The Versailles

by Tom Miller

Builders and real estate developers William Gunn and Andrew Grant, partners in Gunn & Grant, were erecting apartment buildings on the Upper West Side at a blinding rate in the 1890’s. On September 24, 1897, the Real Estate Record & Guide reported they had purchased the blockfront on the west side of the Boulevard (later renamed Broadway), from 90th to 91st Street) and “will improve the same by the erection of apartment houses.” The article noted, “their architect in previous operations has been Henry Anderson.”

For the northern half of the parcel, Anderson produced a six-story apartment building faced in beige Roman brick above a rusticated limestone base. Completed in 1898, it contained two storefronts that faced the avenue. The residential doorway was placed within an ornate Renaissance-inspired entrance. In the arched transom above the double doors, the building’s name, Versailles, was announced in reverse-painted gold script. The upper floors were decorated with splayed terra cotta lintels, Renaissance-style balconies, and exuberant terra cotta floral panels. There were two apartments per floor, each with nine rooms and a bath.

An apartment in the basement was reserved for the superintendent. In 1904 J. C. Blore and his wife lived there, and it seems Blore’s assistant, Robert Harris, occupied an unused room. They all received a shocking awakening just past midnight on February 19, 1904. The following day The New York Times ran the headline, “Nearly Drowned In A Broadway Deluge / Midnight Torrent Sweeps in on Janitors’ Apartments / Thrilling Tales of Escape.” The article explained that the 36-inch diameter water main at the corner of 91st Street and Broadway had burst. Among the several janitors’ families in the neighborhood who found themselves suddenly in chest-deep water, of course, was the Blores. The article said they waded to safety and “all had to be clothed by tenants.” The three-foot-deep inundation of the basement did more than temporarily evict the Blores. The water poured into the furnace, dousing the fire, and causing the tenants to endure the February cold for hours, as well as a lack of running water.

The southern shop on Broadway was home to Irving S. Rahn’s menswear store by 1907, and the Tschappe & Reich drug store occupied 2459 Broadway at least by 1913. The pharmacy would be a neighborhood fixture for decades.

The three-foot-deep inundation of the basement did more than temporarily evict the Blores. The water poured into the furnace, dousing the fire, and causing the tenants to endure the February cold for hours, as well as a lack of running water.

Rent for a 9-room apartment in 1909 was $1,900—around $4,650 per month today. Among the affluent tenants were John W. Bird, who maintained two private yachts, the Adeltha and the Dervish; and attorney Charles Edgar Littlefield and his wife, whose summer home was in Rockland, Maine.

Littlefield had been a United States Congressman until his retirement from politics in March 1908. The New-York Tribune said that “through his own efforts [he] rose from a carpenter’s job to be a powerful figure in Congress.” He was now a partner in the law firm of Littlefield & Littlefield with his son, Charles W. Littlefield.

In the summer of 1913, the elder Littlefield was accused of graft by the colorful showman Colonel Zack Mulhall. According to The Sun, Mulhall said he had accepted gifts of money “from the manufacturers’ lobby and of permitting the manufacturers to pay his hotel and traveling expenses.” Littlefield was not around to answer the charges, having sailed for Europe a month earlier. His family did not seem over-eager to give out details. “At the home of his son, Charles W. Littlefield, it was said last night that his mail is forwarded to an address in Paris, but that the family is not certain of his whereabouts at the present time.” The brush with scandal went nowhere.

On June 13, 1915, Littlefield underwent an operation at the Post-Graduate Hospital. Everything seemed to have gone well and he was soon released. But ten days later a blot clot formed, which resulted in an embolism. In minutes the 64-year-old was dead. Mulhall’s accusations had been long forgotten and newspaper accounts of the former Congressman’s death were filled with his many accomplishments.

Residents of the Versailles got a Christmas Eve scare in 1915 after a fire broke out in the basement of the Tschappe & Reich drug store. The N.A.R.D. Journal reported, “the crowd of Christmas merrymakers were gathered to witness it necessitated the calling out of the reserves of the West One Hundredth street police station.” Happily, the fire was quickly extinguished, and the damages were small.

A resident who appeared in newspapers for somewhat embarrassing reasons was Mrs. Hester A. Booth. On December 27, 1916, The New York Times reported that Stella Anna Pringle had filed to overturn the will of her husband, Alexander Young Pringle. She said that she suspected it was a forgery, or “if he did make the will, it was not his unrestrained act, but was obtained through the undue influence” of several women, including Hester Booth. Pringle had left his wife $50,000 and more than $500,000 to “women friends.” The Pringles’ housekeeper, Ethel Crane, received their country place at Eatontown, New Jersey, and $50,000; Hester’s sister, Belle K. Shute, received $25,000; and Hester’s “residuary bequest” was “more than $400,000,” according to the article. Stelle Pringle had every reason to be upset. That amount would translate to more than $12 million today.

If Hester were concerned about the taint of scandal, the New York Times diplomatically noted that the Pringles “had not lived together in the last years of Mr. Pringle’s life,” and added, “Mrs. Booth and her sister, Mrs. Shute, were old friends of the Pringle family, and were on close terms with the decedent’s father and mother, from whom he inherited his property.”

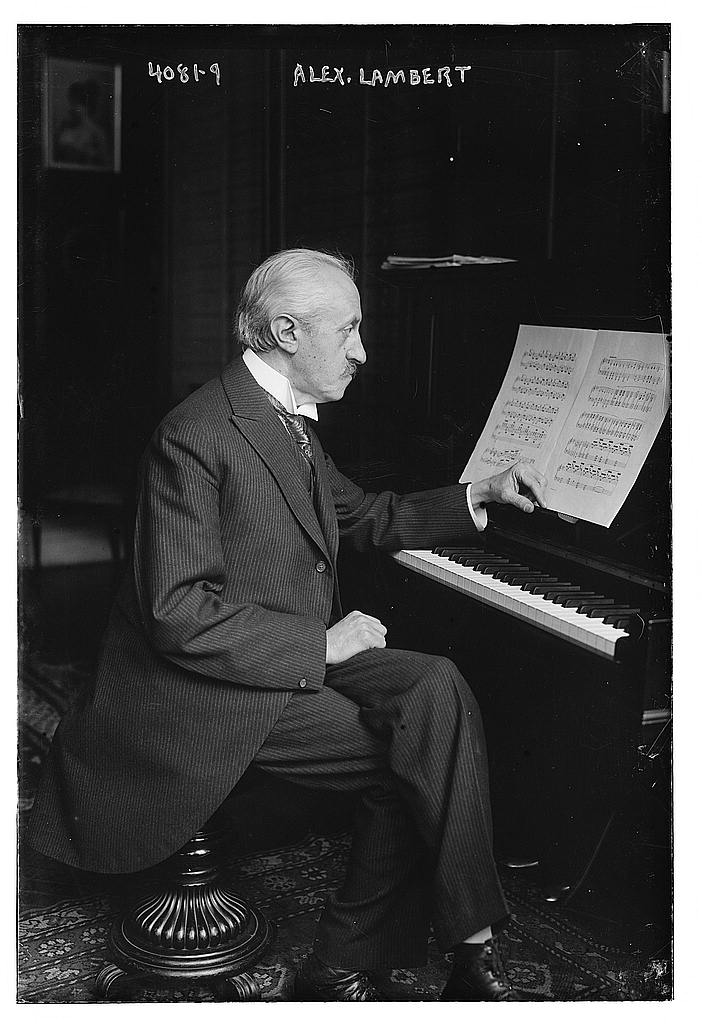

Following the summer season of 1918, pianist and instructor Alexander Lambert moved into the Versailles. Renowned instructors could afford to lead comfortable lives, and on August 19, 1918, the Musical Courier reported, “Alexander Lambert, the pianist, and pedagogue, is at Lake Placid, N.Y., whither he has gone to escape his threatened annual attack of hay fever. The earlier part of the summer was spent by Mr. Lambert at Avon, N.J. (where he did some teaching), and at Highmount, N.Y. After a short September visit to the White Mountains, Mr. Lambert will return to New York and settle in his new apartment studio at 250 West Ninety-first street.”

Living in the Versailles at the time were Mr. and Mrs. Tenbrook B. Morse, whose apartment was on the sixth floor. Mrs. Morse’s valuable collection of jewelry was in part due to her husband’s position with Tiffany & Co. On November 17, 1918, a new elevator operator was hired. That night he took the Tenbrooks, dressed for an evening out, to the lobby. They returned at about 1 a.m. and, according to the New-York Tribune, “found the elevator stalled between floors, its bell plugged with paper and the cable twisted on the drum.” The Tenbrooks walked up to their apartment where everything initially looked normal. “There was no disorder in their apartment or evidence of violence in gaining entrance to it,” said the article. Nevertheless, not only had the new elevator operator disappeared but so had one of Mrs. Tenbrook’s jewelry cases, containing items valued at $86,000 in today’s money.

Throughout the years, Alexander Lambert’s name appeared in print repeatedly. On May 5, 1922, he hosted a dinner party in the apartment in honor of S. L. Rothafel, director of presentations at the Capitol Theater. Lambert was recognizing Rothafel’s “work in developing the music for the exhibition of motion pictures,” explained the New York Herald. Among the well-known figures of the musical community at the dinner were violinists Leopold Auer and Jascha Heifetz; piano maker Frederick Theodore Steinway; and Dutch-born conductor Willem Mengelberg.

The newspaper noted that the groom “is thirty years the senior of his wife.”

Among the accomplished students of Lambert was Polish-American pianist Josef Hofmann. He had already achieved relative fame when he returned to visit Lambert, who was giving a lesson to young Betty Short. On April 2, 1928, The New York Sun reported, “New York friends of Josef Hoffmann, the pianist, confirmed today reports of the marriage of Mr. Hoffmann to Miss Betty Short, 21 years old, a student whom he met at the studio of Alexander Lambert.” The newspaper noted that the groom “is thirty years the senior of his wife.”

Another musical celebrity of a sort, Madame La Puma, arrived at the Versailles not long afterward. Born Giuseppina La Puma, she had married opera singer Ottavio Masiello. In 1933 she brought her daughter, mezzo-soprano Alberta Masiello to New York. Giuseppina became an impresario and changed her name to Josephine La Puma, or Madame La Puma. She established The Mascagni Opera Guild, an alternative to the mainstream opera companies, which provided young singers, including her daughter, with professional opportunities. Unfortunately, rising auditorium rents and other issues threatened her company.

In his 2010 book Fortissimo, Backstage at the Opera with Sacred Monsters and Young Singers, William Murray writes, “To free herself from harassment by craft unions and tone-deaf bureaucrats, she dissolved the Guild and reorganized it as the Opera Workshop, incorporating it as a nonprofit educational institution.” Another money-saving idea was to move the Workshop into her second-floor apartment. One does wonder what the other occupants of the Versailles felt about grand opera resounding the halls. On June 23, 1954, for example, on the list of “Events Tonight” in The New York Times, was “’La Boheme,’ La Puma Opera Workshop, 250 West Ninety-first Street, 7:45.”

By 1965 the southern store was home to Harold’s Fish Market, and in 1997 it became Barzini’s “mini-mega store,” which remains. A renovation of the building in 2010 increased the number of apartments on the second and third floors to four. Overall, the Versailles retains its patrician appearance of 1898.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 250 West 91st Street: