The Fife Arms

by Tom Miller

In 1900 the seven-story Fife Arms apartment building was completed at the northwest corner of Broadway and 87th Street. Designed by George F. Pelham, its Renaissance Revival design included a rounded bay at the corner. Other subtly curved bays along both facades resulted in a gentle undulation. Stores occupied the ground floor along Broadway, while the handsome porticoed residential entrance was placed around the corner 251 West 87th Street.

There were 36 apartments within the Fife Arms—ranging from five to seven rooms. They filled with financially comfortable residents, like Cleo Montague, who moved into the building following the death of her husband in 1900. Mrs. Montague entrusted her financial affairs to broker William E. Hardt, who turned out to be unscrupulous. But if Hardt believed he was dealing with a naïve female, he was mistaken. It did not take Cleo Montague long to uncover her broker’s treachery, and on November 9, 1901, The New York Times reported she had had him arrested “upon a charge of grand larceny.” She had entrusted him with a total of $7,800 in stocks and cash for investment (more than a quarter of a million in today’s dollars), which he had taken for his own use.

Another of the original residents was wealthy metal merchant Charles Wessell, who lived here with his wife and unmarried sister. The New York Times described him as “one of the best-known metallurgists in the country,” adding, “he invented what is known as the Wessel silverware.” Wessell’s old New York pedigree was reflected in his membership in the Holland Society.

Wessell was a large man, weighing about 225 pounds, according to newspaper reports. On December 30, 1902, he pushed his way through “an enormous crowd at the Rector Street station of the Ninth Avenue Elevated line,” reported The New York Times. The Evening Telegram confirmed, “The train was very much crowded.” The strain of pushing his way through the throng was too much for the 68-year-old’s heart. The Evening Telegram reported, “He was puffing with the exertion, and as the train neared the Cortlandt street station on the Ninth avenue line, the man gave a gasp and fell backward. He died instantly.”

A bizarre incident played out here in the fall of 1903. Mary Matson came to live in the Fife Arms with her aunt, a Mrs. Sorensen. The teen, who had come to America with her parents from Sweden, hoped that living in Manhattan would make it easier for her to find work. In October 1903, Mary advertised for a job as a servant. A man answered the ad, Mary proved acceptable, and he “engaged the girl to go to Providence R.I., to be employed by a woman of his acquaintance,” according to The Sun. In fact, the imposter was what police would later describe as “a procurer”—one who dealt in White Slavery, or forced prostitution.

Each time he tried to escape, she threatened to scream.

On October 16, Mary boarded a train for New Haven with him. There, he told her, he expected to hear from the Providence woman. He engaged a hotel room for the teen “on the pretext that it was too late to go to Providence.” But once he attempted to share the room with her, Mary was onto him. And the would-be abductor found the tables turned.

Mary rushed from the room, taking a chair with her. She imprisoned him inside, by wedging the chair against the door and sitting on it all night. Each time he tried to escape, she threatened to scream. The following morning, as reported by The Sun, the feisty teenager “took him by the arm, threatening all the time to shout if he tried to run away, and made him bring her back on the train to this city.” He escaped through the crowd at Grand Central Station. Mary Matson had had her fill of the big city. The article noted, “According to an acquaintance, she has now gone to her parents’ home at Sewaren, N.J.”

Living here at the time was Mary Forst Collins Walton, the widow of stockbroker James Morris Walton. Born in England in 1843, she was, like her husband, a Quaker. He had died in 1874. Both their stories were inspiring.

Born in July 1838, James Walton graduated from Haverford College in 1856. An ardent abolitionist, he joined the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1859. Despite his being a Quaker, he enlisted in the Union Army in 1863 and served as an officer in the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry, a famous Black regiment. (Black regiments were always commanded by white officers.)

Like her husband’s, Mary’s concern for the condition of Blacks was noteworthy. The New York Times recalled in 1904, “after the civil war, being then Miss Collins of Philadelphia, she went to Norfolk, Va., and was one of the first of the women of the North to teach the newly emancipated slaves.” She continued that work the following year at Lady’s Island, South Carolina. She and James were married in 1867. The couple moved to New York City, where Mary founded the Mary F. Walton Free Colored Kindergarten.

Mary died in March 1904. She had left a typewritten statement directing her family to have her body cremated “and the ashes thrown away.” She also requested that there be no funeral.

An advertisement for a vacant seven-room apartment in 1905 described the “exceptionally fine” suite as having “large, light, sunny rooms and bath.” The annual rent was $1,200, or about $3,175 per month in today’s money.

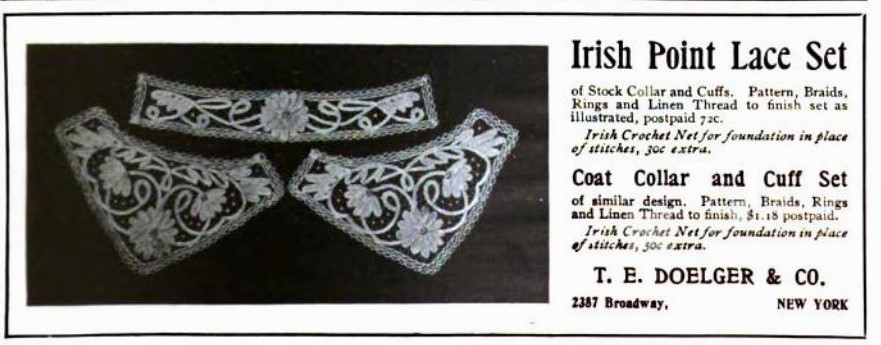

In the meantime, the Broadway commercial spaces had filled with a variety of tenants. The Clark Estate, owners of vast amounts of Upper West Side properties, operated its real estate office from 2381 Broadway through at least 1908. George Schwegler’s real estate office was next door at 2383 in 1909. And at the far end of the row, T. E. Doelger & Co.’s “art needlework” store occupied 2387 in the first years of the 20th century.

Paul Puttmann and his wife, Edith, lived in the Fife Arms by 1907. Puttmann was the senior member of the importing and exporting firm Paul Puttman & Co. The couple had married on October 3, 1896, in Canada and now had a daughter and a son. They maintained a summer home in New City, New York.

Edith was in the back of their large touring car on the evening of October 26, 1907. Her chauffeur, James Martin, crossed the streetcar tracks at 42nd Street and Madison Avenue, then paused for traffic. Unfortunately, the rear portion of the automobile had not cleared the tracks. The New-York Tribune reported that the streetcar “crashed into the rear of the machine with terrific force.” Patrolman Elmer B. Roth was standing directly next to the car when the accident occurred. The article continued, “Mrs. Putnam [sic] and the chauffeur…were thrown out.” Luckily for Edith, the policeman caught her before she hit the ground.

Both Edith and Paul Puttmann were born in Germany. Paul came to the United States around 1889, but unlike his wife, he never became a citizen. That would cause problems for Edith and the children in 1917. Edith took them to Europe that spring. Unfortunately, the United States declared war on Germany on April 4, 1917. Because Edith was a native of Germany and Paul was still a German citizen, she was refused re-entry into the United States. Although the children were permitted to sail without her, Edith Gretchen chose to stay with her mother while her brother sailed home alone. The two traveled to Switzerland, where Edith was “interned” in Lucerne, as described by The Evening Telegram.

Two years later, on July 17, 1919, The Evening Telegram reported, “Mrs. Paul Puttmann, of No. 251 West Eighty-seventh street, and her daughter, Miss Edith Gretchen Puttmann, were the happiest passengers on the Pesaro.” The article noted that “Mrs. Puttmann was interned until after the armistice was signed.”

But soon after returning to the Fife Arms, Edith realized that her husband had not been wanting for feminine companionship in her absence. On September 14, 1920, The Evening World reported that she had sued for divorce. Among the points brought up in court was that not only did Puttmann maintain the city apartment and the house in New City, but “he maintains a third establishment [i.e. apartment] in Waverly Place, the home of a protégé with a young child, at an annual cost of $10,000.”

The widowed socialite Maude Littlefield Baillard lived in the Fife Arms by 1912. On November 29 that year she “took tea” in the Plaza Hotel with friends, and as she left, she noticed a gold mesh bag on the carpet. The New York Press reported, “In the bag were several hundred dollars in bills of large denominations and a chamois-lined silk pouch containing jewelry valued at several thousand dollars.” Maude turned the bag into the hotel office and left her card.

On December 2, the bag’s owner dropped by Maude’s apartment to express her thanks. The New York Press wrote, “Both of the women recognized each other at once.” The pair had attended Mrs. Lasell’s Select School for Girls near Boston as young women. It was an unexpected and happy reunion after more than ten years.

[Jay Gormey’s] most famous song, perhaps, was the Depression era, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”

A visit to the west coast Florida town of Belleair in 1917 would change the course of Maude’s life. The Editor & Publisher reported on April 24, 1919, that she found the town to be beautiful. The article said, “It was not long before Mrs. Baillard had discovered other beautiful resort towns along the West Coast, such as Tarpon Springs, Sarasota, Bradenton, Winter Haven, Fort Myers, and St. Petersburg.” She went to the town fathers in each place, saying, “What’s the use of being beautiful if nobody knows about it? There are thousands and thousands of Northerners who would be overjoyed to come down to the West Coast instead of the East Coast if you’d only let them know how delightful it is here.”

The mayors and town councils, however, had no inkling of where to start. And so, Maude gave up “society and club life in New York City,” as worded by Editor & Publisher, to start her own promotional business for the West Florida towns. By flooding the Northeast newspapers with full-page ads, she changed the face of Western Florida within a few years.

There were several musical tenants in the Fife Arms in the early 20th century. By 1910 Florence Haubiel Pratt was a resident, her apartment doubling as her piano studio. Describing herself as a “pianiste,” she advertised, “Thorough training in touch, technique, style, repose, ensemble, harmony and analysis.”

Another musical tenant was H. R. Rumphries, “voice specialist.” He marketed himself as a “teacher of voice production and the art of singing,” saying he prepared pupils “for Church, Concert and Oratorio.”

And in 1922, composer Abraham J. Gormey and his wife, the former Edelaine Roden, moved in. The newlyweds were both graduates of Michigan State University. Born in Russia, Gormey had fled a pogrom in 1906 with his family. By the time the couple had moved into the Fife Arms, he had changed his professional name to Jay Gormey. In 1923 he was working for the theater owners, the Shubert brothers, “in association with Sigmund Romberg and Alfred Goodman,” according to The Michigan Alumnus. He was also under contract for production music with J. B. Harms, Inc., publishers.

Gormey would write the scores for several Broadway shows while living here, including Top Hole, Vogues of 1924, and Merry-Go-Round, as well as music for shows like The Ziegfeld Follies. His most famous song, perhaps, was the Depression era, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” The Gormeys left the Fife Arms in 1933 to move to Hollywood to work for Fox Studios.

A renovation completed in 1963 resulted in seven apartments per floor. In the 1970s the stores were home to 4 Brothers Restaurant at 2381 Broadway, Moniek’s grocery at 2383, and Neet Cleaners & Dyers in 2387. Later tenants included the Video Vault at 2385 Broadway, the Saigon Grill at 2381, and the Hot & Crusty Bagel Café at 2387. In 1997 the four stores were combined to form two.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2381-2387 Broadway: