The Admaston

by Tom Miller

Dr. Thomas W. Evans was an enterprising man. A dentist, he had amassed a fortune while practicing in Paris, his most distinguished patient being Napoleon III. Three years after the emperor’s death in 1870, Evans was back in New York City, and the potential of the Upper West Side caught his attention. In 1873 he purchased the block of land from Broadway to West End Avenue, and from 89th to 90th Streets, anticipating a huge return on investment as the district developed.

When he died in 1897, the land was still vacant, and it was not until 1909 that his heirs considered selling. By then the block was surrounded by apartment houses and private homes. In November that year Robert E. Dowling purchased the Evans Block, as it was called. The Real Estate Record & Guide said it “has been regarded as the most valuable unimproved parcel held in single ownership anywhere on the west side.” Six months later Dowling sold the northwest corner of Broadway and 89th Street, and the southeast corner of West End Avenue and 90th Street to George F. Johnson, Jr. and Leopold Kahn. The men immediately laid plans for two modern apartment houses on the diagonally opposing corners of the block.

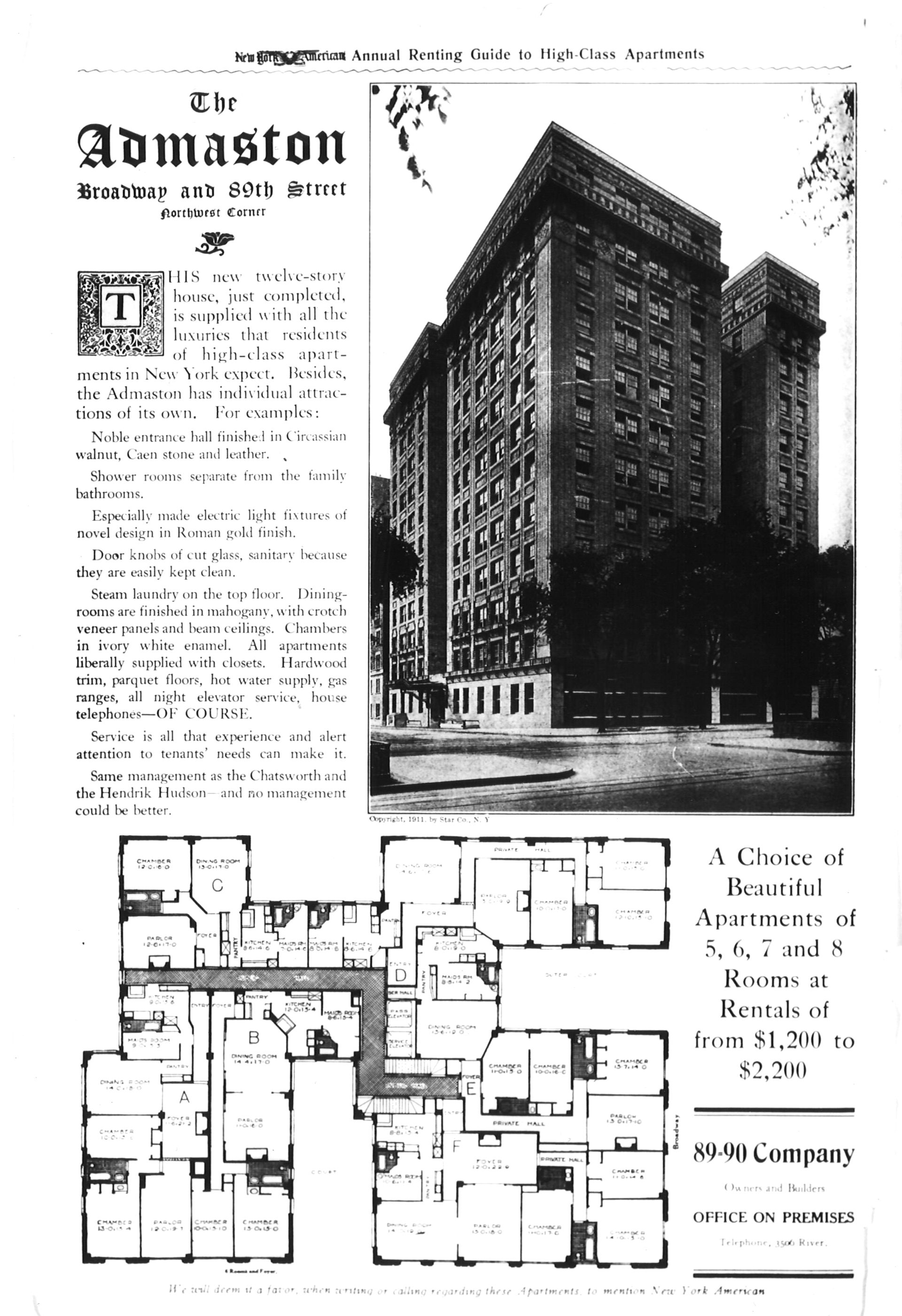

Johnson & Kahn commissioned architects George & Edward Blum to design the buildings. The Admaston, on the Broadway corner, would rise 12 stories and cost an estimated $1 million to construct—more than 28 times that much today. The Record & Guide commented on February 4, 1911, “It will have suites for sixty families and have large inner and outer courts.” Completed later that year, the apartments had five to eight rooms with rents ranging from $1,000 to $2,200, or about $5,000 per month for the most expensive in today’s dollars.

The New York and American Annual Renting Guide to High-Class Apartments said the Admaston “is supplied with all the luxuries that residents of high-class apartments in New York expect.” Among those it listed, “shower rooms separate from the family bathrooms, especially made electric light fixtures of novel design in Roman gold finish,” and “door knobs of cut glass, sanitary because they are easily kept clean.”

Residents of the Admaston had at least one servant. On September 11, 1912, 17-year-old Sophie Beckendorf answered an advertisement for a maid placed by Mrs. Solomon H. Ganz. Two days after Mrs. Ganz hired her, Sophie disappeared. Simultaneously, said The Evening Telegram, so did “a bar-pin, set with fifty-two diamonds, a coral necklace and two gold watches.” Mrs. Ganz valued them at the equivalent of $20,600 today.

The Sun reported, “This girl, who has been in the country two years, managed in that time to get the reputation of being one of the sharpest crooks in the country at the dishonest servant girl game.”

