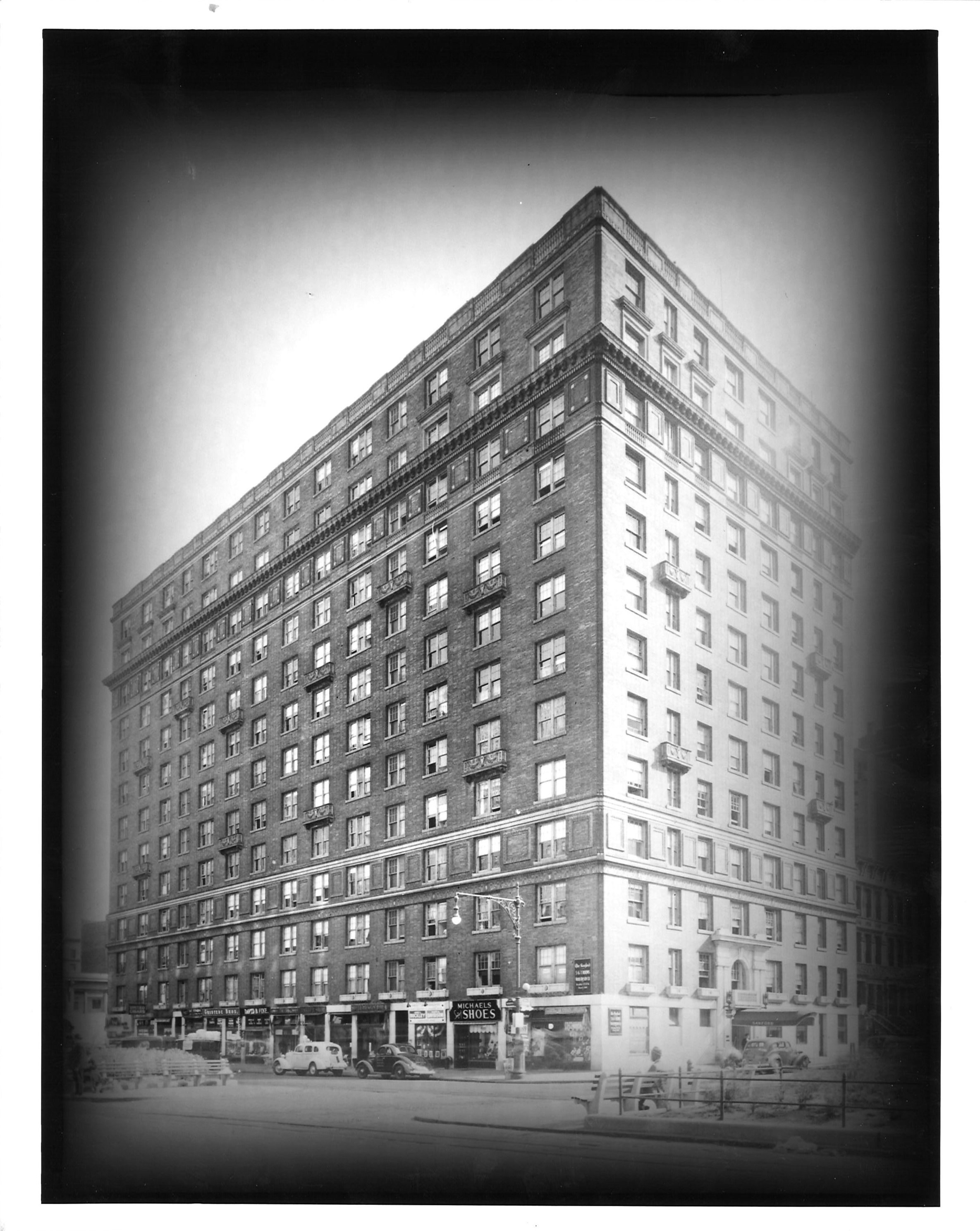

The Sanford and The Rexford Apartments

by Tom Miller

In May 1913 Paterno Brothers, Inc. acquired the blockfront on the east side of Broadway, between 78th and 79th Streets from Harry Barnes Newberry and Alfred Barnes. Designed by the firm Schwartz & Gross, the twin 12-story apartment buildings were completed in September 1914.

Ajello’s no-nonsense, tripartite Renaissance Revival style design incorporated little ornamentation. The back-to-back buildings pretended to be a single structure, heightening the overall blocky appearance. Stores lined the Broadway sides, while residents entered the Sanford at 229 West 78th Street and the Rexford at 230 West 79th Street.

On September 17, 1914, just prior to the buildings’ openings, The New York Times reported, “Each building contains suites for fifty families and on the ground floor are seven stores, most of which have already been rented.” The newspaper said that Paterno Brothers had invested $2.5 million in the project, including the land—the equivalent of $66.8 million today.

