The Narragansett Hotel

by Tom Miller

The West Side Construction Company had been in business only three years in 1905, but it had already erected several upscale apartment buildings on the Upper West Side. That year it completed another, the Narragansett Hotel, on the east side of Broadway between 93rd and 94th Streets.

The 12-story structure was designed in the Beaux-Arts style. Its tripartite design included a two-story, limestone-clad base with two stores. Beefy paired brackets upheld a full-width balcony at the third floor. The seven-story mid-section, faced in red brick and trimmed in limestone, rose to a prominent intermediate cornice supported by stone brackets identical to those at the second floor. The top two stories were clad in rusticated limestone, terminating with an understated stone parapet.

In naming the apartment hotel the Narragansett, the developers hoped, no doubt, to suggest the luxurious accommodations at Narragansett Pier, one of the 19th century’s “fashionable watering holes,” as places like Bar Harbor and Tuxedo Park were called by society writers. Apartment hotels offered the convenience of hotel living without the bother of maintaining a large domestic staff.

Typical of the first residents was Mark Shaw, described by the New-York Tribune as “one of New York’s oldest businessmen,” who was “known all over the world, as he did an extensive business.” Now widowed, Shaw was in the shipping business until his retirement in 1906. He retained his positions as vice-president of the Canadian Club and a member of the Consolidated Stock Exchange and the Produce Exchange.

On August 26, 1907, the 72-year-old was sitting alone in the lobby of the Narragansett Hotel when he complained of feeling ill. Dr. Wyle, who lived next door at 2506 Broadway, was called, but it was too late. The following day the New-York Tribune ran the headline, “Mark Shaw Drops Dead” and reported that he had suffered a fatal heart attack before the physician could arrive.

As part of their employment, the staff lived in small apartments on the upper floors of the hotel. Among them was Elizabeth Chalmers, a young chambermaid hired in the summer of 1908. In September, a resident, Mrs. Edward Gurshee discovered she was missing $200 worth of jewels. The Evening World reported, “She worried about it a good deal and she spoke to Elizabeth, who ‘did’ her room, about it. Elizabeth’s great hazel eyes opened wide when she heard of Mrs. Gurshee’s loss.” At the thought of being suspected of stealing, Elizabeth began crying. Mrs. Gurshee calmed her and apologized for her “fleeting moment” of suspicion. The theft was reported to the Narragansett’s management.

“the young woman’s slender figure was draped in what the fashion writers call an exquisite creation of blue something or other.”

Then, shortly afterward, Elizabeth “blossomed out…in a rose colored Directoire gown, gray suede shoes and silk stockings, and a hat with what looked like the year’s product of an ostrich farm, blooming and waving on it, not to speak of jewelry with which she glistened like an election parade,” said The Evening World. Her expensive wardrobe drew the attention of the management and a hotel detective began following her. She was seen in the company of a young gentleman nightly, attending the theater and spending lavishly at restaurants. Elizabeth always paid. An investigator from the police department’s Detective Bureau was notified.

While Elizabeth was at the theater on October 1, Detective-Lieutenant Conroy searched her room and broke open her trunk. “What he found there would have stocked a small jewelry store and had the makings of a pretentious lace and filmy undergarment shop,” said The Evening World. “All the stuff in the humble working girl’s trunk was worth $10,000, and much of it was recognized as having been missing from the rooms of the Narragansett’s guests.”

The newspaper said, “When Elizabeth entered her room after midnight with a swish of her silken skirts, her tall, hipless-corseted form swayed as she saw the detective and the open trunk. Then she broke down and told it all.” A call to the Imperial Hotel, where she had previously worked, revealed that a rash of burglaries had occurred there during her employment. Her plundering, at least, made her especially presentable at her hearing. “In the West Side Court to-day,” said The Evening World on October 2, “the young woman’s slender figure was draped in what the fashion writers call an exquisite creation of blue something or other.”

Living here in 1917 was Mrs. Jean Paul Kursteiner, an accomplished composer, author, pianist, and operatic soprano. Her apartment doubled as her studio where she taught female students piano, composition, musical history and theory.

On the morning of February 14, 1921, theater ticket agent William Everin was not feeling well and slept in. At 10:00 the telephone rang, and his wife, assuming it was his office calling, said he was ill, but would be into work around noon. The young man who called then hung up.

Then, at around 11:15 there was a knock on the Everin’s second-floor apartment door. Mrs. Everin opened it to find a young man who said he needed to fix the leaking radiator. Once inside he drew a revolver and threatened to kill her if she made any noise. William Erevin was still in bed, and when his wife indicated he was in the apartment, the thug forced her against the wall and wrested two diamond rings from her fingers and a gold watch from her wrist. The brazen thief then forced her at gunpoint to bring him her husband’s jewelry and $200 which was in his coat pocket. Before fleeing, he pulled the telephone cord from the wall.

“By the time of the daring burglary, tastes in apartment living were changing, and Victorian residence hotels were being supplanted by modern Art Deco apartment buildings. In response, a renovation to the Narragansett, completed in 1926, resulted in 2-, 3-, and 4-room furnished apartments.

The deteriorating conditions of the once refined Narragansett Hotel were hinted at in March 1947 when the 63 permanent residents were given 30-day eviction notices. The management cited 15 violations handed down by various city departments, saying “it would cost $30,000 to $40,000 to make necessary repairs.” On March 31 the Daily News wrote, “The tenants contend the management is seeking to get them out in order to convert to a more lucrative type of apartment dwelling.” Either way, the Narragansett did not become a luxury apartment house.

The Narragansett Hotel’s brush with celebrity occurred in the summer of 1991. On August 1, The New York Times described it as “a modest and informal 12-floor residential hotel” that “has become an unlikely Mecca.” The article said, “Cheikh Mourtada Mbacke, an aging, contemplative scion of Senegal’s venerated Muslim leader and anti-colonialist, Ahmadou Bamba, has arrived on Broadway. And his people have followed.” It continued, “The choice of the Narragansett Hotel, a home to many college students during the school year, was not the Cheikh’s; his followers in New York picked it for him.”

The location of the hotel was “near the community,” according to Mouhamadou Lamime Diagne, who explained “most Senegalese in New York live in Harlem.” The Cheikh’s arrival in New York caused a sensation. When he visited the Malcolm Shabbazz Mosque on 116th Street and Lenox Avenue on July 26 he was treated like a visiting dignitary. The New York Times said, “police barricades were set up, and worshipers craned their necks to see him, some rushing forward, trying to touch him.” Meanwhile, “At the Narragansett, the stream of visitors never lets up. ‘Eighth floor,’ Mr. Toon often answers before he is even asked at the reception booth. “No celebrities have stayed here before,’ he said. ‘They once filmed a Kojak episode here, though.’”

The Cheikh’s visit was a brief glimmer of positive press. Three years later the building had become a single-room occupancy hotel, frequented by alcoholics and drug users. On September 2, 1994, Joseph B. Treaster reported on a string of heroin-related deaths in Manhattan the previous week. “One of the men, who was 47 years old and had been living in a single room occupancy hotel at 2508 Broadway, had needle tracks on his body, Dr. [Charles S.] Hirsch said. The man went into convulsions, which often happens in drug overdose cases.”

