2310-2318 Broadway aka 210 West 84th Street

by Tom Miller

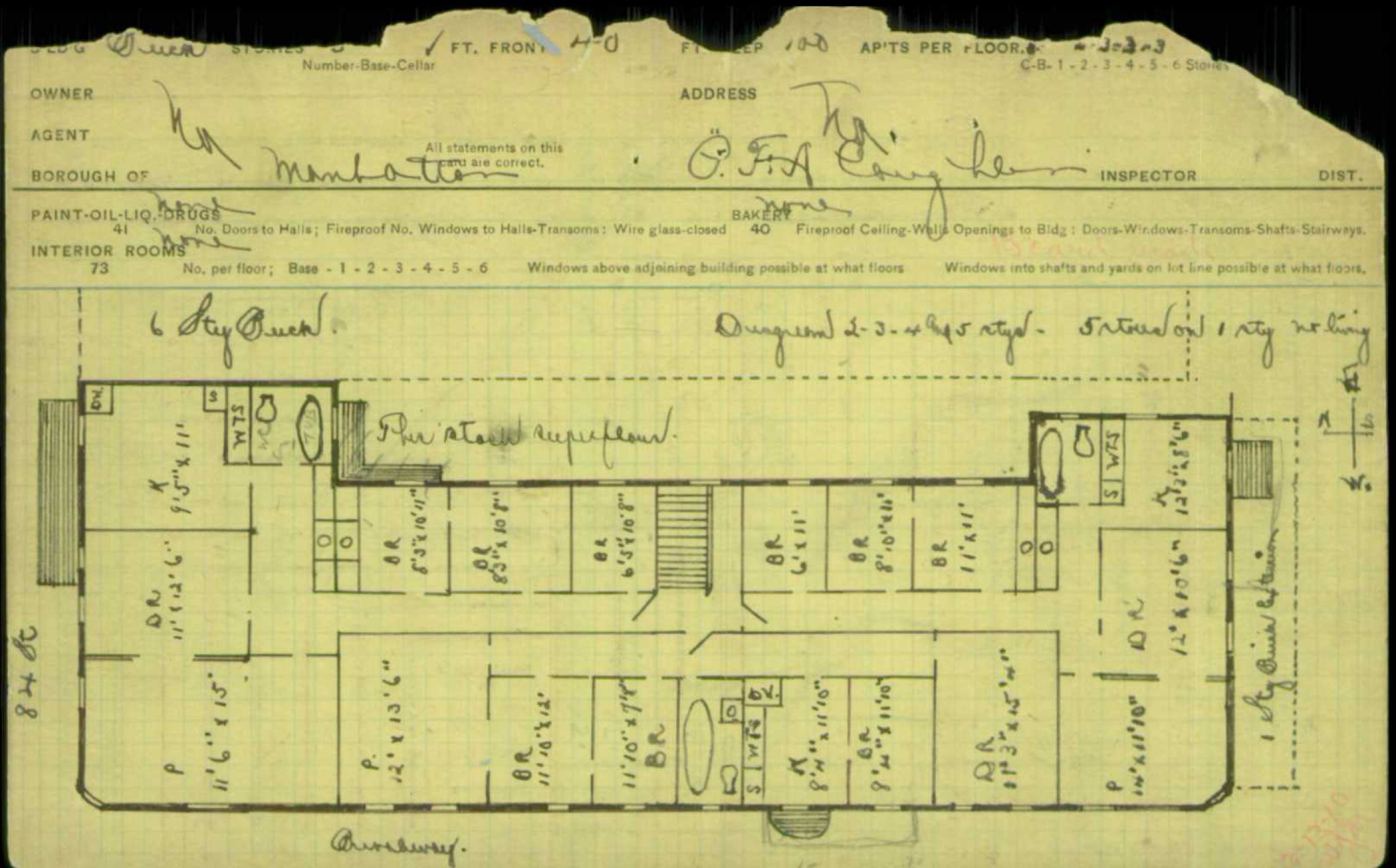

In 1901 a five-story brick-and-stone apartment building was completed on the southeast corner of Broadway and West 84th Street. Designed by Alfred H. Taylor for Charlotte E. H. Fountain, it was a successful marriage of Romanesque Revival, neo-Grec, and Renaissance Revival styles. Stores lined the Broadway side, while residents entered around the corner at 210 West 84th Street.

Almost immediately, tenants’ names appeared in newsprint for the wrong reasons. The first was William G. Miller, who listed his profession as a salesman, but who had a far more profitable sideline. He and stockbroker John W. Smith ran a crooked roulette game on West 27th Street in the notorious Tenderloin District. And the way they lured their victims was more than devious.

In March 1902, Miller ran into an old acquaintance, Henry W. Poster, in the Rossmore Hotel. On March 21, the New-York Daily Tribune reported, “Poster says he has known Miller for twenty years as a man of character and respectability.” The two began talking, and Miller said he had developed a system of beating roulette. “He did not want any money, he said, but had a grudge against a man who ran a roulette wheel, and, according to Poster’s complaint, if Poster would play his system, he would be satisfied if Poster won,” said the article. Miller told Poster that seeing his nemesis lose money was enough gratification for him.

He took Poster to the West 27th Street house where Smith was manning the roulette wheel. Within two hours, Poster had lost $2,000—the staggering equivalent of $65,000 in 2023. The newspaper reported, “the other men expressed sorrow for him and promised to meet him later at the Westminster Hotel and show him a way of getting his money back.” Poster promised to do so, but instead went to the police. The New York Press reported that he told Captain Sheehan “he had been made the victim of ‘brace’ gambling, known as the ‘big mit’ game.”