On November 4 Sophie was found and arrested. The Evening Telegram reported, “In the police station, when confronted by Mrs. Gans [sic], by whom she was identified, the girl emphatically denied having seen the complainant before.” And yet, when arrested Sophie had a porcelain box that had been stolen from the Ganz apartment. And this was not Sophie’s first such crime. The Sun reported, “This girl, who has been in the country two years, managed in that time to get the reputation of being one of the sharpest crooks in the country at the dishonest servant girl game.”

Actress Bertha Kalich, who fascinated audiences by performing in seven different languages, was a victim of the “dishonest servant girl game” the following year. Her maid, Helen Mullaney, had come with sterling letters of recommendation from millionaire socialites like the wife of Standard Oil mogul Henry H. Rogers and Alva Vanderbilt Belmont. But when Bertha discovered that several small pieces of jewelry were missing, she fired Helen. The News York Times reported on December 23, 1913, “After the maid had gone Mme. Kalich discovered that many valuable pieces of jewelry also were missing.” Unlike Sophie Beckendorf, immediately upon her arrest Helen Mullaney confessed to the thefts.

Another well-known actress living in the Admaston at the time was Roziska “Rose” Dolly, one of the famous Dolly Sisters. She married songwriter Jean Schwartz in 1913, the same year the sisters left the Ziegfeld Follies to pursue their separate careers. She explained to a reporter from The New York Press in February 1914 how she managed to simultaneously work and keep house:

I never get up before 10 o’clock in the morning when I am working. After breakfast is over the cook comes to me for orders for the day, and I tell her what we are going to have for luncheon and dinner. After that I go over the house with the maid to see what hangings need cleaning and what else should be done. Both the cook and the maid write down the orders I give, and I feel perfectly sure that everything will be carried out as I wish.

She said that a dancer could be a good housekeeper, adding “It seldom takes me more than an hour to arrange all of the details of the day so far as the housekeeping is concerned.”

In 1913 tenor Rudolph Berger married operatic soprano Marie Rappold and the couple moved into the Admaston. The following year, on February 5, he made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera House as Siegmund in Die Walküre. The New York Times reported, “aside from any question of his singing, he attracted considerable attention by wearing a wig with what may be described as a ‘Psyche knot.’” In the controversy that followed, Berger defended himself saying that the old Teutonic warriors wore their hair that way.

After the matinee performance of Gotterdammerung on February 18, 1915, Berger complained of internal pains and was unable to return to the stage. His doctor diagnosed muscular rheumatism. It was, instead, heart disease. On February 26 Berger telephoned the Metropolitan Opera to say he felt “almost recovered” and that he would return soon. Only minutes after hanging up the telephone, he suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 40.

Among the original tenants of the Admaston was the De Cordova family. Arthur De Cordova was a member of the brokerage firm of Cyril De Cordova & Brother. He and his wife, Florence Mercedes, had a son and a daughter. The family was the center of a murder mystery in 1920. On July 1 Florence and the children—Eustace was 20 years old, and Gladys was 17–went to Stonington, Connecticut for the summer, driven by the family chauffeur, Bernard B. Geissler. As was the case with many businessmen, Arthur remained in New York during the week and traveled to Stonington on the weekends.

It appears that in sending his wife to Connecticut with Geissler, Arthur De Cordova was entrusting the fox with the henhouse. Earlier, Geissler’s wife, Anita, had found a snippet of blonde hair in his pocket, and in October 1919 she found two photographs of Florence De Cordova. When she confronted her husband, he refused to discuss the matter. And so, Anita telephoned Florence De Cordova and asked her to distance herself romantically from Bernard.

Her entreaty apparently had no effect. On July 12, 1920, a Connecticut farmer, James Main, saw Florence and Bernard in a three-seated sports car outside of Stonington. He told authorities that “they appeared to be having what might be termed a hilarious time.” The good time was about to end.

Half an hour later James F. Brown drove upon a horrifying scene. Florence De Cordova’s body was sprawled in the middle of the dirt road, shot twice. The Evening World said, “Across the barbed wire fence was the chauffeur, still breathing, but evidently fatally wounded. Between the two was an army pistol.” Police noted that in the automobile were found a bottle of Scotch, partly consumed, and “many cigarette stubs.”

Florence’s body was examined by Dr. Florizel De L. Meyers of the Post-Graduate Hospital and by the Medical Examiner. (Myers was, coincidentally, her brother-in-law). They independently determined that there were no signs of an attack nor a struggle. It seemed to be a clear matter of murder-suicide.

That should have been the end of it, but two days later another physician, Frank Paine, was asked to re-examine the body. His findings were starkly different. “He said there were finger marks on Mrs. De Cordova’s throat and other evidences of a violent struggle,” said The Evening World. Both Meyer and the Medical Examiner refuted his assertions. But Paine’s findings deflected the taint of scandal from the De Cordova family. Now, according to the prosecutor, it appeared that Geissler was infatuated with Florence and “inflamed by the whiskey” he murdered her when she turned down his advances. Florence Mercedes De Cordova’s funeral was held in the Admaston apartment on July 15, 1920. Her death notice said simply that she died “suddenly.”

Florence De Cordova’s body was sprawled in the middle of the dirt road, shot twice. The Evening World said, “Across the barbed wire fence was the chauffeur, still breathing, but evidently fatally wounded. Between the two was an army pistol.” Police noted that in the automobile were found a bottle of Scotch, partly consumed, and “many cigarette stubs.”

Society appears to have accepted the story of the chauffeur’s unrequited love for Florence. On October 1, 1922, Arthur announced Gladys’s engagement to Harrison B. Moore III who came from a socially visible family. The wedding took place in All Angels’ Church on West End Avenue on February 8, 1923.

Another Metropolitan Opera tenor, Bulgarian-born Armand Tokatyan, and his wife, the former Marie Antoinette Abbey, lived in the Admaston in 1926. Just before the curtain rose for a performance of Falstaff that year, he received word that Abbey had given birth to a son. Two years later, on March 19, 1928, it happened again.

The Brooklyn Standard Union reported that just before he appeared on stage in Puniccini’s Le Rondine, he was “called to the telephone and informed of the new arrival, his second child.” The newspaper said he “not only received the plaudits of the large audience but after the opera received many personal congratulations backstage when it became known that Mrs. Takatyan had presented to the singer a baby daughter.”

Teen-aged Harold Norman Joseph lived with his family in the Admaston in 1941, as war raged in Europe. He was an avid short-wave radio operator as well as a member of the War Relief Association of American Youth. The two seemingly dissimilar interests came together that year. On February 16, ten months before the attack on Pearl Harbor which would pull the United States into the conflict, The New York Times reported, “An invitation extended by an official German short-wave radio station to American listeners to cable, collect, their choice of future propaganda talks brought at least one rebuff yesterday. Harold Joseph told the newspaper that he had send “at German Government expense” the message:

Americans would appreciate broadcast of Hitler funeral and word that the oppressed are free.

In 1960 the Admaston was converted to condominiums. In 1970 the terrazzo flooring of the spacious lobby was modernized with marble tiles and a canvas canopy was installed over the entrance; but otherwise the vintage structure remains little changed.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 251 West 89th Street:

Meet Delfina Moody and Ingrid Patricia Chez!

Meet Liz Lowy!

Meet Bridget Russo!

Meet Ira Goller!