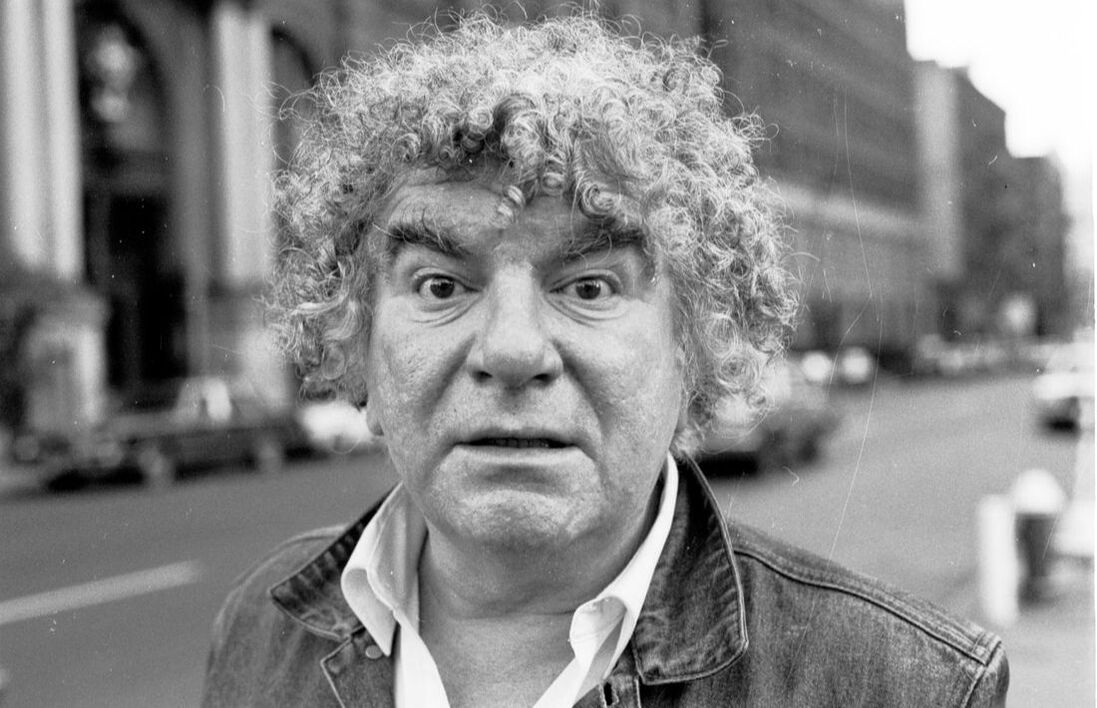

A tragic resident of the Narragansett Hotel was Leonard Melfi. He had had a long career as a playwright, both on and off-Broadway. The New York Times said, “in his early years as a playwright [he] was often mentioned with Sam Shepard and Lanford Wilson as among Off Broadway’s most promising writers.” During the 1960’s and ‘70’s, many of Melfi’s plays were staged at La Mama. He was one of the screenwriters for the 1972 Sophia Loren movie Lady Liberty, and his short play Jack and Jill was incorporated into the musical Oh, Calcutta! His play Birdbath was performed around the world.

“The tragicomic elements of his own demise would have appealed to Leonard Melfi’s artistic sense. Alcoholic playwright, once a name in theatrical circles, living alone in a single-room-occupancy hotel. He drinks, he writes, he is rushed to the hospital, he dies.”

But Melfi suffered from a severe addiction to alcohol. His good friend, playwright, and screenwriter, Joane Tedesco, had found him a ninth-floor room in the Narragansett after he could no longer afford his apartment on the Upper East Side. “There,” said The New York Times, “he continued to write and to drink, moving from bourbon to vodka. He had no telephone, so family members kept in touch by leaving messages at the front desk.”

On October 27, 2001, Melfi’s daughter, Dawn, attempted to see him. Through the door, he said, “I’m fine. Don’t worry about me.” The next day paramedics took him to Mount Sinai Hospital. He died there, alone. Unaware of who he was, and unable to contact family members, the city buried Melfi in a pauper’s grave, just before Christmas. His family would not find out about his death until April 2002. The New York Times wrote, “The tragicomic elements of his own demise would have appealed to Leonard Melfi’s artistic sense. Alcoholic playwright, once a name in theatrical circles, living alone in a single-room-occupancy hotel. He drinks, he writes, he is rushed to the hospital, he dies.” His friend, author Elain Dunay, said, “It is the best play that Len didn’t write. It has all his twists in it.”

On April 24, 2002, an 80-year-old woman, Delores Drumgold, was found dead in her room, strangled to death. She was well-known to local police. One said, “This old lady was known, God bless her, for having people over and having beer parties.” He said she treated him like a son, but sometimes “she would slap him when she was angry with him.” A month later another Narragansett resident, 39-year-old Michael Fellows, who lived on the floor above Delores, was charged in her murder.

The Narragansett Hotel, once touted as “especially suited for ladies traveling alone,” had deteriorated to what a deputy mayor under Rudolph W. Giuliani called “a scourge on the neighborhood by anyone’s reckoning.” Another renovation, completed in 2012, resulted in from eight to ten “residential hotel rooms” and one common kitchen per floor. The New York Times noted in August that year, “All are protected by a hotel worker who sits inside the front door and asks visitors, stone-faced, to show ID and sign in.”

The ground floor of the Narragansett Hotel has been modernized, but the upper floors, except for the missing cornice above the tenth floor, the Beaux Arts confection is essentially unchanged since 1905.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2508-2510 Broadway: