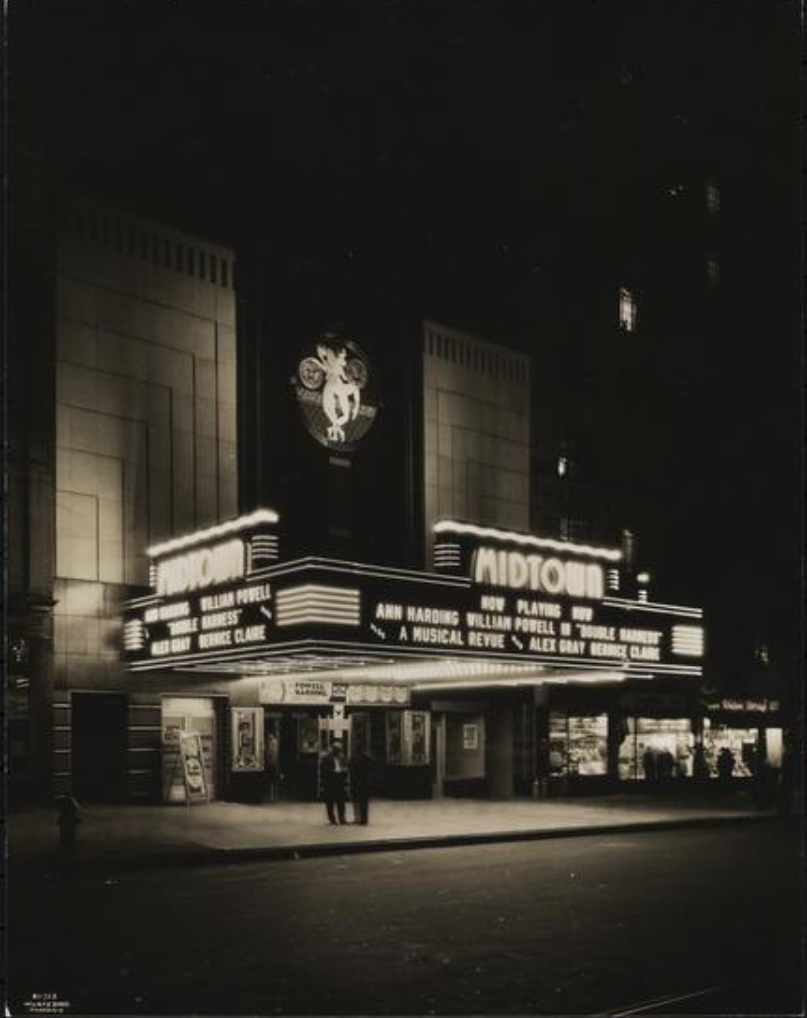

Completed on June 2, 1933, the theater was on the cutting edge of architectural trends. The black-and-silver stripes of the glazed terra cotta street level facade was echoed in the four chrome bands that girded the overhanging marquee. Boak & Paris used illumination as an element of the theater’s architecture, dramatically lighting the underside of the marquee, its lettering and decorations, and casting flood lights on the upper facade.

It was that upper facade that set the Midtown Theatre apart. The stair-stepping lines of the gray terra cotta on either side of the central section drew the eye to the large colorful medallion. Here two figures, one weeping and holding the Greek mask of Tragedy and the other dancing with the mask of Comedy, represented theater. The black terra cotta wall on which it appeared was trimmed in thin red lines and culminated in a wavy parapet and Empire State Building-like ziggurats.

Completed on June 2, 1933, the theater was on the cutting edge of architectural trends. The black-and-silver stripes of the glazed terra cotta street level facade was echoed in the four chrome bands that girded the overhanging marquee.

Depression Era Americans escaped the reality of everyday life at the movies. Here, for at least a while, they could forget the gloom outside the darkened theater while they watched upbeat Busby Berkeley musicals and Marx Brothers comedies. Upper West Side residents saw first-run motion pictures at the Midtown Theatre, no longer having to ride the subway to Times Square.

Even during the Depression many New Yorkers got away from the city in the summer. With a diminished clientele some motion picture theaters, like the Midtown, closed for the month of July. On August 9, 1938 The New York Times reported that the theater would be reopening that week, showing the comedy The Rage of Paris starring Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Danielle Darrieux, and the mystery There’s Always a Woman with Joan Blondell, Melvyn Douglas and Mary Astor.

Fred J. Dollinger was the manager of the Midtown Theatre in the early 1940s and he took his job very seriously. Among his duties was ensuring that motorists obeyed the no-parking rules directly in front of the theater so movie-goers could easily be dropped off or picked up.

