The Garmont

by Tom Miller

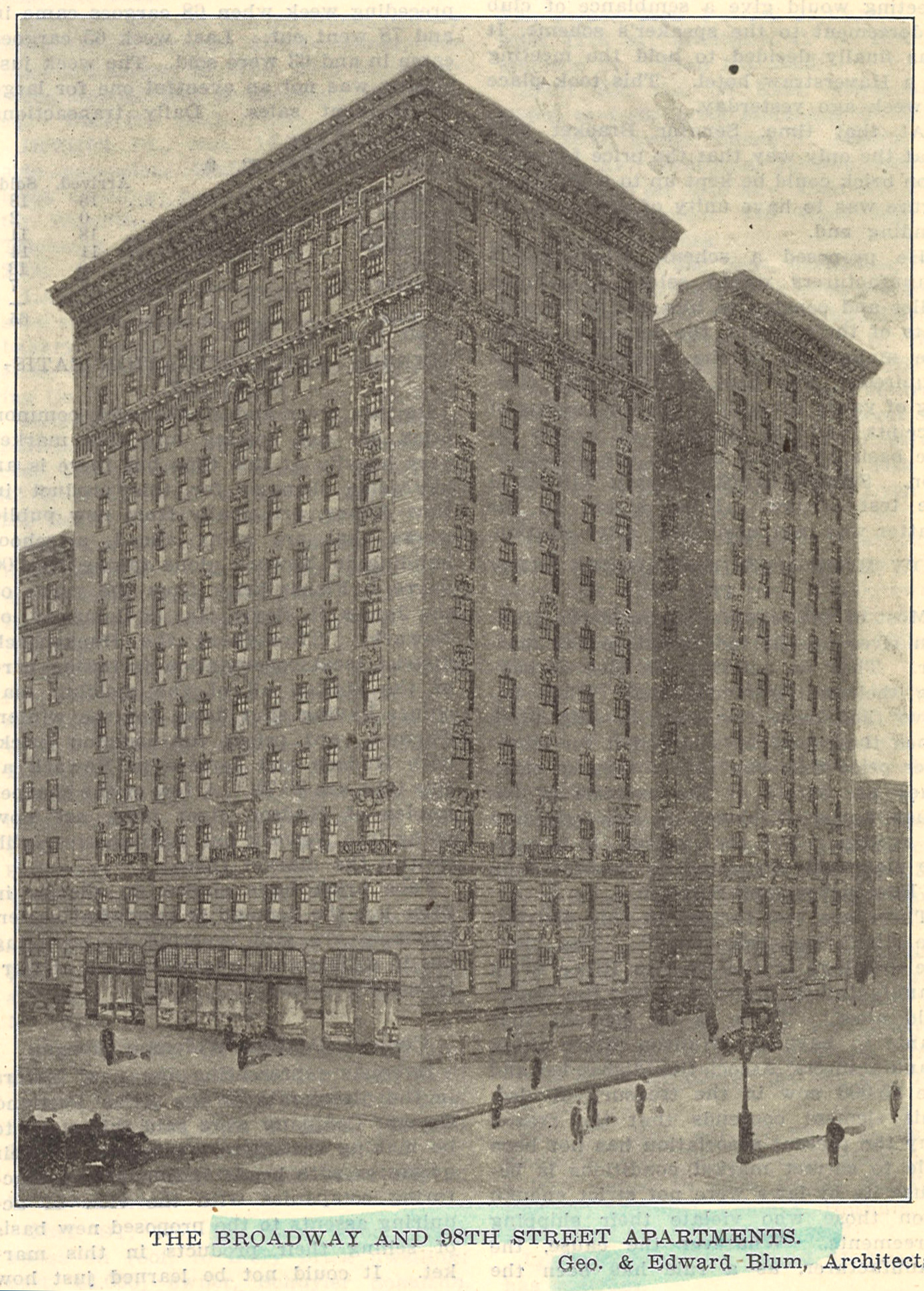

On January 22, 1910, the Real Estate Record & Guide reported that architects George and Edward Blum had been “commissioned to prepare plans for the improvement of the northeast corner of Broadway and 98th st., with a 12-story fire-proof apartment house,” by builders T. J. McLaughlin Sons. The cost of constructing the large building was placed at $350,000—roughly the equivalent of $11 million in 2023.

Called the Gramont, the upscale building was completed in 1911. Blum & Blum’s overall Renaissance Revival design was liberally sprinkled with Beaux Arts decorations—seen in the stone-and-iron balconies of the third floor and the frothy, carved spandrel panels. The architects tucked the entrance on West 98th Street between two deep wings that provided light and ventilation to the interior suites.

The names of the well-heeled residents appeared regularly in the society columns. Such was the case on April 7, 1912, when The New York Times reported, “Mrs. Norbert Bachman of 215 West Ninety-eighth Street will give the second in a series of musicals and sewing sessions in her home on Thursday of this week.” She held the events to benefit the East Side Clinic.

Like Mrs. Bachman, all socialites were expected to involve themselves in worthy causes. On March 16, 1913, the New York Herald reported that a few days earlier, “Mrs. Irving W. Bamberg and Miss Dorothea, of 215 West Ninety-eighth street, took a party of forty poor boys and girls from the west side settlements to see the performance at the Hippodrome. Each member of the party received a box of candy.”

The residents’ affluence made them tempting targets for thieves and scam artists. Civil War veteran J. T. Lackman and his family lived in the Gramont in 1914. Harry Campbell, known as the “Phoney Kid,” and his wife Hattie, alias “Chicago Annie,” were well-known to law enforcement at the time. Campbell had already served time in Sing Sing Prison, as well as in Capetown, South Africa, and in Glasgow, Scotland. Somehow he discovered that the Lackmans had a line of credit with the Lord & Taylor department store.

On May 13, 1914, Campbell walked into Lord & Taylor, identified himself as J. T. Lackman, and ordered a diamond brooch with a price tag of $135. He asked that it be sent by messenger to the Lackman apartment and charged to his account. Then, the next day he returned, complaining that the jewelry had never arrived. The messenger was summoned, who insisted he had delivered the package.

The residents’ affluence made them tempting targets for thieves and scam artists.

The Evening World reported that Campbell replied, “All right, come up to the house with me, and we’ll straighten this out if there has been a mistake.” He and the messenger went uptown to the Gramont. “As they reached the house, the man instructed the messenger to wait outside while he went in and prepared for the visit.”

While the boy waited on the sidewalk, Campbell went up to the Lackman apartment, where he identified himself as an employee of Lord & Taylor, explained there had been a mix-up in addresses, and asked for the brooch back. Mrs. Lackman handed over the package, Campbell told the messenger that the pin had indeed been delivered, and everyone went on their way. It was not until the bill came that the crime was discovered. Five months later, on October 5, Mrs. Lackman and her daughter were called to Police Headquarters where they identified Campbell as the man who had received the brooch.

Living here in 1917 was Sarah M. Stiassny, described by The New York Times as “a wealthy widow,” her maid Dora Watts, and her nephew Richard Isaac Epstein. Epstei managed Mrs. Stiassny’s business affairs, which included a large amount of Manhattan real estate. The capacious apartment would become the scene of a puzzling murder mystery that year.

On November 7, 1917, Epstein walked into his aunt’s bedroom to find her dead, with a bullet wound in the temple. The New York Times reported, “A revolver lay close to the woman’s hand, and on a table was a note suggesting suicide.” When the police arrived, Epstein was “hysterical” with grief. He told them, “She probably committed suicide in dread of his being drafted.”

But the scene quickly raised questions. When the body was examined more closely, a second wound was found on the elderly woman’s side. Only one spent shell was found in the chamber of the revolver (the second was later found in the drain trap in the kitchen), and Mrs. Stiassny’s kimono, with the blood from the bullet to her torso, was discovered hidden under the wooden cover of a radiator. Moreover, a handwriting expert later concluded that the suicide note had not been written by Sarah Stiassny.

The investigation went on for weeks. Epstein had the most obvious motive in the murder. His aunt’s will, executed in May 1914, left him just $5,000 “and a few minor household effects.” But a subsequent will, made four months before the crime, left him the bulk of her estate, estimated to be about $5.7 million by 2023 terms. As reported by The Sun, a saloon keeper named Alberito, told the district attorney “that young Epstein went to him early in the summer with a pistol that he wanted repaired.” And on November 12, the newspaper began an article saying, “A statement that Mrs. Sarah M. Stiassny of 215 West Ninety-eighth street had quarreled with Isaac Epstein, the 24-year-old cousin [sic] who lived with her, on the night before her body was found in her bedroom with two bullet wounds in it was the outstanding feature of the case yesterday following an examination of half a dozen witnesses by Assistant District Attorney Dooling.”

Sarah’s relatives were quick to file objections to the filing of the will for probate. On November 20, the New York Herald explained, “there will be a contest over the will she left.” And, yet, rather astonishingly, no one was ever convicted of Sarah Stiassny’s murder, and Richard Isaac Epstein inherited her sizable estate.

Another well-heeled family living in the Gramont was that of Herbert Leigh Borden. He was born in 1863 in Goldsboro, North Carolina, and had been associated with the railroad industry since 1887. He was the vice president, secretary, assistant treasurer, and a director of the Atlantic Coast Line. He and his wife, the former Mary Mead Maffitt, had a daughter, Mary. When The Sun reported on her engagement to Kenneth Neiman Chambers on December 28, 1919, it noted, “Miss Borden is a granddaughter of the late Capt. John Newland Maffitt of the Confederate Army.”

The wedding occurred on January 22, 1920, in the Crystal Room of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. The “reception and ball” was to be held in the ballroom, after which dinner would be served. But there was a glitch. The New York Times reported, “when the guests started to enter the ballroom, they found it filled with smoke and firemen busy seeking out the flames.” Those flames were from a fire that had started in the hotel during the wedding ceremony. The formally dressed guests seem to have taken it in stride. “The guests left the ballroom calmly. The rescue squad extinguished the fire after an hour’s work and the dinner was continued,” said the article.

Despite the wrinkle, The Sun called the wedding “one of the most brilliant of the season.” It noted, “On their return from their honeymoon in Los Angeles and Southern California, Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth N. Chambers will live at 215 West Ninety-eighth street.” (It is unclear whether they rented a separate apartment or moved in with the Bordens.) The “brilliant” ceremony did not guarantee a brilliant marriage. Six years later, in December 1926, the wedding was annulled, and Mary married Aubrey Campbell Jay-Smith three months later.

Perhaps more scandalous was the incident involving John S. Sutphen Jr., and his wife, the former Adelaide Hedden Reynolds. A graduate of Princeton University, Sutphen had grown up in his parents’ lavish mansion at 311 West 72nd Street. He was now a vice president of Ridley’s Confectioners. The couple had married in May 1916.

“The fellow jumped out of a telephone booth without warning” and landed a punch to Adrian’s face.

John and Adelaide Sutphen summered in Allenhurst, New Jersey. They invited a friend, Adrian Arthur, to be their weekend house guest in August 1921. The trio attended the annual masquerade ball at the Allenhurst Hotel on Saturday night, August 27. The New York Times noted it “caps the social climax for the fashionable beach colony.” Adelaide and Adrian were dancing, when a young Cuban man, Salvadore Laborde, attempted to cut in. The Cornell University junior made the excuse of saying he thought he knew Adelaide. The New York Times reported they “both informed him of his mistake.”

Undaunted, after a few minutes, Laborde returned. Adelaide “repulsed him,” and “Arthur seconded her sternly.” But, according to witnesses, Laborde’s conduct became even more objectionable. The incident seemed to be over until Adelaide and Adrian went downstairs to the grill room for refreshments. Laborde was there and, according to Adelaide’s testimony later, “The fellow jumped out of a telephone booth without warning” and landed a punch to Adrian’s face. Adrian fell backwards, striking his head on the concrete floor. He died from a skull fracture. Adelaide became the key witness in Salvadore Laborde’s murder trial.

An erudite couple living here in by the 1960s were Ephraim and Mary Hochlerner Cross, whose summer home was in Greenport, Long Island. Ephraim Cross graduated from City College in 1913, received his master’s degree from Columbia University in 1914, and his doctorate from Columbia in 1930. He also held a law degree from New York University. He joined the staff of City College in 1931 as a professor of Romance languages, a position he retained until his retirement in 1963.

After graduating from Hunter College in 1912, Mary Hochlerner Cross became a public school teacher. As her career developed, she specialized in teaching physically handicapped children. In 1975 she traveled to Piestany, Czechoslovakia for medical treatment. Unfortunately, the 82-year-old never returned to the couple’s apartment. She died there on July 5. Dr. Ephraim Cross remained in the apartment alone. He died of cancer on January 15, 1978, at the age of 84.

While many of the early 20th-century apartment buildings on the Upper West Side declined in the latter part of the century, the Gramont did not. When it was converted to coops in 1986, there were still just six apartments per floor.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2600-2610 Broadway:

Meet Anjie Cho!