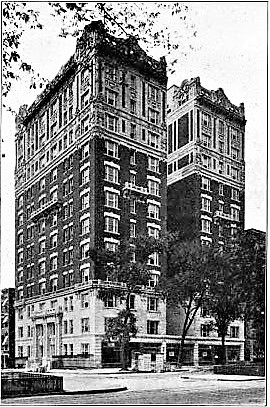

The Cornwall

by Tom Miller

French-inspired apartment buildings had begun rising on the Upper West Side since 1899 when millionaire William Earl Dodge Stokes began his massive Ansonia on Broadway between 73rd and 74th Street. If was followed rapid-fire by mighty apartments like the 1901 Chatham Court on Central Park West, and the 1903 Belleclaire at 77th Street and Broadway.

Their architects, for the most part, followed the lead of upscale Paris hotels in designing the frothy brick and stone confections. The sprawling apartments were intended to provide all the comforts of a private home. On September 15, 1901 the New-York Tribune noted “Since the introduction in this country of the ‘French flat’ system, the improvements have been of a nature that removes the ‘American apartment house’ to a sphere far beyond anything that France has known. Year by year the luxury increases, until the apartments now building are veritable palaces. Indeed, they have comforts and conveniences that few European palaces can boast.”

In 1909 Arlington C. and Harvey M. Hall began construction on another one, at the corner of West 90th Street and Broadway. The brothers got their affinity for building and real estate development honestly. Their extended family had been house builders and sash makers, and their cousins William W. and Thomas M. Hall were extremely well known developers of high-end homes under the firm name Hall & Hall. But while Hall & Hall still constructed speculative, upscale private homes at the turn of the last century, Arlington and Harvey turned their focus to theaters and apartment houses.

They hired the well-known architectural team of Neville & Bagge for this project, and the results were far different from any of the existing apartment buildings to date.

Completed the following year, the eight-story Cornwall is faced in red brick and trimmed in limestone. At first glance it seems to be yet another Beaux Arts apartment hotel with occasional stone balconies clinging to the facade and ornate carved stone and terra cotta decorations. But closer inspection reveals that the architects had turned to Art Nouveau for the ornamentation.

The sinuous, sexy style had swept Europe as early as 1890. And while it became highly popular with New York City designers for jewelry and household items like silverware and leaded glass lamps; it rarely appeared in architectural form in Manhattan.

But the Cornwall overflowed with lusty Art Nouveau motifs–anthemion forms above the 10th floor openings lost their traditional rigidity and took on swirling Art Nouveau personalities, for instance. But the pièce de résistance was the sensational terra cotta cornice/pediment. Two stories tall at its highest points, its corner and central sections on the Broadway elevation erupt in intertwining vines that form open screens of budding flowers.

Neville & Bagge gave the Cornwall a U-shaped plan which provided light and air while eliminating the often-ugly interior light shafts of a square-O plan. Architects’ and Builders’ Magazine called it a “street-opening court” and noted it gave “a more pleasing prospect for the apartment dweller…Aside from the mere aesthetic value of having the court interior finished architecturally in keeping with the main facade, there is the real value present of having the interior court artistically treated and presenting a more or less pleasant outlook.”

The architects placed the entrance on West 90th Street. The arrangement afforded some privacy to the moneyed residence as they came and went, but also provided income-producing retail spaces on Broadway.

Apartments in the Cornwall ranged from seven to nine rooms, and included two to three bathrooms. The accommodations were swanky enough that both Arlington C. Hall and Harvey M. Hall reserved apartments for their families.

Neville & Bagge gave the Cornwall a U-shaped plan which provided light and air while eliminating the often-ugly interior light shafts of a square-O plan.

Among the initial tenants was William Irving Twombly and his family. A Maine native, he had been inventing new modes of transportation for over a decade. In 1894, for instance, the New-York Tribune reported he “recently built a bicycle to be propelled by the vapor of ether [and] has now finished an ether launch, operated in a similar manner by mechanism in which the vapor of ether take the place of steam.”

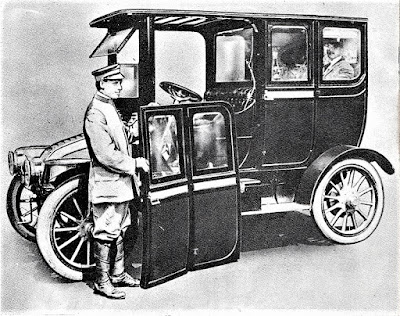

By now he ran the Twombly Motors Co., manufacturing automobiles. Twombly’s cars, which exhibited his sometimes quirky touches, sold to upper class customers.

The Twombly household consisted of his wife, Ethel (known as Minnie) whom he had married in their hometown of Portland in 1896, their son Glendon Irving and daughter Hallie. While her husband ran his car company and invented new improvements, Minnie was involved in political and social issues. She was the Treasurer of the New York Legislative League, a member of the Society for Political Study and of Mrs. Mackay’s Equal Suffrage Club, and wrote lectures on the “Prenatal Culture.”

In 1912, Twombly patented two new inventions, an internal combustion engine and a flexible metallic casing with an inflatable inner tube. Glen was 16 years old that year and enjoyed the benefits of his father’s business by owning his own motorcycle.

He was riding along West End Avenue on May 2 when, at 92nd Street, “he ran against Miss Josephine Ulf, who was standing in the middle of the block looking at a clock,” according to The Sun. Both Glen and the girl were hurt.

The following morning his father accompanied him to police court where Twombly promised to pay the cost of Josephine’s medical bills. He paid Glen’s $5 fine for speeding and they went home.

Then suddenly on June 22, nearly two months after the incident, police arrived at the Cornwall apartments and took the teen away. He was held overnight on $500 bail and committed to appear in court on October 17.

Glen’s surprise arrest came on a complaint from lawyer Abraham S. Gilbert who claimed, according to The Sun, “that Miss Ulf was governess in his family and that she was crossing the street with his two children when she was struck by the motorcycle. He asserted that the machine was going at the rate of thirty miles an hour and the young woman was nearly killed.”

Gilbert presented an eye witness, Edward E. Read. But it appeared to William Twombly that his son was being set up and Gilbert was after a financial settlement. Glen testified that he had never seen Read until that morning in court. Gilbert demanded that Twombly pay medical expenses of $315–more than $7,000 today–which he claimed he paid out of his own pocket.

The charges against Glen were dismissed (the judge found he had not intended to injure the girl). And then all parties would appear in court again on October 28 after Glen, with his father representing him as legal guardian, sued both Gilbert and Read alleging “malicious prosecution.” The suit charged Gilbert had had him arrested “as a means of compelling payments of money” from his father, and that Read “took part in the prosecution through malice and that both defendants had sufficient proof that he was not guilty.”

Nevertheless, it appears that Twombly was not happy with his son’s speeding. On his 18th birthday he gave Glen a new car, warning him to drive very carefully and that this time he would not bail him out if he got into trouble. But he did get into trouble.

On Friday night, September 12, 1913 he was speeding up Broadway when he was noticed by a motorcycle cop at 72nd Street. Patrolman Cohsenhirt estimated his speed at 30 miles per hour. Seeing the policeman behind him and knowing he would be in serious trouble at home, Glen stepped on the gas.

The New York Times reported two days later “The policeman told Magistrate Marsh of an exciting chase of several blocks on Broadway.” Glen was finally pulled over. He told the judge “I haven’t got the money, and there’s no use in asking dad.” Magistrate Marsh explained that he had to find the boy guilty and, if he could not pay the fine he would have to be jailed for a day. The New York Times reported “He chose the latter punishment, and went to a cell until 4 o’clock in the afternoon, when the prison day ends under the law.”

Eventually, the Twombly marriage would fall apart after William developed a wandering eye. A Michigan newspaper, the Ludington Daily News ran the headline on July 19, 1933 “Prominent Inventor Again Put In Jail On Charges of Wife” and reminded readers that the couple had separated in 1925. She accused him of having “his face ‘lifted’ and his hair dyed so he could ‘step out.'” By now she had had him arrested several times for adultery and desertion. Calling him a “once nationally-known inventor,” the newspaper said Minnie was “really destitute” and that William refused to pay support.

Another early resident of the Cornwall was Melvina Hammerstein, the wife of impresario Oscar Hammerstein. She was his second wife, and they had not lived together for several years when, in June 1911 she obtained a divorce. She was suffering from heart disease at the time, and on January 9, 1912 she died in her apartment.

According to the New-York Tribune, “with her when she died were her two daughters.” On January 11 that newspaper reported “The funeral of Mrs. Hammerstein will be held in her apartments this evening.” Oscar Hammerstein would not be attending. The morning after hearing of Melvina’s death, he boarded the Lusitania for Europe. The Tribune explained “Important business called Mr. Hammerstein to London.”

In the meantime, domestic relations were not going so well for another family in the Cornwall. Charles Mason Hall was a wealthy insurance broker, a member of the Exton-Hall Brokerage firm on Wall Street. He owned race horses and the 40-foot yacht, the Caress. He and his wife, the former Ella Louise True, had a son, and three daughters. But when he moved them into a sixth floor apartment in the new building, he did not join them. Ella explained later that he had an “infatuation for another woman.”

Nevertheless Hall supported his family whose comfortable lifestyle included a live-in maid. Not long after moving into the Cornwall, the Halls’ eldest daughter married. But tragedy occurred in the fall of 1912. Their 15-year old son, Alexander Hadden Hall owed his own automobile. On November 9 he drove his sister to Hazlet, New Jersey to visit family friends, the Stevensons, for the weekend.

The next day Alexander and James H. Stevenson, also 15 years old, headed out to go duck hunting.

Alexander pulled his car up to the railroad tracks near the Hazlet station. The guard bars were down and he waited as a freight train passed. When the bars rose, he drove onto the tracks. According to The New York Times, “He had just reached the track when a train going at a rate of fifty miles an hour crashed into the automobile.” The 70-year old flagman responsible for raising and lowering the gate had not noticed the approaching train.

Both teens were hurled from the automobile and killed. Alexander’s funeral was held in the Cornwall apartment.

Now Ella lived on in the apartment with 13-year old Sybil and 9-year old Lucy. She tried repeatedly to “cure her husband” of his affection for Emma S. Smith, with no success. She went so far as to sue Emma “to restrain her from further alienating the affections of Mr. Hall,” explained a newspaper. It was a nearly unique move. There was only one precedent, in Texas, in which the outside party was sued to stop “paying attention” to a spouse.

It was an emotional strain that affected Sybil as well. On September 22, 1913 The Sun reported that both she and her mother were “convalescing from a recent illness,” and The New York Times said “Both appeared to be greatly wrought up over their experience.”

When Charles showed up at the apartment on Sunday night, September 21 regarding business, Ella was determined not to let him go. Lieutenant Hayes of the West 100th Street Station received a telephone call from Hall asking for a policeman to come to the Cornwall. He said he was being held prisoner by his wife.

[Ella] tried repeatedly to “cure her husband” of his affection for Emma S. Smith, with no success. She went so far as to sue Emma “to restrain her from further alienating the affections of Mr. Hall,” explained a newspaper. It was a nearly unique move. There was only one precedent, in Texas, in which the outside party was sued to stop “paying attention” to a spouse.

The hallboy took Patrolman Peter Conlin to the Hall apartment. Ella, sobbing on the other side of the door, said he was not wanted. Charles, meanwhile, could be heard shouting “Let him in at once.”

The maid admitted the officer, who was met with a strange scene. Hall was seated in a chair, while Ella and the two girls were crying hysterically.

“Get me out of here. I am being restrained here against my will,” cried Hall.

Ella pleaded “No, no, officer. He is my husband, and we love him. I will not let him go.”

While Conlin tactfully explained to Ella that he could not force her husband to stay, “Mr. Hall walked out of the apartment and went on his way,” said The Sun.

Hall told a reporter from that newspaper that he had not visited the apartment in five years. One can assume that he did not return.

Like the Hall and Twombly boys, the son of Arlington C. Hall had his own automobile. When the family went to the newly-opened Claremont movie theater on Broadway at 135th Street on November 15, 1914, for some reason they took two cars. Paul exited the theater first, just in time to see six men driving his father’s car away.

According to The New York Times the following day, “Paul Hall jumped into his own machine with his father’s chauffeur, Frank Watson, and gave chase.” Hall and Watson sped down Broadway at 45 miles per hour in close pursuit of the thieves. They stopped at West 102nd Street to pick up Policeman Sewell. As they sped down the thoroughfare, Sewell pulled out his revolver and “started shooting at the tires of the car ahead.”

The car thieves headed to Fifth Avenue and started north again. Alerted by the commotion, Policeman McDonald began firing his weapon at 110th Street and Fifth Avenue. He got off six shots, and exploded a tire. The crooks then turned their own weapons on McDonald, one bullet tearing through his coat.

“At 120th Street the stolen car slowed down and three men jumped out, taking two new tires with them, and at 121st Street it stopped and the other three men were arrested,” reported The New York Times.

The Cornwall continued to be home to socially recognized families, including Dr. Victor Frederickson and his wife. They remained in the building into the 1920s and Mrs. Frederickson’s name routinely appeared in society columns as a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and as president of the Wisconsin Women’s Society.

While many of the grand turn of the century apartment buildings suffered decline and abuse during the Depression years and after; the Cornwall managed to survive serious humiliation. Even the floorplans remained intact. (The Government did pay attention to the voting habits of some of its residents, however, publishing the name of Ephraim Kahn as a Communist Party supporter in 1936, for instance.)

The sometimes startling preservation of the building was evidenced when, in 2013, John Ziegler moved out of the ninth floor apartment he had occupied since 1978. The four-bedroom space was purchased by president and CEO of New York Times Company, Mark Thompson and his wife, writer Jane Blumberg.

In reporting the sale, New York Times columnist Mark Maurer noted the apartment had “four sets of French doors, a nonfunctioning gas fireplace and stained glass windows.”

The remarkable state of preservation, however, is not guaranteed since the Cornwall is not a designated landmark structure. A rare example of Art Nouveau Manhattan architecture, it is a gem worthy of that landmark status.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

building database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses currently at 255 West 90th Street:

Meet Jamaluddin Azin (Ran)!