And so when Alexander J. Mayer pulled up at the curbside around 6:20 on the night of September 10, 1942, the theater’s doorman pointed out that he could not park there. Mayer ignored the warning and went to a nearby restaurant. Dollinger decided to teach him a lesson on obeying the rules.

Mayer had been in the restaurant only a few minutes before a passerby, Louis Smith, came in and told him his left rear tire had been slashed. He pointed out Dollinger as the culprit.

In night court Dollinger insisted he had not committed the deed; but Mayer had brought along his witness. The following day The New York Times reported “The price of an automobile tire was $50 for Fred J. Dollinger, 60 years old, a motion picture theatre manager, last night, and he didn’t even get the tire.”

Motion picture theaters in general suffered a tremendous blow following the advent of television. Families that routinely went to the movies once or twice a week now stayed home. In the 1970s the Midtown Theatre, which for four decades had presented only first-class entertainment, became an adult film theater. It was rescued in 1982 when Daniel Talbot, owner of New Yorker Films, purchased it and spent $300,000 to renovate it as a specialized theater that screened vintage and foreign films. He renamed the 535-seat theater the Metro.

The Metro became known for its film festivals. In the summer of 1983 it offered a George Cukor festival that included the 1933 Dinner at Eight and the 1938 Holiday with Cary Grant, Katherine Hepburn and Lew Ayres.

The following spring the Metro was the site of the 10th “Perspectives on French Cinema” series. Five directors personally introduced their works and 11 new French films were screened. Among the films being premiered in America was 24-year old Caroline Roboh’s Clementine Tango. The program notes described the plot as being about “an aristocratic young man who discovers traces of his father’s past love affairs in a freakish Pigalle nightclub” and “a seductive but innocent adolescent girl enamored of tango dancing.”

Soon, however, the theater was renovated by Clearview Cinemas. By 1986 the auditorium had been sliced in half with one 325-seat “twin” theater on the lower section and 200 seats on the upper. Boak & Paris’s striking Art Deco interiors were still intact; although severed at the waist.

A terrifying incident occurred on May 9, 1999 when two armed men entered the theater around 10:30 at night. They ordered the concession stand employee to take them to the manager’s office. There they tied up both men and two other employees with duct tape before making off with around $2,000 in the day’s receipts.

The Metro closed in 2002. After two failed attempts to reopen, rumors spread that it would be replaced by a Gristedes grocery store. Then, happily, in November 2004 it reopened as an independent theater called the Embassy’s New Metro Twin. Similar to the first Metro incarnation, it screened foreign and independent films.

By 1986 the auditorium had been sliced in half with one 325-seat “twin” theater on the lower section and 200 seats on the upper. Boak & Paris’s striking Art Deco interiors were still intact; although severed at the waist.

But that venture, too, did not survive. In November 2005 the owner, Albert Bialek, gave up and padlocked the doors. He explained to reporter Alex Mindlin of The New York Times “As a neighborhood theater, the building is obsolete. It can’t compete with the bigger multiscreen houses.”

The Landmarks Preservation Commission gave Bialek permission to demolish Boak & Paris’s stunning interiors. He told Mindlin he considered “leasing the space to a dinner theater, a restaurant or a store.”

In the summer of 2008 a large FOR SALE sign covered the marquee. One option after another came and went, including proposals to renovate the space as an Urban Outfitters store and a home for an arts-education nonprofit. Then, in 2012 The Alamo Drafthouse seemed to have come to the rescue.

The Texas-based motion picture theater chain announced its intentions to open a New York branch. In a press release the company said “The Alamo Drafthouse at the Metro will provide food and drink service to your seat and will uphold its famously strict no-talking policy.” (That policy included a prohibition against cell phones.)

But the high hopes of preservationists and Upper West Siders were dashed in October the following year when Alamo Drafthouse Cinema’s website announced “too much has changed since we initially began work on the location.” After having spent almost $1 million on the project, CEO Tim League sighed “We were shovel-ready, but we didn’t lift the shovel…We’ve invested a lot of time and money into it.” The firm had made the decision that the spot was simply not “financially viable.”

When a lease was signed in 2015 with Planet Fitness, it was seen by many as, at least, a way of preserving the building. Councilman Mark D. Levine said “I think any tenant is better than abandonment. And while it is a chain, at least it isn’t a Duane Reade.” And Planet Fitness promised that it would respect the structure’s historic details in creating its gym.

But by spring of 2020, while the marquee still proclaims SPACE AVAILABLE and the Art Deco awaits its next potential future with rumors of a mutli-screen theatre-restaurant combination.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Landmarks Timeline

Keep Exploring

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 2626 Broadway:

Meet Toby Talbot!

Meet Gary Dennis!