The Amidon

by Tom Miller

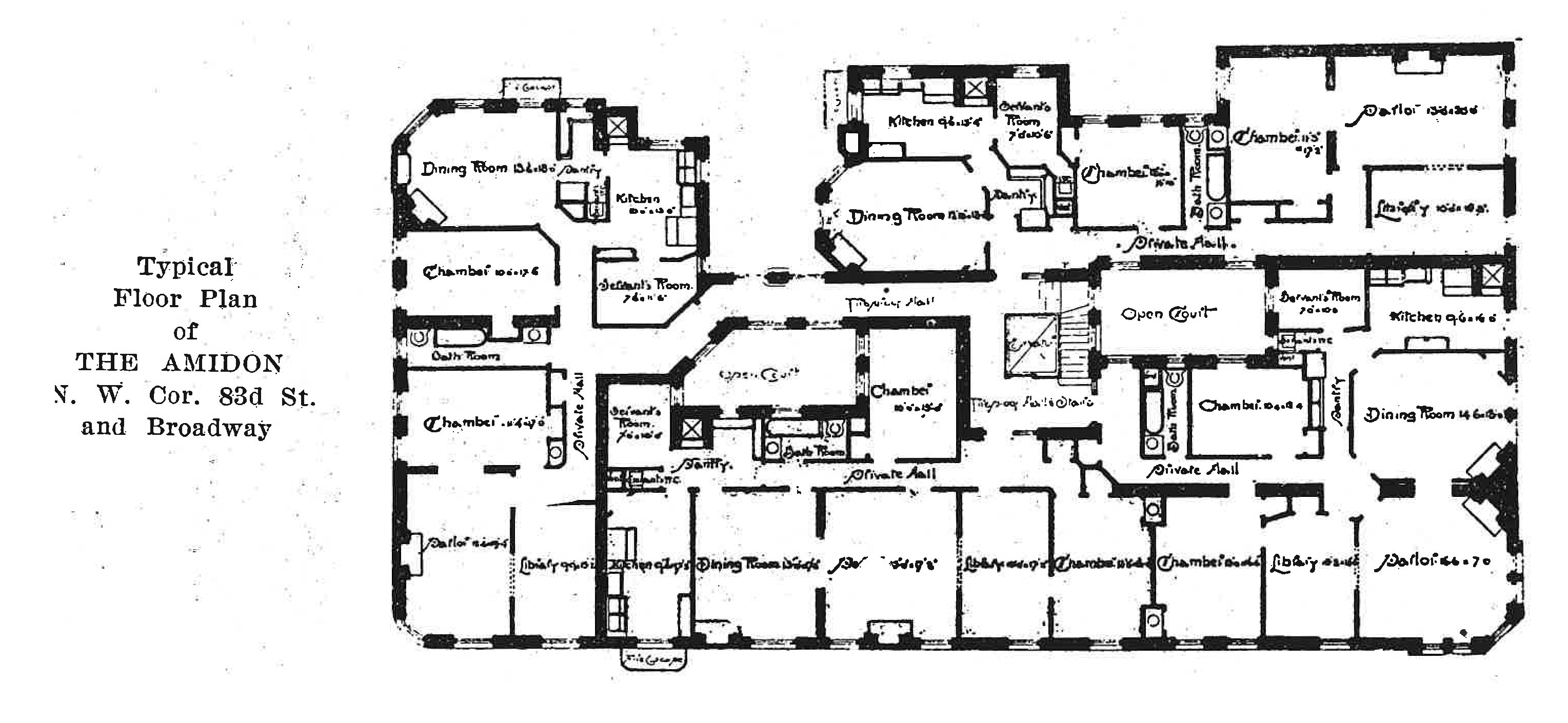

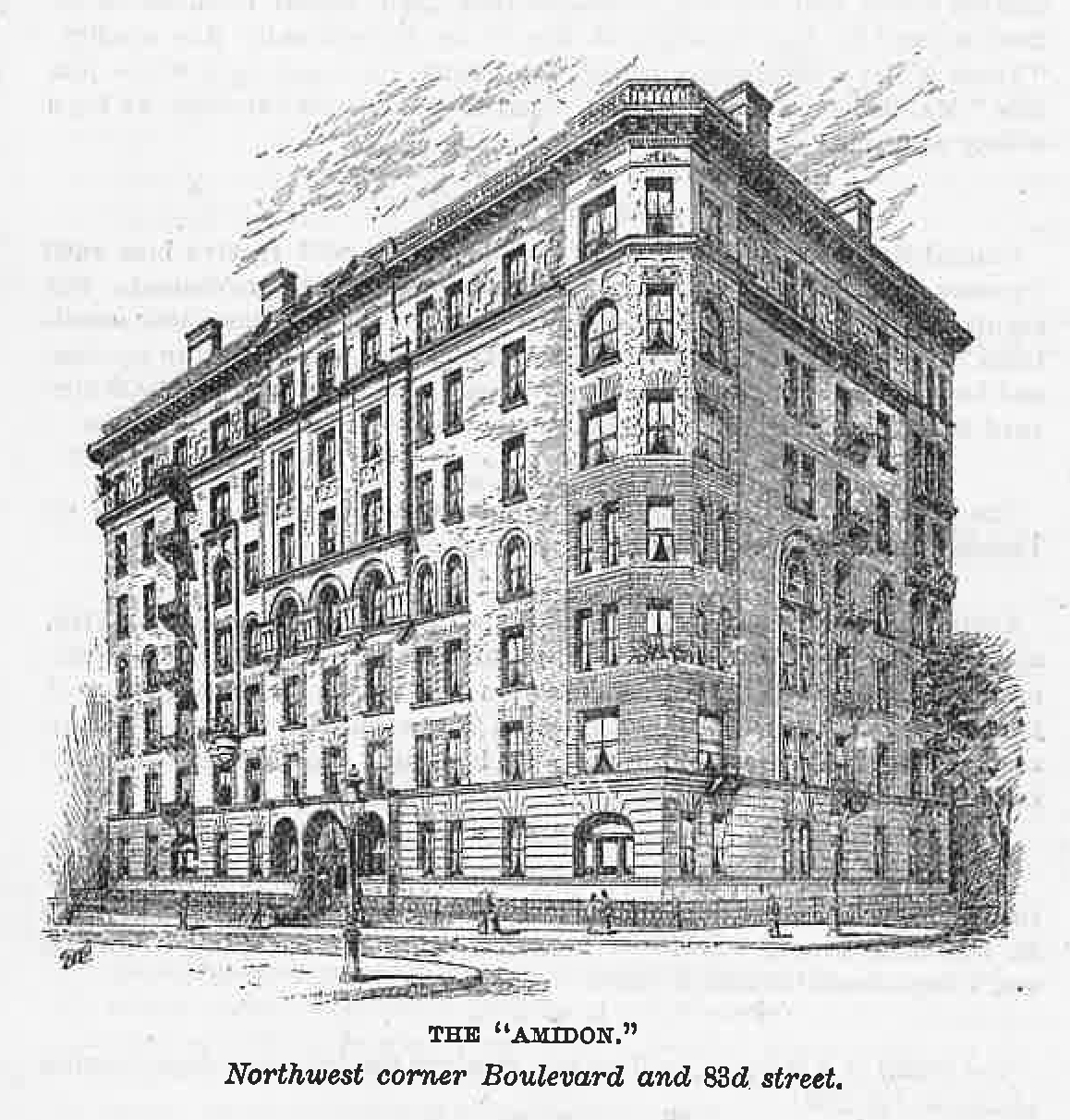

Real estate development was one profession in the late 19th century in which women (those women who had enough money and shrewd business sense) could compete shoulder-to-shoulder with men. One of them was Georgianna M. Amidon, who in 1891 hired architect Edward L. Angell to design a seven-story “flat and store” building on the northwest corner of Broadway and 83rd Street.

A mixture of Renaissance Revival and Romanesque Revival styles, the structure was completed in 1892 at a cost of around $6.75 million in today’s money. It was named The Amidon, after its builder and owner. Angell clad the upper floors in buff colored Roman brick liberally trimmed with terra cotta. The double-doored residential entrance, on West 83rd Street, sat snugly within a medieval-inspired arch supported by clustered colonnettes.

The seven-room apartments filled with financially comfortable residents, like stockbrokers Charles Knower Randall and Greenville A. Kissam, and attorney Albert H. Gleason.