He and stockbroker John W. Smith ran a crooked roulette game on West 27th Street in the notorious Tenderloin District.

But as it turned out, Poster lost his money and Miller and Smith went free. In court Poster told his story to Magistrate Deuel, who asked “if he had not tried to beat the game,” according to The Evening Post.

“Yes,” Posten replied.

“Well, the law can’t do anything for you,” said Deuel, and ordered the defendants discharged.

At the time George W. Hill, his wife Annie Priscilla, and their grown son Willis shared an apartment here. George was described by The World as “the deaf janitor of the Ninth Regiment Armory, and who for thirty-five years was drum-major of the regiment.” Willis R. Hill was a clerk in the Health Department.

One day George’s aged, unmarried uncle, Isaac Cassell, appeared at the apartment. The World said the old man was “alone and practically friendless…and told his nephew that he was without a dollar and asked for shelter. The deaf nephew told him that he was as welcome as the flowers in spring and that he should make his home there.”

It turned out to be a ruse. Cassell wanted to make sure his nephew was deserving of an inheritance. The World said, “he was quite wealthy and said that he wished to make a will leaving his property to Hill’s wife.” The will was drawn up on August 1, 1903, with Willis Hill appointed executor.

Isaac Cassell died four months later. Annie Priscilla Hill was notified that his estate entailed $1.04 cash and a gold watch. Suspicious, Annie did some investigating and discovered that Cassell had changed attorneys a month after his will was written. The deed to his house, worth $7,000, had been transferred to his new lawyer. Moreover, “The Masonic friends of Cassell in Middletown [New Jersey] say that Cassell must have been worth at least $20,000 and probably more,” said The World. The newspaper reported on December 22 that Annie and Willis, “suspecting that in his old age, her husband’s uncle had been swindled of his fortune,” were headed to Middletown to get to the bottom of things.

Another resident to appear in the newspapers that year was Julia Thorpe. The 25-year-old and her accomplice Cora Harris made a living in a most unladylike way. Julia would “loiter” on the street, a term police used to describe prostitutes luring clients. Whether she was truly a prostitute is unclear. In either case, while she engaged a man in conversation, Cora would pick his pocket.

Unfortunately for the pair, undercover detectives Dukeshire and Rice were on to them. On October 21, 1903, Dukeshire approached Julia. Attached to his gold watch chain was a diamond locket. Rice watched from nearby and later told a judge that while Dukeshire “was talking to the Thorpe woman he saw the Harris woman snatch the locket from the chain hanging to his partner’s watch.”

The World reported, “Detective Dukeshire said that he knew all the time that the woman was trying to rob him, and he let her go as far as she like, but he did not think that she would be so bold as to break his chain.” Julia Thorpe was fined $10 for loitering, and Cora Harris was arrested for attempted robbery.

The store at 2312 Broadway was home to Cullen & Karas tire store by 1905. It would remain for nearly two decades. Most likely, one of the shop’s customers was contractor T. W. Wood, who lived on the fourth floor. On the afternoon of July 10, 1911, the Woods’ chauffeur dropped Wood and his wife off at the curb. The couple had just entered their apartment when they heard a horrific crash.

Cab driver Oscar Bruen had picked up a couple at the Cunard steamship docks. As he approached Broadway and 84th Street, the bolt in the steering gear broke and the taxi crashed into the rear of the Woods’ touring car. The New-York Tribune reported, “the gasoline [sic] tank of the touring car burst when his cab struck it.” The male passenger was cut with flying glass, and his companion fainted. The article said, “Mr. Wood and his wife saw [their] $6,000 machine burn from a window on the fourth floor.”

As he approached Broadway and 84th Street, the bolt in the steering gear broke and the taxi crashed into the rear of the Woods’ touring car.

Cullen & Karas Tires went bankrupt in 1922. At the time, 2314 Broadway was home to Madame La Stelle’s lingerie shop. In February that year, she advertised, “corsets, brassieres, made to order; also cleaned, altered and copied at short notice.” For her shyer feminine customers, the ad promised Madame La Stelle “will call at your residence.”

Another resident who found himself on the wrong side of the law was 28-year-old William Doyle. On May 11, 1928, the Daily Argus reported, “Choosing the heart of the theatrical district as the locale for a robbery, a daring bandit today blackjacked a girl bank messenger in the Paramount building, 44th street and Broadway and fled.”

The daring bandit was Doyle. He had apparently watched the movements of 26-year-old Katherine McNey for a few weeks. She was the cashier in the Walgreen drugstore in the Paramount building. There was a Chemical National Bank branch on the third floor, so taking a cash deposit from the store to the bank should have been safe. But as Katherine stepped from the stairway into the hall on the third floor, Doyle hit her on the head with a blackjack and grabbed the money. He did not get far. Two detectives chased him for less than a block, and he was arrested in front of the Astor Hotel, “while blasé Broadwayites gasped at his audacity in staging a holdup on the Rialto,” said the newspaper.

When the building was sold in 1941, it was described as having 14 apartments and four stores. The broad array of commercial tenants was evidenced in the 1970s when shops like Fun Fabrics, A Show of Hands (a crafts store), and Broadway Fish occupied spaces.

But it was all about to change. The building was demolished in 1982 to be replaced by an apartment building/movie theater designed by Held & Rubin.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 2310-2318 Broadway: