The Borchardt

by Tom Miller

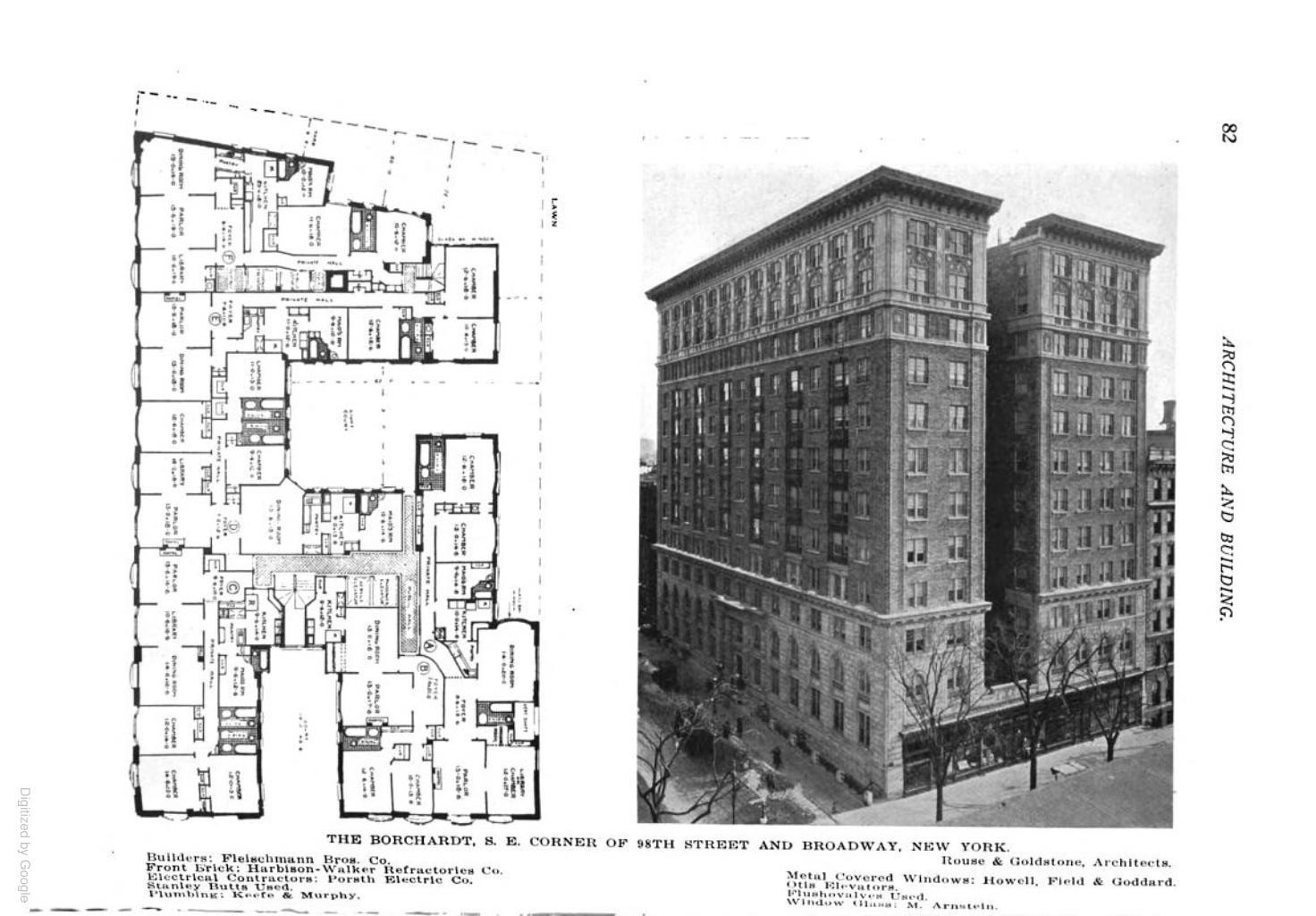

In his 1912 The Book of New York, Julius Chambers said that the apartment houses erected by Samuel Borchardt “in architectural design and elegance of interior surpass any buildings of the like character in the metropolis. Especially is this the case with ‘The Borchardt’ at 98th Street and Broadway.” Chambers deemed The Borchardt “the most beautiful apartment on Broadway.”

Two years earlier Borchardt had hired the architectural firm of Rouse & Goldstone to design the 12-story structure, which cost the equivalent of $29.4 million in 2023 to construct. Completed in 1911, it housed 75 well-to-do families. Deep light courts carved into the brick-and-stone mass of the building guaranteed natural light and ventilation to all the apartments. Along the Broadway side were shops, one of which was the ladies clothing store of George W. Leavy. Another became the offices of Samuel Borchardt’s real estate business.

The residents held white-collar jobs, like Guy Phillips who was assistant secretary of the Missouri Pacific Railway Company; and Frank J. E. Fitzpatrick, office manager of the banking firm L. F. Dommerich & Company. The names of the female residents appeared frequently in the society columns, as was the case on November 5, 1912, when the Newark Evening Star reported, “Mrs. Stewart Hathaway will receive on Friday and Saturday of this week from 4 to 7 o’clock at her home, 220 West Ninety-eighth street, New York.”

Frank J. E. Fitzpatrick and his wife Alice had two daughters, Milreal and Azelda who were 6 and 13 years old, respectively, in 1912. The girls were seen little at the Borchardt, since they spent their school terms at a boarding school. That year Alice began suffering acute depression that became so serious that in September 1913 she attempted suicide by swallowing bichloride of mercury. She was saved by the fast action of a doctor and committed to a sanitarium where she seemed to recover both physically and emotionally.

Nonetheless, when Alice returned to the Borchardt Frank hired a full-time nurse. At 5:00 on the evening of November 3, 1913, Alice said she was going to buy cakes at a bakery on Amsterdam Avenue between 97th and 98th Streets. Frank later explained, “She was in such good spirits that she said she didn’t want the nurse to go with her. I didn’t object and she left the house. After about an hour passed and she did not come back, I began to be alarmed.”

“She was in such good spirits that she said she didn’t want the nurse to go with her…”

The nurse went to the bakery where she was told Mrs. Fitzpatrick had purchased “some trifles” and left “in the best of spirits.” But four days later Alice was still missing and a general police alarm—today known as an all-points bulletin—was issued. On November 7 The Evening Enterprise noted, “Two daughters are at a convent school and do not know that their mother is missing.”

More than a week after Alice Fitzpatrick left the apartment, the New York Press titled an article, “Banker’s Missing Wife Found Half Starved.” Her husband answered the telephone at 8:00 on November 10 to hear his wife feebly say she was in Saunders’s restaurant in Brooklyn. He told her to wait there, and rushed to the eatery. The article said, “Mrs. Fitzpatrick told an incoherent story of her wanderings since her disappearance. Her condition forbade much questioning.” In her pocketbook was most of the $5 she had left the apartment with, and she was adamant that she had spent most of the time at the family’s former home in Brooklyn. (Police had checked that address several times throughout the week.) Describing her as “emaciated and almost starved,” the newspaper said, “She is under the care of a physician.”

Dr. David W. Tovey and his wife, Blanche, lived in the Borchardt at the time. He was a member of the faculty of the Polyclinic Hospital. It appears that Dr. Tovey had had an extra-marital fling, one which threatened to cause him scandal or financial problems. Two women, Alice Harding and Elizabeth Ferguson, made several visits to him at the Polyclinic Hospital, and then showed up at the apartment demanding money. Blanche not only overheard the conversation between them and her husband, but when he was out of the room, heard one woman say, “We can easily get rid of the wife. We got rid of the other women. This ought to be worth $1,000. When you get through with him, I’ll get more money out of him.”

Knowing that Alice Harding had an appointment with her husband, Blanche went to the hospital and intercepted her and Elizabeth Ferguson. She later explained that Elizabeth “told her a story and threatened to tell it to others if the money was not paid.” She told officials, “I told the girls to do nothing, that I, not Dr. Tovey, would pay the money.” She arranged a time for them to come to the apartment to get it. And then she arranged to have two detectives hidden and waiting. As soon as Blanche paid $300 in marked bills to Alice, the officers pounced. On March 17, 1914, The Evening Telegram noted, “Mrs. Tovey said to-day that she loves her husband and intends to stand by him in this affair.”

Two months later, on May 8, the Borchardt received more unwanted publicity when 51-year-old resident Joseph Fleischman, the proprietor of Fleischman’s Baths on West 42nd Street, was arrested for assaulting a woman. That night Patrolman Turk heard a woman scream, then saw Mrs. Frank Lightfoot “run from the Fleischman building, her face bleeding and her hair disheveled,” as reported by The New York Press. She ran up to Turk and pleaded for him to protect her. Officer Turk took her into the baths, where she identified Fleischman as her attacker. The article said “In the station house the woman exhibited a lacerated left eye, which she said, was caused by Fleischman striking her. She refused to go into particulars.”

Guy Phillips was not only assistant secretary of the Missouri Pacific Railway Company, but held the same position with the St. Louis, Iron Mountain & Southern Railway Company; was secretary of the Iron Mountain Car Trust; president of the Opera House Realty Company; and held similar offices in several other concerns. Almost all wealthy New Yorkers had a country home, and his was in Darien, Connecticut. It was common for husbands to stay in town several days during the week to conduct business, and so on July 2, 1914, Phillips was at the office while his wife was in Darien. He was still working when the night watchman made his rounds at 9:00. When Edward Murphy returned an hour later, he found Phillips dead with a bullet wound in his right temple. He left a note asking for someone to call his wife and to notify his doctor.

Leonard Oppenheimer, a vice-president and director of Steiner & Son, was described by The Sun on April 8, 1925 as “a wealthy manufacturer.” On Sunday afternoon, April 5, he and his wife left the Borchardt at 3:00 “and motored until 6 o’clock, the servants having been dismissed for the afternoon,” according to the newspaper. When they returned home, they found that Mrs. Oppenheimer’s dresser had been opened, her jewelry boxes scattered around, and about $4,000 worth of jewelry was missing (a significant $61,800 in today’s money). It seemed to be an inside job, since entrance to the apartment had been made by using a key. The article mentioned, “None of the silver was taken, and Mr. Oppenheimer’s chiffonier had not been disturbed.”

A renovation completed in 1950 resulted in 9 to 12 apartments per floor. The building received a group of tenants in 1970 when Woodstock Community rented 31 apartments for 50 scholastics and priests who studied or taught at Woodstock College, the oldest seminary of the Society of Jesus in America. On December 28, 1971, The New York Times explained, “Students are on their own for breakfast and lunch, but every evening all 60 Jesuits in the building gather in an elegantly decorated dining room on the eighth floor for a buffet dinner catered by Schrafft’s.”

The building received a group of tenants in 1970 when Woodstock Community rented 31 apartments for 50 scholastics and priests who studied or taught at Woodstock College…

Not all of the Jesuits came and went without drawing attention. On August 23, 1971, The New York Times reported, “The Federal Bureau of Investigation foiled antiwar raids on Federal offices in Camden, N.J., and Buffalo over the weekend, arresting 25 people, including two Roman Catholic priests and a Lutheran minister.” Among the priests was Rev. Peter D. Fordi, who was also a member of the East Coast Conspiracy to Save Lives. Two weeks later, the newspaper reported that another Jesuit resident of the Borchardt, 36-year-old Rev. Edward J. McGow, had been indicted “in connection with the destruction of Selective Service files in Camden, N. J.” on the same day.

Resident Michel R. Colen (not one of the Jesuits) was also an activist. He was removed from the Senate Watergate hearings in Washington on August 7 and arrested. He and seven others had begun reading a statement accusing the CIA of “intervening in domestic political life.”

Thomas P. Sweetin was living here in 1977 when he was informed by the head of the New York Jesuit Province, “that he was being forced out of the order after 13 years of preparation for the priesthood.” The reason given was that “he was an admitted homosexual,” according to The New York Times on October 27. He had been asked for a year to voluntarily leave the order, which he refused to do.

Nine years later, Rev. John J. McNeill jeopardized his own standing in the church when the Vatican released a document on October 30, 1986, that reasserted the church’s teaching against homosexual activities. Defying a Vatican directive to remain publicly silent on the subject, McNeill issued a page-and-a-half statement to The New York Times and to the National Catholic Reporter condemning the Vatican’s announcement as “mean and cruel.”

By 1989 what was now known as the West Side Jesuit Community was renting just 16 apartments, which held 18 priests and one religious brother. Some of them had been in the building for two decades. That year the management of the Borchardt initiated an eviction action against them, charging that the Jesuits “constituted a monastery and therefore do not enjoy the right of regular tenants to renew their leases under the Rent Stabilization Law.” The Jesuits, like their landlord, hired an attorney. Rev. Daniel Berrigan, a “poet-priest,” told The New York Times, “It seems to me the quality of human life, and our efforts on behalf of people, is being subjugated to this lust for money…He can get more money than we’re offering.” The battle was still ongoing as late as 2005.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

BUILDING DATABASE

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business at 248 West 105th Street aka 2737 Broadway:

Meet Harmeet Singh!