Astor Court

by Tom Miller

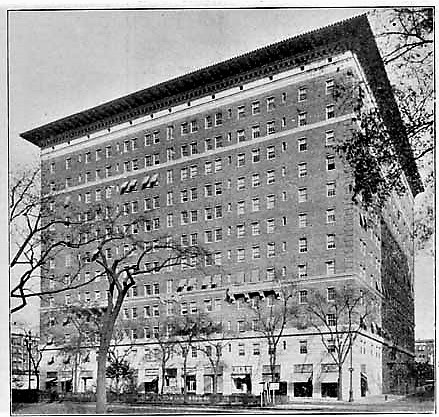

On June 20, 1914 the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide reported that architect Charles A. Platt had filed plans for a 12-story “store and apartments” building to fill the eastern blockfront between 89th and 90th Streets. The million-dollar structure, more than 25 times that amount in today’s money, would be the first large-scale project for the 23-year old multimillionaire, Vincent Astor.

Completed two years later, Platt’s sedate brick neo-Renaissance structure sat on a two-story rusticated limestone base. The understated facade could boast little ornamentation. Ambitious stone balconies surmounted the entrances on 89th and 90th Streets, and two others clung to the fifth floor cornice on the Broadway elevation. The crowning copper cornice made a statement. Projecting fully eight feet from the facade, it was brilliantly painted in gold and red.

Most innovative was Platt’s treatment of the courtyard within the U-shaped structure. Rather than using it as a turn-around for automobiles picking up and dropping off residents, he created a restful refuge. The New York Times noted it “is adorned with a fountain in the centre of a formal garden.”

Despite the presence of the well-known Astor Court Building on West 34th Street, or perhaps because of it, Astor named the new structure the Astor Court. Residents entered through two entrances, under glass marquees, at No. 205 West 89th Street and 210 West 90th. Stores installed in the Broadway ground floor provided additional income.

On October 31, 1916 The American Architect complained of overall disappointing apartment design. “So much speculative building and attendant poor architecture have characterized this type of building in New York.” But it pointed to the Astor Court as an example “of what can be accomplished,” adding “The features of domesticity, privacy and refinement are everywhere apparent in the Astor Court Apartments.”

The New York Times, on April 23, had called the building “noteworthy” and “decidedly the superior of many of the Park Avenue houses” in “genuine architectural dignity.”

Astor’s marketing included opening a model apartment in the newly-finished building. An advertisement in the New-York Tribune on June 18, 1916 announced that it was “open for inspection.”

A Model Apartment completely furnished by the Interior Decoration Division of Gimbel Brothers, as a suggestion to lovers of fine apartments everywhere. Furniture, Hangings and Floor Coverings. You are cordially invited to enjoy this exhibit.

There were eight apartments per floor, ranging from seven to nine rooms. It would quickly become home to well-to-do residents–some them both celebrated and colorful.

On May 11, 1916, as the Astor Court was nearing completion, a cable from London reached The New York Times that announced the marriage of Winfield R. Sheehan and Kay Laurell. Both were well-known in the entertainment field.

Sheehan, who had started out as a reporter for The Evening World and then as secretary to former Police Commissioner Rhinelander Waldo, was now a vice-president of Fox Film Corporation and one of its major stockholders. Kay Laurell was a Broadway actress whom The New York Times pointed out “was considered one of the handsomest girls in Mr. Ziegfeld’s last year’s ‘Follies,’ when the revue was presented at the New Amsterdam.” Along with the news of the marriage, the article managed to remind readers that Kay had appeared on stage in an “exotic scene…wrapped in gauze and stage sunlight” and “at the end of one of the acts strapped to the muzzle of a cannon.”

In fact, Kay Laurell, who started out as an artists’ model as a teenager, had been discovered by Florenz Ziegfeld and became famous for her striking beauty and her willingness to disrobe.

Two months earlier, opera star Geraldine Farrar was married to Lou Tellegen, considered one of the handsomest actors on screen or stage. On February 6 The New York Times explained “The prima donna and the actor first met in New York last Winter, when Miss Farrar was singing at the Metropolitan and Mr. Tellegen was appearing in the principal role of ‘Taking Chances.'” By now they had appeared in three silent films for the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Film Company. She was his second wife.

Both sets of newlyweds moved into the Astor Court Apartments.

On October 31, 1916 The American Architect complained of overall disappointing apartment design. “So much speculative building and attendant poor architecture have characterized this type of building in New York.” But it pointed to the Astor Court as an example “of what can be accomplished,” adding “The features of domesticity, privacy and refinement are everywhere apparent in the Astor Court Apartments.”

Irene Taylor also lived in the Astor Court at the time. The well-to-do widow had recently moved to New York from Minneapolis. Although she was not famous, her name would soon become well-known to newspaper readers.

William Baer Ewing was president of the Ford Tractor Company, based in Minneapolis. He was obligated to come to New York after he was indicted by a Federal Grand Jury for mail fraud “in connection with the exploitation of the company’s stock,” as explained by The Evening World. Some eyebrows were raised when he chose not to check into a hotel, but moved into Irene Taylor’s apartment.

The unseemly arrangement did not escape the notice of Edward L. Kelly and Daniel Finn. On August 13, 1917 they knocked on the apartment door. When Ewing answered, they flashed a badge and identified themselves as Federal agents Hollahan and Doherty.

When Ewing asked them the purpose of the call, one replied “You know the Mann white slave law.” (The 1910 Mann Act made transporting females across state lines for the purposes of prostitution a felony.) Ewing immediately realized he was the target of extortionists.

The men suggested they all walk to Riverside Drive where they sat on a bench. Ewing later testified that, playing along, “I asked them what it was worth to hush up the matter and they told me that as I was a pretty good sort of a little fellow they would not go hard with me and $5,000 would do.”

The next morning Ewing was in office of Federal authorities, accompanied by his attorney. They provided him with marked bills to take to his appointment the following afternoon. When the payment was made, undercover detectives moved in and arrested the crooks.

Nevertheless, the embarrassing fact that Irene Taylor had a man living with her was now well publicized. The Evening World noted that at the trial Kelley was asked “how he knew that Ewing was living with a woman not his wife.”

In the meantime, things were not going well in the Sheehan apartment. On July 3, 1917 Kay went to White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. On the 16th, Billboard magazine explained she “is recovering from a nervous breakdown.” The article added “Mrs. Sheehan retired from the stage when she became the wife of Winnie Sheehan. It is said as soon as her health is restored she will return to the footlights in a musical production.”

But there was more to the story. The following day the New-York Tribune reported she had sued for separation. “The actress alleges cruelty,” said the article, adding “Shortly after the marriage, she says, Sheehan commenced a course of unkind, harsh and tyrannical conduct toward her.”

Although the couple never divorced, they never reconciled. Laurell returned to the stage and to her scandalously revealing costumes. She appeared in Zeigfeld’s patriotic pageant The Spirit of the Allies in 1918. H. L. Mencken described her as being gifted “with all the arts of the really first-rate harlot” in his 1918 In Defense of Women.

Still married to Sheehan, she died in childbirth in 1927. The father was the son of Yukon lumberjack and secret agent Klondike Joe Boyle.

Winfield Sheehan left New York when the motion picture industry moved to Hollywood. He won an Academy Award as Fox studio head for Cavalcade and was nominated three more times.

Another of the original tenants related to the theater were William Frederick Peters and his wife. The composer wrote scores for plays and then films. When silent movies were screened they were accompanied by musical scores. Among those written by Peters were scores for Way Down East, Orphans of the Storm and Little Old New York.

His wife left the theatrical side of things to him, focusing instead on entertaining. On April 26, 1918, for instance, The Sun announced “Mrs. William F. Peters of 205 West Eighty-ninth street, will entertain Saturday afternoon, May 4, in honor of Miss Priscilla Bigelow of Boston.”

Sometime before this Geraldine Farrar and Lou Tellegen moved to No. 20 East 74th Street and turned their Astor Court apartment over to Geraldine’s parents. Her father, Sidney Douglas Farrar, had been a sort of celebrity in his own right. A professional baseball infielder, he played from 1883 through 1890.

Henrietta Barnes Farrar invited a dozen men and women, four reporters and two publishers to her drawing room on May 1, 1920. The guest of honor was Mary McEvilly, who claimed to be the spiritual conduit of 15th century Hindu spirit Meslom.

According to The New York Herald, “It was the largest gathering, both Mrs. Farrar and Miss McEvilly explained, that Meslom ever had been called upon to greet at one time through her pencil point, but the medium and the hostess expressed assurance of a satisfactory sitting.”

Participation from the apprehensive participants was tepid “until a question on prohibition was injected into the ether. That broke the ice and queries flowed freely thereafter.” Meslom correctly predicted that the “‘drys’ will lose.”

Reporters would haunt the 90th Street entrance of the Astor Court the following year in August in hopes of catching Geraldine Farrar coming or going from her parents’ apartment. The diva had locked Lou Tellegen out of the 74th Street townhouse, not even allowing him to retrieve his clothing.

Tellegen had just returned to New York from a “shack” he had rented in Long Beach, California. Geraldine told her friends “he was there in order to have the quietude necessary to learn the long role in his new play.” (That play, L’Homme a la Rose, was being produced by Archibald Selwyn, who perhaps not coincidentally lived in the Astor Court.) Perhaps Geraldine discovered that her husband’s female secretary was also there.

On August 7, 1921 The New York Herald surmised “Whatever has come about to disturb the serenity of the married life of Lou Tellegen and Geraldine Farrar, it is of recent development.” The journalist suggested it could be the stark differences in the current successes of their careers. While Geraldine Farrar continue to be in high demand on the operatic stage, she was equally popular in films. Between 1915 and 1920 she had made more than a dozen motion pictures including Cecil B. De Mille’s 1915 Carmen. Tellegen, on the other hand, had hit his professional nadir.

“It long has been the subject of comment in theatrical circles that Miss Farrar so patiently continued her interest in Tellegen’s enterprises. Not a single one of them has met with success in New York. He was last seen in a play by Augustus Thomas called ‘The Blue Devil,’ which failed so completely that it was never seen in this city.”

Attempts to find her at the Astor Court were unsuccessful. On August 7 The New York Herald reported “At 210 West Ninetieth street, the apartment house in which Miss Farrar provides a home for her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Farrar, it was [said] ‘She comes here sometimes, but not to-day.'”

In retaliation Tellegen filed for separation; but his attorneys had a challenging task in serving papers on Geraldine. Five paid witnesses loitered about the northwest corner of 74th Street and Central Park West, where they could see the Tellegen house. On the evening of August 4, after they reported that she left in a car with her parents and two other women, a lawyer set an ambush.

When the automobile returned at around 11:20 p.m., the witnesses rushed up, pretending to be fans. As Geraldine stepped out, one said “Is this Miss Farrar?” Suspecting nothing more than a request for an autograph, she answered “Yes, I am Miss Farrar,” at which point the woman said “I have a letter for you.” The attorney quickly thrust the envelope at Geraldine.

The New York Herald reported that she “did not take it, but quickly jumped out of the car and hurried into her home, calling out to the supposed admirer as she did so: ‘That was very nice of you.'” The envelope had fallen to the floorboard of the automobile. The process server picked it up and handed it to Henrietta Farrar. Since it had touched Geraldine, it was deemed served.

Tellegen’s complaint, it turned out, was that Geraldine “was unwilling to rear a family, as she deemed it incompatible with her career as an artist,” according to The New York Herald on August 9. In fact, Tellegen had carried on several affairs during the marriage.

The irate star agreed to relinquish her husband’s clothing; but she refused to allow him back into their home to retrieve them as he requested. Neither would she send them to his hotel. Instead she sent them to the Manhattan Storage Warehouse where, she said, “he is at liberty to call for them.”

Her parents continued to be in the scopes of the press. The New York Herald even tried to find her at the Farrar summer home at Chateaugay Lake in the Adirondacks.

The New York Herald reported that she “did not take it, but quickly jumped out of the car and hurried into her home, calling out to the supposed admirer as she did so: ‘That was very nice of you.'” The envelope had fallen to the floorboard of the automobile. The process server picked it up and handed it to Henrietta Farrar. Since it had touched Geraldine, it was deemed served.

Tellegen’s life (including two more marriages, to actresses Nina Romano and Eve Casanova) following his 1923 divorce from Geraldine would be tragic. His career had relied greatly on his good looks; but on Christmas Day 1929 he fell asleep while smoking. His face was seriously burned.

Following extensive reconstructive surgery in 1931, he became increasingly despondent. On October 29, 1934 while a guest in a Hollywood mansion, he locked himself in a bathroom, then committed suicide by stabbing himself seven times with a pair of scissors. Reportedly his body was surrounded by newspaper clippings of his former stellar career.

When Geraldine Farrar was notified of his death, she famously replied “Why should that interest me?”

In the meantime, Archibald Selwyn who had attempted to help Tellegen in 1921 lived on with his wife in the Astor Court. Like Winfield Sheehan, he had gotten in on the ground floor of a major film company. He and his brother Edgar, had joined Samuel Goldfish (who was later professionally known as Samuel Goldwyn) in forming Goldwyn Pictures Corporation.

Selwyn divided his time among writing screen plays, managing New York theaters and producing plays. He and Edgar, as Selwyn & Company, erected three New York theaters, the Apollo, the Selweyn and the Times Square. They produced the first Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Jesse Lynch Williams’s Why Marry? in 1917.

When his sister, actress Rae Selwyn was married to F. Maitland Goldsmith on March 28, 1922, the celebrity-filled reception was held in the Astor Court apartment.

In 1924 the Selwyn brothers parted ways and Archibald (known popularly as “Arch”) continued producing plays like Noel Coward’s 1925 Easy Virtue and his 1928 This Year of Grace.

Of course not all the residents of the Astor Court were in the theatrical field. Ernesto G. Ros was one of the owners of the Santa Fe sugar central–a massive sugar processing firm–in Santo Domingo. When his daughter Flora became engaged to William H. Davis in May 1922, the New-York Tribune described it as being “of interest” to society. The wedding was performed on October 26 in the fashionable St. Thomas’s Church on Fifth Avenue, and the reception held at Sherry’s.

Less uplifting press surrounded Clarence G. Hellman earlier that year. The 47-year old was the head of Hellman, Straus & Co., lace manufacturers and importers. But the firm was in deep financial trouble and on February 10 an application for receivership was made in the United States District Court. The papers showed liabilities amounting to $950,000–a staggering figure approaching $14 million today. The pressures were too much for Hellman.

That night as his partner, Milton Straus, prepared to go home he stopped by Hellman’s office to say good-night. He found the door locked and there were no reply from inside.

Straus and a salesman, Herman Simon, stood on chairs to look into the transom. Hellman, who was at his desk slumped forward, did not respond to their shouts. When a policeman was called and the door broken in, it was discovered that Hellman had shot himself in the head with a pistol.

The Astor Court, unlike some hulking apartment houses from the beginning of the century, did not decline. It continued to house well-heeled residents like August W. Kelley, retired vice president and trustee of the Union Trust Company. He died in his apartment on December 4, 1930. The well-known urological surgeon Dr. Emanuel Donheiserf and his wife, Sally, lived here in the 1960’s; as did actor-director Stanley Prager and his wife, television and screen actress Georgann Johnson.

Prager had been a stage and film actor before going into directing. He told an interviewer in 1969 that he played “all the parts that Phil Silvers wouldn’t play.” He said that directing television commercials gave him the financial independence to do projects he liked. Not wanting to be tied down to a single activity, he sometimes gave up directing highly successful television shows. He directed “Car 54, Where Are You” for just one season, and “The Patty Duke Show” for two.

On May 26, 1985 Michael DeCourcy Hinds, writing in The New York Times, called the Astor Court “one of the best examples of the dozens of 13-story buildings erected along Broadway” at the time of its construction. He noted “The building is now being converted into cooperatives and Stephen B. Jacobs, a Manhattan architect, has designed 10 new penthouse apartments on the roof.” The renovations were completed later that year.

Architecturally, little has outwardly changed to Vincent Astor’s and Charles A. Platt’s bold residential project. And although the protruding copper cornice no longer wears its exotic red and gold paint, it remains a showstopper.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses currently at 2420-2494 Broadway:

Meet Gregg Boisjolie!

Coming Soon!

Meet Sabine Stezenbach!