The Hotel Belleclaire

by Tom Miller

In turn-of-the-century New York City the shops of silversmiths like Gorham and decorators like Louis Comfort Tiffany glistened with Art Nouveau accessories for the home. Sinuous vines and spilling wisteria blossoms formed vases and tableware and stained glass lamps. The fashionable home without an Art Nouveau hand mirror or hairbrush was rare.

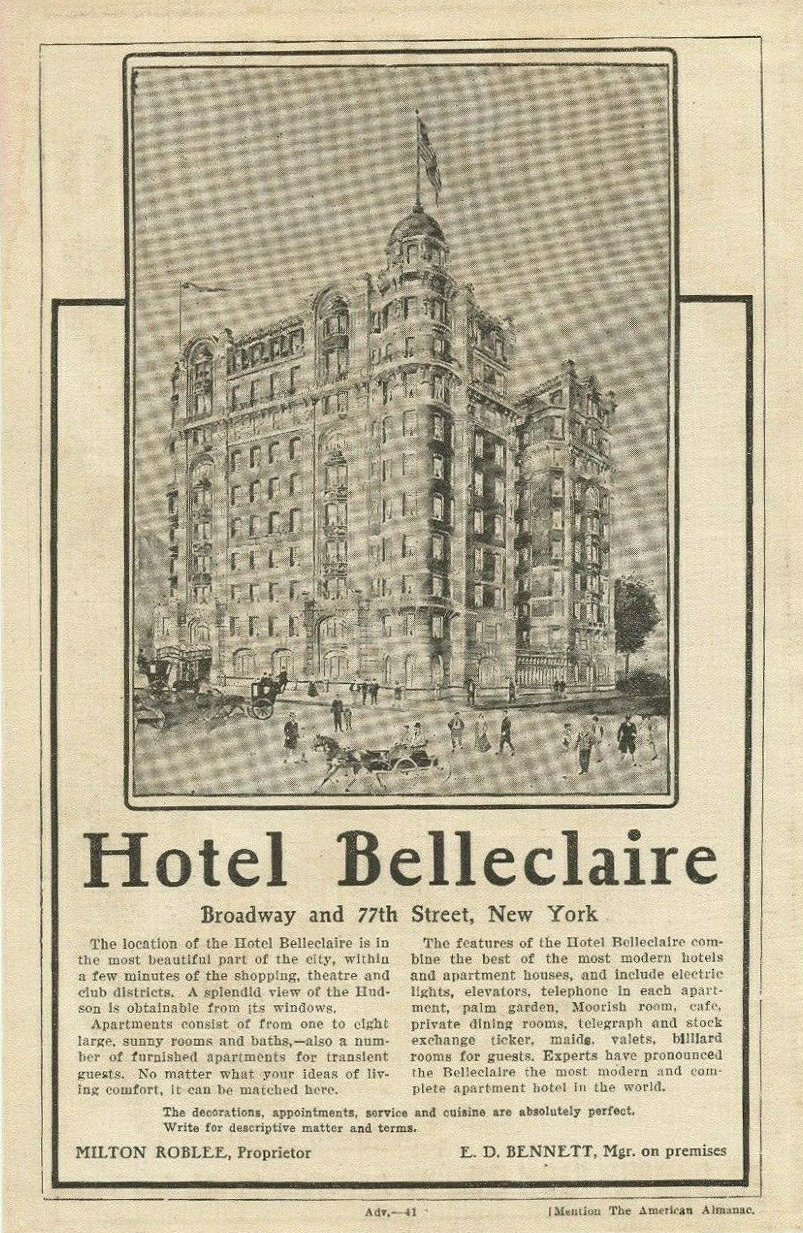

But the style never really caught on in New York architecture. For their staid American clients, architects tended to rely on the safer Beaux Arts or neo-Georgian styles, for instance. But Emery Roth was apparently unafraid. In 1902 his exuberant little two-story Art Nouveau hotel at 557 8th Avenue was completed. And then, a year later, came the grand Hotel Belleclaire—something like New York had never quite seen.

Located at Broadway and 77th Street, it was a residence hotel; designed for upper class families who preferred to avoid the bother of maintaining a private house. By 1903 the Upper West Side was nearly fully-developed with eccentric turreted and gargoyled mansions lining the avenues and streets. Already the elaborate Ansonia residence hotel had risen on Broadway (then called The Boulevard) between 73rd and 74th Streets. The Belleclaire would provide one more reason for moneyed New Yorkers to move west.

Construction had begun on the hotel in 1901. Owner Albert Saxe was familiar with Roth’s work, having hired him to design the Saxony Apartments a few years earlier. The commission for the Belleclaire was the architect’s first really substantial project and would be a career-changing one.

Although he splashed the building with some Beaux Arts details, Roth heavily relied on Art Nouveau and the related Viennese Succession styles. The windows of the first floor were recessed, with curved and flowing Art Nouveau mullions and twisting metal railings along the sidewalk that might have been more at home in Paris.

Long Viennese Seccession pendants, three stories tall, dangled from the 8th floor cornice. Here Roth incorporated an American motif – an Indian head – along with the very European detail. Stone arches, a corner tower and a deep courtyard on 77th Street added to the visual appeal.

Saxe intended to offer his tenants the latest in conveniences. On April 25, 1903 The Electrical World and Engineer noted that “contracts have been taken covering a complete long-distance telephone service for every room and working department in the hotel.”

Earlier, in January, Architect’s and Builder’s Magazine listed the amenities available to the Belleclaire’s residents. “The ground floor is devoted entirely to the hotel business, and has large and commodious offices, and a beautiful promenade hall extending the entire length, off from which you may enter the Louis XV ladies’ dining room, the Italian Renaissance palm room, the Flemish café, the Mission library and the Moorish private dining room.”

The New York Tribune recommended the hotel, calling it in 1905 “one of the finest hotels in the city, offering exceptional advantages and comforts. The roof garden is one of its most attractive features during the warm summer evenings.”

“Other space is devoted to flowers, cigars, news, telephone and telegraph offices, etc., two passenger elevators, freight elevator for baggage and servants, mail chutes, and in fact every modern up-to-date convenience.”

Although mainly a resident hotel, the Belleclaire also accepted some transient guests. Manager Milton Roblee, in an inventive marketing scheme, published a sleek magazine Hotel Belleclaire World for which Broadcast Weekly said he was “entitled to considerable credit for the attractive appearance of the publication.” Roblee gave no regular schedule for publication, explaining that “The Belleclaire World…will be issued just as often as the activities of civilization demand.”

The New York Tribune recommended the hotel, calling it in 1905 “one of the finest hotels in the city, offering exceptional advantages and comforts. The roof garden is one of its most attractive features during the warm summer evenings.”

Indeed Roblee hoped that very feature would deter his transient guests as well as residents from abandoning the hotel during the hot New York summers when the upper class traditionally fled to the sea side. In a 1905 he argued, “Why go to the country, put up with small narrow rooms, flies, mosquitoes, and a thousand and one little annoyances, when you can enjoy a metropolitan vacation at The Belleclaire and avoid them all…Many of the families now living in the hotel have signified their intention to remain, and a number of people from the South have apartments arranged for.

“The Belleclaire will be no ‘Lonesomehurst’ during the heated term. Lieut. Kessler and his exquisite orchestra will be retained. The roof garden will be so arranged that you may enjoy the cool breezes and delightful view, together with other forms of refreshment.”

That same year noted artists were living here like the opera soprano Bessie Abott and well-known actor E. J. Morgan. The English-born Morgan was most known for his work in epic Biblical plays such as “Ben-Hur,” “The Christian,” “Quo Vadis,” and “The Eternal City.” When his wife found his body in their apartment on March 10, 1906 his death was assumed to be a result of his bad heart.

It was, rather, a freak accident no one could have imagined. Two days later The New York Times reported that “in the opinion of Coroner Shraby and Coroner’s Physician Weston, his death was caused by asphyxiation following a fall which pinioned his head between a steam radiator and the carpet.”

A month later an international incident would focus attention on the Hotel Belleclaire. When Russian author and Socialist activist Maxim Gorky arrived in Hoboken on the ship Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse on April 10, he was received with overwhelming warmth. The New York Times reported that “the reception given to Gorky rivaled with that of Kossuth and Garibaldi.”

Gorky related that now his long-cherished dream to visit the free land of America had come true. It was a love affair that would be short-lived.

Wealthy tenant H. Gaylord Wilshire arranged rooms for Gorky and “Madame Gorky” in the Belleclaire. On April 13 more than a hundred reporters and members of various organizations attended a reception his Gorky’s suite where the stylish Madame Gorky was also present.

The following day, however, The World printed a photograph of the woman with the caption “[the] so-called Mme Gorky who is not Mme Gorky at all, but a Russian actress Andreeve, with whom he has been living since his separation from his wife a few years ago.”

It was a scandal Milton Roblee was not willing to abide. He forced the couple to leave The Belleclaire.

“My hotel,” he told The New York Times, “is a family hotel, and in justice to my other guests I cannot possibly tolerate the presence of any persons whose characters are questioned in the slightest manner.”

The newspaper added, “Mr. Wilshire then hastened to the hotel and pleaded with Mr. Roblee to relent, but to no purpose. He told Mr. Wilshire that he had not been anxious to have the Russian author in his hotel in the first place, and certainly would never have admitted him had the slightest hint of the circumstances since printed reached him before they arrived.”

Gorky and his mistress left, but he told reporters, “The publication of such a libel is a dishonor to the American press. I am surprised that in a country framed for its love of fair play and reverence for women such a slander as this should have gained credence.”

The incident did not deter upper-class New Yorkers from settling in the Belleclaire. Dentist James Goodwillie, who had, according to The Dental Cosmos magazine, “an extensive and high-class clientele,” lived here until his death in 1907. Goodwillie was responsible for the invention of “a number of useful improvements in dental appliances,” said the magazine.

Tragedy struck the hotel that same year. John Whitley was the senior member of J. Whitley & Co, a large steam fitting firm. In 1900 Whitley’s wife died and the 53-year old shocked his children when he almost immediately married his beautiful and much younger nurse.

The New York Times later reported “His young wife desired to live well, and he granted her everything she asked. She had an abundance of jewels and dresses.” That came to an end on Thanksgiving morning 1907 when Whitley got out of bed around 2:30 in the morning, placed a pistol to the head of his sleeping wife and fired twice.

The millionaire then flung himself from his ninth-floor apartment window to the sidewalk.

In 1908 the hotel was the first in New York City to have its own fleet of taxicabs and in the ensuing years it would be home to business executives like Stephan A. McMahon, an officer of The Stepucy Spare Wheel Agency that manufactured “motor wheels;” Alfred and Helen Bishop, owners of Bishops Manufacturing company; Dr. Frank L. Pia, and Louis Stern, president of the Broadway wholesale dry goods firm of Stern Trading Company.

In 1900 Whitley’s wife died and the 53-year old shocked his children when he almost immediately married his beautiful and much younger nurse.

When Captain S. C. Fean resigned from active sea duty, The Oil Trade Journal remarked in 1918 that he “is luxuriating at the Belleclaire hotel in New York.”

Two year later the guests at the hotel were victims of an outlandish marketing scheme by press agent Harry Reichenbach. In a bizarre attempt to promote the motion picture “The Return of Tarzan,” he secretly released a lion in the halls of the hotel and left; leaving the management to figure out how to capture the animal and dispose of it.

Numa Pictures Corporation’s vice-president, Louis Weiss, released a press statement shortly afterwards nonchalantly noting that “I wish to emphasize the fact that Jimmie, the principal lion in the S & E state rights offering, “It Might Happen to You,” is the same lion who was recently registered at the Belleclaire Hotel in New York.”

In 1925 architect Louis Allen Abramson was commissioned to do a $100,000 renovation of the ground floor. Roth’s wonderful Art Nouveau windows and outside railing were removed, replaced with storefronts along Broadway. The entrance to the hotel was moved to the 77th Street courtyard.

That same year the hotel’s president Walter Guzzardi put his foot down. He announced, said The Times on March 4 that “there would be no more high school fraternity dances at the hotel. This decision had been reached, he said, because there had been more drinking than dancing at many of the student organization ‘hops.’”

When management found 25 empty liquor bottles on the ballroom floor at the last party, police were called in to end it. Then, “windows were opened to freeze out the celebrators when they refused to leave.”

By mid-century the hotel was in major decline and around then lost the dome to its corner tower.

As the 1980s arrived the grandeur and elegance of the early decades were gone. In 1981 a rookie policeman and his partner entered the derelict hotel to find three people shot to death. One was a twelve-year-old girl shot three times in the head. Paul Stoller in his “Money has No Smell” described the hotel as it was in 1991. “It has ten floors of gloomy hallways, all of which smell of mildew and stale sweat.”

By the time struggling musician James Morrison lived there in 2000, it was a welfare hotel. Guests were allowed to stay no more than one month at a time. So Morrison and his musician would sleep in a movie theater for a night before re-registering.

In his “Blowing My Own Trumpet,” Morrison wrote “On the second floor it looked like there was an informal brothel operating; on the third floor there were a few guys who looked like they were handling a major drug distribution centre or running guns (or both).”

Then, in 2008, the hotel was renovated and upgraded into an affordable neighborhood hotel. The 240 rooms continued to be one-by-one refurbished in 2011 with modern amenities like WiFi and a new exercise room was installed.

Despite half a century of misuse, Emery Roth’s turn-of-the-century hotel survives as one of the rare examples of Art Nouveau architecture in New York.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

Building Database

Landmarks Timeline

Keep Exploring

Designation Report

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the business currently at 2175 Broadway:

Meet Amer Ait Ouhamou and Steven Kelly!