In 1908 Averett L. Langdon, the traffic manager of the Long Island Railroad, his wife, Georgia, and their adult daughter Marguerite lived in The Amidon. Things between Averett and Georgia were not amicable. It reached a breaking point on September 29 that year when Averett obtained a warrant to have his wife arraigned before the West Side Court, claiming she was insane.

Marguerite accompanied her mother to the courthouse, where Georgia asserted, “I am not insane. My nerves have been shattered by the continued cruelty of my husband. He has tried several times to smother me with pillows, and only the intervention of my daughter saved me.” When the judge asked Marguerite if that was true, she answered, “That is true, your honor. I had to drag mother away from Mr. Langdon and take her to another room on one occasion.”

Why Langdon wanted his wife out of the way was, perhaps, explained in Georgia’s next statement to the judge. “Besides that, my husband has been keeping company with a young woman.” Nevertheless, according to The Sun, Georgia was “committed to Bellevue Hospital…for examination as to her sanity.” Marguerite insisted on accompanying her mother there in a cab.

Georgia, it seems, was deemed sane at Bellevue Hospital; however, the marriage did not last. Upon Averett’s death years later, the only family member to receive a bequest was their other daughter, Jessie, who had not been involved in the marital turmoil.

Also living in The Amidon at the time were Dr. Geza Kremer, his wife, Sophia, and their adopted son, Carleton. Kremer had worked for the City Department of Health since 1897. The Kremers had adopted 4-year-old Carleton on October 14, 1907, following the divorce of his parents, Forrest and Maud Clark. But Maud Clark soon regretted signing the papers.

Things between Averett and Georgia were not amicable. It reached a breaking point on September 29 that year when Averett obtained a warrant to have his wife arraigned before the West Side Court, claiming she was insane.

On the day that the Kremers brought the boy to The Amidon, his mother followed. She waited in ambush until he and his new aunt came outside. The New York Times reported, “Mrs. Clark came with a woman named May Bradley and hustled him into a cab before Miss Kremer, the doctor’s sister, who was present could stop them.”

The Kremers got the boy back “by legal proceedings” and everything was going happily until November 1908. Maud Clark kidnapped him again, hiding him at her mother’s home in Dorchester, Massachusetts. The Kremers put private detectives on the job and eight months later, on July 1, 1909, Sophia received word from Boston “that she had better come at once, as there would be a good chance to recover the boy on Friday, the next day, owing to the watch over him being somewhat relaxed,” as reported by The New York Times on July 4.

Sophia and four private detectives drove to the grandmother’s home “in a carriage with a very fast horse.” Two of the detectives went to the front door and knocked, to distract the occupants. Sophia and the two other men went to the rear of the house and entered. She found Carleton playing alone. The New York Times said, “She seized him in her arms and rushed to the carriage, which drove off at a fast pace before the inmates of the house realized what had happened.” Instead of bringing him back to The Amidon, Sophia took him to the Kremer’s summer home in the Adirondacks, then telephoned Dr. Kremer to meet them there. The New York Times noted, “The seizure of the boy at Dorchester on Friday created considerable excitement there.”

Maud Clark was, however, relentless. On December 27, 1909, Carleton was outside tossing snowballs when she suddenly appeared, grabbed him, and headed for a taxicab waiting on Broadway. Carlton began screaming, “I’m being kidnapped!” His cries caught the attention of a patrolman who intervened. At the station house the boy told Lieutenant Austin that he was being carried off against his will. “My name is Carlton Kremer. I live at 233 West Eighty-third street.”

Maud told the officer that she was the boy’s mother, to which Carlton responded, “You used to be, but you are not anymore.” The lieutenant called the Kremers and Sophia came to bring the boy home. She refused to press charges, saying that “it was only natural for Mrs. Clark to care for her own boy, but that Carlton is perfectly satisfied to remain where he is.”

But then, almost unbelievably, the Kremers had a change of heart. The following day The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “Moved by the pleadings of Mrs. Maud Clark, the mother of 6-year-old Carlton Clark, who was adopted five [sic] years ago by Dr. and Mrs. G. Kremer…the foster parents of the child restored him to his mother after she had kidnapped him last night as he was snowballing in front of his home.” Maud told the reporter, “I know he was happy with them, but my mother love was too great to have him away from me.”

