The Manhattan Towers Hotel

by Tom Miller

The burgeoning population of Upper West Side desperately needed churches, police stations and fire houses by the mid-1890’s. In June 1896 a meeting was held in Leslie Hall, on 83rd Street and Broadway, which resulted in the formation of the Manhattan Congregational Church. In November it was organized with 110 members. The religious-themed magazine The Treasury noted in April 1902 “Three years later, or in January, 1900, the church purchased eighty feet of land on Broadway near the corner of 76th Street, 134 feet deep with an L extending through to 76th Street.” The congregation had chosen its site wisely. The article continued, “This property has proved to be very valuable. It is in the centre [sic] of a dense population and on the main artery.”

The architectural firm of Soughton & Soughton was commissioned to design what would be an highly-unusual ecclesiastical structure. Foregoing the expected Gothic Revival, the architects created what they termed a “Louis XIII Gothic” building. There were few pointed arches, no bell tower, and instead of a steeple, the church sprouted an over-sized fleche.

Broadway had become a bustling, commercial thoroughfare by the mid-1920’s. A new concept in church design and finances, first seen on the West Coast, was catching on in America’s largest cities–the “skyscraper church.” Vintage church buildings were being demolished to be replaced by hotels or apartment buildings which retained space for the church. The congregations therefore reaped rental income from the residential and commercial spaces. Not everyone warmed to the idea. In 1926, after several such skyscraper churches had appeared in Manhattan, The New York Times lamented “Must we visualize a New York in which no spire points heavenward?”

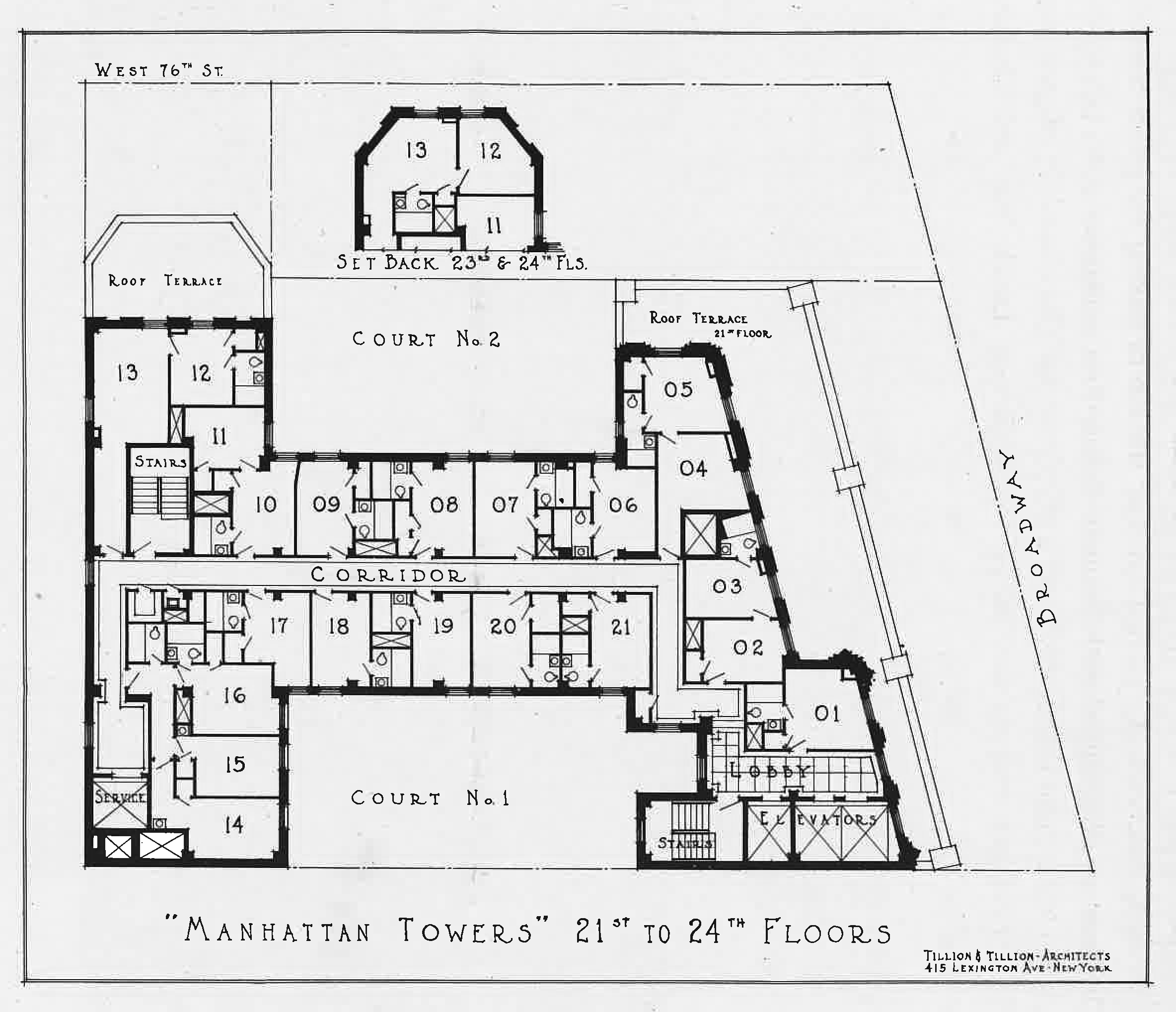

To deal with the heavily changed personality of its location, the Manhattan Congregational Church joined the trend. In 1927 pastor Rev. Edward H. Emmett announced that the 1901 building would be razed and replaced by a hotel. Architects Tillion & Tillion were put to work designing a 24-story structure.

Before the first brick was laid The Manhattan Congregational Church leased the hotel and commercial portions to the 2168 Broadway Corporation. Strict covenants were written into the lease, including the incorporation of certain elements of the old building into the new. To be removed and reinstalled were the “gates, cornerstone, leaded windows, wood-work, mantels, medallions, figures from the Church spire, chandeliers, signs, organ, pews, choir stalls, seats, cushions, carpets and other furniture.” In short, the old church was essentially being reproduced within the hotel building. Another restriction was that the shops at street level could be rented only to businesses which closed on Sundays.

Demolition began in May 1928 and the 23-story Manhattan Towers Hotel was completed two years later. Construction had cost $2.1 million–about $31.6 million today. Timing could not have been worse since the Stock Market had crashed just months earlier.

Five lower floors were dedicated to church use. The auditorium accommodated 800 worshipers and there was a gymnasium, Sunday School rooms, offices and meeting rooms. The Manhattan Towers Hotel held 626 rooms plus two penthouse apartments.

While Tillion & Tillion designed the brown brick upper stories of the hotel in an understated Art Deco style, the stone-clad base reflected the church inside with traditional Gothic Revival.

Despite the best intentions of the Manhattan Congregational Church the Manhattan Towers Hotel was from the beginning a nest of scandal, crime and tragedy, and a favorite haunt of gangsters.

On December 17, 1931, for instance, The New York Sun reported on the arrests of tenant Charles Smilowe on charges of swindling. He offered customers expensive goods and delivered cheap initiations instead. He was nabbed after he charged a wary John Fluckiger $1,200 for five oriental rugs. Fluckiger arranged for a detective to accompany him to Broadway and 70th Street where a taxicab was to drop off the rugs. The Sun reported “When it arrived it was found to contain a large package and a boy who said a man had given him $2 to deliver the package and receive an envelope.” The detective and Fluckiger climbed in the cab and the boy took them to Smilowe.

In 1926, after several such skyscraper churches had appeared in Manhattan, The New York Times lamented “Must we visualize a New York in which no spire points heavenward?”

Two suicides were connected with the hotel that year. The Depression had dealt a hard blow to Albert E. Oberfelder’s chiffon business. The 50-year old checked into the hotel in October and hanged himself from a closet door. He left a note saying that he was driven to kill himself by “business losses.”

Two months later Broadway dancer Jack Thompson committed suicide. He had had a successful career on stage, but in 1930 tore a tendon. It appeared now that he would never dance again. He threw a party on November 3 in his room in the Manhattan Towers. Late in the night he told his guests he was going to throw himself into the river. His friend kidded him, saying the water was too cold this time of year, never presuming he was serious. The body of the 32-year old was not identified until December 13.

In the meantime, the Manhattan Congregational Church had other problems. The hotel floundered and could not meet its $20,000 per year rent. In turn the church was unable to pay its annual $25,000 mortgage payment. On October 5, 1931 the Bank of Manhattan Trust Company began foreclosure proceedings.

While the bank and the church negotiated, the hotel continued to be the scene of trouble. Federal Prohibition agent, Sebastian J. LaScola rented a room here in the spring of 1932. At around 2 a.m. on March 24 he was awakened to knocking at his door. When he opened it he was rushed by two thugs. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that they “tied him down to his bed and helped themselves to what they could find.” And what they found was $65 in cash, two gold watches, his agent’s badge, a blackjack, a .38-caliber revolver and .45-caliber automatic pistol.

Unfortunately for the crooks, they were too obvious in their exit from the building and into a waiting car. Two cops, Matthew White and Harry Mullett “thought there was something suspicious in the swift departure and pursued them in a police car.” The thieves were arrested a block away.

The following spring another tenant, 32-year-old Simon Haines was arrested for swindling downtown businessmen. He was picked out of a line-up, on April 11, but, according to The New York Sun, “refused to answer questions.”

No petty swindler was notorious gangster Joseph “Spot” Leahy who lived here at the time. He had been known to police since he was involved in the West Side Gopher Gang as a youth. Since 1916 he had been arrested 21 times and was a suspect in a dozen murders. Twice he had escaped from jail.

On October 1, 1933 he headed up the staircase to the second-floor speakeasy, the Tonawanda Social Club, nearby at No. 2744 Broadway. He never came out. He was caught off guard in the dark staircase and his throat slit. When police searched the body, according to The New York Times, they found “a key to a $12-a-week room at the Manhattan Towers Hotel, 2,166 Broadway, where he was registered under the name of J. S. Boyer.”

The patience of bank officials ran out that year. Two days before Christmas the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported “Failure to make good on its bonds has resulted in the Manhattan Congregational Church…foregoing its Christmas service. The church was sold at auction to the Commonwealth Bond Corporation for $200,000 by the Bank of Manhattan Trust Company.” The new owners locked the church doors. Before long they leased the sanctuary to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day-Saints, commonly called the Mormons.

New ownership did not improve the reputation of the hotel, which continued to house criminals and be the scene of suicides.

Like Albert E. Oberfelder, the Depression ruined 40-year-old Martin E. Reis. In March 1934 he closed his office at No. 220 Fifth Avenue for good, and on the 5th of that month rented a room on the 18th floor of the Manhattan Towers. On June 12 he opened his window and jumped.

An employee noticed an open hall window on the top floor on April 4, 1938. Leaning out he saw the body of Reginald West on the roof of the 76th Street garage next door. West did not live in the hotel, but came here only to end his life.

The pattern continued the following year. Desk clerk William Radd answered the phone just before 10 a.m. on May 13, 1939. A tenant, 60-year old retired dress salesman Cyril Hart, said “I’m sorry for what I’m going to do. I’m going to jump out of the window. I don’t see any way out and I left some notes for my friends.” Before Hart could rush upstairs to stop him, Hart had plunged to his death.

The Commonwealth Bond Corporation was unable to keep up with taxes and in 1943 the building was taken by the City. It was sold at auction on December 30 to Detroit-based hotelier Isadore Kowal.

With the United States now embroiled in World War II, the owner devised an inventive way to use the property. On the same day of the sale, according to the Oswego Palladium-Times, “The Navy is seriously considering the leasing of the Manhattan Towers Hotel, 2166 Broadway, near Seventy-sixth street, for Waves on duty in the metropolitan area.”

Just over four months later, on May 1, 1944 the same newspaper reported “The WAVES today took over the 24-story Manhattan Towers hotel…as a barracks receiving station.” The barracks would accommodate 950 female sailors. The sleeping rooms (which had been “washed and painted in light blue, light yellow, peach and ivory”) were shared by two women each, who slept in bunk beds. The Waves were permitted to choose their roommates.

The conversion did away with the church space, forcing the Church of Latter-Day Saints to find new accommodations. The renovated hotel now included two lounges, an auditorium, a gymnasium and a library.

Military duty did not prevent the Waves from finding romance in the big city. One of the love-struck women was 23-year-old Evelyn Zita Reppucci. In January 1945 she met a handsome six-foot, two-inch tall Marine, Howard Geier. His uniform was adorned with not only two stars, an American Defense Medal and an Asiatic-Pacific campaign ribbon, but a Purple Heart.

Evelyn listened to his stories of service from Guadalcanal to Saipan. The New York Sun said they “had a whirlwind courtship, with the soft whispers of love interspersed here and there by tales of heroism.” Only a month later, on February 13, later Geier obtained a marriage license at City Hall. He then waited for his fiancée in front of Wave headquarters at No. 90 Church Street. But the wartime romance was about to come to an abrupt end.

The uniform and the impressive decorations on the youthful-looking Geier raised suspicions of Navy shore patrol officers. They detained him while his background was checked. It turned out that the would-be Marine was just 16-years old and lived in Brooklyn. He had obtained the marriage license by saying he was 24 and used the name Howard Leblane.

The uniform was gone when Geier appeared in court a month later. Nevertheless, The New York Sun described him as “handsomer than many a movie star.” A humiliated Evelyn admitted she had fallen for his story, saying “he sure had a wonderful line,” but she was “all washed up now.” Magistrate Ramsgate decried the prisoner as “a Broadway commando.” Nevertheless, because of his age, he was discharged. His attorney said he was waiting for his 17th birthday so he could join the Marine Corps for real.

As that drama was playing out in court another romance had a happier ending. Yeoman Third Class Luella Crosble was married to Navy Fireman First Class Ronald Rhude in the chapel of the U. S. Naval Barracks, on March 6. The Post-Star of Glens Falls, New York, noted that it was “the first formal wedding performed there since the Navy took over Manhattan Towers as Waves’ quarters.”

On April 11 [1980] The New York Times reported that the 530-room Opera Hotel would be converted into 113 cooperative apartments. The article noted that “it acquired notoriety as a crime center in the early 1970’s.”

Following the war, the Manhattan Towers was once again a hotel. It was the scene of chaos and panic on February 1, 1970 following an explosion of leaking gas in the basement. The Bellevue Hospital Disaster Unit rushed to the scene where about 50 persons were injured. The police sped 15 injured firefighters to hospitals in police cars.

By now the Manhattan Towers was being run as a single-room-occupancy hotel and was a hotbed of criminal activity. On December 6, 1972 Deputy Mayor Edward K. Hamilton announced the city’s plans to start evening and late-night inspections of similar facilities. He mentioned the Manhattan Towers, saying that security was “inadequate, since too many people had free access to the hotel and the attitude of the tenants toward management was negative.”

A month earlier Sgt. Joseph A. Burns of the 20th Precinct told reporters that “15 per cent of all robberies in the precinct take place in the Manhattan Towers Hotel.” At the time the city housed 186 welfare recipients there.

Things did not improve. On November 15, 1974 police reported that two Upper West Side hotels, the Manhattan Towers and the West Side Towers had accounted for 207 crimes in the first nine and a half months of the year. “That figure includes only crimes occurring on the premises,” explained The New York Times. “Unreported crimes in the buildings and crimes committed by the hotels tenants in the neighborhood would swell the totals.”

Almost unbelievably, given the sordid state of the hotel above, the basement level was converted to a children’s theater in 1969. In the Promenade Theater the Meri Mini Players staged plays like Pinocchio for juvenile audiences and their parents for years.

Meanwhile, the situation in the hotel only worsened. In 1976 two men, 21-year old Hector Senidy lived in a room here (now known as the Opera Hotel). In June he and an accomplice, Slavio Golletta, kidnapped and beat a young man, John Boeggeman, whom they held in Golletta’s room in the Capitol Hotel on West 87th Street.

The thugs demanded $10,000 ransom from Boeggeman’s father. Undercover detectives were watching as he handed over an envelope of $100 bills. Fifteen minutes later they followed Golletta and Senidy to Room 407 of the Capitol Hotel where they found Boeggeman bound to a chair and bleeding from the face. Both men were charged with kidnapping and grand larceny by extortion.

Two years later gangster Harold “Whitey” Whitehead was found murdered in the basement of the hotel. He had called a member of another gang a “rat.” When Whitehead walked into the basement room, that member’s brother retaliated by shooting him dead. His body was left on the basement floor to be discovered later.

One of the storefronts (ironically, which the Manhattan Metropolitan Church had insisted be closed on Sundays in 1930) was now home to the Plaka Bar. On November 22, 1978 two men walked up to the bar and shot the bartender, Harold Whitehead, point blank in the head. One of the slayers, Francis T. Featherstone, had earlier been accused of murdering Michael J. Spillane. The New York Times said Spillane “has been described as a rival of Mr. Featherstone’s for the leadership of the mob.”

Salvatore Giannini lived in the hotel in 1980 when the 24-year-old was convicted of robbery. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to between three to nine years in state prison. His would be the last of the unsavory goings-on in the Opera Hotel.

On April 11 that year The New York Times reported that the 530-room Opera Hotel would be converted into 113 cooperative apartments. The article noted that “it acquired notoriety as a crime center in the early 1970’s.” Now, developer Lewis Futterman, who paid $1.8 million for the property, hired architect Bernard Rothzeid to transform it. The apartments would range from one- to three-bedroom units.

The renovations were completed in 1983. Although the real estate brochure got the building’s history woefully wrong (“Originally built in 1929 by the Mormon Church as both a home and place of worship for many of its local adherents”), it was correct in saying “Now the Upper West Side is in the midst of a renaissance.” There was a commercial gym in the basement and the theater space now engulfed three floors. The theater became home to Second Stage in 1982.

Tom Miller is a social historian and blogger at daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com

building database

Keep Exploring

Be a part of history!

Think Local First to support the businesses and nonprofits currently at 2162 Broadway

Learn about ReUse of the Manhattan Congregational Church!