The Symphony Theatre — 2527-2537 Broadway

by Tom Miller

On June 20, 1914, the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that the architectural firm of Tracy & Swartwout had filed plans for John Jacob Astor for a “two-story fireproof moving picture theatre, dance hall and restaurant” at the southwest corner of Broadway and 95th Street. Astor would soon change course regarding the building’s purpose.

Astor was appointed to sit on Mayor John Purroy Mitchel’s “market commission.” The Sun reported that “while inspecting and investigating markets,” in that capacity, he “was surprised at what he saw and concluded that the matter of handling and caring for foodstuffs should be improved.” He decided to build a “model market” to set the standard. The article said, “he had a message to carry to New York and he told it to Evarts Tracy of Tracy & Swartwout, his architects, and Mr. Tracy put it on paper and builders did the rest.” Astor’s two-story building, already under construction, was revamped as the Astor Market.

The Astor Market opened in October 1915. The Sun said, “The architect has designed the exterior in the style of the Renaissance Markets of Florence. The material is travertine, and a sgraffito frieze in rich color ornaments the entire cornice of 290 feet.” The frieze, designed by mural artist William A. Mackey, depicted vegetables, fish, poultry, fruit, and meats on the Broadway side, and “the evolution of market carriers” on the 95th Street side— “from the earliest boats to the modern motor truck.”

The interiors were designed for cleanliness, with white tile floors, “white Carrara glass counters,” and enameled ice boxes. The Sun said, “There are no concealed spaces, no mouldings to catch dirt.” Two 20-ton ice machines cooled the display cases and freezer rooms and made five tons of ice per day. An incinerator that reached temperatures of 1,700 degrees eliminated waste, garbage, and odors. Stressing the sanitary environment, Evarts Tracy told a reporter from the New-York Tribune “a fly would starve in this market.”

Unfortunately for Astor, the market, which had cost him $200,000 to build (more than 5.5 million in 2023 dollars), quickly failed. On April 18, 1917, The Sun reported that restauranteur Thomas Healy had purchased the building. “Mr. Healy has no use for a market and will remove it eventually,” said the article.

Evarts Tracy told a reporter from the New-York Tribune “a fly would starve in this market.”

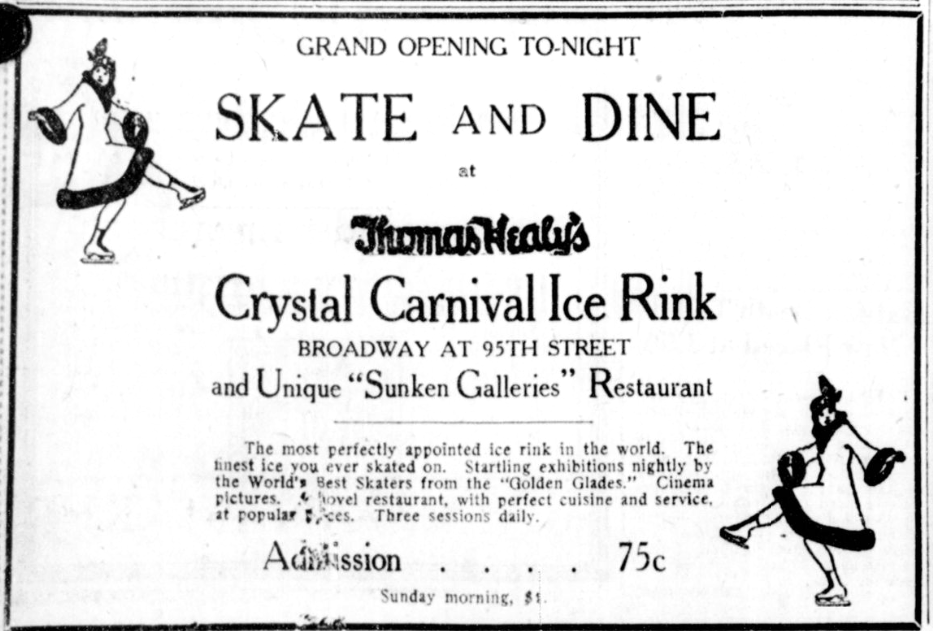

And indeed, he did not. Making use of the massive ice machines below grade, Healy transformed the ground floor into the Crystal Carnival Ice Rink. The basement became the Sunken Galleries restaurant. The venues opened on Christmas Eve 1917; an advertisement calling the Crystal Carnival “The most perfectly appointed ice rink in the world” and said the restaurant had “perfect cuisine and service.” Variety described “what promises to be unique in cabarets” saying, “The ‘Sunken Galleries’ restaurant occupies the lower floor and consists of four levels around a central amphitheater and is appropriately decorated.” The article noted that every afternoon and evening there would be “special skating entertainments by the ice artists now appearing at Healy’s Golden Glades.”

But that idea did not last, either. On March 23, 1918, the Record & Guide reported that Healy had leased the building to the newly formed Kennedy Theatres, Inc. (of which Healy was, not coincidentally, treasurer). “It will be remodeled, from plans by William J. Massarene, into a theatre primarily for the convenience of the restaurant of Thomas Healy,” said the article. “It will be known as the Symphony Theatre and will open about May 1.” Possibly as a cost savings measure, Massarene reused the configuration of the ice rink. “It will have no balcony or gallery. Seating arrangements for about 1,200 have been provided on the main floor, and also a mezzanine tier of boxes to accommodate about 300 people.”

The May 1st opening was, as it turned out, slightly ambitious. An unforeseen snag came when William Fox, who built the Riviera and Riverside Theaters one block to the north a few years earlier, sued to prevent the Symphony Theatre’s opening. His filing said in part, “William Fox contends that there are too many theatres in the upper Broadway section at present, and that the 1200 seating house that A. M. Kennedy intends opening on the Healy property would hurt all the others.”

Fox lost his battle, and the Symphony Theatre opened on June 14, 1918. The Dramatic Mirror reported, “Entering the Symphony will strike the average movie fan as an unusual process, wholly different from any other theater in town.” That was because when the patron entered the auditorium from the lobby, he was facing the back, with the stage and screen behind him. The critic felt that the configuration “is rather beautiful. The long side foyer is lighted by soft lights, and the curiosity is stimulated as one makes for the aisle entrance.”

Silent films required musical accompaniment, and the Symphony Theatre not only had a Kramer pipe organ, but a 50-piece orchestra. The Dramatic Mirror also applauded the stage, which ran the full width of the orchestra. Live vaudeville acts almost always shared the bill with films at the time. The article opined, “Having such a stage, the Symphony ought to be able to produce some very attractive tableaux and dance numbers, to say nothing of excellent scenic effects by lighting from the rear.”

The New-York Tribune reminded its readers of the building’s history. “The new theatre used, not so long ago, to be a market, owned by Vincent Astor, and later it was a skating rink. This accounts for its peculiar construction, which is quite unlike any of the contemporaneous movie palaces.” Peculiar or not, the newspaper’s critic approved. “Both in the construction and in the decorations it is a work of art.”

Kennedy devised a clever marketing scheme to attract the feminine crowd. On June 30, 1918, the New-York Tribune reported, “As a courtesy to the women patrons of the Symphony Theatre, the management announces that tea will be served every afternoon in the ladies’ rest room from 2 until 5 p.m. without charge.”

Unfortunately, this idea did not work, either. On April 21, just two months after the Symphony Theatre opened, The New York Clipper reported that the venue, which was intended “to give uptown New York the same class of entertainment as is furnished at the Strand, Rivoli and Rialto theatres, closed its doors last night.” The article said, “The career of the Symphony was a short-lived and stormy one.” Thomas Healy, who (despite being treasurer of the theater firm) was owed $21,000 in rent, was actively looking for a new proprietor for the space. Happily, for him, the theater was leased and back in operation by October. With the country mired in war, it screened patriotic and war propaganda films, like The Yellow Dog. An advertisement said, “If in our great American army of millions you know just one brave lad in khaki, it is your patriotic duty and your great privilege to see this wonderful photoplay.” The ad called the film “A dramatic broadside aimed at Poodle Patriots, Back-Biters, Pessimist Pups” and promised to help stamp out “Whining Whelps, Cowardly Curs and War Liars.”

The tradition of remodeling the former Astor Market building continued in 1931 when architect Raymond Irrera transformed the dance hall space into another motion picture theater, the Thalia.

In the meantime, the Sunken Galleries had prospered. A 1920 advertisement called it “The brightest spot of Upper Broadway, catering to an exclusive clientele, who finds it so alluring, with its delightful atmosphere and spaciousness, that present-day conditions have not affected its popularity.” But it would be one of the last advertisements for the space.

Prohibition went into effect on January 17, 1920. It caused the collapse of restaurants and hotels nationwide. Thomas Healy closed his restaurants and went into the real estate business. In 1922 the building underwent another renovation. There was now a dance hall and stores where the Sunken Galleries had been, and stores along the sidewalk level.

The tradition of remodeling the former Astor Market building continued in 1931 when architect Raymond Irrera transformed the dance hall space into another motion picture theater, the Thalia. Architect William I. Hohaus put his stamp on the structure four years later, by altering part of the second floor into offices. There would be two more renovations, one in 1947 and another in 1954. The latter provided space for a bakery on the second floor.

The advent of television meant that families did not have to leave home at night to be entertained. The Thalia first changed from a cinema to a repertory theater following World War II. In 1971, according to McCandlish Philips of The New York Times, first-run motion picture theaters were having “a bad time.” On the other hand, he said repertory theaters were flourishing. Among the eleven repertory theaters in Manhattan, five were on the Upper West Side. Two of them were the Symphony and the Thalia.

But, sadly, both theaters suffered before long. In 1978 actor and playwright Isaiah Sheffer and orchestral director Allen Miller discovered the Symphony Theater, closed for years, and reopened it with “Wall-to-Wall Bach, a 12-hour music marathon. The project grew to become Symphony Space, which utilized both theaters.

In 2000 the Astor Market building was demolished for a 22-story apartment building. Symphony Space negotiated to have the theaters saved and the new structure erected around it. Why that was necessary, rather than simply building a new performance venue is puzzling, since in 1999, Isaiah Sheffer had gutted the Art Deco interiors, deeming them “unsalvageable.”

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 2527-2537 Broadway:

Meet Jennifer Brennan!