Now childless, the Kremers focused on other things. Sophia became a leading suffragist in New York City. On June 19, 1914, the New York Herald wrote, “Among these defiant and almost militant suffragists are Mrs. Sophia Kremer, of No. 233 West Eighty-third street, who is president of the Victory 1915 Suffrage Club.”

The group organized a lawn fete to be held in Central Park on June 20, 1914, and passed out tickets to the children in public schools on the Upper West Side. When Laura Charlton, the principal of Public School No. 93 found out about it, she demanded that the students give her the tickets, which she tore up. She told them, “If these women return again, I shall cause their arrest.” In response, said the New York Herald, “Mrs. Kremer announced last night that Miss Dollie Trafton would lead a delegation to the school and demand to be arrested.”

In May 1918, Dr. Geza Kremer was appointed the medical superintendent of Sea View Hospital on Staten Island. In reporting on the appointment, the New-York Tribune noted, “The War Department is now negotiating with the city for the taking over of Sea View Hospital as a base hospital.”

By then, The Amidon was home to several tenants in the entertainment industry. Among them were playwright and screenwriter Channing Pollock, and his wife, playwright and press agent Anna Marble Pollock. Also living here in 1920 were producer F. Ray Comstock, and stage and film actress Edith Taliaferro, and her husband actor Earl Browne.

At the time the Levy Brothers stationery store occupied 2305 Broadway and would be a fixture in the neighborhood well into the 1940’s. It was the scene of a bizarre burglary on December 22, 1938. Hyman Boston opened the store at 5:00 that morning, turned on the lights and took off his overcoat and hat. Just as the 48-year-old went behind the counter, “a bandit stepped out of hiding, jabbed a pistol into his ribs and ordered him to the rear,” reported The New York Post.

Once in the back room, the burglar ordered Boston to remove his trousers. He then took $21 from the pocket and tossed them to the floor. “Now the shirt!” he ordered. The article said, “Boston hesitated—for it was cold in the store and, after all, there’s a limit. But the pistol prodded his side impatiently and off came the shirt.” The robber then ripped the shirt into strips of fabric which he used to bind and gag Boston. He escaped with an additional $80 from the cash register. It took the clerk half an hour to free himself. Police discovered the burglar had gotten in through a skylight.

Mary Bobb lived in the Amidon in 1931 while, unknown to her husband, she carried on a romantic affair with a Japanese doctor on East 80th Street. Mary was comfortable with being unfaithful to her husband, but she was not comfortable with Dr. Sabro Emy’s being unfaithful to her. She hid in the hallway outside his fifth-floor apartment on October 29 until she saw another woman enter. Mary rushed in, armed with a hammer. When the commotion brought police, she jumped out the window to escape. The plan did not work, and she was arrested.

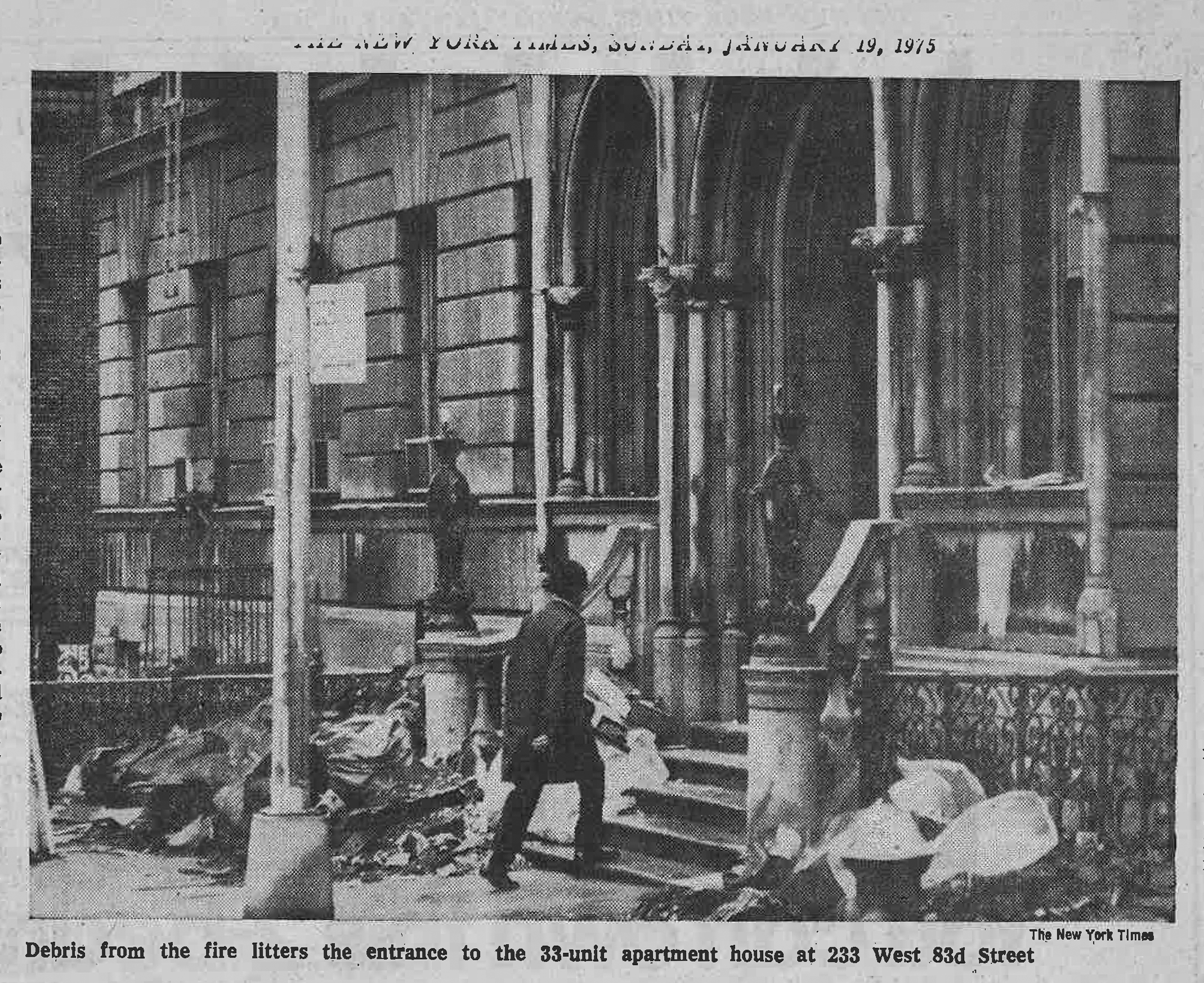

Thirteen firemen, nine residents, and a policeman and a mailman who helped rouse the tenants suffered injuries. The entire top floor and roof were destroyed.

Living on the seventh floor in 1974 was writer Evert Fulton. He was working on a manuscript on December 20, when he paused to refill a cigarette lighter. The lighter fluid spilled onto the sofa and onto the manuscript. When he lit the lighter, the sofa and the papers ignited. Fulton ran to the hallway for a fire extinguisher. By the time he returned, his apartment was “a mass of flames.”

Fulton fled and the fire spread through the seventh floor, growing in intensity to a five-alarm fire. The New York Times reported that it “burned out of control for three hours…As 195 firemen battled the flames, cornices and sections of the roof broke off from the building and fell with a roar to the sidewalks of Broadway and 83rd Street, showering parked automobiles with hot bricks and drawing gasps from the hundreds of onlookers.” Thirteen firemen, nine residents, and a policeman and a mailman who helped rouse tenants suffered injuries. The entire top floor and roof were destroyed.

The owner, Walter Scott & Co., Inc. initiated repairs. The firm apparently took advantage of the sudden evacuation to redo the floor plans. The renovations resulted in five apartments per floor above the first floor. Sadly, no attempt to replace the cornice was made.

Artist and sculptor G. Augustine Lynas moved into the building in 1978. In 1992, when the building turned 100 years old, he began giving it what he called “a little bit of a face lift.” He first refinished the century-old oak entrance doors and cleaned the transom above them which reads, “Amidon.” On June 18, 1995 Robin Pogrebin, writing in The New York Times, said he then “started creating what he calls, ‘spontaneous sculpture.’” Lynas replaced the capitals of Edward L. Angell’s colonnettes with faces and figures. On one side were historical portraits: Ghandi, Lincoln, Mother Teresa, Mark Twain, Nelson Mandela and Helen Keller. On the other were endangered or extinct animals like the Indian elephant and the white rhinoceros.

The somewhat quirky sculptures remain, adding to the already somewhat quirky architecture of the Amidon.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 233 West 83rd Street:

Meet Neena Chopra!