Hotel Bretton Hall

by Tom Miller

In 1902 developer brothers James and David Todd commissioned the fledgling architect Harry B. Mulliken to design a minor structure–a one-story wooden tool shed on West 114th Street. It may have been a test of sorts, one which Mulliken apparently passed. The following year Mulliken and his new partner, Edgar Moeller were working on three substantial hotel commissions for the Todds, the Hotel York at Seventh Avenue and 36th Street, the Aberdeen Hotel at 17 West 32nd Street, and the Bretton Hall Hotel, which would engulf the entire eastern blockfront on Broadway from 85th to 86th Street.

The Todd brothers had purchased the undeveloped Bretton Hall site from Le Grand K. Pettit. They took out a $1.25 million building loan toward Mulliken’s total projected construction costs of $1.55 million–just below $47 million today. The architect’s plans called for “187 suites, with 506 rooms, 231 baths, and 385 toilet rooms.”

As construction neared completion, the Todds leased the property to hoteliers Anderson & Price for 21 years. It appears to be Anderson & Price who named the hotel. They additionally ran the newly-opened Mount Washington Hotel at Bretton Woods in the New Hampshire White Mountains.

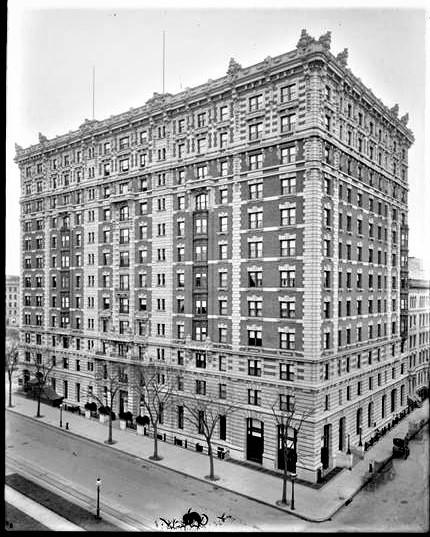

Completed in 1903, the Bretton Hall Hotel sat on a three-story base of rusticated stone. Nine floors of red brick, limestone and terra cotta rose to an elaborate iron cornice that sprouted frothy ornaments. Mulliken’s insertion of seven-story stretches of quoins and stone-faced bays gave the structure verticality and visually relieved the heavy mass.

The New-York Tribune commented on the behind-the-scenes technology necessary to operate the resident hotel. “The building has an electric plant, four engines, four boilers, four dynamos, a cold storage, laundry and kitchen plant.” The article added “It also has six elevators and a United States mail chute.”

Unlike transient hotels, resident hotels like Bretton Hall leased suites to long-term tenants. They enjoyed the amenities of a hotel–barber shop, dining room, maid, hallboy and messenger service, for instance–along with the relative permanence of an apartment building.

On November 1, 1904 Mrs. John Jay Tonkin of Oswego, New York, moved into a suite with her 11-year old daughter, Rosamond. The Evening Telegram explained that they were “driven from their luxurious home on Lake Ontario by dread the child would be stolen.”

John Tonkin was well-known as an iron manufacturer and philanthropist in Oswego. For more than two years his family had been terrorized by threats of Rosamond’s kidnapping and worse. The Evening Telegram said “It is believed the man is an artist, for many of the letters were illustrated with sketches of the girl and of the fate which it might be expected she would meet if she fell into the hands of her pursuers. Tortures and death by pistol and poison were pictured with such hideous vividness that they, as much as the threats, undermined the health of the fond mother.”

Even with Rosamond (whom The Evening Telegram described as “tall and well developed for her age”) and her mother now secretly ensconced in Bretton Hall, no chances were taken. The Tonkin coachman accompanied Rosamond to school on 70th Street near Riverside Drive. It was the only time she was permitted outside, “as she was kept indoors at other times through fear, and had become pale.”

Four months after Rosamond and her mother moved into their apartment, the threats had stopped. And so, in March 1905 “Rosamond was permitted to trundle a hoop on the sidewalk in front of Bretton Hall.” On each occasion the doorman, Charles Lytle, was instructed “to keep his eyes constantly upon her,” reported The Evening Telegram. But “Something called him into the house for a moment one day and when he returned to the sidewalk he saw the child in conversation with a man and walking near Eighty-sixth street.” Lytle ran after them, grabbing Rosamond, at which point the man rushed away.

Later Mrs. Tonkin received a letter demanding $50,000. The writer promised that if the money were not paid, Rosamond would be kidnapped. Instead, John Tonkin offered the $50,000–about $1.47 million today–to anyone who could identify the man. Handwriting experts were called in. With their whereabouts now known, Rosamond’s mother took her back to the family house in Oswego. Undeterred by the intensified hunt for him, the extortionist sent a new demand on June 8: “Dear Sir: Unless we have $100,000 before June 10 at noon we will take your Rosamond. You had better call off your detectives. Remember June 10 at 12. Mr. The Three.”

