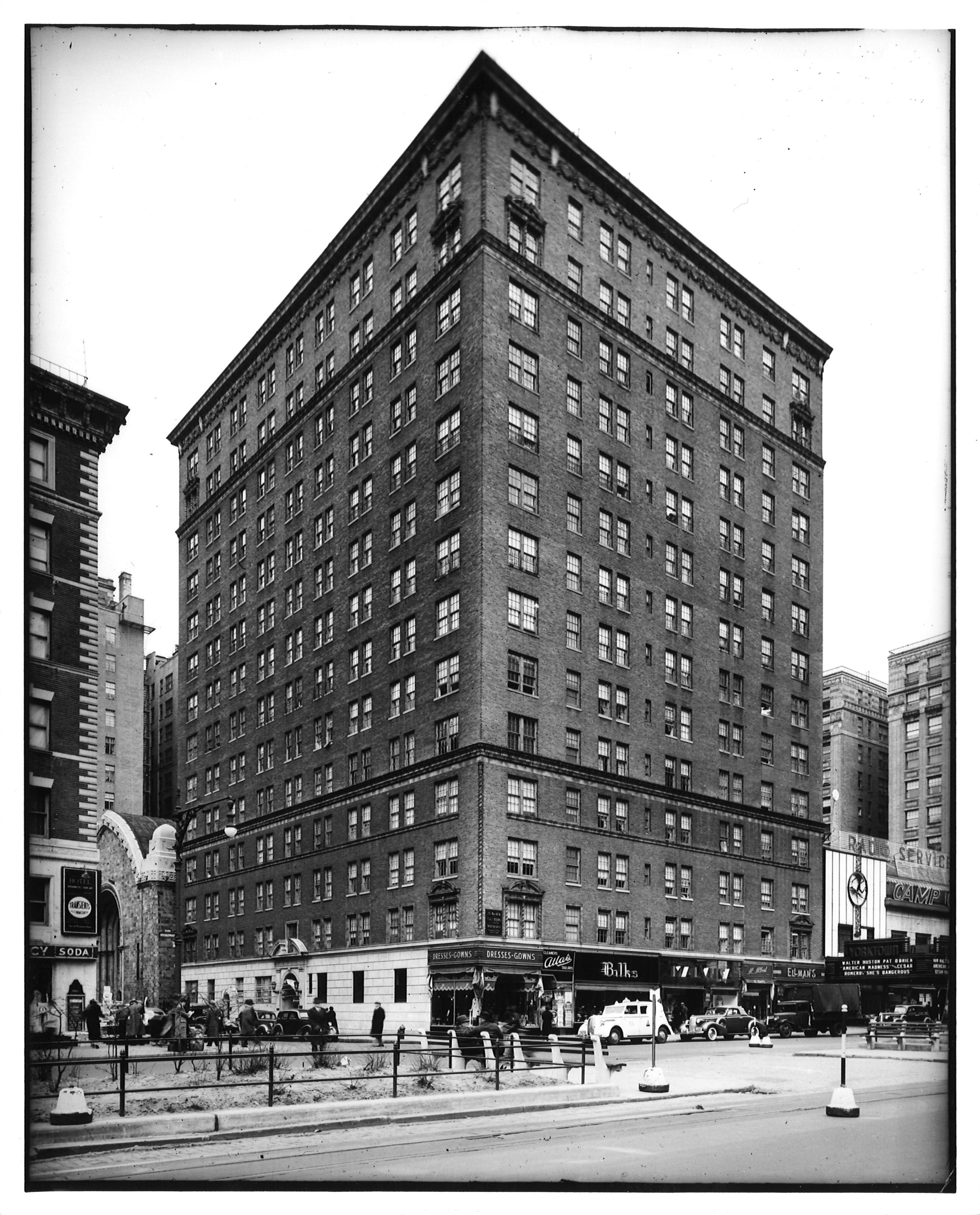

255 West 88th Street

by Tom Miller

On January 31, 1923, The New York Times reported that Joseph Golding had purchased the two three-story houses at 253 and 255 West 88th Street. The article noted that he had recently purchased the abutting structure at the northwest corner of Broadway and said “he contemplates improving [the property] with a fourteen-story apartment house with stores along Broadway.”

Golding was the principal in the Golding Construction Co. He demolished the vintage buildings and hired the architectural firm of Rouse & Goldstone to design a modern apartment building on the site. Completed in 1924, the 14-story Renaissance Revival style structure was faced in variegated brick and trimmed in terra cotta. It featured romantic touches like twisted columns, and elaborate Florentine window surrounds at the second floor. A terra cotta garland interrupted by occasional Renaissance shields ran below the otherwise unadorned cornice.

Apartments ranged from 5 to 7 rooms, with two or three baths. An advertisement touted “each master bedroom has a private bath. Rooms of unusual large size. Extra high ceilings. Dining room in each apartment.”

The financially comfortable tenants routinely appeared in the society columns. Such was the case on February 13, 1925, when The American Hebrew announced, “Mr. and Mrs. Emil S. Stern, of 255 West Eighty-eighth street, New York, gave a dinner dance last week at the Ambassador, for their debutante daughter, Miss Francisca Stern. There were more than a hundred guests at the party.”

Valez was working in apartment 8-F when the flammable materials he was using burst into flames.

Typical of the residents at the time were Vernon C. Gray and his second wife, the former Bertha Stimson. The couple was married in 1921. Born in Greenfield, Ohio in 1862, Gray was now a vice-president of the American Maize Products Company, vice-president of the Royal Baking Powder Company, and vice-president of the Royal Distributing Company.

The building was the scene of a horrific accident on November 1, 1927. Puerto Rican-born Joseph Valez worked for the building’s managing firm, Shirrford Realty Corp., as a “painter and floor scraper.” He was sent in when apartments became vacant to ready them for the next tenant. The young man was paid $20.77 per week, or about $325.00 in 2023 terms.

On that day, Valez was working in apartment 8-F when the flammable materials he was using burst into flames. He was burned over two-thirds of his body and went into cardiac failure. His death was deemed “naturally and unavoidably the result of the accidental injuries he sustained.” The Shirrford Realty Corp.’s insurance carrier refused to pay his wife, Josefa when an investigation revealed they had never been formally married. After a court battle, the widow received $6.23 per week “during widowhood.”

In 1934 two of the apartments were combined into a luxury suite. An advertisement described the nine-room apartment as having four bathrooms and four bedrooms, adding “Unusual layout. Extra large rooms, 12 spacious aired closets, gold-plated bathroom fixtures.”

The following year, at around 8:00 on the night of December 7, 1935, a fire broke out in the basement. The doorman sent word to the 60 families, many of whom were having dinner, that there was no danger. But the smoke from the blaze soon proved him wrong. The New York Times reported, “However, the smoke shortly was carried through the halls and into the apartments, forcing men, women and children to make a hasty dash to the street.”

A second alarm was called in. The article said, “While several hundred spectators, held in check by the police, looked on, the firemen fought a spectacular fight underground to gain control of the blaze.” Four hours after they arrived, fire fighters had won the battle, but five had been overcome by smoke and eleven others injured.

Four years later tenants were again routed by smoke. On January 24, 1939, a three-alarm fire swept through a two-story business building on the opposite corner, at Broadway and 89th Street. The New York Sun reported, “More than forty families fled from their homes in the apartment house at 255 West Eighty-eighth street as a heavy smoke screen enveloped the neighborhood.”

Not all of the residents were law-abiding citizens. Matthew and Nathan Frank, presumably brothers, lived here in 1945. The 62-year-old Matthew Frank listed his profession as “market trader,” but his actual income seems to have come from a more lucrative source. On November 26 that year he and five other men were arrested for running a gambling place. The head of the ring was Romeo Yellozzi, whom The Herald Statesman said was “described by police as a ‘bookie big shot’ and a key man in bookmaking operations in the city.”

The elder Frank’s arrest did not prompt Nathan to change his ways. On February 20, 1951, The Kingston Daily Freeman reported that he and two women were arrested and charged “with operating a wire room.” (“Wire rooms” were gambling rooms where bets were made on horse races by telephone.)

As [Robert] Kennedy and his entourage passed 88th Street and Broadway, a resident tossed a firecracker out the window.

One resident in 1964 may have been overly excited at the prospect of seeing Robert Kennedy, the Democratic candidate for Senate, or simply foolish. The politician’s staff had announced that his motorcade would stop for “a walking tour along Broadway from 90th Street to 86th Street,” according to The New York Times. The article noted, “Actually, it was more of a shoving tour, as a cordon of policemen attempted to protect him from the crowds.”

As Kennedy and his entourage passed 88th Street and Broadway, a resident tossed a firecracker out the window. Expectedly, the noise triggered an immediate response. The New York Times reported, “At the sound of the explosion the police immediately closed in on Mr. Kennedy.” The perpetrator of the prank was not caught.

Living here in the 1970’s was Ben Zwerling and his wife, the former Sandra Chusid. Zwerling was a graduate of the University of Michigan and had been managing editor of International Automobile Magazine and a public relations executive before becoming part of the Kennedy Administration as the Director of Information of the United States Business and Defense Administration. He later was a syndicated columnist on foreign trade for the North American Newspaper Alliance.

Rouse & Goldstone’s substantial structure survives nearly unchanged a century after it was begun.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 2401 Broadway:

Meet Rachel Gavrieli!

Coming Soon!