From the beginning, the well-to-do residents of both buildings appeared in newspapers for reasons other than receptions, weddings, and dinner parties. Among the initial residents of the Rexford was Laura Baird, the widow of a wealthy London manufacturer. In September 1914 she sought the services of Dr. Maurice Sturm, whom The New York Times said had “gained notoriety” for his “’turtle cure’ for consumption.”

The New York Times, on November 26, said that Laura “turned over to him her stocks and jewelry—at his suggestion, she says—when the physician explained that the valuables would be much safer if left with him.” The jewelry alone was valued at more than half a million in today’s dollars. When the treatments were completed, Laura Baird went back to Sturm’s office to retrieve her valuables, but he refused to relinquish them. “I was met by a storm of abuse,” she told police. Things got worse when she went to the telephone to call her attorney. According to Laura, the doctor flew into a rage. “He picked up a carafe from the table and hit me over the head with it. I fell, and as I struggled to my feet, he struck me again, crushing my nose. He also struck me with his fists.”

Laura went straight to the police station and filed a complaint. The New York Times reported, “The detectives said that the office was wrecked. Dr. Sturm said last night that he would not return Miss Baird’s jewels until he was paid in full for the treatment.” He changed his mind after spending “an uncomfortable night locked up in the West Sixty-eighth Street Police Station.”

The New York Times, on November 26, said that Laura “turned over to him her stocks and jewelry—at his suggestion, she says—when the physician explained that the valuables would be much safer if left with him.”

The next day in court he told the judge that he had held onto the valuables because “she was in no condition to receive them. But I’m ready to return them now.” Escorted by two detectives, he went back to his office and returned with a trove of stocks, cash, and jewelry, including “a $10,000 pearl necklace, two diamond bracelets, a diamond necklace,” and more.

Another Rexford resident whose jewelry ended up in the newspapers was Mrs. William L. Sherrill. She entrusted her son, Jack with an unset pearl, which was a family heirloom, a diamond, and a ruby in May 1916. The gems were valued at nearly $300,000 by today’s standards. He was to take them to the Chicago jewelers Spaulding & Co. to have them set.

But on March 6, when Jack stepped off the Twentieth Century Limited in Chicago, he did not go directly to Spaulding & Co. He met some old friends and later told reporter from The Chicago Tribune, “there was a party and some wine, and I forgot all about the jewels. Fact.” He further explained:

I had lunch at the College Inn, and later went to see ‘Chin Chin.’ Not bad at all. Then we had supper and some wine. Food not bad in this town. Not at all. But when I got home I found the chamois bag with the jewels gone.

Sherrill placed an advertisement in The Chicago Tribune offering a $2,000 reward for the return of the jewels. He said that he had telegraphed his father who was on the way to Chicago to help in the search. (One can imagine how the initial father-and-son meeting went.)

At the time of Jack Sherrill’s bungling, actress Georgie O’Ramey lived in the Rexford. She was appearing in Around the Man at the New Amsterdam Theater that year. And on the tenth floor was Otto Goritz, a grand opera singer. In April 1916 he was appearing in Boston while a nationwide search was going on for terrorists who conspired to dynamite the Cunard liner Pannonia. On April 3, The New York Press reported, “One was found hiding in a closet in the apartment of Offo Goritz, an opera singer, in No. 230 West Seventy-ninth street, where he had been visiting Elsie Alff, a maid.”

Young men from both buildings fought for their country in World War I. The family of William Herbert Smith, vice-president of the lithograph firm Zicograph Company, lived in the Sanford. Their 25-year-old son, Herbert, was a broker with the firm of Herrick & Bennett until he sailed for France in the summer of 1917. Herbert sent a letter from the front in July 1918 saying he had made a flight over the German lines but had to return “because the enemy got his range.” Soon after receiving the letter, the Smiths got word that their son was missing in action. And then, on August 4, the New-York Tribune reported, “Lieutenant Herbert D. Smith, of the air service, who was listed as missing in action, is a prisoner in Germany.”

Also leaving for the war were Eugene W. Percy and A. C. Berton, both of whom lived in the Rexford. On October 28, 1918, Percy, who was with the ambulance corps in France, wrote to his parents. It was an uplifting letter, which said in part:

We’re driving the Germans before us like cattle. Before we are through, we’ll show them how to take a joke. God, what a desert they’ve left! I guess the whole thing will be over soon.

The Evening Telegram commented, “To prove how optimistic the Americans were over the expected end of the conflict, Percy in his letter asks that money be sent him [by] Christmas so that he can ‘celebrate Christmas and the end of the war at the same time.’”

Percy was right. Four months later, on February 23, 1919, the New York Herald reported on the 10,000 soldiers aboard five troopships who had returned to New York City. The article noted, “Sergeant A. C. Berton, of No. 230 West Seventy-ninth street, was with the 331sst Tank battalion and came out of the war without a scratch.” But not all of those serving in Europe were men. A month after Berton came home, Mary A. Heaton, another Rexford resident returned. The New York Herald said she had been with a unit of the American Red Cross “and has been stationed at Neuilly for the last six months.”

A crime committed in the Sanford in the spring of 1920 proved to be a source of embarrassment for several society ladies. Mrs. Chester M. Curry, described by The New York Times as “the wife of a wealthy rubber importer,” had several women over on May 14. Mrs. J. C. Gleason, whom Mrs. Curry had met casually only once and who had not been invited, showed up. Mrs. Gleason was, reportedly, the widow of a Chicago banker who had died in 1913.

At one point during the evening, Mrs. Gleason excused herself to “powder her nose.” Her movements were not carefully watched by anyone since they were otherwise distracted. The women were playing poker and gambling. But at the end of the evening, Mrs. Curry discovered that a diamond bar pin, valued at $1,800, and her purse were gone.

Detectives went to the Pennsylvania Hotel, only to find that Mrs. Gleason and her mother, had gone. They were tracked down in Atlantic City where Mrs. Gleason admitted to taking the pin and turned it over to the detectives. But she claimed that she had been cheated in the card game and that she had merely found the pin on the bathroom floor and taken it as repayment.

Authorities did not buy her story. Police said that “they had evidence that she had stolen upward of $12,000 from other socially prominent families in this city within the last two months.” In court on June 9, Assistant District Attorney John Hogan declared, “this woman is a female raffles, and I demand that she be held in $15,000 bail.”

The problem for the respectable women witnesses was that they had to publicly admit, under oath, that they had been gambling.

Ben Fran…who has been seven times around the world. He has made five trips to Iceland and five Mediterranean trips, and has traveled more than half a million miles.” The newspaper noted, “He has returned only to prepare for another ‘round-the-world-trip, he said.”

A very colorful resident of the Sanford was Ben Fran, a retired businessman whose great passion was travel. On June 2, 1925, the Standard Union reported that the Cunard liner Franconia had arrived in port. Among its passengers, said the article, “the one boasting the greatest traveling record was Ben Fran…who has been seven times around the world. He has made five trips to Iceland and five Mediterranean trips, and has traveled more than half a million miles.” The newspaper noted, “He has returned only to prepare for another ‘round-the-world-trip, he said.”

Seven years later, on December 31, 1936, The Niagara Falls Gazette took up the story. “New York City serves only as a convenient jumping-off place for one of her native sons whose globe-girdling exploits rival those of Julius Brittlebank, the 77-year-old ‘American Marco Polo’ who recently completed his seventeenth round-the-world jaunt.” The article said, “In a set of half a dozen address books [Ben Fran] has lists of acquaintances in such diverse spots as Bali, Paris, Colombo, Cairo and Palm Beach. He sent more than 500 Christmas cards to his polyglot ‘pals’ recently.”

The Great Depression hit some New Yorkers harder than others. Phillip Weiss was a manager of the Equity Ticket Agency. The 37-year-old lived with his wife and two children in a seventh-floor apartment in the Rexford in 1933. With money tight, Americans cut back on unnecessary expenses—like the theater. On October 23 the maid, Nellie Sullivan, reported to work. She walked into the kitchen to find Philip Weiss hanging from a door transom. He had been dead several hours. Weiss’s wife told police that “he had been worried by financial difficulties.”

Throughout the subsequent decades, both buildings were home to several prestigious residents. Joseph Greenbaum lived in the Rexford until his death in September 1946 at the age of 80. A proofreader for The New York Times for more than three decades, he was considered one of the best in his profession.

Dr. Emanuel Gamoran, a leader in Reform Jewish education in the United States, lived in the Sanford in the 1950’s and early ‘60’s. The New York Times said he was credited “with having revolutionized the curriculums and techniques of Jewish religious education in this country.”

Another resident of the Sanford was Samuel Liss, senior economist with the Farm Security Administration during the Franklin Roosevelt Administration. He and his wife, Theresa Kovner, maintained a summer home in East Hampton, Long Island.

Today there are still just four apartments per floor in the buildings. Other than the shop fronts along Broadway, almost nothing has changed in the appearance of the Sanford and Rexford.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses at 2200 Broadway:

Meet Gina Kim!

Meet Carlos Chuva!

Meet Nichole Sesti and Nick Sparacio!