(As a side note, the threats eventually stopped and Rosamond was married to Ensign Forrest U. Lake of the U.S. Navy a decade later in 1914.)

On November 1, 1904 Mrs. John Jay Tonkin of Oswego, New York, moved into a suite with her 11-year old daughter, Rosamond. The Evening Telegram explained that they were “driven from their luxurious home on Lake Ontario by dread the child would be stolen.”

In the meantime, the meeting rooms of Bretton Hall were used by clubs and organizations. Only the well-to-do could afford automobiles and motor yachts and in November 1904 The New York Motor Club was formed in Bretton Hall. At its inaugural meeting on November 17, the purposes submitted by the Committee on Constitution and By-Laws were “to encourage the interest of motoring on land and water.”

But one member shouted out, “Why not add in the air?”

For years inventors had struggled to perfect a flying machine and, as a matter of fact, the Wright brothers had successfully flown their biplane for 59 seconds the previous December. The suggestion prompted a heated debate which, according to The New York Times, “waxed hotter and hotter.” Nevertheless before the meeting adjourned the purposes of the club had been amended to “promote motoring on land, water and in the air.”

A month later, early on the morning of December 14, 1904, the “engineer” (one of the staff tasked with minding the heavy equipment) went to the basement to “start the engines and dynamos,” as reported by The Evening Telegram. “He found the cellar filled with four feet of water. Barrels and boxes were floating about. Hundreds of dollars’ worth of machinery had been damaged.”

A large water main had broken and burst through the 86th Street subway station wall, “hurling aside the wall of the subway as if the bricks were merely chips of wood.” The flooded subway was crippled throughout most of the day and traffic was closed on Broadway until around 1:30. The Evening Telegram said “One of the places which suffered most was the big Bretton Hall apartment house.”

Residents looking forward to a warm breakfast that morning would be disappointed. The kitchen, also in the basement, was out of commission. But the inconvenience to the 175 families living here went much beyond that. “The hotel is without elevator service or electric lights and no heat can be supplied until the cellar is cleared. No meals can be served, and the patrons are forced to seek out refectories elsewhere.” And because four $5,000 boilers were destroyed, the entire building was without heat in the December cold.

Society women routinely gathered in the dining rooms of New York hotels for tea and luncheon. But they were unwelcome without a male escort after 6:00. At the dawn of the women’s rights movement, some well-to-women had had enough. One socialite complained to a reporter “To be sure, it might be that the man in the case was only a messenger boy brought in from the nearest telegraph office for the express purpose of complying with the letter of the law,” but being seated without “a mere man” was impossible.

To fight back the Equity Suffrage Club was formed in Bretton Hall in 1908. It was composed, according to one account, “of both men and women” and its first attack would be a boycott of those hotels following the system.

In February 1909 Anderson & Price purchased the hotel they had been leasing since its opening. In reporting on the deal, the New-York Tribune remarked “It is one of the largest exclusive apartment hotels in this city.”

For years the residents would appear in society columns and on the membership lists of exclusive clubs. Typical of them were Alden M. Young, the senior partner of Young & Warner and a director in two dozen corporations, and his wife. The Evening World called him “well known in club and fraternal circles, having been a member of the Union League Club, the Railroad Club, the Recess Club, and Odd Fellows and Royal Arcanum.”

The ballroom of the hotel was often the scene of society weddings, as well. On January 30, 1911, for instance, Eva Arnold, daughter of Standard Oil Company official Edward D. Arnold, was married to Earle Wayne Webb here. The New York Times mentioned “The presents, which numbered 250, filled three rooms of the first floor of the hotel.”

It was apparent the following year that Anderson & Price were now accepting some transient guests. And the arrivals on October 7, 1912, may have been a bit unnerving to strait-laced residents. The Sun reported “In splendid physical condition and confident of victory, the Red Sox arrived here from Boston at 6 o’clock last evening and went to Bretton Hall.”

Nevertheless, the long-term residents continued to be both well-heeled and well-known. Among them in 1913 was Henry L. Brittain, treasurer of the H. L. Brittain Company on Park Row. His ground-breaking firm manufactured “moving picture machines for the home.” He was also treasurer of the Granite Spring Water Company, the Anchor Metal Novelty Company and the Simplex Camera Company.

On January 2, 1913 the New-York Tribune reported on a significant turn of events for the wealthy businessman. He had traveled to Britain regarding the settlement of an estate. According to dispatches received by the Tribune from London, Brittain “was robbed of documents that related to an estate valued at $5,000,000.” Brittain told investigators he “does not expect to recover the lost documents which were stolen from his kit bag,” but offered a $250 reward, nevertheless.

Brittain was among the last of the long-term residents. Anderson & Price advertised Bretton Hall in 1914 as “New York City’s Largest Transient Uptown Hotel.” The ad touted “exceptionally large, quiet rooms with baths…All the comforts of the better New York Hotels at one-third less price.” A sketch of the building clearly showed that the cornice was still fully intact.

But two years later that condition was slightly different. An advertisement in the New-York Tribune on December 3, 1916 called the Hotel Bretton Hall the “largest and most attractive uptown hotel” with single rooms and a bath priced at $2.50 and $3 per day, and suites at $4 to $7.50. The most expensive accommodations would be about $177 in today’s money. But the photograph showed that cornice had been toned down, possibly in an attempt to keep the building looking up to date.

Despite the change from resident to transient, Bretton Hall continued to be a location for society weddings. Such was the case on June 26, 1916 when Esther Ford, the daughter of State Supreme Court Justice John Ford, was married to John Cassan Wait here. Ford had also served in the State Senate in 1895.

Well-dressed patrons were, perhaps, unaware of labor problems with the waiter’s union when they sat down in the Bretton Hall dining room on the evening of June 16, 1919. But Price & Anderson were well informed and prepared for problems. The New York Times reported that the 50 waiters, “stood at their posts, appraising the guests as they entered for the meal. According to one of the guests, there was an air of expectancy about part of the waiters, and this was explained when a whistle blew.”

Immediately upon hearing the whistle, the waiters formed a line and “with military precision departed.” The well-timed strike was planned to cause the most upheaval as possible. But Price & Anderson were well ahead of the potential disaster. The New York Times wrote “But just as the last of the strikers went through the door fifty substitute waiters came in another. So far as the guests were concerned the walkout merely served to show that most of the strikers had learned correct marching while in the service.”

A much more disturbing incident brought Bretton Hall back into the newspapers in November that year. Frank A. Skelton and his wife were residents of Montreal, but had taken rooms in Bretton Hall for the winter. On Saturday night, November 22 the couple went to the theater. When they returned about midnight, “they found everything topsy turvy,” said The New York Times. “Drawers from dressing tables, desks and bureaus were scattered on the tops of the tables, and clothing had been thrown upon the floor by the visitors in their search for jewels. Two jewel cases had been emptied and left open on one of the tables.”

The thieves were successful in their search. They had made off with “about thirty diamond rings, watches, necklaces and other valuable pieces of jewelry.” The loss was estimated at about $290,000 in today’s money. Mrs. Skelton refused to confirm that number, saying merely “Some of the pieces were so old as to be considered treasures; others were new, made of diamonds and platinum, and were of unusual design. The loss was heavy.”

Living in the hotel “in luxurious fashion,” according to The New York Herald, at the time was Mrs. May Jennings Bennett, a 32-year old widow widely known in religious circles. She was vice-president of the Women’s Foreign Missionary Society and was active in the work of the Fort Washington Presbyterian Church. And so it was most likely a great surprise to many when police knocked on her door on October 3, 1919 to arrest her.

Mrs. Jennings, through her church work, came in contact with many moneyed women. At teas or lunches in her Bretton Hall apartment she would mention that she was embarking on real estate projects–purchasing old houses in order to replace them with modern apartment buildings. After she had interested her victims in the potential, she would even take them to the see the properties, none of which she actually owned. She then collected thousands of dollars in “investment” from her unwitting dupes.

May Jennings’s defense was even more startling. When a journalist visited her jail cell on January 10, 1920, she said “I admit I played the part of a crook, but my downfall is due to the psychic divine control a man, formerly a Presbyterian minister, has had over me for the last year. That man conducts mystic ceremonies up near Central Park, and during all the time I was robbing my friends and acquaintances of thousands of dollars, I was under a spell cast over me by him.”

Her trial was held on January 21. She pleaded guilty and offered her curious explanation. Judge Mulqueen was not swayed. “I am convinced you are a common and base swindler,” he said before announcing her sentence of nine years in prison. When her lawyer pleaded for leniency, the judge reminded him that he could have imposed the maximum penalty of 40 years. “I think she is being treated leniently.”

In the early 1980’s an organization called the Artists Assistance Services took advantage of the low rents in Bretton Hall to scoop up apartments and offer them to “people in the arts.” New York Magazine cautioned, however, “But there was a little clause attached: The tenant had to share his living room with a ‘cultural activity.'” And so artist Abby Cahn shared hers with a karate class. That was a problem, she found out, when the karate instructor refused to let her have any furniture. And if classes were in session she was not allowed to enter.

An even bigger jewelry heist than the Skelton robbery happened two months later. Mr. and Mrs. Charles MacManus of Rye, New York, took rooms on the fourth floor here in the spring of 1920. On March 30 Mrs. McManus placed her jewelry in a trunk after dressing for luncheon. The following evening, when dressing for dinner, she found that someone had been in the trunk.

Missing were about 35 pieces of jewelry. Their total value, $30,000, would be equal to more than $375,000 today. The pieces were insured, unfortunately, for only about half their value. Ironically, the most valuable of the pieces had been in a safe deposit vault and had only been removed a few days earlier for appraisal.

The proprietors of the hotel embarked on a forward-thinking plan for its employees in February 1927–shared-cost benefits. The New York Times explained “The Hotel Bretton Hall joined its employes [sic] in the purchase of a $225,000 group life insurance policy from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.” More than 200 employees now not only had a life insurance policy, but an early form of health benefits. “The plan includes a visiting nurse service, distribution of health conservation pamphlets and provides for the payment of an employe’s [sic] insurance in full if he becomes totally and permanently disabled before the age of 60.”

In June 1929 the owners, Benjamin Winter, Inc., hired architects Springsteen & Goldhammer to make renovations, including converting the southern half of the street level to shops The New York Times noted that “remodeling of the interior of the 500-room structure is also under way.” The renovations resulted in 150 single rooms, 120 two-room suites, 25 three-room “apartments,” seven four-rooms suites and, along with the stores, a bar and restaurant.

In 1931 another store, much less architecturally invasive, was installed in the northern corner for The Chase National Bank.

The heyday for Bretton Hall seems to have passed by 1939 when a room cost $2.50 per night. It was a mere fraction of the amount charged in 1916.

In February 1950 the newly-formed Hotel Bretton Hall, Inc., headed by Grace Bordiga, purchased the structure. In reporting the sale, The New York Times noted “Improvements planned by the new operators…include plans for a dining room so that it can be used for catering purposes and the installation of kitchenettes in some additional apartments.”

While still offering 78 hotel rooms, the renovated Bretton Hall now included dentists offices and, on the second floor, the Rutledge Club and offices. Somewhat surprisingly, the building became a center of the Upper West Side Haitian community. Decades later, in 1993, Rev. Thomas Wenski, director of the Pierre Toussaint Haitian Catholic Center recalled to a New York Times reporter “Our community was centered on the West Side of Manhattan, mostly around 86th Street along Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue…A number of families managed to congregate at the Bretton Hall.”

The ballroom here was rented by campaign of Representative Bella Abzug to watch the election results of July 20, 1972. Although the 51-year old Congressional freshman had hoped to rally the feminist vote, she and her supporters were disappointed when it became obvious she had been unseated.

In the early 1980’s an organization called the Artists Assistance Services took advantage of the low rents in Bretton Hall to scoop up apartments and offer them to “people in the arts.” New York Magazine cautioned, however, “But there was a little clause attached: The tenant had to share his living room with a ‘cultural activity.'” And so artist Abby Cahn shared hers with a karate class. That was a problem, she found out, when the karate instructor refused to let her have any furniture. And if classes were in session she was not allowed to enter.

Emad Salem, living here in 1993, was a translator and bodyguard for Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, known commonly in the United States as “the Blind Sheikh.” Following the World Trade Center bombing that year, Salem made himself available to the F.B.I., who later said “Mr. Salem was central to the arrests of the accused plotters, luring them to make statements that were recorded, helping to test explosives and even renting the house in Jamaica, Queens, where the suspects are accused of mixing the fertilizer and fuel for the bombs.” With Salem’s assistance, the F.B.I. was able to wiretap that house.

Following the arrest of the sheikh and his cronies, Salem made a quick disappearance with Government help. On June 26 The New York Times wrote “Neighbors at the Bretton Hall residential hotel at 2350 Broadway, where Mr. Salem lived, said they saw garbage from his apartment at the trash chute on Wednesday, including a telephone that looked as if it had been ripped from a wall, and pictures of his son and daughter.” Salem’s information had also helped derail 12 other targets, “including Grand Central Terminal, the Empire State Building and Times Square,” said officials.

By now the entire cornice had been gone for years. The owners embarked on a renovation late in 2006 that initially called for reproducing the lost cornice. Architect John C. Calderón, however, found that “the cost was prohibitive.” Instead he designed a parapet of red brick and cast stone in an effort to approximate the lower design. Despite the good intentions, it falls short of a design-completing cornice.

The completed $1 million renovation resulted in 461 rental apartments.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

building database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses currently at 2350 Broadway:

Meet Sam Belanger!

Meet Andreas Davetas!